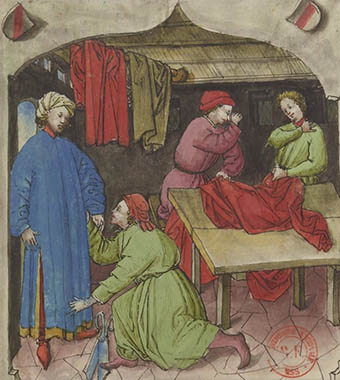

Byzantine workshops usually operated their own retail establishments. Men and women worked together in them. Most shops would hold around 10 people. Many workshops were family operations with several generations working under the same roof. Family workers were unregulated. More men were weavers than women, but weaving was a occupation that was totally open to women. Some weavers worked privately and sold their work to wholesalers. This work was done in standard sizes and resold in bundles for the domestic and international markets in various grades and colors. Wholesalers bought it door-to-door by agents, in public places - like the streets and forums - or in special cloth markets.

Many workshops were family operations with several generations working under the same roof. Family workers were unregulated. More men were weavers than women, but weaving was a occupation that was totally open to women. Some weavers worked privately and sold their work to wholesalers. This work was done in standard sizes and resold in bundles for the domestic and international markets in various grades and colors. Wholesalers bought it door-to-door by agents, in public places - like the streets and forums - or in special cloth markets. Clothing could be made in specialized workshops or at home in informal family operations. The Imperial workshops were not able to supply all of the needs of the government and the authorities bought ready-made clothing on the open market from private producers. Clothing was made in many types of fabrics like wool, linen and silk and combinations of fibers. Domestic consumption was the primary focus of makers of clothes in Constantinople, requiring tens of thousands of new clothes every year.

Clothing could be made in specialized workshops or at home in informal family operations. The Imperial workshops were not able to supply all of the needs of the government and the authorities bought ready-made clothing on the open market from private producers. Clothing was made in many types of fabrics like wool, linen and silk and combinations of fibers. Domestic consumption was the primary focus of makers of clothes in Constantinople, requiring tens of thousands of new clothes every year. Wholesale buyers of ready-made clothes not only sold to consumers in Constantinople, they also retailed them in local fairs and markets, Like the great fair of Thessalonica were most of the trade was in clothes. In the 12th century this trade expanded rapidly and was spread by a big increase in maritime shipping between ports in Greece and the Aegean Sea. This was one reason for the expansion of silk weavers to places like Thebes and the Morea.

Wholesale buyers of ready-made clothes not only sold to consumers in Constantinople, they also retailed them in local fairs and markets, Like the great fair of Thessalonica were most of the trade was in clothes. In the 12th century this trade expanded rapidly and was spread by a big increase in maritime shipping between ports in Greece and the Aegean Sea. This was one reason for the expansion of silk weavers to places like Thebes and the Morea.

Dress in Byzantium

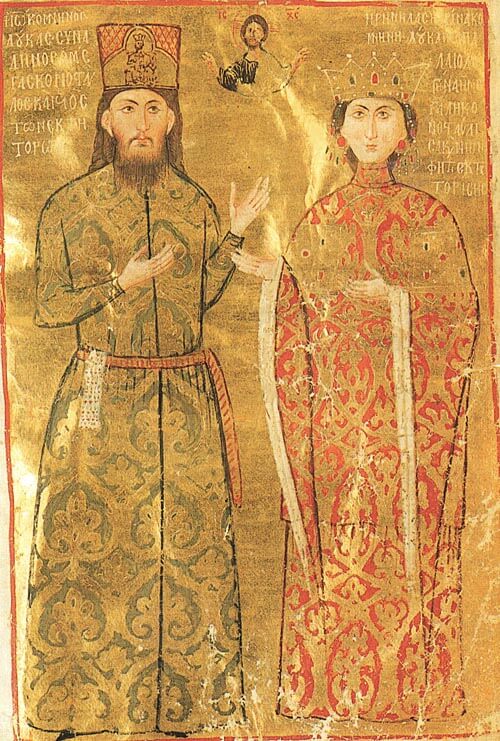

This is Constantine with his wife Eirene Raoulaina on the left. Although this is a copy, it is an actual family portrait from a set of 12 in the Lincoln College Typikon. Constantine was born in 1261 and died in 1306. This image depicts him when he was in his thirties. It was customary for people to give gifts of portraits like this to members of the Imperial family, especially the Emperor and his wife. Members of the Imperial family also commissioned paintings like this one and gave them to each other. They were collected in books like photo albums and were often accompanied by poetic epigrams praising the subjects that were especially commissioned by the donor as a part of the gift. Small-scale Imperial portraits on parchment and wood panels like were displayed around the city in churches, palaces and other public places.

This is Constantine with his wife Eirene Raoulaina on the left. Although this is a copy, it is an actual family portrait from a set of 12 in the Lincoln College Typikon. Constantine was born in 1261 and died in 1306. This image depicts him when he was in his thirties. It was customary for people to give gifts of portraits like this to members of the Imperial family, especially the Emperor and his wife. Members of the Imperial family also commissioned paintings like this one and gave them to each other. They were collected in books like photo albums and were often accompanied by poetic epigrams praising the subjects that were especially commissioned by the donor as a part of the gift. Small-scale Imperial portraits on parchment and wood panels like were displayed around the city in churches, palaces and other public places.

The first thing to note is that both of these outfits are cut and tailored to fit the wearer and are real clothes. This emphasis on the fit of a garment, large scale patterns and multiple items made of the same color and fabric, are things we see in late Byzantine clothes. Note the tight neckline on Eirene's dress and Constantine's sleeves to see the tight tailoring.

Constantine is wearing a tall red-silk hat - heavily embroidered with an enthroned image of his brother Andronicus, who was Emperor at the time, a kaftan - kabbadia - in heavy woven silk with tight sleeves, a red gold sash belt (weighted on the end to hang down properly) and an jeweled purse. There would have been a standing image of his brother on the back of his hat. His kaftan is an opulent silk brocade with a large bold pattern. The kaftan would have been lined.

A man like Constantine would have dozens of different types of splendid robes in different colors and patterns made for specific occasions and uses. As members of the Imperial court he and Eirene would have changed their dress many times a day, based on their activities. Writing of Emperor Isaac II Angelos’ passion for luxury, and comparing his appearance in the palace to a young bridegroom, "brilliant as the rising sun", the Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates tells us that Isaac never showed himself twice in the same costume. The Emperor Alexius Comnenus gave the Georgian Gregory Pakourianos articles of his own clothing that he had worn in honor of Gregory's victory over the Pechenegs. Gregory proudly left these items of clothing to his heirs in his will, that's how we know about them.

Men and women rode horses - Byzantine women rode astride like men. The Imperial ceremonial in the last 200 years involved more riding and fewer processions. The Emperor (and even the Empress!) was expected to be seen in public on horseback riding in and out of the palace grounds and around the city. You could get quite close to them.

In 1437 the Spanish historian and traveler Pero Tafur wrote about the hunt he went on with the Byzantine Emperor and his wife, Maria:

"The Empress rides astride, with two stirrups, and when she desires to mount, two lords hold up a rich cloth, raising their hands aloft and turning their backs upon her, so that when she throws her leg across the saddle no part of her person can be seen."

Five years earlier, in 1432 the traveler Bertrandon de Broquière was in Hagia Sophia for a service wrote the following:

"I went all day without food and drink, almost to vespers, very late, to see the Empress who had rested in a residence nearby which seemed to me as beautiful as a church, to see her come out and how she mounted the horse. She only had with her two woman and two or three elderly men, and three of the kind of people (eunuchs) the Turks have to guard their women. When she came out of the residence someone brought a bench from which she could mount and then they brought out a very beautiful roncey (horse) draped with rich and beautiful bardings (war armor fittings for horses). Going beside the bench, one of the elderly notables took a long mantle which she carried and then went to the other side of the horse and raised up the mantel with his hands as high as he could. She put a foot in the stirrup and then mounted the horse like a man, and then he threw the mantel on her shoulders."

"(referring to her hat) ...on the point of which she had three golden plumes which suited her very well. She seemed as beautiful to me as she had before. She came so close to me that someone said I should follow behind, and it seems there is nothing to say, except that her face was made-up, which was not necessary because she was young and fair. On her ears, hanging from each one, was a large flat earring with many stones, more rubies than anything else. It appeared, when the Empress mounted her horse, that the two women with her were equally beautiful, and they wore mantles and hats."

Above are sketches of the Emperor John VIII Palaeologus riding on a Russian horse, a monk, and a Scabbard, 1438. Look at the very tall hat worn by the Emperor and the unusual hats on the other two figures. This drawing was made when John was in Florence negotiating a union of the Orthodox and Catholic churches in order to save Byzantium from the Muslim Turks. He was extremely ill during this trip and could hardly walk. They were able to get him into the saddle on a horse so he would spend hours hunting everyday. One of the interesting details in these drawings is that the Emperor was wearing Islamic "Mongol" silk, which was very fashionable at the time. The Italians thought their Byzantine visitors were splendidly dressed in the latest fashion. It's an interesting fact that Muslim men are forbidden to wear silk clothes by the Koran (except for thin trimmings of silk embroidery), although the Turks ignored this restriction. Muslims were also forbidden to drink or eat from silver or gold vessels and men could not wear gold rings or jewelry.

Like the reign of Louis XIV in France, Byzantine aristocrats were expected to spend enormous sums on dress. You could not show up at court if you weren't well-groomed and dressed properly. This was true even for minor officials. Servants also wore uniforms. You could tell everyone's position in the government and court by what they wore. The Russians adopted this same system in their own country.

The primary color of Byzantine court costume for everyday wear was white, which must have been very difficult to keep clean. White was worn by Manuel II and his entourage when they visited western Europe in search for help against the Turks in 1400. He visited England and stayed with Henry IV where historians remarked on the splendid immaculate white garments the Byzantines wore. Clothes could be handed down from father to son and mother to daughter for generations being altered to fit the wearer. Clothes were professionally repaired; once then they were worn out the thread was recycled. The resell of used clothes was a big business. Buyers roamed the streets of the city a buying up old and used clothes. Second-hand clothes from Constantinople were resold in fairs like that of St, Demetrius in Thessaloniki. The washing and cleaning of clothes was conducted as a state enterprise - all the way down to family operations.

Constantine wears his hair in long lanky, loose curls, crops his finely combed beard and it's obvious he has big ears. Small black shoes emerge from under his robe. Byzantine men of the aristocracy and the Imperial court were very concerned with personal cleanliness, particularly of the hair and beard which were kept washed, combed and curled. Emperors let their hair grow long in back and placed it in long loose curls. After the 1438 trip to Florence this hairstyle became one of the exotic Imperial traits of Byzantium that appeared in paintings and sculptures. The French kings copied it for themselves after the state visit of the Byzantine Emperor to Paris. Throughout Europe the emperors had a reputation for being finely and immaculately dressed, even in their poverty.

There was an big Imperial Roman-style bath in the Blachernai palace down the hill from Tekfur Saray that Constantine and John would have used. This bath survived into Ottoman times and you can visit its ruins today. Believe it or not, one Byzantine bath still survives in operation in Istanbul today!

On the left is a silk kaftan from the Museum of the Aga Khan in Istanbul.

On the left is a silk kaftan from the Museum of the Aga Khan in Istanbul.

Constantine is wearing a silk kaftan. We know that the splendid court dress described by Constantine VII Porphyrogenetus (912- 959) in his "Book of Ceremonies" was a kaftan and they came to Byzantium by way of the Caucasus. Kaftans were made using different patterns based on the activity of the wearer, for example we have surviving kaftans from the 8th century that are cut for horseback riding. Everyday kaftans were made of linen with decorative silk bands. You could wear a plain bleached linen kaftan under a silk one, which could even be made a sheer silk material. They had buttons or elaborate frogs as fasteners and could be lined with fur for warmth. Byzantine undergarments for men were made of linen. A complete linen under-dress would have been worn under a kaftan.

There was a guild of linen merchants in Constantinople. Linen has the advantage of being a fast growing plant and that was fairly east to process and was inexpensive. Linen is difficult to dye and was usually woven in natural colors. Colored decorative elements in linen clothes were usually added in wool. Linen was delivered to Constantinople merchants from the provinces in pre-woven sheets. Bulgarian linen was especially valued. Fine linen was valued as highly as silk. One of the finest types of linen was almost transparent and linen was often embroidered in gold thread.

The clothes of everyday people were made of wool, linen or inexpensive silk blends or cheaper grades of silk. Soldiers wore clothing made of felt made from wool. Since the days of Imperial Rome cotton had long been imported from India, later it came from the Muslim countries of the Middle East. Cotton clothes were worn both in summer and winter and the fabric was made in different thicknesses for the season.

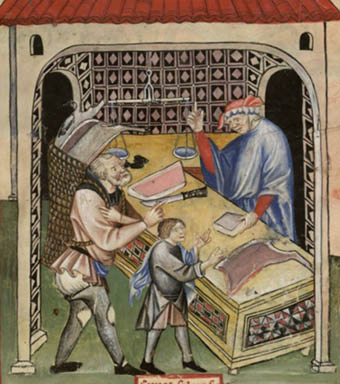

The commercial silk trade was divided into three activities and guilds. First, there were the acquirers of raw silk who purchased it from local producers or imported it from outside the Empire. Second, there were the dyers, weavers and tailors of silk garments. Finally there were specific silk garment merchants.

Sericulture - the production of raw silk - was a seasonal activity from April - June and was a family activity. If you owned mulberry tree groves you could harvest and process the silk in your own operation. Some mulberry groves were divided up and allocated to sharecroppers. Raw cocoons were traded and sent to local centers of silk processing - or were sent to Constantinople, where in the 12th century there were thousands of people involved in the production of silk. There was a very short window for the processing of live cocoons - around three days - so most of this work must have occurred close to the places were they were harvested. Silk that was sent to Constantinople would have primarily consisted of stifled cocoons and silk thread that had been reeled in advance.

Unblemished silk was the most valuable and it mattered whether your silk cocoons were wild or cultivated. Silk cocoons or reeled thread could be damaged in shipping or soiled, which was treated as lower-grade material. Waste material from the processing of silk was spun into low quality yarns and combined with other materials - like wool.

Because of the seasonal nature of sericulture there were annual markets where raw silk was sold. Vast quantities were bought and sold through the markets. Although there were official guilds for the commercial production of raw silk, silk cloth and silken garments there was no regulation on personal production. Since there were so many levels of quality in the making of silk - and that the bulk of production was lower quality, this meant that the majority of silk was woven at home in family operations on family looms. Family operations also produced ready-to-wear garments or specialty tailored clothes.

Around the year 1000, a more advanced hand draw loom was introduced which made the production of some silk cloth (lampas weave) less labor-intensive and cheaper.

Men and women were equally involved in the production of silk in Byzantium and women could even run their own independent businesses. Women managed their own silk shops and worked as sales clerks in them. There were silk workshops in Constantinople that had their own facilities and looms who used hired labor or slaves. This business was highly regulated by the authorities, but only the owners of these operations were required to be guild members. There were no restrictions on Jews in the silk industry.

There was also a unique Imperial silk tailoring workshop that made garments for the state and another workshop that produced gold embroidery. A third Imperial operation connected to the production of silk garments made gold jewelry for the court. The state required huge numbers of silk garments for participants in Imperial ceremonies and events on an annual basis. These garments had to be stored and maintained by trained staff near the palace. When they were worn-out they were sold off to wholesalers. Even the military used silk, where we know it was used in leggings for lower ranked officers.

As already mentioned, silk came in different grades. For the market beyond the palace, a variety of high - and lower - grade silk textiles was available, as well as cheaper fabrics woven of spun floss silk and half-silks combining a silk warp with a wool, linen or cotton weft. Most of the silk produced in Constantinople was made of these lower cost blends, was unregulated, and was a domestic activity woven on those home-looms I mentioned earlier, not in great Imperial workshops. This diversity was meant to cater for the needs of an ever-expanding public with varying buying power, yet keen to imitate courtly fashions for reasons of prestige and to own at least one garment made of precious silk. We know from surviving records that even poor women could own a half-silk or full-silk dress in bright exotic colors or weaves and knew the difference in price and quality. Byzantine-style clothes were sought after all around the Mediterranean and even as far away as Norway and England.

The entire silk-making industry in Constantinople - Imperial and domestic, went up in smoke during the fires of the Fourth Crusade. Some of the silk weavers emigrated to Asia Minor and Latin Greece, where small scale production resumed. Byzantine silks from Greece were highly valued in the 14th century as exports, but eventually Italian-made silks ended their manufacture. Also, as styles evolved western consumers came to prefer eastern silks of Islamic or "Mongol" designs.

In the 12th century high-status men switched from the wearing of tunics to wearing long kaftans with tight sleeves. Another new fashion men picked-up was the wearing of fancy belts or sashes with their kaftan. It was thought the pulled in waistline of the belt showed off the male figure. Constantine's kaftan has been sewn with lines at his waistline. This was done no only to emphasize the waist, but had the practical objective of making it easier to wear it with a belt. A well-dressed man Byzantine could have dozens of belts made of leather or fabric that were adorned with gold or metal ornaments and even gemstones and pearls. Brides gave their husbands jeweled belts, Maria of Antioch gave her husband a belt with a gold, pearl and jeweled buckle that had an inscription to her husband Manuel I Comnenus pledging her love and fidelity.

Men also started carrying money pouches that hung from the belt. You can see Constantine has an embroidered linen or silk handkerchief with a fringe on it, this is another sign of his sophisticated elegance.

As far as jewelry is concerned men Byzantine men wore rings which could either be signet rings or religious ones with prayers and images of holy figures. They also wore wedding rings. A woman would give a man a gold or silver ring to symbolize her softness and purity an a man would give his wife an iron one to indicate his strength and promise to protect her.

Men did not wear earrings - sometimes baby boys had their ears pierced. Women of all classes wore earrings and there were inexpensive fashion knock-offs of the most valuable women's jewelry in base metals set with glass gems.

Everyone wore neck pendants or enkolpion cross reliquaries. After death enkolpion were often displayed on an owner's tomb or buried with them. These were mass-produced all over the Empire in copper alloys (like brass) and many examples have come down to us from the 11th and 12th centuries from burials. Rich and fashionable young men could wear gold necklaces or jeweled collars set with enamels, gems and pearls, but it was not common. It was considered a virtue that a masculine military officer might wear a necklace as a symbol of youthful heroic manliness. Men could also wear adornments on their sleeves and jeweled cuffs, but never wore bracelets.

Everyone wore neck pendants or enkolpion cross reliquaries. After death enkolpion were often displayed on an owner's tomb or buried with them. These were mass-produced all over the Empire in copper alloys (like brass) and many examples have come down to us from the 11th and 12th centuries from burials. Rich and fashionable young men could wear gold necklaces or jeweled collars set with enamels, gems and pearls, but it was not common. It was considered a virtue that a masculine military officer might wear a necklace as a symbol of youthful heroic manliness. Men could also wear adornments on their sleeves and jeweled cuffs, but never wore bracelets.

In the Imperial family it was customary for men to give crowns to their brothers, fathers, cousins and uncles when they were elevated to positions of authority that allowed crowns to be worn. They often carried donor inscriptions pledging loyalty to the receiver. These crowns helped to strengthen the bonds of blood and family.

On the right is a image of guys wearing Byzantine peaked hats called skiadions "shaders". Byzantine hats - as strange as they may look to us today - were thought to be very smart and fashionable at the time. They became fashionable in the 11th century. Prior to that Byzantine men went without hats or wore head scarfs. The Byzantines copied the turban from Mamluks of Egypt. The guys in the back are wearing them.

On the right is a image of guys wearing Byzantine peaked hats called skiadions "shaders". Byzantine hats - as strange as they may look to us today - were thought to be very smart and fashionable at the time. They became fashionable in the 11th century. Prior to that Byzantine men went without hats or wore head scarfs. The Byzantines copied the turban from Mamluks of Egypt. The guys in the back are wearing them.

Constantine's wife Eirene is wearing a jeweled peaked crown from which are suspended ropes of pearls, gold and gemstones and large jeweled earrings. I'll bet the earrings are a pair she actually owned. Earrings were often the most expensive possessions in the Byzantine wardrobe and - unlike crowns - were worn by all classes. Eirene wears a heavy red silk and gold "chysokokkinon" in two colors. The smock-like top part descends to the knees with a fringe. Underneath is a matching dress, "roukon", in the same silk. The dress, which is lined in cream silk, has a high color and jeweled cuffs above the elbows, which are in heavy silk embroidery. Eirene's hair was been pulled back and falls in a long plait behind. Byzantine women wore heavy make-up and often wore wigs. Women used face powder, rouge, eye-liner and eye shadow. Women's fashions were more conservative than mens' were.

Both men and women used perfumes, mostly herbal and natural scents, especially rose water, which could be made at home and freely used, even as a room scent. It was customary to anoint visitors and guests with it.

Byzantine men and women (especially the young) of fashion followed the latest exotic styles from foreign courts at home and in society, but if they were at court they had to follow dress rules. However, during the reign of Andronikos III (1328-1341) there was a loosening of court protocol and he allowed anyone to wear what they wanted around him. This freedom of fashion led immediately to appearance of clothes and hats in Italian, Serbian, Bulgarian and Syrian fashion everywhere. Andronikos also eliminated protocol and established casual relationships with members of his court. Before this it had been easy to tell Byzantines from foreigners in Constantinople, since they dressed differently.

Except for the female crown, this is everyday garb for Constantine and Eirene and it is how they would have dressed when they lived in the palace. The silk would have been locally made. At this time Byzantine silk production was still going strong and was focused on a local consumer market rather than foreign exports. Silk production depended on a steady supply of raw silk and the skill of dyers and weavers who continued to make garments, home goods, drapery, banners and tapestries well into the 15th century. The production of raw silk came from outside the city so it survived 1204. Dyers, weavers and the makers of silk garments fled the city taking their craft into Greece and Asia Minor where there were enough customers to actually see an expansion of the silk business. After the reconquest of Constantinople many silk workers came back to the city. Those that remained in Nicaea after the Turkish conquest helped found a new Ottoman silk industry there.

Below is another picture of Byzantine men wearing crazy hats and fantastic turbans. Unlike the custom in western churches, the Byzantines wore hats in church. The Ottomans inherited the wearing of turbans from the Byzantines who invented them. Hats on men were marks of rank or occupation The stripes indicate the office held by the wearer. I assume that these are portraits of Serbian court officials..

It is interesting that the Italians in 1438-1439 who witnessed the visit the Byzantines to Florence thought that the costumes they wore were what the ancient Greeks wore. The Italian humanist Vespasiano da Bisticci wrote:

It is interesting that the Italians in 1438-1439 who witnessed the visit the Byzantines to Florence thought that the costumes they wore were what the ancient Greeks wore. The Italian humanist Vespasiano da Bisticci wrote:

"I will not pass without a special word of praise of the Greeks. For at least fifteen hundred years and more they have not altered the style of their dress; their clothes are of the same fashion now as they were in the time indicated"

The Byzantines knew their court and popular dress for men was not ancient Greek, but they thought it pre-dated Alexander the Great in the court of Persia.

As already stated Constantinople was a huge market for both new and used clothing. The domestic clothing industry exploded in the 12th century. Tailoring clothes in fabrics like silk and linen, often combined in the same dress or tunic, required enormous skill and the space to cut the patterns. Every fabric was different and the cutting of patterns in one direction or another mattered. In the case of silk you needed a lot of it to make a kaftan or a dress like Constantine and Eirene are wearing. Most commercial silk was woven by home workers in standard sizes. Weavers could be men or women. Some were organized into cooperatives and were clustered in certain neighborhoods. In the 12th century there were thousands of home weavers working in the city. Weaving was considered an esteemed, professional craft and weavers had to keep up on the latest patterns and trends in popular colors. Middlemen bought the silk from them and sold it in big bundles for export or the domestic production of clothes. The quality of the silk, the weave and its thickness varied, so Byzantine tailors had to be experts in working with it. In Byzantium tailoring clothes was a professional business and not a DYI affair. The making of clothes required lots of room, which private homes didn't have and as a highly urban society Byzantine weavers did not have direct access to the materials used in making and dyeing of yarns.

There were ceremonial occasions when the merchants, guilds and common people were required to dress up in fancy outfits. There could be thousands of people involved. If the guilds could not supply these the Imperial court had thousands of silk outfits in storage that they checked out to the public to wear. These were not always kept in the best condition and could be 100 years old. In the 10th century one foreign ambassador reported processions of thousands of people - all in tattered, ill-fitting or worn silk costumes. By the 12th century travelers consistently praised the citizens of Constantinople for their fine dress.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints