t

t

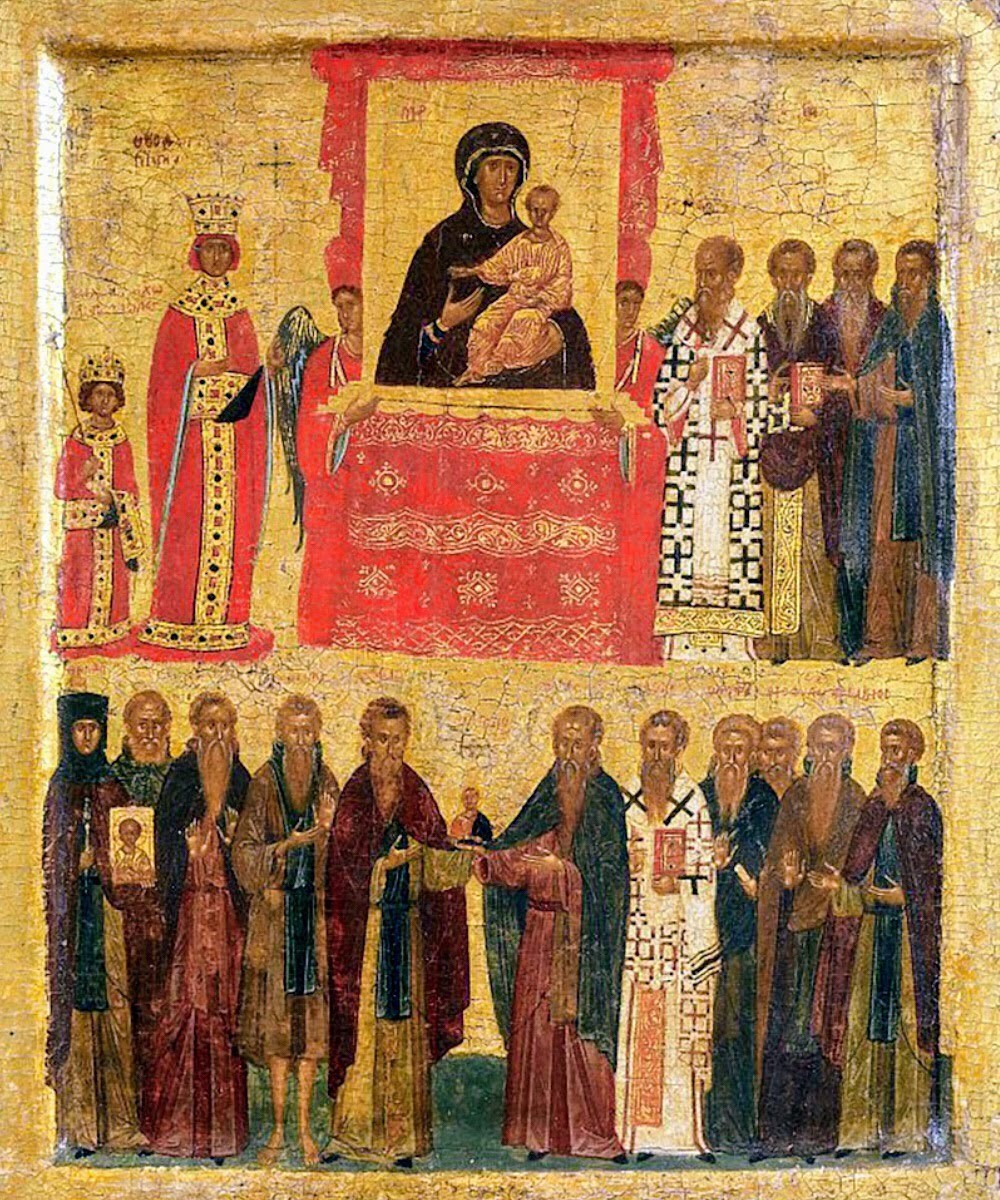

The original church was built by the Empress Pulcheria around 450 in a private area of the palace that was an imperial spa with gardens, villas and baths nearby. The shrine was rebuilt or expanded by Michael III around 850. The icon of the Theotokos Hodegetria was one of the most popular images of the Virgin and Child in Constantinople and was copied all over the Orthodox world. It was believed that the icon had been painted by Saint Luke and was sent to Pulcheria by her sister-in-law Athenais-Eudokia in the middle of the fifth century. Eudokia had been in Jerusalem from 438 until her death in 453.

The original church was built by the Empress Pulcheria around 450 in a private area of the palace that was an imperial spa with gardens, villas and baths nearby. The shrine was rebuilt or expanded by Michael III around 850. The icon of the Theotokos Hodegetria was one of the most popular images of the Virgin and Child in Constantinople and was copied all over the Orthodox world. It was believed that the icon had been painted by Saint Luke and was sent to Pulcheria by her sister-in-law Athenais-Eudokia in the middle of the fifth century. Eudokia had been in Jerusalem from 438 until her death in 453.

The monastery was small but had elegant architecture, including a curved columned porch and five multi-apsed domed chamber 85 feet across where the the sick were bathed in a huge two-pooled 25-sided marble bath. The water came from a sacred well - hagiasma - which was located to the east and channeled into the building. The church was three-aisled, had a nave with galleries and stood on a platform or terrace. It was described as being the size of a big house. It might have had a dome. Besides the famous icon the monastery also housed drops of the Virgin's milk, her spindle as well as diapers of Christ and drops of his blood. From the 10th until the 15th centuries the monastery was the headquarters of the patriarchs of Antioch. The patriarch was evicted by Mehmet II in 1456.

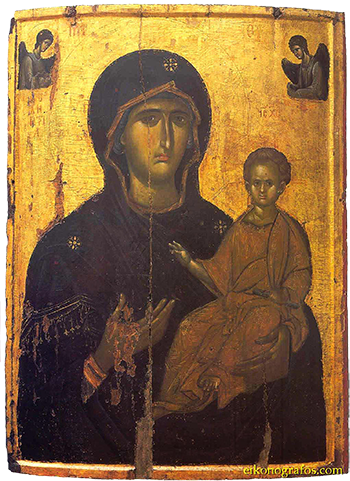

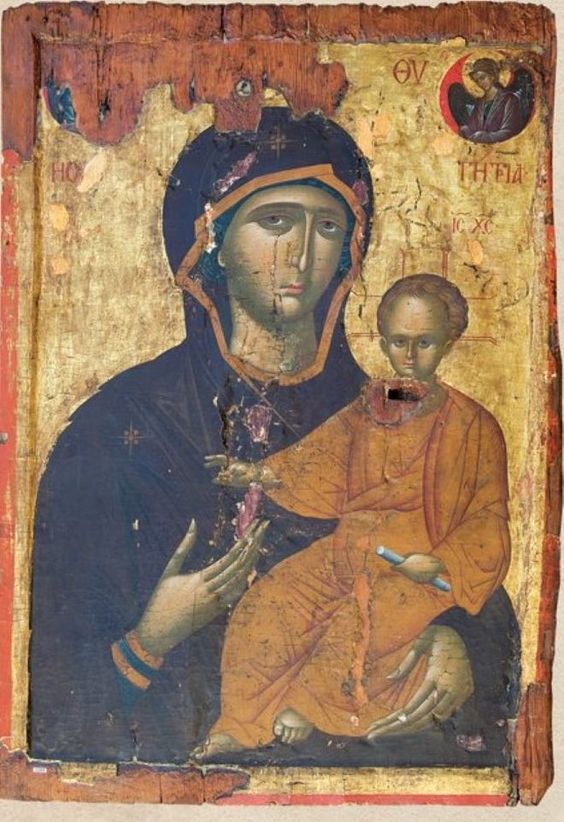

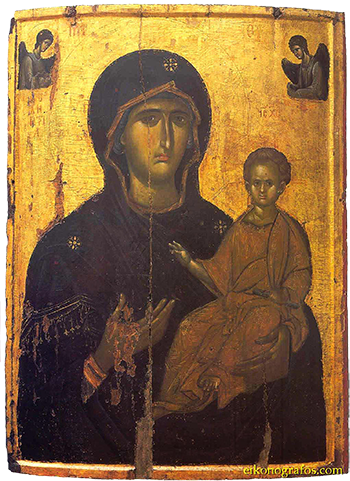

The icon was described by the Spanish traveler Clavijo as being six palms tall and square. That means it was around 40-45 inches square. It was painted on the reverse with an icon of the Crucifixion. The icon showed Mary dressed in a purple maphorion and dress of the same color. The maphorion was bordered in gold and had a embroidered hanging fringe. There are stars on the shoulder and head covering the Virgin. She wears a silk cap over her hair. Christ is wearing a golden red garment of two parts. It is covered all over in golden highlights. He holds a white scroll in his left hand lengthwise. The right hand is extended out flat in blessing over the hand of the Virgin. Both figures are hierarchically drawn with strong contours. They are sitting in a rigid upright posture. On the left you can see Saint Luke painting the icon.

The icon was described by the Spanish traveler Clavijo as being six palms tall and square. That means it was around 40-45 inches square. It was painted on the reverse with an icon of the Crucifixion. The icon showed Mary dressed in a purple maphorion and dress of the same color. The maphorion was bordered in gold and had a embroidered hanging fringe. There are stars on the shoulder and head covering the Virgin. She wears a silk cap over her hair. Christ is wearing a golden red garment of two parts. It is covered all over in golden highlights. He holds a white scroll in his left hand lengthwise. The right hand is extended out flat in blessing over the hand of the Virgin. Both figures are hierarchically drawn with strong contours. They are sitting in a rigid upright posture. On the left you can see Saint Luke painting the icon.

The hand of the Virgin is pointing towards her Son and this if the source of the name "Hodegetria" which means "director" or "indicator of the way" to Christ. There is some uncertainty about where this name came from. The icon was housed in a holy chamber attached to the Monastery of the Hodegon. There was a two-tiered holy well and fountain outside the monastery that was supposed to heal people. The monks were called the "directors" of people to the well and the name of their monastery came from that function, not the icon. Over time the monastery and icon had the same name. Being seen as a "directoress" came to the icon later. The miraculous Holy Well of the monastery was just as important to the people of Constantinople as the icon. Ruins of the Holy Well have been discovered and it seems from their size and shape that people were able to immerse and wash themselves in the water. It was a beautiful columned shrine of marble, the Holy Well and monastery were located between Saint George of the Mangana and the modern Gulhane hospital. The complex was not that far from Hagia Sophia and the Great Palace. The monastery was built by the Augusta Pulcheria and its location would have been convenient for her being near her palace.

It is obvious that the original icon was not painted by Saint Luke and this pious myth was invented by the people who "discovered" it around the year 400. The designation "Theotokos" - God-bearer - was commonly used by Christians as early as the second century. A prayer to the Theotokos on papyrus has been found in Egypt from that period. The earliest painting of Mary dates from around 240 and was discovered in the ruins of a church in Dura Europos.

If Saint Luke had painted portraits of Mary and Jesus they would have to have been done somewhere around Nazareth 300 years before and their preservation would had been a great miracle. In the fourth and early fifth centuries there were many pilgrims searching throughout Palestine for relics of Christ and Mary. At this same time the famous maphorion of the Virgin as discovered there and brought to Constantinople by two aristocratic brothers who stole it from a Jewish woman who told them her family had it in their position since the Virgin had lived in Nazareth. Imperial agents brought a number of icons that were supposedly painted by Saint Luke to Pulcheria and she believed they were genuine. Pulcheria built three shrines in Constantinople to house them. The first one went to the new church of Mary of the Blachernae, the second went to the church of the Chalkoprateia and the third went to the Hodegetria church and monastery.

If Saint Luke had painted portraits of Mary and Jesus they would have to have been done somewhere around Nazareth 300 years before and their preservation would had been a great miracle. In the fourth and early fifth centuries there were many pilgrims searching throughout Palestine for relics of Christ and Mary. At this same time the famous maphorion of the Virgin as discovered there and brought to Constantinople by two aristocratic brothers who stole it from a Jewish woman who told them her family had it in their position since the Virgin had lived in Nazareth. Imperial agents brought a number of icons that were supposedly painted by Saint Luke to Pulcheria and she believed they were genuine. Pulcheria built three shrines in Constantinople to house them. The first one went to the new church of Mary of the Blachernae, the second went to the church of the Chalkoprateia and the third went to the Hodegetria church and monastery.

If the original icon was painted in the fifth or sixth centuries in Palestine it would have been a painted in wax encaustics. In this technique colors are mixed in melted wax which is then applied to a gesso and wood panel with hot spatulas. lter Byzantine artists never worked in this technique - they only painted in egg tempera. Both media were painted on a wood panels and different kinds of wood were used. Some soft woods, like pine and linden are light while other harder woods like oak and cypress were heavier. It was best if you could find good panel wood nearby, but the best wood could be shipped hundreds of miles from its origin. Constantinople was fortunate in the fact that there was plenty of good wood close at hand. Because of the large size of the icon several boards would have been glued together. The panel would have been hollowed out leaving a narrow band around the edge. Sometimes a layer of cloth, usually linen, was glued to the panel before many coats of white gesso were applied to the surface and it was smoothed. The gesso was a mixture of white ground and animal glue that had been heated before it was applied. In workshops panels were made by specialized workers and stocks were built up in different sizes. They were allowed to set for a period of time to watch for potential cracks or splits. Icon panels can be greatly effected by changes in humidity - waiting for up to a year was sometimes required. After examining them the artist would select the one they wanted to paint.

The artist would apply a drawing to the panel of the subject of his icon in paint or by using a stylus to scratch the outlines into the gesso. If gilding was involved it was applied using a size and the surface was burnished to make it shine. Colors were now selected for the painting. Pigments could come from nearby sources and be inexpensive like earth tones. Rare and beautiful colors, like blue made from crushed lapis lazuli could have come from thousands of miles away. Pigments were made from natural minerals and also from some exotic things like crushed beetles. Some colors lasted for hundreds of years and others, like rose madder, faded or changed over time. There was a very beautiful blue azure that was made of crushed glass. Some colors like were difficult to use - like ultramarine blue (from lapis) and alizarin crimson - because they were hard to get 'wet' and mix into the medium you were using. Lapis had to be ground down to the finest power and worked for hours to get it to wet in a paste. Apprentices were taught to prepare pigments for the artists. The bigger the painting the more expensive the pigments could be. Lapis color for one big painting could cost the equivalent of several hundred dollars today. Sometimes artists worked independently and could not afford expensive pigments. It was possible to paint an icon like the Hodegetria entirely in inexpensive, easy to use colors. Lapis blue could be simulated by painting a thin cheaper blue in a glaze over black. Painters could also save money by using silver leaf rather than expensive gold for their backgrounds. They then applied a coating in translucent orange shellac over the silver. Many of the icons in Sinai are gilded in this way.

The artist would apply a drawing to the panel of the subject of his icon in paint or by using a stylus to scratch the outlines into the gesso. If gilding was involved it was applied using a size and the surface was burnished to make it shine. Colors were now selected for the painting. Pigments could come from nearby sources and be inexpensive like earth tones. Rare and beautiful colors, like blue made from crushed lapis lazuli could have come from thousands of miles away. Pigments were made from natural minerals and also from some exotic things like crushed beetles. Some colors lasted for hundreds of years and others, like rose madder, faded or changed over time. There was a very beautiful blue azure that was made of crushed glass. Some colors like were difficult to use - like ultramarine blue (from lapis) and alizarin crimson - because they were hard to get 'wet' and mix into the medium you were using. Lapis had to be ground down to the finest power and worked for hours to get it to wet in a paste. Apprentices were taught to prepare pigments for the artists. The bigger the painting the more expensive the pigments could be. Lapis color for one big painting could cost the equivalent of several hundred dollars today. Sometimes artists worked independently and could not afford expensive pigments. It was possible to paint an icon like the Hodegetria entirely in inexpensive, easy to use colors. Lapis blue could be simulated by painting a thin cheaper blue in a glaze over black. Painters could also save money by using silver leaf rather than expensive gold for their backgrounds. They then applied a coating in translucent orange shellac over the silver. Many of the icons in Sinai are gilded in this way.

Workshops kept large quantities of dry pigments in storage for future use. They also generally made their own tools, like paint spatulas, brushes and compasses to draw halos. However in Constantinople pigments could also be purchased in specialized stores that sold them by weight. The rarest pigments were sold by the same shops that sold aromatics like frankincense and cinnamon. There were other stores that sold paper, brushes, and agate burnishers to polish gold. The best brushes were made of squirrel from Russia. Different tools were required for painting in egg tempera and wax encaustic.

We can see surviving examples of icons painted in encaustic paints from Sinai that date from a hundred years later. The famous mummy Roman portraits of Fayum are also painted in the same medium. The method involves the quick application of the colors which can be added in layers that fuse together as they are laid on. An artist working in encaustic painting has to move rapidly and requires expert skill in portraiture. The original background the icon would not have been gilded it would have contained some architectural setting. The figures would have had haloes. Over time the painting must have required retouching. Wood panels warp and crack. Had the panel been painted in the dry climate of Palestine when it was moved to seaside Constantinople it would have been subject to changing humidity, moisture and temperature changing from freezing in winter to hot in summer. Then there is the period of Iconoclasm when all icons like this one were destroyed. We are told that icons and relics were saved by Christians who hid them. The Hodegetria was said to have been hidden in a wall at the Pantokrator monastery along with a lamp that mysteriously burned continuously for over 100 years unattended. This is obviously not true, the myth confuses the time when the icon was in the possession of the Venetians during the Latin occupation when they kept it there.

If the icon was not saved it would have been replaced with a new one in the 9th century - after the restoration of icons. The Byzantines never doubted that the Hodegetria was the original one they thought had been painted by Saint Luke. Obviously we will never know since the icon was destroyed by Muslims in 1453.

The icon had a silver-gilt cover that was set with gemstones and pearls. The cover would have covered everything except for the figures of the Virgin and Child. When the cover was removed drawings were taken from the icon so it could be perfectly duplicated by artists over hundreds of years. Later artists created many variants of the icon, changing the position of the hands and softening the position of the figures. The hand of Christ in the original had always presented a problem for copyists, it should have been held in blessing higher up and directed at the viewer. In the original He seems to be blessing someone below and to the right side of the icon. Perhaps that indicates the way the icon was originally displayed. Maybe there was a painted figure of Pulcheria or some other figure on that size that Christ was blessing. Later versions change the clothing of Christ and the position of the hand and scroll. Most apparent are new versions with the Virgin turning her eyes away from the viewer of the icon to Christ and he turns His towards his mother.

One can easily identify the best and most accurate copies by the folds in the clothes of Christ and the position of the scroll. Some of the best copies of the Hodegetria are in Russia. Copies were commissioned or bought in Constantinople and sent there. This is why there are a number original Byzantine icons of the Hodegetria there. The Russians also created their own version of the icon which they called "of Smolensk", "Smolenskaya" which is virtually the same.

After the end of Iconoclasm, the Hodegetria icon played an important part in the daily life of the entire city of Constantinople. Once a week the icon was taken from the monastery in a great procession to other churches in the city. The procession involved thousands of people and went through the streets and forums of the city with people leaning out of windows to view and shout praises to the Virgin as she passed. The icon was proceeded by huge silver crosses on poles and men carrying large bowls and swaying censors of incense. Many people, men and women, carried branches of aromatic trees and boughs of fragrant roses that swayed in the breeze. Like nobles attending an empress the icon was proceeded and followed by other icons, banners and great silver flabellum on poles. It was protected by a two great red silk canopies that were supported by members of the special confraternity - who were dressed like angels - that were responsible for the protection of the icon. The icon was carried on a three-pronged stand that was strapped to the chest on the man carrying it. When then procession passed a church dedicated to Christ the icon of the Hodegetria bowed in honor of her Son.

On its route the icon stopped in churches along the way. During its weekly move the Hodegetria remained overnight in the Pantokrator monastery on Fridays and went from there to the imperial palace on Saturday before returning to its home. The icon was very important to John II Commenos. In his instructions regarding the icon at the Pantokrator he writes:

"However I wish the holy icon of my most pure Lady and Mother of God Hodegetria to be taken into the monastery on the days of our commemorations —that is, those for the most beloved wife of my majesty, for my majesty itself, for my most beloved son and basileus, Lord Alexios, if he will want to be buried with me — and while her holy icon is brought in, an ektenes should be made for us by all those who are following it and the kyrie eleison repeated thirty times. Then this holy icon should be set in the church of the Incorporeal near our tombs and on those nights vigils should be held by the monks and the clergy, and on the next day the divine liturgy should be celebrated while the holy icon is present, and after the dismissal an ektenes should again be made for us in the presence of all the assembled people, and they should receive when they leave fifty hyperpyra nomismata at each visit of the Mother of God. e division of the money should be as follows: six hyperpyra nomismata for the holy icon, twenty-four hyperpyra nomismata for the twelve koudai, two similar nomismata for the bearers and the other servants of the holy icon. The rest should be changed into hagiogeorgata nomismata and distributed to the banners."

It was also brought to the palace on the Thursday before Easter and stayed there until Easter Monday. There were special vigils before holidays in front of the icon when pilgrims were anointed with holy oil.

The icon was displayed in its own columned kiot of marble, gilded silver that was adorned with hanging glass lamps hanging in settings of gold and gemstones. Around the kiot were draped bright red silk curtains and the icon was protected by translucent jeweled veils of gold embroidered silk and fine linen that were made by the women of the city. Near the icon there was The scent of wax candles, lamps filed with aromatic oils and fragrant incense was combined with the unearthly chanting of singers and the prayers of priests and monks. It created a scene of divine theater which the Byzantines were masters at producing in their religious ceremonies. All of this went on continuously 24 hours a day when the icon was present here by the monks of the monastery.

The icon survived the destruction of the Fourth Crusade and the great fires that swept the city and the looting that followed the fall of the city to the crusaders in 1204. This region of the city, including many of the most famous churches, like Saint George of the Mangana, was not damaged by the fires and became a new center of pilgrimage. Some workshops and stores continued to operate here. For some reason the icon was in Hagia Sophia when the Latins took over. In 1206 the Venetians forcefully stole the icon from the Latin Patriarch, Tomaso Morosini, which was in Hagia Sophia, and removed it to the south church of the Pantokrator where they could control access to it in their headquarters. It is no surprise that the Venetian Quarter in Constantinople was not burned in the great fires that swept the city in 1204 which had been set by the crusaders to drive the urban population from the city in advance of their invasion. The icon stayed in the city when Greek rule was restored in 1261. We don't know why it had not been sent to Venice along with the treasures of the Pantokrator of Hagia Sophia that went to Saint Marks. The icon still had its original precious silver-gilt covering set with enamels, gems and pearls. The Hodegtria was taken from the Pantokrator to greet the Emperor Michael VIII in a festive procession when he entered the city after the 58 year occupation. His son and successor, Andronikos II, visited the monastery frequently to give thanks for his military victories in front of the icon.

After the recovery of the city the Paleologians made the monastery an Imperial mausoleum, with many members of the family buried there. There was also an important workshop producing manuscripts based in the monastery.

After 1261 when the icon was brought to the Blachernae Palace it was displayed in front of the chapel of the Theotokos Nicopoios on the main square. When the icon was ready to depart from the Hodegon the emperor would come down from his chambers and personally escort the icon to the main gate of Blachernae.

After 1204 there was special ceremony associated with the icon that took place in the market square in front of the monastery. Stephen of Novgorod, a Russian pilgrim who visited Constantinople, describes the ceremony in 1200:

"Since it was Tuesday we went from there to the procession of the icon of the holy Mother of God.? Luke the Evangelist painted this icon while looking at [Our] Lady the Virgin Mother of God herself while she was still alive. They bring this icon out every Tuesday. It is quite wonderful to see. All the people from the city congregate. The icon is very large and highly ornamented, and they sing a very beautiful chant in front of it, while all the people cry out with tears, “Kyrie eleison.” They place [the icon] on the shoulders of one man who is standing upright, and he stretches out his arms as if [being] crucified, and then they bind up his eyes. It is terrible to see how it pushes him this way and that around the monastery enclosure, and how forcefully it turns him about, for he does not understand where the icon is taking him. Then another takes over the same way, and then a third and a fourth take over that way, and they sing a long chant with the canonarchs while the people cry with tears, “Lord have mercy.” Two deacons carry the flabella in front of the icon, and others the canopy. A marvelous sight: [it takes] seven or eight people to lay [something] on the shoulders of one man, and by God’s will he walks as if unburdened."

In 1437 Pero Tafur, who was visiting the city just a few years before the fall, describes it in detail:

"The next day I went to the church of St. Mary, where the body of Constantine is buried. In this church is a picture of Our Lady the Virgin, made by St, Luke, and on the other side is Our Lord crucified. It is painted on stone, and with the frame and stand it weighs, they say, several hundredweight. So heavy is it as a whole that six men cannot lift it. Every Tuesday some twenty men come there, clad in long red linen draperies which cover the head like a stalking-dress. These men come of a special lineage, and by them alone can that office be filled. There is a great procession, and the men who are so clad go one by one to the picture, and he whom it is pleased with takes it up as easily as if it weighed only an ounce. The bearer then places it on his shoulder, and they go singing out of the church to a great square, where he who carries the picture walks with it from one end to the other, and fifty times round the square. By fixing one's eyes upon the picture, it appears to be raised high above the ground and completely transfigured. When it is set down again, another comes and takes it up and puts it likewise on his shoulder, and then another, and in that manner some four or five of them pass the day. There is a market in the square on that day, and a great crowd assembles, and the clergy. take cotton-wool and touch the picture and distribute it among the people who are there, and then, still in procession, they take it back to its place. While I was at Constantinople I did not miss a single day when this picture was exhibited, since it is certainly a great marvel."

The Spanish traveler, Ruy Gonzales de Clavijo, describes the ceremony in 1405:

"Further again in the city of Constantinople there is a very holy church called Santa Maria de la Dessetria [otherwise the Hodegetria]. It is but a small church where are established certain Canons, and these religious men eat no meat, neither do they drink any wine, they partake of nothing cooked with olive-oil, nor any flesh of fish in which there is blood. The main building of this church is most beautifully adorned with mosaic-work: and they keep here an icon representing the Blessed Virgin Mary, set in a fine carved frame, and the same it is said was drawn and painted with his very own hand by the glorious and blessed Saint Luke. This icon they reported to us has done, and does daily do, many miracles. The Greeks here profess great devotion to this icon: and keep the festival thereof very magnificently. The icon is painted on a wooden board, square in shape and six palms high by the like across. The board stands supported on two feet, and the painting itself is now covered over by a silver plate in which are encrusted numerous emeralds, sapphires, turquoises and great pearls with other precious stones. The icon is preserved for safety in an iron chest. Every Tuesday is its feast-day when a great concourse of folk assembles, clerics and lay persons who are of pious mind. These with many of such as are clerics from the other churches of the city, when they have said the Hours, piously take the icon out from this church and carry it to a court near by. As it goes forth it is found to be so heavy that it requires three or four men to carry it, using straps of leather, attached to cramping-irons, by which the frame must be supported. When it is thus brought forth it is set up in the middle of that court where all present make their prayers and devotions with sobbing and wailing. This being done there comes forth an old man, who prays before this image of Our Lady, and then he lifts up the icon and carries it off, as though it were of but a trifling weight, and all by himself he bears it in the procession that returns forthwith to the church. Indeed it is a miracle how one man can possibly thus lift so great a weight as is the burden of the frame. They say that to no others is it possible thus alone to lift and carry it save to this particular man [and his brothers]. But this man is of a family any of whom can do so, for it has pleased God to vouchsafe this power to them one and all. On certain feast-days of the year they carry this icon with great solemnities to Santa Sophia, thus to display it for the great devotion in which the people hold the same."

These two descriptions tell us about economic activity in the city that was happening in the last years of christian Constantinople in an area of the old Great Palace, which was in ruins at the time. The square were this took place may have been built into parts of it that still remained in use. One can expect the weekly festival was very important to the merchants of the square because it brought large crowds. The monks must have earned money from the rent of the shops and from fees assessed on people who operated temporary stalls there.

In May 1453 the icon was taken to the Chora Church, which was near to the walls, to protect Constantinople from the Turks. The citizens of the city were able to see over the walls into the camps of the Turks. They could see the slave dealers in the camps who were waiting for the final assault to behind so they could begin their work. One can imagine alarm families must have felt when they contemplated the fate of their children. Soon all of the people in the city would be either be dead or sold into slavery. All over the city you could hear the sound of cannons pounding on the walls and the diabolical sound of Turkish military music and drums. When they broke into the city one of the first churches to looted was the Chora. The Muslim Turks pulled the silver and jewels from the icon, split it into four parts and burned it. In the looting of the city all of the remaining treasures of art and culture, many of which were 1000 years old were destroyed. The only stuff that survived were mosaics and frescoes that were on walls and vaults. The Turks passed over anything that was not easy to get at. The most valuable things the city still possessed were its people sold as slaves or ransomed for money.

Below is the marble holy font from the Monastery of Theotokos ton Hodegon in the Mangana, November 1935. Below it is a plan of the building. The remains of the shrine were uncovered in 1923.

t

t

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints