William of Tyre on Byzantium & Manuel Komnenos - A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea

William of Tyre knew Manuel very well over a number of years. He strayed with him for seven months in Constantinople before heading for western Europe. Manuel spoke French (and probably Turkish) so here was no language barrier. I don't know if William spoke Greek or not. Some of his fellow Latin clerics in the Latin Kingdom did. His history was written in Latin.

William of Tyre knew Manuel very well over a number of years. He strayed with him for seven months in Constantinople before heading for western Europe. Manuel spoke French (and probably Turkish) so here was no language barrier. I don't know if William spoke Greek or not. Some of his fellow Latin clerics in the Latin Kingdom did. His history was written in Latin.

Manuel's second wife was a French princess from Antioch. They had one son who was betrothed to the daughter of King Louis VII of France and Eleanor of Aquitaine, who moved to Constantinople. Louis and Eleanor had visited Constantinople and had been guests of Manuel. Many of Manuel's best friends were "Latins". There were a large number of them in Imperial service and fighting as mercenaries in the army. I have gone through all of this book and have selected the most important parts related to Manuel to put here. I have put lines between the sections.

The part related to the death of John II is very interesting. It is believed that John was assassinated by his French mercenaries by poisoning and this story is not truthful. His father had intended for Manuel to become king of a new eastern kingdom he would create. That's one reason Manuel learned French at a young age. His father took him with him on all of his campaigns and introduced him to all of the rulers of cities and realms of the east they visited. John's plans were ruined when Manuel's two other brothers died within a few days of each other. The first, Alexios had been crowned co-emperor and was married to a Russian princess. His younger brother, Andronikos, was also married to a Russian. John and his wife, Eirene-Piroska, a Hungarian princess of French descent, had eight children. After Alexios and Andronikos died John passed over the next son, Isaac and gave the throne to Manuel. Isaac was a problem son for John. He was not interested in the army and was an intellectual. I also think John felt he could not be trusted and lacked the values an emperor had to process to rule effectively.

William's account of the terrible defeat of Myrokhephalon in 1176 is very personal, it's obvious that he was in Manuel's inner circle and observed his reaction first-hand.

William was Archbishop of Tyre from 1175-84 and an official from 1174 until his death of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, He was born in the Crusader Kingdom in 1130 and died in 1186 when he was around 55 years of age. - Bob Atchison

About this time, Alexius, emperor of Constantinople, the worst persecutor of the Latins, was removed from the affairs of this world, He was succeeded by his son John. This emperor was much more humane than his father had been, and, as his worth deserved, was far more acceptable to our people. His attitude toward the Latins was not entirely sincere, however, as the following pages will show...

Meanwhile numerous reports began to circulate through the land. It was rumored that John, emperor of Constantinople, son of Alexius, was about to descend swiftly upon Syria. From every part of his empire he had summoned people of all tribes and tongues, and now, with a countless number of cavalry and a vast array of chariots and four-wheeled carts, he was on the march. Nor was this mere empty rumor. As soon as he learned from reliable sources that the people of Antioch had summoned Raymond thither, that they had given the city to him, and had bestowed upon him as his wife the daughter of Lord Bohemond, John determined to go to Antioch. Very wroth was he that, without his knowledge or command, they had presumed to give the daughter of their lord in marriage and, without consulting him, had dared to hand over the city to the rule of another. He claimed Antioch with all the adjacent provinces as his own and wished to recall them to his own jurisdiction. He asserted that those great princes, men of valor and immortal memory who, at the command of God, had come on the first expedition (time does not permit the mention of their names one by one), had entered into a definite agreement with Alexius, his father and predecessor in the empire, with much inter- change of gifts and courtesy. The terms were that whatever cities or fortresses the Christians might by any chance take on that campaign should be surrendered without contest to the empire. These, when captured, they had undertaken to guard faithfully to the best of their ability and strength until he should come with his army. These provisions, John asserted, were included in the pact, and the princes had confirmed them with solemn oath.

Meanwhile numerous reports began to circulate through the land. It was rumored that John, emperor of Constantinople, son of Alexius, was about to descend swiftly upon Syria. From every part of his empire he had summoned people of all tribes and tongues, and now, with a countless number of cavalry and a vast array of chariots and four-wheeled carts, he was on the march. Nor was this mere empty rumor. As soon as he learned from reliable sources that the people of Antioch had summoned Raymond thither, that they had given the city to him, and had bestowed upon him as his wife the daughter of Lord Bohemond, John determined to go to Antioch. Very wroth was he that, without his knowledge or command, they had presumed to give the daughter of their lord in marriage and, without consulting him, had dared to hand over the city to the rule of another. He claimed Antioch with all the adjacent provinces as his own and wished to recall them to his own jurisdiction. He asserted that those great princes, men of valor and immortal memory who, at the command of God, had come on the first expedition (time does not permit the mention of their names one by one), had entered into a definite agreement with Alexius, his father and predecessor in the empire, with much inter- change of gifts and courtesy. The terms were that whatever cities or fortresses the Christians might by any chance take on that campaign should be surrendered without contest to the empire. These, when captured, they had undertaken to guard faithfully to the best of their ability and strength until he should come with his army. These provisions, John asserted, were included in the pact, and the princes had confirmed them with solemn oath.

There is no question that these princes had concluded an agreement with the emperor and that he, in turn, had bound himself to them by definite pledges which he had been the first to break. Since he had not kept to the terms of the agreement, the signatory princes steadfastly maintained that they were not bound to him. No less did they regard those who had already died as released from their agreement, since Alexius, as a vacillating and unstable man, had dealt fraudulently with them and had been the first to break his own pledges. According to the law of treaties, therefore, they rightly claimed that they were released from the pact, "For to keep faith with one who tries to act contrary to the tenor of a treaty is wrong."

Accordingly, the emperor sent officers throughout all his empire, and an entire year was spent in making the necessary preparations for a campaign, as befitted imperial magnificence. Then, followed by chariots and horses, an innumerable host, and accompanied by treasures of inestimable weight, number, and measure, he sailed across the Hellespont, which in common parlance is called the arm of St. George, and took the road toward Antioch. After crossing the intervening provinces, he came into Cilicia and halted to besiege Tarsus, a famous city of Cilicia Prima. This he took by force of arms, cast out the loyal subjects of the lord of Antioch, to whose faithful care it had been entrusted, and put in his own nobles. Without delay, in like fashion, he made himself master of Adana, Mamistra, and Anavarza, the most populous city of Cilicia Secunda. He also took the other cities of that province, together with all the fortified towns and castles. Thus, contrary to all justice and right, he seized as a part of his own kingdom the entire province of Cilicia, which the prince of Antioch had held in undisputed possession for forty years. For even before Antioch had come under our power Tarsus had been restored to Christian liberty by Baldwin, the duke's brother, and Mamistra with all the rest of that region had been freed by the distinguished Tancred. Thence advancing in mighty strength, he pressed on to Antioch with all his armies. Upon his arrival there, he immediately began siege operations. Mighty machines and engines were placed in strategic positions around the city and ever-increasing pressure was exerted upon the place.

About this time, John, emperor of Constantinople, once more recruited his forces, summoned his legions, and again directed his campaign and his armies toward Syria. Scarcely four years had elapsed since he had left Tarsus of Cilicia and all Syria, but urgent messages, oft repeated, from the prince and the people of Antioch induced him to set forth. In the greatness of his might, with horses and chariots, with untold treasure and innumerable forces, he started for the land of Antioch.

Sailing across the Bosphorus, which is the well-known boundary between Europe and Asia, he crossed the intervening provinces and arrived at Attalia, the metropolis of Pamphilia, a large city on the seacoast. While he was lingering at that place, two of his sons, Alexius, the first born, and Andronicus, his second son, fell sick of a serious illness which ended with their death. The emperor at once called to him his third son, Isaac, and sent him back to Constantinople with the bodies of his brothers so that, as humanity requires, he might cause the last reverence to be shown to the remains and commit them to the tomb as befitted imperial majesty. When the funeral rites were over, Isaac continued, by his father's commands, to live in Constantinople until the death of the emperor.

The monarch then took his youngest son, Manuel, with him and continued his journey through Isauria into Cilicia. This country he traversed with great speed. Scarcely had the report of his advance been received before he marched with all his troops into the land of the count of Edessa and encamped without warning before TurbesseL..

The emperor of Constantinople dearly loved to hunt in the woods and glades. In the early spring, before the season when kings ordinarily lead forth their armies to war, he went to the forest attended by his usual escort assigned for the purpose. It was a custom of long standing which served to while away the monotonous hours. With bow in hand and quiver heavy with arrows as usual, he was pursuing the wild beasts with his customary energy. Suddenly a wild boar which had been started up by the dogs, infuriated by their shrill insistent barking, rushed past the hiding place of the emperor. With marvellous swiftness he seized an arrow, but he carelessly stretched the bow too far and wounded himself in the bow hand with the point of the poisoned arrow. Thus, from so trivial a cause, he received the summons of death. The pain of the wound soon compelled him to leave the woods and return to the camp. Physicians were summoned in numbers. He explained the accident to them and did not hesitate to say that he had caused his own death. Full of solicitude for their lord's safety, they indeed plain that without a leader the legions could not pass through, the intervening country in safety, for it was filled with enemies who would lay ambushes and summon assistance from all the country round about.

There was among the other great men of the court an illustrious prince, by name John the protosebastos. He, with those of his party, earnestly tried to secure the succession for Isaac and strove to reassure the emperor in his anxiety about the safe return of the troops. Manuel, the younger son, however, who was present on the campaign with his father, stood high in the estimation and favor of the entire army, particularly with the Latins. Some of the princes also worked diligently in every way for his interests. His father also regarded him with more affection and inclined toward him more favorably because he seemed wiser, more valiant in arms, and more affable in every way. Moreover, the responsibility of conducting the army back in safety weighed more heavily upon him.

After long deliberation, by the will of God the choice finally fell upon the younger son. Accordingly, at the command of the emperor and in his presence, imperial reverence was shown to Manuel. Then, as is the custom of that empire, he was clad in the purple hose and enthusiastically hailed as Augustus by the legions.

After Manuel had been thus raised to the supreme place of power in the empire, his distinguished father of famous memory, generous and pious, kind and merciful, yielded to fate. John was a man of medium height, with black hair and swarthy skin, and for this reason is still called the Moor. Though insignificant in appearance, he was distinguished for his lofty character and famous for his prowess in war. He died in a place called the meadow of Mantles, near Anavarza, a very ancient city, and the metropolis of Cilicia Secunda. His death occurred in the month of April, in the year of the Incarnation of the Lord 1143, which was the twenty-seventh year of his reign and of his life the . . . .

When the new emperor finally settled his affairs in that land, he led his armies back to Constantinople in safety. There he found that his elder brother, on the news of his father's death, had at once taken possession of the palace. Manuel therefore sent a private letter to the official who was in charge of the palace and all the treasures and ordered that his brother, who apprehended nothing of the kind, be seized at once and thrown into prison.

Later, however, after he had made his solemn entry into the city, he became reconciled to his brother through the friendly offices of kinsmen of both and of some of the nobles of the sacred palace. Thus, peacefully, Manuel obtained possession of the empire, according to the last wish of his father. As long as he lived, however, he never ceased to heap honors upon his brother as the elder and to show him abundant favor....

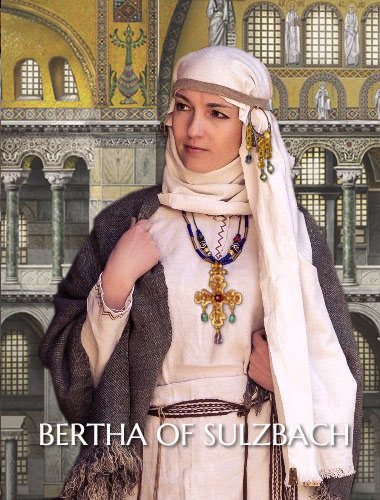

At Ephesus, the emperor (Conrad) commanded the legions which had survived to march back overland. He himself took ship and returned to Constantinople. The reasons for this action are unknown perchance he was chagrined over the depleted numbers of the great host which he had led forth - perchance he found the arrogance of the Franks unendurable. He was received by the emperor with even more marked distinction than before and remained at Constantinople with his nobles until the beginning of the following spring. The two sovereigns were closely united by marriage for their wives were sisters, daughters of the elder Berengar, count of Sulzbach, a great and noble prince, very powerful in the kingdom of the Teutons. Hence the emperor showed Conrad very great favor and, at the special request of the empress, lavished gifts upon him and his nobles most liberally.

At Ephesus, the emperor (Conrad) commanded the legions which had survived to march back overland. He himself took ship and returned to Constantinople. The reasons for this action are unknown perchance he was chagrined over the depleted numbers of the great host which he had led forth - perchance he found the arrogance of the Franks unendurable. He was received by the emperor with even more marked distinction than before and remained at Constantinople with his nobles until the beginning of the following spring. The two sovereigns were closely united by marriage for their wives were sisters, daughters of the elder Berengar, count of Sulzbach, a great and noble prince, very powerful in the kingdom of the Teutons. Hence the emperor showed Conrad very great favor and, at the special request of the empress, lavished gifts upon him and his nobles most liberally.

The surviving envoys, namely, Humphrey the constable, Joscelin Pisellus, and William de Barris, noble and illustrious men, well versed in secular affairs, pursued with due diligence the task entrusted to them (arranging an Imperial bride) at the court of the emperor. After numberless delays and equivocal answers expressed in mystifying circumlocutions such as the subtle Greeks delight in and usually employ, their request was gratified. Arrangements concerning the dowry and the donation for the marriage having been concluded, an illustrious maiden, a princess who had been reared in the strictest seclusion of the imperial palace, was named as the king's bride. She was in fact a niece of the emperor, the daughter of his elder brother Isaac, and was called Theodora. She was in her thirteenth year, a maiden of unusual beauty, both of form and feature whose entire appearance favorably impressed all who saw her. Her dowry consisted of a hundred thousand hyperperes, of standard weight, and in addition ten thousand of the same coins, which the emperor generously granted for her marriage expenses. The bridal outfit of the maiden, in gold and gems, garments and pearls, tapestries and silken stuffs, as well as precious vessels, might by a just estimate be valued at an additional fourteen thousand hyperperes.

About this same time also Manuel, emperor of Constantinople, of illustrious memory and loving remembrance in Christ, whose favors and most liberal munificence nearly everyone had experienced, met with a serious disaster in Iconium. With praiseworthy piety he was endeavoring to extend the Christian name by fighting against the monstrous race of the Turks and their wicked leader, the sultan of Iconium. But, because of our sins, he suffered there a great massacre. This involved not only his own personal following but also the imperial forces which he was leading with him in numbers so vast as almost to exceed human imagination. This engagement was attended by an enormous loss of men, among whom were some illustrious kinsmen of his own, well-worthy of special mention. In the number was his nephew, John the protosebastos, his brother's son, a man of distinguished liberality and noteworthy munificence, whose daughter King Amaury had married. While making a vigorous resistance against the foe, he fell, pierced by many wounds. The emperor himself succeeded in rallying most of his army and reached his own land, safe in body but almost overwhelmed in mind by the unfortunate disaster. This tragedy is said to have been due rather to the imprudence of the imperial officers in charge of the battalions than to the strength of the foe. For, although there were broad and open roads well adapted for the passage of the army and for transporting the mass of baggage and impedimenta of all kinds, which is said to have been beyond estimating, they incautiously entrusted themselves head-long to dangerous narrow places which had been already seized by the enemy. Under such circumstances it was impossible to offer resistance, nor was there any opportunity to turn the tables against the enemy. From that day the emperor is said to have borne, ever deeply impressed upon his heart, the memory of that fatal disaster. Never thereafter did he exhibit the gaiety of spirit which had been so characteristic of him or show himself joyful before his people, no matter how much they entreated him. Never, as long as he lived, did he enjoy the good health which before that time he had possessed in so remarkable a degree. In short, the ever-present memory of that defeat so oppressed him that never again did he enjoy peace of mind or his usual tranquillity of spirit....

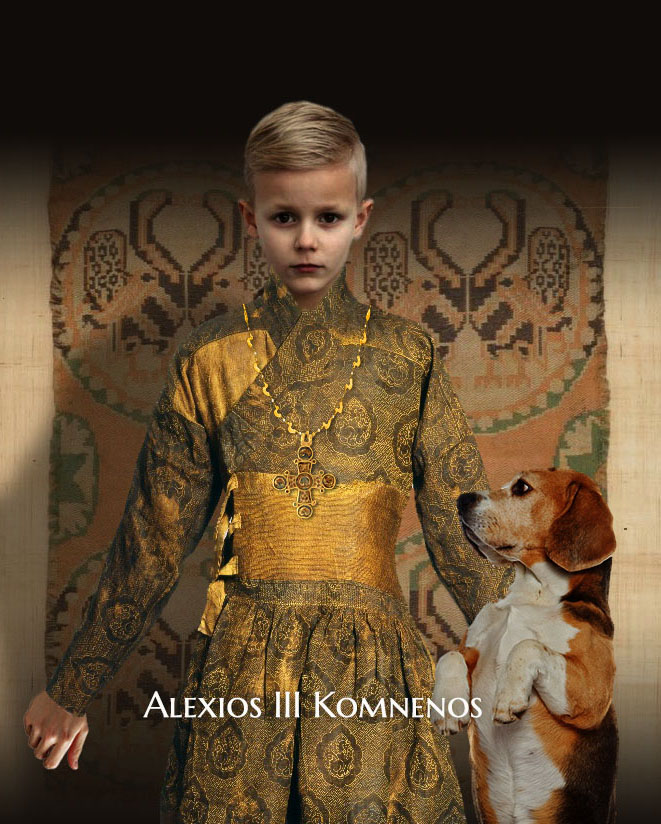

When Lord Manuel died, that most fortunate emperor of indelible memory, he was succeeded according to both his will and the hereditary law by his young son Alexios, who had hardly reached his thirteenth year. . . . During the reign in God of the former beloved emperor, the Latin people found favor with him due to the emperor's trustfulness and vigor. He even disdained his Greek manikins, who were soft and effeminate, and, being a man of great generosity and incomparable activity, gave important assignments only to Latins, taking into consideration their fealty and strength. Because they prospered under his rule and enjoyed his generous liberality, the noble and ignoble of the whole universe eagerly collected around him, as around a great benefactor. As they accomplished their service quite well, he was induced more and more to appreciate our people, and promoted all of them to higher ranks. Therefore the Greek nobility, and especially his relatives, as well as the rest of the populace, acquired an insatiable hatred toward our men.

When Lord Manuel died, that most fortunate emperor of indelible memory, he was succeeded according to both his will and the hereditary law by his young son Alexios, who had hardly reached his thirteenth year. . . . During the reign in God of the former beloved emperor, the Latin people found favor with him due to the emperor's trustfulness and vigor. He even disdained his Greek manikins, who were soft and effeminate, and, being a man of great generosity and incomparable activity, gave important assignments only to Latins, taking into consideration their fealty and strength. Because they prospered under his rule and enjoyed his generous liberality, the noble and ignoble of the whole universe eagerly collected around him, as around a great benefactor. As they accomplished their service quite well, he was induced more and more to appreciate our people, and promoted all of them to higher ranks. Therefore the Greek nobility, and especially his relatives, as well as the rest of the populace, acquired an insatiable hatred toward our men.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints