By Niketas Chonates from O City of Byzantium

The following events also took place at this time. Setting out from Kypsella, the emperor came to Thessaloniki and then marched out against Chrysos. The latter had occupied Strummitsa, where he took possession of a certain fortress called Prosakos, and made it into a tyrant's dwelling for himself, strenthening in diverse ways the walls which Nature from the beginning had generously provided and fashioned; these are abrupt and cloven cliffs which abut upon one another, reached by a single narrow, steep, precipitous ascent, and the remaining circumference of the cliffs are sheer and inaccessible. The deep-eddying Axios River, winding around, provides an even more uncommon defense. Afterwards Art, rivaling Nature, made them very nearly impregnable: provided with a solid wall along the inside of the ascent, a formidable rampart was erected.

In the past the Romans had neglected the fortification of Prosakos, and since they were no longer troubled by the Bulgarians, they abandoned it. By making additions to Prosakos, Chrysos had a dwelling place which could not be taken by the Romans. He placed stone-throwing engines round about and collected weapons and food supplies, and flocks of sheep and herds of cattle were put to graze along the mountain ridges. It is not easy to define the perimeter of the fortress, for it spreads out in width and length, extending into the rain forests and thickly wooded places. Only one indispensable and essential advantage was lacking: not a single drop of water trickles there, nor are there wells, making necessary the descent to the river to draw water in pitchers. In possession of such a fortification, Chrysos was not at all disturbed by the fact that the emperor was marching against him but made preparations to oppose him.

Those Romans who were experienced in warfare-indeed, if there were any such left at that time-and who were informed of the features of the land, deemed it necessary, and advised the emperor accordingly, to bypass Prosakos and to attack the remaining towns and villages obedient to Chrysos; only after subduing these should he advance against Prosa- kos. Thus the morale of the troops would be high because they would first destroy those places that were easy to overcome and come into possession of booty. Chrysos, on the other hand, constrained by compelling circumstances, might alter his plans to the advantage of the Romans by surrendering or by despairing of his situation. They argued that on the first assault against the impregnable fortifications and attempt to scale the precipitous mountains-even if such were not futile-they could envision bloody sweat, great suffering, and the decapitated heads of fighting men.

These were the recommendations on the one side. The castrated chamberlains fiercely opposed them; they were led by George Oinaiotes and the retinue of beardless striplings. These most clever and long-time attendants of the emperor persuaded him to lead the army straight to Prosakos, to carry the war to Chrysos, and to brandish the spear, asserting:

Should he [Chrysos] be taken captive, then none will resist us in the future. Moreover, what prevents us from attacking the most vital area straightway instead of engaging the enemy periodically and seasonally? Why should anyone tolerate tarrying for long in these barbaric and disagreeable lands for no gain or only some small advantage at a season [summer 1197161] when the Propontis is heavily laden with figs, melons, and other fruits of the earth which, planted by the hand of God in paradise, are now beginning to ripen. Would that we were standing on the plain of Rhegion gazing out over Aphameia and hailing holy Constantinople, sailing out to the luxuriant districts along the Pontos where the gentle, cool, life-giving north breeze ever blows, where newly caught fish jump about and dolphins playfully leap in all directions, where the delights of bathing beckon everywhere and the lapping of silver waves invigorate the spectator, where twittering swallows cast their spells, where warbling nightingales provide a feast for the ears of those who wander about hither and yon, and all manner of birds chirp here and there in the thickets and pipe their melodies on the wing.

The emperor rode full speed towards Prosakos to turn their reasoning into reality. Along the way several fortifications were razed, piles of fruit and wheat fields were burned to ashes, and the Turks who were sent to the emperor as allies by the satrap of the city of Ankara took Vlachs captive by the spear. Those who were sound of doctrine and devoted to the Orthodox faith earnestly entreated the emperor not to allow the Turks to transfer to their own country people who worship the same God we profess, so that by being compelled to abjure their faith, they should anger the Divinity against those who gave them up. They asked instead that the Vlach captives be given to the Romans to be their servants and that the Turks who had taken them prisoners should be favored with other imperial pledges of friendship, but the emperor rejected their counsel outright.

After Alexios had arrived at Prosakos and had set up camp, he decided to make an attempt on the fortress at once. The deeds performed by the Romans at that time were indeed worthy of gifts of honor and wonder: they fought beyond all expectation. They who were armed with shields and bare swords and they who bore bows and arrows scrambled up the steep slopes around the fortress, and, drawing near, they smote the defenders on the walls and in the citadel. After much toil and slaughter, they drove the barbarians back from the advanced fortification which had recently been constructed as an outpost to protect the gates in this section. There were those who scaled the steep slopes nimble-footed as wild goats in an attempt to penetrate the walls and rush the citadel. Just when they thought that they had accomplished a salutary and mighty deed, having chased the defenders from the walls and shut them inside, they realized that they had labored in vain; when they called for mattocks in order to pull down the walls, there was no one to furnish the required tool. But they persisted in this labor, grumbling against the officers in charge of the imperial tools. Using their hands and swords as crowbars,'36a they detached the stones from their joints; then, leaping up, they pulled down the bulwark. Later, but too late, for the work was under way and they were being harried by the enemy attacking them from above, the official in charge of the tools, a eunuch, arrived carrying mattocks bound together by a rope. The scoundrel should have been drowned forthwith or made to pay miserably for his actions as a brief respite for those who had suffered from combat as well as thirst and suffocation caused by the sun's burning heat, but he prudishly rebuked them and with a loud smacking of the lips pretended to be vexed and quelled the resolve of these courageous men. Next they asked for ladders to scale the walls, but again there were none to be found. At this, they could no longer continue to toil without any hope of success, and they unwillingly departed.

After Alexios had arrived at Prosakos and had set up camp, he decided to make an attempt on the fortress at once. The deeds performed by the Romans at that time were indeed worthy of gifts of honor and wonder: they fought beyond all expectation. They who were armed with shields and bare swords and they who bore bows and arrows scrambled up the steep slopes around the fortress, and, drawing near, they smote the defenders on the walls and in the citadel. After much toil and slaughter, they drove the barbarians back from the advanced fortification which had recently been constructed as an outpost to protect the gates in this section. There were those who scaled the steep slopes nimble-footed as wild goats in an attempt to penetrate the walls and rush the citadel. Just when they thought that they had accomplished a salutary and mighty deed, having chased the defenders from the walls and shut them inside, they realized that they had labored in vain; when they called for mattocks in order to pull down the walls, there was no one to furnish the required tool. But they persisted in this labor, grumbling against the officers in charge of the imperial tools. Using their hands and swords as crowbars,'36a they detached the stones from their joints; then, leaping up, they pulled down the bulwark. Later, but too late, for the work was under way and they were being harried by the enemy attacking them from above, the official in charge of the tools, a eunuch, arrived carrying mattocks bound together by a rope. The scoundrel should have been drowned forthwith or made to pay miserably for his actions as a brief respite for those who had suffered from combat as well as thirst and suffocation caused by the sun's burning heat, but he prudishly rebuked them and with a loud smacking of the lips pretended to be vexed and quelled the resolve of these courageous men. Next they asked for ladders to scale the walls, but again there were none to be found. At this, they could no longer continue to toil without any hope of success, and they unwillingly departed.

As the Vlach defenders of the walls later verified, there was no question that the fortress would have fallen and Chrysos would have been taken prisoner (this deed would have been auspicious for the Romans, and much trouble would have been avoided thereafter) had the tools for the demolition of the wall been ready beforehand and supplied when needed. Now this was the consequence of the negligence of duty or perhaps God himself (may God be merciful to us if in foolishness we question his judgments), displeased"" with the men of those days, op- posed their feats in battle.

As the Vlach defenders of the walls later verified, there was no question that the fortress would have fallen and Chrysos would have been taken prisoner (this deed would have been auspicious for the Romans, and much trouble would have been avoided thereafter) had the tools for the demolition of the wall been ready beforehand and supplied when needed. Now this was the consequence of the negligence of duty or perhaps God himself (may God be merciful to us if in foolishness we question his judgments), displeased"" with the men of those days, op- posed their feats in battle.

Thus did the Romans contend hotly on that day, and thus did they disperse. On the next day they marched out for a second encounter and found the enemy fighting with high spirits and boasting because of yesterday's encounter. The barbarians' stone-throwing engines killed not a few, discharging the stones from on high with great success. The man responsible for discharging the stone missiles, turning round the withe and aiming the sling, was an excellent engineer; once he had served the Romans for pay, but when his salary was not forthcoming, he returned to Chrysos. The troops were battered not only by the rounded stones hurled from the stone-throwing engines but also by the stones rolled down upon them from above. Often the large stones that did not hit their mark nonetheless killed those in whose vicinity they fell. Dashed against the rocky peaks below, the stones were shattered by the force of the discharged missiles, and the many fragments that scattered in all directions were a death-dealing evil.

Under the cover of night, the barbarians came out from behind the walls and destroyed the siege engines that the Romans had positioned on the hills, and the terrified troops on night watch fled straight to the tent of the protovestiarios John. Bewildered by the tumult, he leaped from his bed just as he was, and swooning and quivering from fear, he took to flight. The enemy divided among themselves the contents of the tent in which were found the frog green buskins of the protovestiarios and spent the whole night mocking and laughing at the debacle of the Romans. Moreover, the din made by letting down hollow, drum-like wine jars bound by willow twigs confounded the troops who did not know what was happening because of the darkness.

The emperor despaired of achieving his purpose and, not at all disposed to tarry in these parts any longer, sued for peace. He ceded Prosakos, Strummitsa, and the lands round about to Chrysos, and although the latter did not lack a wife, he agreed to give him one of his kinswomen in marriage. Upon entering Byzantion he divorced the protostrator's [Kamytzes] daughter from her husband and sent her to Chrysos, appointing the sebastos Constantine Radenos to escort the bride. When the marriage rites had been celebrated and the nuptial banquet was served, Chrysos drank neat wine and gorged himself with food; his bride, respecting the code of behavior for newlyweds, ate abstemiously of the dishes set before her. Commanded by the groom to partake of the food with him, she did not comply immediately and drove her husband into a fury. For some time, he muttered to himself in his barbaric tongue and remained angry and later remarked with contempt in the Hellenic language, "Do not eat or drink.

The emperor despaired of achieving his purpose and, not at all disposed to tarry in these parts any longer, sued for peace. He ceded Prosakos, Strummitsa, and the lands round about to Chrysos, and although the latter did not lack a wife, he agreed to give him one of his kinswomen in marriage. Upon entering Byzantion he divorced the protostrator's [Kamytzes] daughter from her husband and sent her to Chrysos, appointing the sebastos Constantine Radenos to escort the bride. When the marriage rites had been celebrated and the nuptial banquet was served, Chrysos drank neat wine and gorged himself with food; his bride, respecting the code of behavior for newlyweds, ate abstemiously of the dishes set before her. Commanded by the groom to partake of the food with him, she did not comply immediately and drove her husband into a fury. For some time, he muttered to himself in his barbaric tongue and remained angry and later remarked with contempt in the Hellenic language, "Do not eat or drink.

At that time [late 1197 and 1198 (1199?) an onslaught of Cumans mightier and more dreadful than ever before took place. Dividing their forces into four armies, the Cumans overran all of Macedonia, attacking well-fortified cities and ascending mountain peaks; in searching Mount Ganos, they despoiled many monasteries and killed monks, for none dared to raise a hand against them out of fear of the enemy's superiority in numbers, and they preferred to save their own skins.

The emperor, who saw that his young and beautiful daughters eagerly desired a second marriage, carefully selected their future husbands, choosing rulers of nations who professed the Christian faith and whom he feared as enemies. Later he changed his mind and married them to Romans, joining Irene in marriage to Alexios Palaiologos after he had first divorced his lawful wife, a beautiful woman descended from a noble family, and uniting Anna in wedlock to Theodore Laskaris, a daring youth and fierce warrior.

These unions took place at the approach of Shrove Sunday [1199 (February 1200?)] and while the father-in-law and emperor was not disposed to spend his leisure time at the horse races, the newlyweds insisted on seeing such spectacles. To please both himself and his sons-in-law, the emperor did not come to the Great Palace, nor did he go to the stadium, but instead ordered the racing chariots brought to the palace in Blachernai, where he improvised a theater. The bellows of the pipe organs were positioned as turning points in the courtyard, and a eunuch played the role of eparch of the queen of cities; I intentionally omit his name, but he was exceedingly wealthy, administered the highest offices, and was a member of the imperial court. Girding himself with a wickerwork (which in common speech is called wooden ass) covered with a horsecloth made from one piece and adorned with figures and shot with gold, he entered the improvised theater. It was quite a sight to see him as both magnificent horseman and neighing and prancing horse, obedient to the rein; shortly afterwards, he dropped the role of mounted eparch and took up that of mapparius. And they who put on the gymnastic contest were not the vulgar and baseborn, mind you, but youths of noble family growing their first beard. Only the emperor and empress and their distinguished relations and most trusted attendants viewed this comic play-acting; entrance was barred to all others. When the time arrived for the gymnastic contest of running the double-course race, the eunuch who played the role of mapparius took his position in the center, uncovered his arms, and putting on a round silver headdress, thrice summoned the lads to get set for the race. A certain noble youth, notable for the lofty rank he held, stood behind the eunuch, and whenever the latter bent over and gave the signal for the race to begin, he would kick him so hard with the flat of his foot on the buttocks that the noise could be heard everywhere.

These unions took place at the approach of Shrove Sunday [1199 (February 1200?)] and while the father-in-law and emperor was not disposed to spend his leisure time at the horse races, the newlyweds insisted on seeing such spectacles. To please both himself and his sons-in-law, the emperor did not come to the Great Palace, nor did he go to the stadium, but instead ordered the racing chariots brought to the palace in Blachernai, where he improvised a theater. The bellows of the pipe organs were positioned as turning points in the courtyard, and a eunuch played the role of eparch of the queen of cities; I intentionally omit his name, but he was exceedingly wealthy, administered the highest offices, and was a member of the imperial court. Girding himself with a wickerwork (which in common speech is called wooden ass) covered with a horsecloth made from one piece and adorned with figures and shot with gold, he entered the improvised theater. It was quite a sight to see him as both magnificent horseman and neighing and prancing horse, obedient to the rein; shortly afterwards, he dropped the role of mounted eparch and took up that of mapparius. And they who put on the gymnastic contest were not the vulgar and baseborn, mind you, but youths of noble family growing their first beard. Only the emperor and empress and their distinguished relations and most trusted attendants viewed this comic play-acting; entrance was barred to all others. When the time arrived for the gymnastic contest of running the double-course race, the eunuch who played the role of mapparius took his position in the center, uncovered his arms, and putting on a round silver headdress, thrice summoned the lads to get set for the race. A certain noble youth, notable for the lofty rank he held, stood behind the eunuch, and whenever the latter bent over and gave the signal for the race to begin, he would kick him so hard with the flat of his foot on the buttocks that the noise could be heard everywhere.

These boyish games were not yet finished when dreadful news brought an end to the amusements: Ivanko had rebelled at Philippopolis. As we stated above he was renamed Alexios and became the emperor's grandson-in-law. Taking upon himself more power than was fitting, he was appointed general and received the command over the very troops which were set over against his own countrymen, the Vlachs, in the province of Philippopolis. Indeed, when he made his appearance as master of the territories in those parts, he did as he willed, for since he was flexible and energetic, he was capable of accomplishing any task to which he put his heart and mind. He trained his countrymen under his command in warfare, enriching them with gifts and strengthening them with armaments; the mountains opposite Haimos were fortified and became almost unassailable.

These boyish games were not yet finished when dreadful news brought an end to the amusements: Ivanko had rebelled at Philippopolis. As we stated above he was renamed Alexios and became the emperor's grandson-in-law. Taking upon himself more power than was fitting, he was appointed general and received the command over the very troops which were set over against his own countrymen, the Vlachs, in the province of Philippopolis. Indeed, when he made his appearance as master of the territories in those parts, he did as he willed, for since he was flexible and energetic, he was capable of accomplishing any task to which he put his heart and mind. He trained his countrymen under his command in warfare, enriching them with gifts and strengthening them with armaments; the mountains opposite Haimos were fortified and became almost unassailable.

The emperor was lavish in his praise when he learned of these things. In his great regard for Alexios, he indulged him with many bounteous gifts, and he gladly heard him and readily granted his requests. When the emperor's counselors observed the man's actions, they declared them to be excellent and well done but added that in truth his intention was not to benefit the Romans. For this reason, they advised the emperor to dismiss Alexios from his command. It is not feasible that a barbarian who but short while ago was a mighty adversary of the Romans should suddenly reverse himself, that in all innocence he would build new fortresses and towns on advantageous sites and increase the numbers of his own countrymen in the army while diminishing those of the Romans. He would have been an intractable foe had not the idea been sowed in his mind to establish his own tyranny, for, as some men do not like to express their thoughts by ways of the lips' portals, their actions often speak louder than words in disclosing the secrets of the mind.

The emperor was lavish in his praise when he learned of these things. In his great regard for Alexios, he indulged him with many bounteous gifts, and he gladly heard him and readily granted his requests. When the emperor's counselors observed the man's actions, they declared them to be excellent and well done but added that in truth his intention was not to benefit the Romans. For this reason, they advised the emperor to dismiss Alexios from his command. It is not feasible that a barbarian who but short while ago was a mighty adversary of the Romans should suddenly reverse himself, that in all innocence he would build new fortresses and towns on advantageous sites and increase the numbers of his own countrymen in the army while diminishing those of the Romans. He would have been an intractable foe had not the idea been sowed in his mind to establish his own tyranny, for, as some men do not like to express their thoughts by ways of the lips' portals, their actions often speak louder than words in disclosing the secrets of the mind.

But these wise opinions were directed to ears that heard not, for the emperor, assuming his granddaughter's wedding to be a pledge of loyalty, deemed Alexios to be completely trustworthy and innocuous, beguiled, I believe, by the maleficent power which ever led the Roman state to her ruin. Not long afterwards, that which was feared became reality. Dumbfounded by the news, the emperor did not know what to do because the evil had erupted unexpectedly. Seeing how difficult it would be to levy troops, he immediately dispatched a certain eunuch, his most trusted friend, to the rebel Alexios [c. March 1199 (1200?)] to remind him of their compacts, so that nothing unpleasant should befall him. Although Alexios was unworthy of those hopes which the emperor had held, the emperor did not despair of the rebel changing his mind. The next day, the emperor's newly married sons-in-law marched out together with his near friends and kinsmen.

When the wicked eunuch reached Alexios, he did nothing to effect the purpose of his mission but by his presence encouraged him in the task at hand. He warned him of the imminent arrival of the Romans who had set out against him and instructed him to avoid the plains and take to the mountains where he and his troops, consisting of his fellow countrymen who had joined him in his rebellion, would be safe. The troops under the command of the emperor's sons-in-law and of the protostrator Manuel Kamytzes pursued the rebel energetically with admirable eagerness, and everyone wished to play the leading role. However, they lost the opportunity for victory because the prey was frightened away, and they relaxed their effort.

The more impetuous felt that they should pursue Alexios in the mountains to which he had escaped; the more cautious were not at all eager to grope for the track of an eagle flying over crags and mountains, or to search after the creeping of a serpent on a rock, or to enrage a ferocious wild boar into combat and thus expose the breast to be gored; nor were they eager to surround the fortresses which Alexios had restored and erected and to make them obedient to the emperor. This latter counsel being determined as the better, they made an assault upon the fortress built by Alexios at the foot of the mountain at a place called Kritzimos. The Romans labored mightily and competed with one another in daring, and not a few nobles were lost while bringing the scaling ladders to the walls, the foremost among whom was George Palaiologos. Finally destroying the fortification, they subjugated other adjacent small towns; some were subjugated with blood, while others capitulated.

Alexios, who was ingenious and prolific in deeds of war, demonstrated in his campaigns against the Romans his complete command of military tactics; at the last he resorted to the following most clever stratagem and overpowered the protostrator. He hit upon the idea of transferring large herds from the summits to the plain; these he delivered together with a contingent of Roman captives, to his fellow countrymen in the vicinity of the Haimos with instructions to bring them to Ioannitsa, the governor of Zagora, as his share of the spoils and as a reward for having allied himself with Alexios and having made covenants against the Romans. Then he entrapped the Romans by lying in ambush. He knew well the greed and rapacity of the men, aware of the fact that when the Romans chance upon a windfall, they will lay down their lives for it, at once, with no concern for their own safety. And indeed, shortly afterwards, he had the Romans doing exactly what he had turned over in his mind. As soon as the protostrator heard what was happening, he set out from Batrachokastron, where he had pitched camp, and came to Baktounion. Taken in by appearances and oblivious to Alexios's ruse, he allowed his troops to plunder everything in sight while he walked about, observing what was taking place. Emerging from the ambushes, Alexios encircled the protostrator, and, spreading his troops like a dragnet or seine, he killed the commander's companions and took him alive. The rebel's stratagem com- pletely unnerved the remaining Roman troops, and the rebel forces were elated.

The Romans, no longer effective, did not have the boldness to oppose Alexios in doubtful combat but preferred to stay close to Philippopolis lest Alexios bring this city also to terms. As was to be expected, he made himself master of all the small towns and fortresses which had been raised on the heights of the mountain passes over against the Haimos, situated on equally rough terrain, nor did he leave behind the others to remain as they were but incited to rebellion against the Romans all those towns and fortresses leading down to Mosynopolis, and reaching as far as Xantheia, and stretching out towards Mount Pangaios, and up to Abdera. Furthermore, he subjugated the theme of Smolena and spread over the neighboring lands like a contagious disease, removing Romans and killing them and receiving ransom for others; his own countrymen who willingly sided with him, he allowed to remain on their lands.

Ever extending his sway, he was far worse than earlier rebels, and he was driven to such cruelty, which most barbarians deem to be manliness, that while carousing, he ordered the Romans taken in battle torn limb from limb. The emperor, as his actions demonstrated, reckoned the protostrator's capture a godsend, a delightful and excellent piece of good luck. Making a diligent search of all his assets, he laid his hands on the man's immense riches that befitted a monarch; he also sentenced his wife and son to prison, on what grounds I know not. As spring was coming to a close, he set out for Kypsella [before 21 June 1200]

At this time the doctrine on the Holy Sacraments was brought to light and divided the Christian flock into opposing factions; and those things which merited both honor and silence were loudly contemned in the agora and on the crossroads by anyone who wished to do so. After George Xiphilinos, who governed the church for seven years [10 September 1191 to 7 July 1198], John Kamateros ascended the patriarchal throne ; he deemed it necessary to cut down root and branch the doctrine which first sprang up and was whispered about in the days of Xiphilinos, to subject to anathema its author, the false monk Sikidites, as an heresiarch who introduced novel doctrines, and to prevail upon the others to remain silent following his own example, contending that the mystery remains a mystery. Sikidites resorted to dialectical tricks and strained proofs, relying on strange and unseemly arguments introduced from outside. Moreover, he composed catechetical sermons on the occasion of the commencement of Lent in order to salve in their struggle those who have undertaken the spiritual battle, making mention in turn of the doctrine. In this he discussed certain opinions of his own but committed the arguments of his adversaries to silence in order, I believe, to avoid their refutation; in attacking the doctrine, he accused them of certain ideas of which they were entirely ignorant or had never conceived.

The point at issue was whether the Sacred Body of Christ taken in communion is incorruptible, as it was after the Passion and Resurrection, or whether it is corruptible, as it was before the Passion. They who contended that it was incorruptible cited the great theologian Cyril, according to whom the partaking of the Sacred Mysteries [Holy Communion] is a confession and remembrance of the death and resurrection of the Lord for oursakes, that whoever receives but a portion takes in whole Him who was handled by Thomas and that, according to John of the Golden Tongue [Chrysostom], He is eaten as He was after the Resurrection, and they put forward the words of Eutychios, the light of the Church; One receives the whole of the Sacred Body and Precious Blood of the Lord, even though one partakes of but a portion of them. Heis divided indivisibly in all because of the mingling, in the same manner that a seal stamps its impressions and configuration on receptive substances and remains the same after the imprint has been made, neither diminished nor altered by the stamped objects, even though they should be more in number; so does the sound of the voice, emitted and projected through the air, remain whole in its utterance and is carried intact through the air to the hearing of all, and none of those who hear it perceives more or less than any other, for it stays indivisible and whole for all, even though the hearers should be ten thousand or more in number; furthermore it has a substantiality of its own for the sound of the voice is nothing else but air in vibration. Let no one have any doubt that the Incorruptible, Immortal, Sacred, and Life-giving Blood and Body of the Lord after the Mystic Sacrifice and the Holy Resurrection, which is eaten in the antitypes by way of the Divine Liturgy, are not only less diminished than the aforementioned examples in imparting their vital forces but are found whole in all.

While the one faction put forward these arguments and introduced the testimony of a large number of the doctors of the Church, the other faction contended that the consecrated elements of Body and Blood' were not a confession in the resurrection but only a sacrifice; consequently the Body was corruptible, lacking both mind and soul, and the communicant did not receive the whole Christ but only a portion, since he partakes of only a portion. "For if," they asserted, "the Body were immortal, having mind and soul, and it would be impalpable and invisible, incapable of being chewed and ground by the teeth, nor would it be able to endure being divided,""" for it appears that they denied the resurrection of the Body; they contended (as if they knew) that after the resurrection we will neither be subject to touch and sight nor have human form, but that we will flit about like incorporeal shadows,'385 maintaining that the Lord's entrance through shut doors1786 was no miracle but only that which is natural and fitting to those who have risen from the dead. One can find no such thing, however, in the Scriptures, and this doctrine was the shameful and unattested revilement of a certain few who main- tained that only after the union and communion [of the Body and Blood], the Lord's human nature1387 became incorruptible and divine, and for this reason they believed that that which was received in Holy Communion'388 became incorruptible.1389

The emperor, having sided with the better opinion [May 1200], arrived, as I have said, at Kypsella. With the troops that had assembled there, he went up to Orestias. After a goodly number of days, he was overcome by a sense of helplessness, for he realized that the rebel was unconquerable and his own army, terrified at the mere mention of the enemy, was opposed to giving battle. The majority of the populace deemed he would take hurried flight. They thought that his very presence was a cause for disgrace, since he had accomplished nothing useful what- soever and his reluctance to give battle only encouraged the barbarian to be overbold. Clucking and cringing because of the harsh and difficult circumstances of the times, he dispatched his most trusted envoys to Alexios, inviting him to make peace. He gave thought as to how to slay him in some way by treachery without at all giving up the idea of joining battle.

The emperor and his troops made their way to the province of Philippopolis and encamped around the fortress of Stenimachos, wherein many of the barbarians had taken refuge. Laying siege with his forces, he took it by storm and enslaved those within. The rebel refused to meet with the emperor, nor would he agree to any peace terms unless the emperor first gave up all claim to the provinces and cities which he had subdued and sent to him his promised bride Theodora, together with the insignia of office.

After the treaties and sworn compacts had at last been negotiated [c. July 1200] according to the demands of Alexios, the emperor devised a scheme which I do not know if it be fitting to generals and emperors, since they, above all others, are required to keep their oaths. To lure Alexios, he dispatched his eldest son-in-law Alexios with imperial instructions, and after the execution of the sworn compacts, as I have said, he had him seized and put in chains. Henceforth, the emperor prevailed without any trouble over the cities and fortresses once ruled by Alexios, and he put to flight his brother Mitos. Having accomplished these things, he returned to Byzantion.

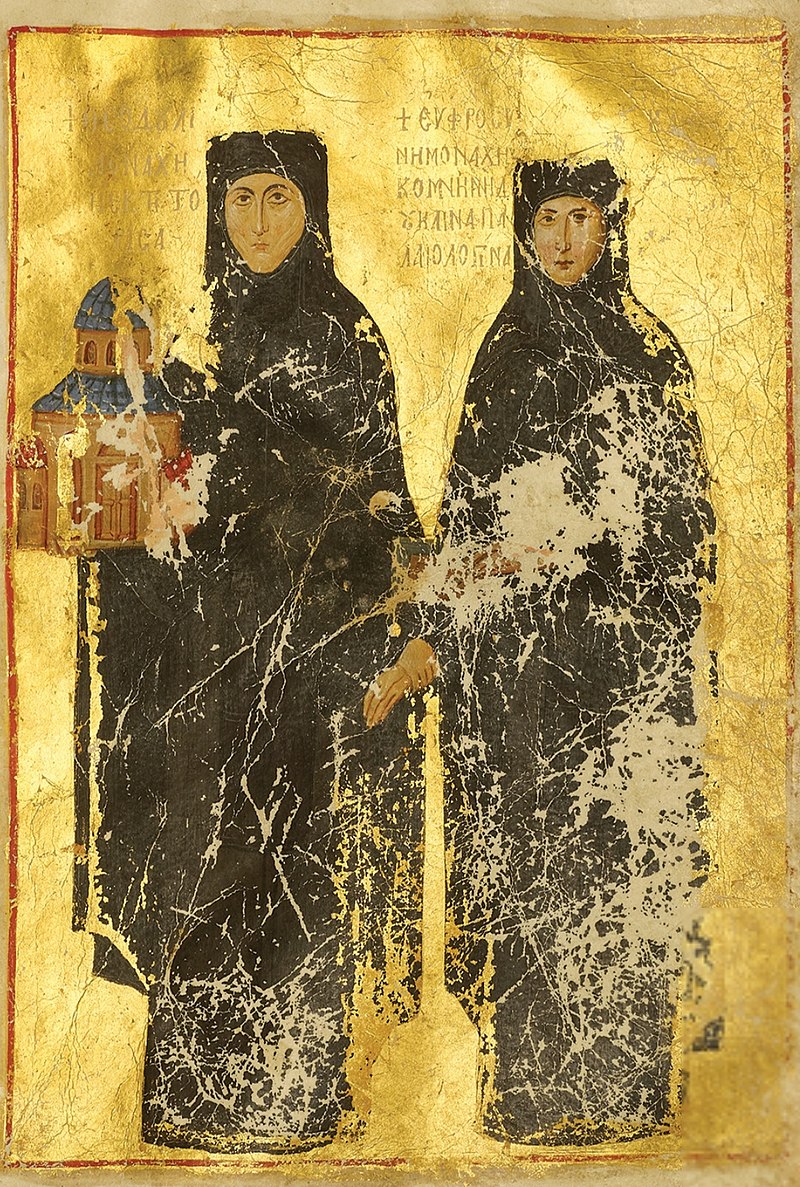

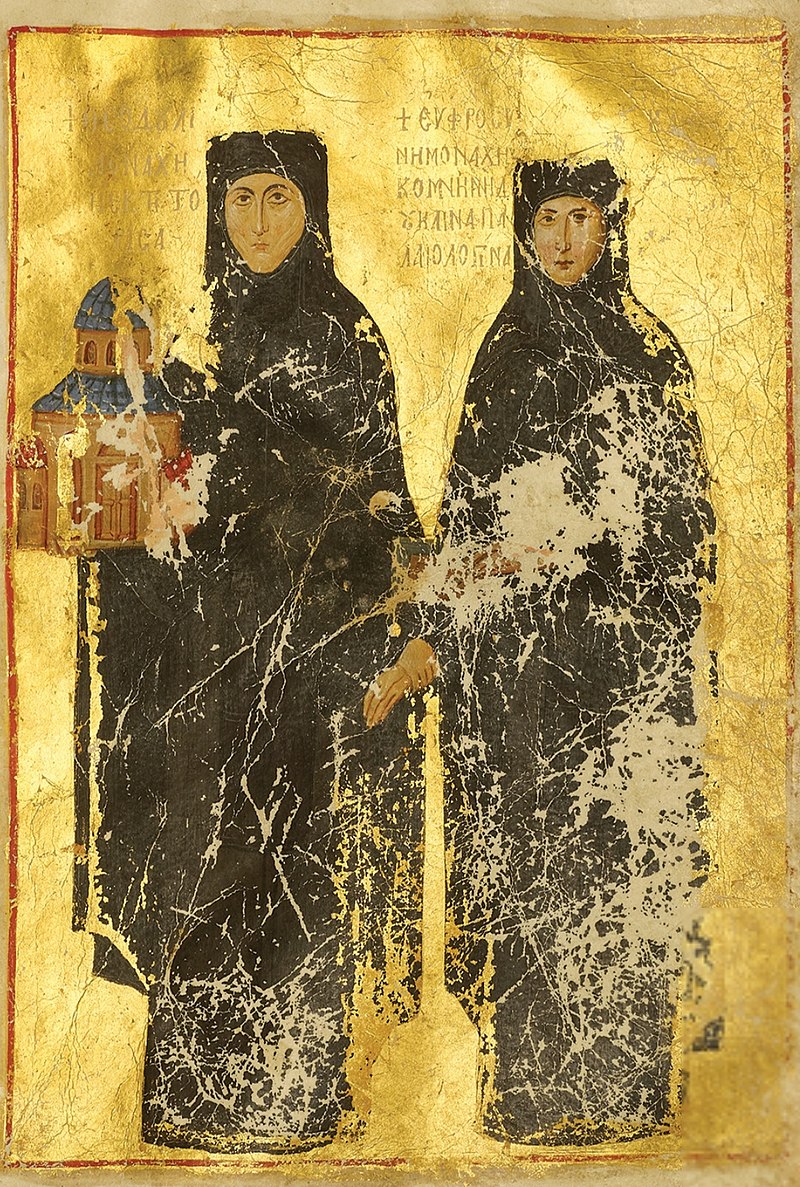

He found his wife Euphrosyne in no way content with keeping within doors but playing the man against seditionists and demagogues and unraveling the machinations woven by a certain Kontostephanos like the threads of Penelope. These things would not have been held in contempt, nor would they have excited wonderment from afar, had they been bound by limitations, but the empress's mad delusions and excessive zeal led her to believe that by inquiring diligently into the future, she could vitiate and dispel impending misfortunes even as the sun dissolves black clouds. In her predictions of things to come, she devoted herself to unspeakable rituals and divinations and practised many abominable rites.

She went so far as to cut off the snout of the bronze Kalydonian boar which stands in the Hippodrome with its back bristling and advances with projecting tusks against a lion, and she conceived of having the back of the gloriously triumphant Herakles, Lysimachos's most beautiful work, in which the hero holds his head in his hand and bewails his fate while a lions's skin is spread out over a basket, lacerated by repeated flogging.

0 Herakles, brave and great-hearted hero, the absurdity and folly of those things dared against you! Did a Eurystheus ever propose such a task for you? Did an Omphale, inflamer of amours and lascivious wench, treat you so disdainfully?

In addition to these shameful deeds, she removed the limbs from other statues and beheaded some with hammer blows. What did the City's populace not utter in disgust over these improprieties, and with what reproaches did they not dress down her who brought these to pass? Some of the vulgar populace trained those birds which mimic human speech, whose mouths are muzzled by nature so as not to sing, to repeat in the common speech this moral in the lanes and crossroads, "0 strumpet, a fair price if you please!""" The empress wore on her hand leather fitted around the fingers and shot through with gold, on which she held a bird trained to hunt game; going out for the chase, she clucked and shouted out commands and was followed by a considerable number of those who attend to and care after such things.

Not long afterwards, Kaykhusraw appeared before the emperor wearing a Persian conical cap on his head and dressed in raiment adorned with gold. But before continuing the history from this point, I shall first discuss the Turk's lineage.

To the Ikonian Kilij Arslan, who in former years was a most formidable foe of Emperor Manuel and was crowned with victory in battle, were given many sons. To Mas`ud [Muhyi al-Din] he allotted Amaseia and Ankara, prosperous Pontic cities; Qutb al-Din governed Melitene and Koloneia together with Kaisareia; Rukn al-Din was given Aminsos, Dokeia, and other coastal cities to rule. This Kaykhusraw ruled Ikonion, Lykaonia, and Pamplylia and governed all the land stretching to Kotyaeion.

To the Ikonian Kilij Arslan, who in former years was a most formidable foe of Emperor Manuel and was crowned with victory in battle, were given many sons. To Mas`ud [Muhyi al-Din] he allotted Amaseia and Ankara, prosperous Pontic cities; Qutb al-Din governed Melitene and Koloneia together with Kaisareia; Rukn al-Din was given Aminsos, Dokeia, and other coastal cities to rule. This Kaykhusraw ruled Ikonion, Lykaonia, and Pamplylia and governed all the land stretching to Kotyaeion.

When Qutb al-Din departed this life, Rukn al-Din, who held sway over Dokeia, and Mas`ud, the ruler of Ankara, contended hotly over this satrapy. Rukn al-Din, who was more clever by nature and exulted exceedingly in warfare, outdistanced his brother and rival and carried off the victory. Since Mas`ud submitted and agreed to a covenant of friendship, the more powerful Rukn al-Din took possession of only a portion of Mas`ud's toparchy and allowed him to govern there as before. He was especially maddened, however, by Kaykhusraw and suffered a burning passion for Ikonion, the paternal seat of government; he also loathed him for having a Christian mother. Through envoys, he advised Kaykhusraw to withdraw from Ikonion and remove himself from all power if he wished to perform a good service and spare the cities and the individuals and nations therein from the horrors of war. Thus did the barbarian boast, unsurpassed in his arrogance, his eyebrows raised above the clouds in scorn, as he poured out and scattered his deadly venom in many directions.

A truce was proclaimed and Kaykhusraw came to the emperor, emulating the example of his father who had also wronged his kinsmen and been wronged by them after the death of his father Mas`ud, for he had regarded Emperor Manuel as a sacred anchor and a firm hand capable of supporting him. But Kaykhusraw's hopes were not realized, for he met with a response that was less than anticipated. He received but few favors and these, to say the least, insufficient to what he had in mind; finding no support in his opposition to his brother, he returned home.

He had barely made his entrance into Ikonion when Rukn al-Din launched an attack against him. He was ejected from the throne and fled as a fugitive to Leon of Armenia. His reception was not cold but cordial and pleasant, even though they had many times gone to war against one another, for men like to deem worthy of compassion not only

their kinsmen and coreligionists but also foreigners who, although having shown themselves oftimes to be adversaries, approach and fall at their feet. However, Leon absolutely refused to undertake his defense and restore him to his former dominion, contending that he had made peace with Rukn al-Din and that such assistance could only lead to bloodshed.

For these reasons, Kaykhusraw made his way back to the emperor, imagining that he would assuredly receive his help in recovering his throne. But among the Romans, he failed once again and was not accorded the least treatment befitting his noble birth.

The following year [1 September 1200 to 31 August 1201?], when the Vlachs, joined by the Cumans, ravaged the best lands of the province, they returned unscathed. Indeed, they would have reached the very land gates of the queen of cities in their onslaught had not the most Christian nation of the Rhos [Russians] and their chiefs been moved to attack of their own volition, giving way to the entreaties of their own chief shepherd. They displayed admirable zeal in their concern over the fortunes of the Romans, as they were unable to endure their frequent abductions throughout the year and their being delivered over to non-Christian barbarian nations. Whence Roman, the ruler of Galicia quickly collected a large and gallant army and hastened against the Cumans; overrunning their land with great ease, he wasted and destroyed it. These kind deeds he performed often to the glory and greatness of the unblemished faith of the Christians, the smallest part of which, like the mustard seed, can remove and transport mountains. Thus he put an end to the Cuman raids and awarded a respite from their tribulations to the utterly ruined Romans to whom he and his army appeared as an unexpected succor, an incalculable host of shield-fellows, and a phalanx, collected by God, so to speak, to a nation sharing the same faith.

The same year, however, was not to leave these Tauro-Scythians without factional strife, as both Roman and Rurik, the prince of Kiev, reddened their swords with the slaughter of their fellow countrymen. Roman, strong of body and mighty with his hands, carried away the victory and laid low many of the Cumans who had joined Rurik in battle, constituting a powerful and valiant phalanx around him.

But this too must not pass unrecorded. There was a certain money-changer, Kalomodios by name. He was laden with much money, and, greedy of gain, he often set forth on long and arduous journeys for purposes of trade. A skinflint who slept with his wallet and placed everything second to making money, he often provided the gold-hunting emperors with the occasion to view him as the richest of men and as Alkinoos's orchard, where, in but a moment, not pear bore pear and fig yielded fig but gold brought forth gold and silver produced silver. He was undisguisedly the tree of knowledge planted in the City's agora and lanes as though in the garden of Eden. ancestor

Just as long ago the fruit's full bloom enslaved our first did the gold's gleam tempt the emperor's financial officers to gather it in. But as soon as they laid hands on Kalomodios, they stirred up the City to sedition as though they had suffered a worse calamity than our first parents. They who plucked and ate of the fruit and did not confine their gluttony to sight only were justly punished, while they who were too late even to gaze upon the wealth searched in vain with mouths agape and suffered the thirst of Tantalos. In possession of the fount, they could not drink therefrom, but rushing often to draw water, they found it disappearing from their very hands. When the vulgar masses learned of Kalomodios's arrest that evening and discovered the reasons, they gathered in groups at dawn and entered the temple of God, where they beheld the chief high priest (this was John Kamateros). They surrounded him and threatened to tear him asunder and cast him headfirst from the altar unless he dispatched letters to the emperor and played upon them like a panpipe, calling back Kalomodios to them like a lost sheep"" that had strayed from the flock. The patriarch barely managed to calm the clamorous populace by his eloquence; speaking brilliantly, with passionate ges- tures, he restored to them the man they sought as though he were a lamb but without his being fleeced of his gold by his wolf-like jailers, nor was a hair of his head harmed.

Thus this episode passed without bloodshed; beginning on a tragic and ominous note, it concluded in tumultuous comic sport and laughter mingled with tears. Not many days later, there erupted another evil which did result in the shedding of blood. A certain John, surnamed Lagos, who had received an appointment from the emperor to command the Praetorian prison, wished to obtain monies for himself and his officers from this post. (Alas! How terribly sordid the thought, for the convention of historical writing does not permit saying more.) To appropriate the alms of the lovers of God, at night he released from prison the most notorious thieves, still fettered in chains, and these furtively ransacked the houses and brought him the stolen goods. From the booty he distributed the prize of impiety to those lying in wait at night and the rest he offered to those to whom it was not proper to do so; completely faithless to God in his cowardly actions, he played the role of the faithful servant. Many accused him before the emperor of performing unholy deeds, but although he promised to amend his ways, he put it off as though he were unable to do so. In the same way, Lagos, who did not cower because of his shameless actions but wielded unaccountable power, performed his godless deeds with impunity.

It so happened that after one of these low fellows was seized, struck many lashes on the back, and condemned to have his hair cropped, the more hotheaded elements of the City and the victim's fellow artisans were fired to rebellion. Confusion befell the City, and no small number of artisans who gathered at the praetorium were eager to catch Lagos, but he disappeared quicker than a hare in flight. The populace fled together and hastened to enter the Great Church and proclaim another emperor. But the temple had been occupied in advance by the emperor's ax-bearing guard, and the crowds could only stay on at the praetorium and shout abuses against the emperor. The latter, who was not present in the City but was encamped somewhere near Chrysopolis, dispatched a company of his bodyguard to occupy the praetorium. The eparch of the City, Constantine Tornikes, also arrived there. The throng, infuriated by the mere sight of them, turned the eparch to flight by pelting him with stones and expelled the bodyguard. Breaking open the gates of the praetorium, they gave the prisoners license to loot the Christian church located there, and they destroyed the synagogue of the Saracens to its very foundations. Without reason, they marched on the so-called Chalke prison and perpetrated the same deeds there. With the arrival of imperial troops led by one of the emperor's sons-in-law (this was Alexios Palaiologos), they were held in check but did not withdraw altogether; at first unarmed and then with a few armed men alongside them, the mob engaged the troops clad in full armor, choosing to die without achieving any deed worthy of glory. There were those who appeared atop the roofs and flung down tiles and some threw stones as large as their hands could hold; others discharged arrows against the imperial ranks. Throughout the entire day their wrath was unabated, and they withdrew only towards evening. On the morrow they uttered not a sound, nor did they come running to fight a second battle.

As soon as this evil had passed, a member of the Komnenos family, John by name, rebelled against the emperor [31 July 1200 (1201?)] potbellied and with a body shaped like a barrel, he was nicknamed "the Fat." Without warning he slipped into the Great Church and placed on his head one of the small crowns which hung suspended all around the altar. He was joined by those who had sworn to support his cause (they were many and almost all were of noble blood), and when no small number of the masses who had learned what was afoot came running, they gained easy entrance into the palace. As he sat on a golden throne, John promoted certain of his followers to the highest offices, and the mob and some of the rebels poured through the agorae and the streets and reached the shore, where they proclaimed him emperor of the Romans and pulled down the magnificent dwellings there.

At nightfall, John neglected to set a guard over the palace as was necessary, nor did he restore the overthrown gates. Since no one had opposed him, he behaved as though he were safely ensconced; overcome by thirst because he was so corpulent, he emptied out whole jars of water, spouting like a dolphin, and boiled off the drops of perspiration that gushed forth as from a spring and evaporated from the heat. His troops went to the splendid Hippodrome but lounged about without any purpose, and at sundown the mobs dispersed like flocks of birds in their desire to rise up early so that they could come running together to once again fall upon the magnificent dwellings and search out their contents. The emperor gathered together his kinsmen and veteran troops and dispatched them early in the morning to attack John. Not even through the early dawn was the City's throng content to remain at rest; most were anxious to band together about the tyrant at the first break of day to assist him in his task and to fight against the imperial troops in many ways.

At nightfall, John neglected to set a guard over the palace as was necessary, nor did he restore the overthrown gates. Since no one had opposed him, he behaved as though he were safely ensconced; overcome by thirst because he was so corpulent, he emptied out whole jars of water, spouting like a dolphin, and boiled off the drops of perspiration that gushed forth as from a spring and evaporated from the heat. His troops went to the splendid Hippodrome but lounged about without any purpose, and at sundown the mobs dispersed like flocks of birds in their desire to rise up early so that they could come running together to once again fall upon the magnificent dwellings and search out their contents. The emperor gathered together his kinsmen and veteran troops and dispatched them early in the morning to attack John. Not even through the early dawn was the City's throng content to remain at rest; most were anxious to band together about the tyrant at the first break of day to assist him in his task and to fight against the imperial troops in many ways.

One group boarded ships and put in at the Monastery of Hodegoi, where they came to grips with the emperor's bodyguards; no armed men were able to pass through the center of the City. In the theater, they clashed abruptly with John's partisans, whom they dispersed easily, and with the greatest of ease they attacked and killed John, inflicting blows all over his body as if he were a fatted beast. His severed head was first brought to the emperor, and then, still grinning horribly and spurting out blood, it was suspended from the arch of the agora in full view of the public. The remainder of his body was lifted onto a bier and set out in the open at the southern gate of the Blachernai palace. From below the palatial suite of rooms that overlooked the gate, the emperor could be seen looking down upon the corpse swollen larger than a mammoth bull, taking delight in the spectacle and exulting in his achievement. Afterwards, the body was removed and exposed as food for dogs and birds, an act deemed brutal and inhuman by all. John's fellow conspirators, who had been seized and subjected to torture in order to ascertain the names of their accomplices, were sent off to prison in chains.

Such things and the following as well, this emperor wrought. Delivering over six triremes to a certain man whose name was Constantine and surname Frangopoulos, he sent him to the Euxine Pontos, ostensibly to investigate the cargo of a certain ship which had shipwrecked some- where near Kerasous while navigating the Phasis River"" down to Byzantion; in actuality he was to attack the merchantmen that sailed down to the city of Aminsos and plunder their wares. According to the imperial command, as he made his way up the Euxine, he spared not a single ship but despoiled all merchantmen, as many as were making for Byzantion laden with wares, as well as those that had discharged their cargoes and were on their way back after taking on fresh merchandise. He returned two months later having. put certain merchants, whose monies he appropriated, to the sword; these he cast into the deep, and others he dismissed more naked than a pestle. The latter made their way into the City, where they appeared before the palace and entered the holy temples holding burning tapers. They entreated the emperor to help them recover the losses they had unjustly suffered, but once he had sold their merchandise and deposited the revenues in his treasury, they could not move him to compassion.

The Ikonion merchants applied for help to Rukn al-Din, who then dispatched envoys to the emperor and demanded the return of their monies; negotiations for a peace treaty were also undertaken at this time. Resting his hope on a lie and attempting to obscure the obvious, the emperor condemned Frangopoulos as having acted contrary to his wishes and renounced all the wicked acts that he had committed. When the accord was concluded [August 1200], Rukn al-Din received fifty minae of silver as compensation for the merchants' losses in addition to the annual tribute. Some days later, the emperor was caught red-handed conspiring against the life of Rukn al-Din: he induced a certain Assassin with pro- mises of a huge reward, foolishly, since this was a precarious friendship, and, handing him a letter written in red ink, sent him forth to kill Rukn al-Din. But the Assassin was taken captive, and when he disclosed the letter and the plot, the peace treaty was broken; as a result, the Turks once again carried out many attacks against the Eastern cities.""

A certain Michael, the self-willed, bastard son of John the sebastokrator, dispatched as the tax collector for the province of Mylassa, rebelled against the emperor [summer 1200]. Defeated in battle, he took flight and sought refuge with Rukn al-Din, who, because he hated the emperor, most gladly welcomed him. With Rukn al-Din's troops, Michael ravaged the cities along the Maeander in many ways, showing himself to be worse than the foreigners and a more pitiless murderer.

It was the Komnenos family that was the major cause of the destruction of the empire; because of their ambitions and their rebellions, she suffered the subjugation of provinces and cities and finally fell to her knees. These Komnenoi, who sojourned among the barbarian nations hostile to the Romans, were the utter ruin of their country, and whenever they attempted to seize and hold sway over our public affairs, they were the most inept, unfit, and stupid of men.

In response to Michael's rebellion, Alexios marched out to the eastern provinces in the leaf-shedding month [November 1200]. On his return, he stopped off at the Pythia to bathe in the hot waters. When he had had enough of bathing tubs and bowls of wine, he thought to extend his voyage at sea, for the pleasures of land and sea competed before the emperor, each in its turn prevailing and winning the splendid crown of victory. Alexios then boarded a flagship, which sailed straightway through the nearby islets that gird Constantinople and around the Astakenos Gulf. At this time, a violent storm blew up suddenly, swelling the waves. The ship was lifted upright, bow over stern, and all but sank as water poured in from both sides. The sailors, thrown into confusion, dripped with sweat, and the passengers shouted for help and invoked God, and there was the sound of wailing and piercing screams. With the emperor were sailing all of his friends, both male and female; the desire of all was only to set foot on dry land. At great risk, the ship managed to round Prinkipos and, when the waves subsided, sailed down to Chalcedon. There the company recovered from their vertigo, and spitting out the brine and consigning to the deep of oblivion the vicissitudes and terrors of their plight, they crossed over to the Great Palace, celebrating horse races and entertaining the populace with spectacles.

At the conclusion of these events, the emperor wished to go directly to Blachernai, but because the season was unsuitable (for the emperors up to our times scrutinize the position of the stars before they take a single step), he remained in the Great Palace through the first week of Lent [11-18 February 1201] against his wishes. Since the sixth day [17 February] was not unpropitious for a change of residence, especially if he departed in the morning twilight, he decided to arrive at Blachernai in the dark, before the sun had begun to cast its rays. The trireme rode at anchor off the shore of the palace, and all the emperor's kinsmen assembled at his side with lights to sail in company with him. Now God demonstrated that he is the Lord of seasons and years and that he guides the steps of some or trips them up: the floor before the emperor's bed collapsed without visible cause and opened into a yawning chasm. Contrary to all expectations, the emperor was delivered from the danger, but one of his sons-in-law, Alexios Palaiologos, and many others fell through the opening and suffered grievous injury to their legs. A certain eunuch was killed as he fell to the very bottom of the gaping hole. What were the emperor's thoughts about these events, I have no way of knowing. What occurred immediately afterwards [spring 1201], I will now record.

This emperor's third daughter was named Evdokia. While her father wandered among the Ismaelites and roamed Palestine to escape Andronikos, Isaakios, her father's brother, gave her in marriage [1185-87] to one of the sons of Stefan Nemanja, the ruler of the Serbs. Stefan Nemanja remained in power for only a short time and then ascended Mount Papykios and embraced monastic life [1196]; his son Stefan presented Evdokia' as joint heir to the paternal satrapy and succeeded after many years in fathering children with her.

But time, the transformer and perpetual engenderer of dissimilarities, sundered them from their former unity and like-mindedness and did not allow their oneness to remain unsullied until their last breath, that which prudent couples deem to be the fullness of human happiness. Stefan accused his wife of itching from scabby incontinence, while she charged him with being drunk from the appearance of the morning star, with not drinking water from his own water jars, and with gorging himself on bread eaten in secret. As the dissension continued to grow apace in this manner, Stefan conceived a monstrous and most barbarous action which he pursued with a vengeance; fabricating the story (or he may have been telling the truth) that Evdokia was caught in the act of adultery, he stripped her of her woman's robe, leaving her with only her undergarment, which was cut round about so that it barely covered her private parts and dismissed her thus in disgrace to go forth as a wanton [after June 1198].

Vukan, Stefan's brother, opposed this indecent, relentless, and excessively repellent act and reproached his brother for his inhuman behavior. He pleaded with him to temper his wrath in view of Evdokia's illustrious lineage and to take pity on himself lest he become notorious for his shameful deeds. But he could not deter Stefan from his unbending, im- placable resolve, and, deeming Evdokia worthy of a proper and safe return, he delivered her to an escort to conduct her to Dyrrachium in a fitting manner. When Evdokia's father learned what had happened, he dispatched a two-headed throne, necklaces, and splendid imperial garments and welcomed his daughter.

Nemanja's sons did not continue to the end in brotherly love; warring against one another, they joined the chorus of others who, as we stated but a short while ago, ignore nature because of their lust for power and the stupidity of their ways. The victorious Vukan expelled Stefan from both throne and country [April 1202 to summer 1203]. When fratricide spread as a pattern, model, and general law from the queen of cities to the far corners of the earth, not only Turks, Russians, Serbs, and after- wards Hungarians [1203] but also the remaining rulers of barbarian nations filled their countries with seditions and murders, drawing their swords against their own kinsmen.

During these years [1201-2], Ioannitsa marched out from Mysia with a very large and well-armed force; laying siege to Konstantia, he easily took this eminent city in the district of the Rhodope. He razed the city's walls and departed to encamp near Varna, which he besieged fiercely on the sixth day of the Lord's Passions [23 March 1201]. The majority of the defenders were mighty warriors, and these, aided by Latin troops, defended the city tenaciously. In response, loannitsa constructed a four-sided siege engine as long as the fosse's width and as high as the city's wall and set it on wheels, positioning it next to the fosse. Later, when it was overturned, it spanned both sides; thus, loannitsa's troops used one and the same siege engine both as a bridge across the fosse and as a scaling ladder that reached the city's height. In this way, Varna was taken in three days. loannitsa neither respected the solemnity of the day (for it was the most blessed Sabbath on which Christ slept in the tomb) nor reverenced the name of Christian, to which he only paid lip service. Driven by bloodthirsty demons, he pushed all those he took captive alive into the fosse, and, filling it level with earth, he made of it a common burial place. When he had demolished the walls of the city, he returned to Mysia, having honored the first and chief day of the week with such offerings to the dead and most loathsome rites.

At the same time, the following events were taking their course. The protostrator Manuel Kamytzes, who had long been confined in prison in Mysia [since 1200], begged his cousin the emperor to pay his ransom out of his own substance. He was a captive of the barbarians and should not be overlooked as though he were a criminal. But he could not sway the emperor in his letters. Despairing, he appealed to his son-in-law Chrysos and beseeched him to ransom him. Once his petitions were consummated, he left Mysia for Prosakos. He did not desist once he arrived there from importuning the emperor to pay Chrysos the ransom money, which amounted to two hundred pounds of gold, contending that much more had been confiscated, in addition to the silver and gold vessels, the silken yarn, and splendid garments about which he had preened himself as the richest of men. Alexios placed his relationship with the protostrator on one scale of balance and his wealth on the other and weighed both; he found that the second was by far the heavier in the fall of the scale pan; whence he paid no heed whatsoever to Kamytzes' petitions.

In desperation Kamytzes, together with Chrysos, decided to attack the Roman themes that bordered Prosakos. They conquered Pelagonia with ease and effortlessly subdued Prilep, and they meddled in the affairs of the following: they incited revolts in distant places; they penetrated Thessalian Tempe and took possession of the plains; they created disturbances in Hellas and made the Peloponnesos unstable.

Then a second rebel rose up like the mythical giant from among the Sown-men: a certain John whose surname was Spyridonakis, a Cypriot by race, plain in appearance and of average height, squint-eyed, a craftsman by trade, a rustic in station, and this emperor's attendant, who, thanks to unreasonable promotions and preferments, was appointed keeper of the private fisc. Afterwards appointed governor of Smolena, he observed the meanness of mind and brazenness of him who sent him; elated by the security of his province, he became the emperor's despair, a second obstacle, a Satan, a thorn, and an unforeseen circumstance of the worst kind.

The emperor was afflicted by a third evil, the chronic disease which had spread to the joints of his body, and thus, like Epimetheus, he was dangerously exposed to both enemies. He jumped about and thrashed his legs as though he were held fast by the throat, all this because he had not ransomed his cousin and, to his own reproach, had installed Spyridonakis, that worthless scoundrel among men, as governor of so many strongly fortified cities.

Dividing the assembled troops into two forces, he committed one to the command of his son-in-law, Alexios Palaiologos, whom he sent in pursuit of the manikin Spyridonakis, and dispatched the other to John Ionopolites to oppose the protostrator. The emperor's valiant brother-in-law, Alexios, prevailed against Spyridonakis with little trouble and forced the pigmy-like humunculus to flee to Mysia. The protostrator's rebellion continued for some time, but it also had an auspicious conclusion. With guile, the emperor resorted to various ruses in dealing with Chrysos; in particular, he sent from Byzantion Theodora, his daughter's daughter, whom he had betrothed to Ivanko, and gave her in marriage to Chrysos. By such tricks he regained Pelagonia and Prilep and caused Kamytzes to withdraw from Thessaly, partly because he was defeated in battle and partly because he decided to flee. Finally, Alexios forced him out of Stanon, to which he had escaped as an impregnable refuge. Aglow with such successes, he imagined that he would be invincible for a long time to come and thus was free to remain at home, and he returned to Byzantion. At this time [spring 1202], he took Strummitsa, using guile to surround Chrysos, and concluded a peace treaty with Ioannitsa.

Up to now, the course of our history has been smooth and easily traversed, but from this point on I do not know how to continue. What judgment is reasonable for him who must relate in detail the common calamities which this queen of cities endured during the reign of the terrestrial angels? I would that I might worthily and fully recount the most oppressive and grievous of all evils. But, since this is impossible, I shall abbreviate the narration in the hope that it will be of greater profit to posterity because moderation has been exercised in reporting the suf- ferings, thereby mitigating excessive grief.

Emperor Alexios had deposed his brother Isaakios from the throne; it is necessary that we do not lose sight of his incarceration altogether. Alexios, unmindful of the indelible disasters suffered by the masses (nor does Vengeance sleep forever, but takes delight in the chronic changes [in government] and eagerly pursues those who perform lawless acts, pounc- ing swiftly and noiselessly), provided his brother, who was confined at the Double Column which stands on the shore near the straits, with a comfortable existence, and no one was denounced for sailing across to him. Anyone who wished to do so, and especially from among the race of the Latins, sailed up to Issakios. Made privy to secret designs aimed at opposing and overthrowing Alexios, he posted letters to his daughter Irene, who shared the marriage bed with Philip, king of the Germans at that time, and urged that he be avenged as a father; and replies winged their way thence, advising him what to do.

Later, the emperor released Issakios's son, Alexios, from prison and allowed him to move about freely. When he was about to march out against the protostrator and had taken up quarters at Damokraneia'43a [c. September 1201], he took Alexios along as a companion in travel. The latter, presumably following his father's instructions, negotiated his escape with a certain Pisan, the captain of a huge round ship. The Pisan waited for the opportune moment to put out to sea without delay, concealing his tracks in the teeming waves. As soon as the weather was favorable for sailing, the ship unfurled her sails and, borne along by a fair breeze, ran ashore on Avlonia on the Hellespont, where its small boat put in at Athyras to pick up Alexios. To escape detection, it was filled with a load of sand to be used as ballast in the ship, which supposedly had been emptied of its wares. Alexios arrived from Damokraneia, entered the boat, and was transferred to the ship. When his escape became known, the emperor dispatched men to seach through the ship, but they failed to capture Alexios; by clipping his hair round about and donning Latin raiment, he was able to mingle with the throng and escape the notice of his pursuers. When he reached Sicily, his presence was made known to his sister, who dispatched a considerable bodyguard. She embraced her brother and beseeched her husband Philip to do his utmost to succor her father, who had been deprived of both sight and power by his kinsmen, and to help her brother, who was homeless and without a country and wandered about like the planets, taking with him no more than his body.

Later, the emperor released Issakios's son, Alexios, from prison and allowed him to move about freely. When he was about to march out against the protostrator and had taken up quarters at Damokraneia'43a [c. September 1201], he took Alexios along as a companion in travel. The latter, presumably following his father's instructions, negotiated his escape with a certain Pisan, the captain of a huge round ship. The Pisan waited for the opportune moment to put out to sea without delay, concealing his tracks in the teeming waves. As soon as the weather was favorable for sailing, the ship unfurled her sails and, borne along by a fair breeze, ran ashore on Avlonia on the Hellespont, where its small boat put in at Athyras to pick up Alexios. To escape detection, it was filled with a load of sand to be used as ballast in the ship, which supposedly had been emptied of its wares. Alexios arrived from Damokraneia, entered the boat, and was transferred to the ship. When his escape became known, the emperor dispatched men to seach through the ship, but they failed to capture Alexios; by clipping his hair round about and donning Latin raiment, he was able to mingle with the throng and escape the notice of his pursuers. When he reached Sicily, his presence was made known to his sister, who dispatched a considerable bodyguard. She embraced her brother and beseeched her husband Philip to do his utmost to succor her father, who had been deprived of both sight and power by his kinsmen, and to help her brother, who was homeless and without a country and wandered about like the planets, taking with him no more than his body.

Besides these events, others come to mind which must not be overlooked. The Angelos brothers were guilty of poor administration of state affairs in other ways as well, as we have already recounted ; particularly obsessed with the love of money, they were not content with enriching themselves from legitimate sources of revenue, nor did they hold on to the wealth they amassed but poured it out with both hands on the excessive indulgence of the body and costly ornamentation. Moreover, they enriched courtesans and kinsmen who were utterly useless to the state. Not only did they glean and fleece the Roman cities, inventing novel taxes, but they also taxed the members of the Latin nations in their midst. Often disregarding the treaties made with the Venetians, they mulcted them of monies, levied taxes on their ships, and raised the Pisans against them. One could see both nations joining in battle, at times inside the City, and at times on the open sea, with one side prevailing and then the other, each taking turns pursuing the other and being plundered.

The Venetians, who recalled their ancient treaties with the Romans, could not endure seeing the friendship pledged to them being awarded to the Pisans. It was evident that they were gradually turning against the Romans, waiting for the opportune moment to even the score. Moreover, Alexios, in his niggardliness, refused to give them the two hundred pounds of gold still owed them from the fifteen hundred pounds which Emperor Manuel had agreed to repay the Venetians for the monies he had confiscated when he had arrested them.

The doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, was not the least of horrors; a man maimed in sight and along in years, a creature most treacherous and extremely jealous of the Romans, a sly cheat who called himself wiser than the wise and madly thirsting after glory as no other, he preferred death to allowing the Romans to escape the penalty for their insulting treatment of his nation. And all the while he pondered on how many evils the Venetians associated with the rule of the Angelos brothers [Isaakios II and Alexios III], and of Andronikos before them, and prior to him of Manuel, who held sway over the Roman empire. Realizing that should he work some treachery against the Romans with his fellow countrymen alone he would bring disaster down upon his own head, he schemed to include other accomplices, to share his secret designs with those whom he knew nursed an implacable hatred against the Romans and who looked with an envious and avaricious eye on their goods. `0 The opportunity arose as if by chance when certain wellborn toparchs were eager to set out for Palestine; he met with them to arrange a joint action and won them over as confederates in the military operation against the Romans. These were Marquis Boniface of Montferrat, Count Baldwin of Flanders, Count Hugh of Saint Pol, Count Louis of Blois,'441 and many other bold warriors who were as tall as their lances were long.

Within three full years [actually April 1201-July 1202] one hundred and ten horse-carrying dromons and sixty long ships were built in Venice, and more than seventy huge round ships were assembled (one much larger in size than the others was called Kosmos [Mundus]). One thou- sand cavalry clad in full armor and thirty thousand bucklers divided mostly into heavy-armed foot soldiers, especially those called crossbowmen, were commanded to board them.

Once the fleet was ready to put out to sea, evil was heaped upon evil, and wave after wave rolled in upon the Romans, for Alexios, the son of Isaakios Angelos, was supplied with letters from the pope of elder Rome [Innocent III]` and Philip, king of Germany, that pledged their profound gratitude to these piratical gangs if they would welcome Alexios and restore him to his paternal throne. Later, when Alexios appeared, and most willingly, before the fleet, his presence was thought to provide not only an opportune camouflage for sailing out to plunder the Romans but also a specious reason for sating the Venetians' avaricious and money-loving temperament. As they were all-cunning in their ways and troublemakers, they laid hold of Alexios, who was juvenile in mind rather than in age, and prevailed upon him to agree under oath to demands which were impossible to fulfill. The lad consented to their requests for seas of money and, in addition, agreed to assist them against the Saracens with heavy-armed Roman troops and fifty triremes. What was even worse and most reprehensible, he abjured his faith and embraced that of the Latins and agreed to the innovation of the papal privileges and to the altering of the ancient customs of the Romans.

Releasing the stern cables [2-8 October 1202], the fleet sailed down to Zara and laid siege to the city [11-24 November 1202] for supposedly violating ancient treaties, following the instructions of Dandolo, doge of Venice. The Roman emperor Alexios, who had received information over a long period of time as to the movements of the Latins, was disposed to do nothing better on behalf of the Romans; his excessive slothfulness was equal to his stupidity in neglecting what was necessary for the common welfare. When it was proposed that he make provisions for an abundance of weapons, undertake the preparation of suitable war engines, and, above all, begin the construction of warships, it was as though his advisors were talking to a corpse. He indulged in after-dinner repartee and in willful neglect of the reports on the Latins; he busied himself with building lavish bathhouses, leveling hills to plant vineyards, and filling in ravines, wasting his time in these and other such activities. Those who wanted to cut timber for ships were threatened with the gravest danger by the eunuchs who guarded the thickly wooded mountains, that were re- served for the imperial hunts, as if they were sacred groves, gardens, so to speak, planted by God. And instead of rebuking these foolish men, the emperor, taken in by their prattle, gave his approval.

After the Latins had conquered Zara, they landed at Epidamnos, and their fellow passenger Alexios was proclaimed emperor by the Epidamnites. When [Emperor] Alexios was convinced of the certainty of the report of these events, he was like the proverbial angler, who, on being smitten, recovered his senses.1448 Accordingly, he began to repair the rotting and worm-eaten small skiffs, barely twenty in number, and making the rounds of the City's walls, he ordered the dwellings outside pulled down.

The Venetian fleet set out from Epidamnos and put in at Kerkyra, where they delayed their voyage for twenty days [4-24 May 1203]. When they realized that the citadel was unassailable, they unfurled their sails and made for Constantinople, for the Westerners had long known that the Roman emperors concerned themselves with nothing else but carousing and drunkenness with making Byzantis another Sybaris celebrated for its voluptuousness.'45. After an exceptionally fair voyage (for the breezes out of the deep, ever gentle and swelling the sails, wafted their ships on their way), they appeared before the City while scarcely anyone took notice. They put in at Chalcedon (which lies on the opposite side of the straits from Peraia, to the east and a little below the Double Column); first came the transports propelled with oars, and shortly after- wards the warships arrived under sail and rode at anchor at a distance beyond an arrow's shot from the land. The dromons touched at Skoutarion.