Where is the Deesis Located?

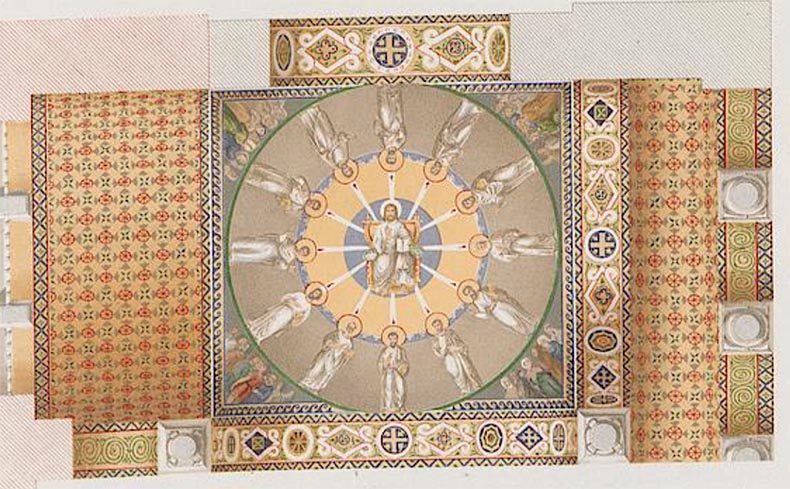

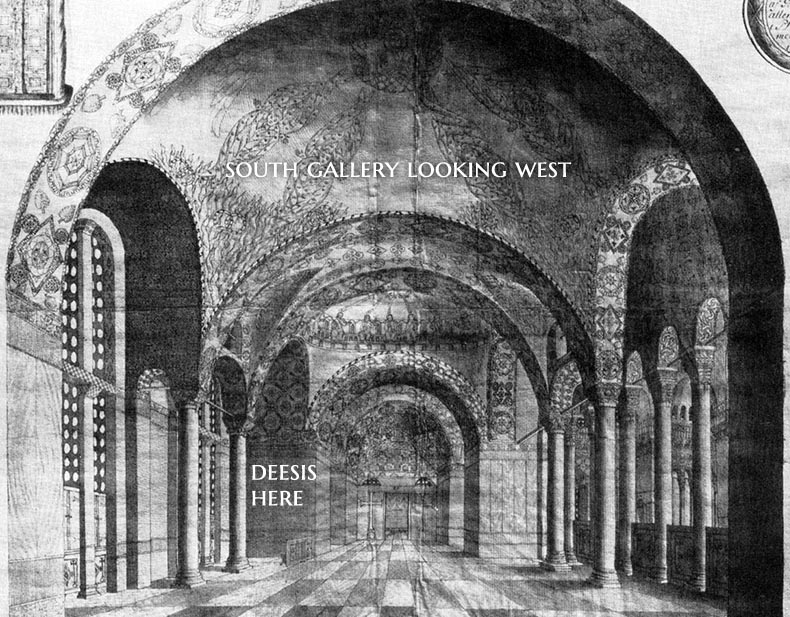

Above are two images. The top one shows a drawing of the South Gallery of Hagia Sophia from the 18th century with all of the ceiling mosaics (see all the cherubims!) intact. In the center of the vault is a round image of Christ Pantokrator. I have indicated the location of the Deesis on the left. To the right of the Deesis you can see a low marble parapet to separate the area in front of it from the rest of the gallery. From the drawing we can tell that the parapet dates from the time of Justinian and was carved with crosses and foliage. The parapet was Byzantine, not Ottoman. There were more than 140 cross-decorated panels like this that were carved for Hagia Sophia when it was built. It is remarkable that this parapet with its crosses was left undisturbed for hundreds of years after the Muslim conquest. Look at the back of the marble door in the distance and you can see the cross arms are still there; today they are damaged like most of the other crosses in Hagia Sophia. The parapet has vanished but ghostly markings of it can still be seen in the marble floor. You can also see the marks in the floor left by a big silver-gilt candle stand in front of the Deesis.

The image below it is one I found from the 1930's that was scanned from a color transparency at Dumbarton Oaks. The colors have shifted. It shows how the first band of marble was pieced together from mismatched bits and was overlaid over part of the bottom of the mosaic. It is made of Proconnesian panels with one square of Pavonzetto on the left. This was probably added during the Fosatti restoration. From watercolors made by the Fosattis we know that the bottom part of the mosaic was gone down to the level of the bricks by the time they uncovered it.

This is best picture I have found that shows the proportions of the figures. It was taken by the Byzantine Institute to document how they found the mosaic and its setting. We can see there is plenty of room for the full figures of all three and the cushion below the feet of Christ if you remove one row of marble. We know for sure that the mosaic extended down to the bottom row because mosaic setting bed was found behind the upper row, but not below it. We can also see the bottom row is original because the wavy grain matches up.

The bottom band of carved marble is original, you can see had been made to fit to the curve of the floor, which was created by the distortion of the building while the mortar was drying. You can see the curve at the far right corner where the parapet was attached.

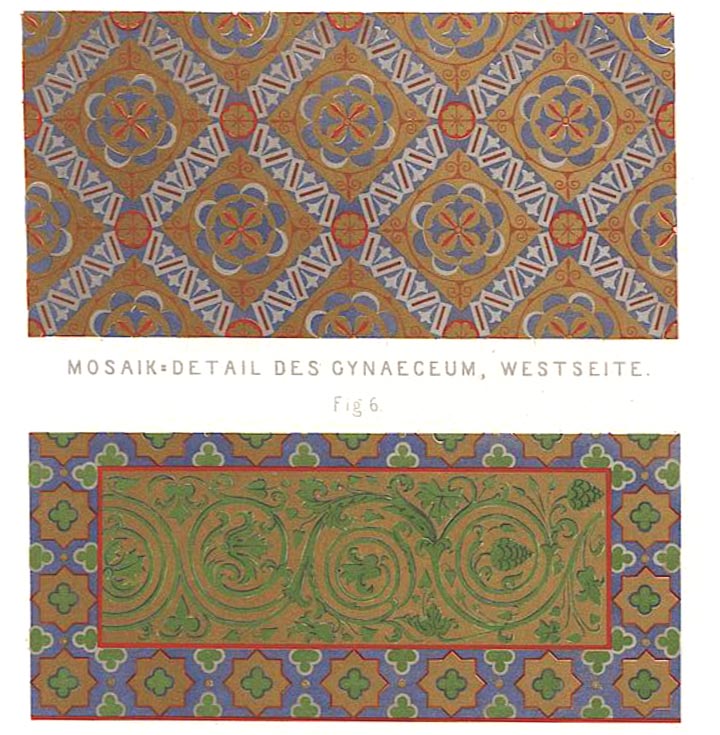

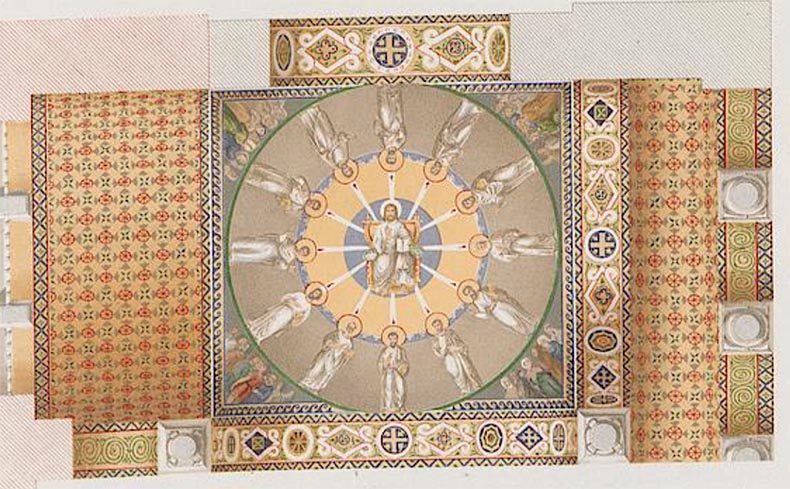

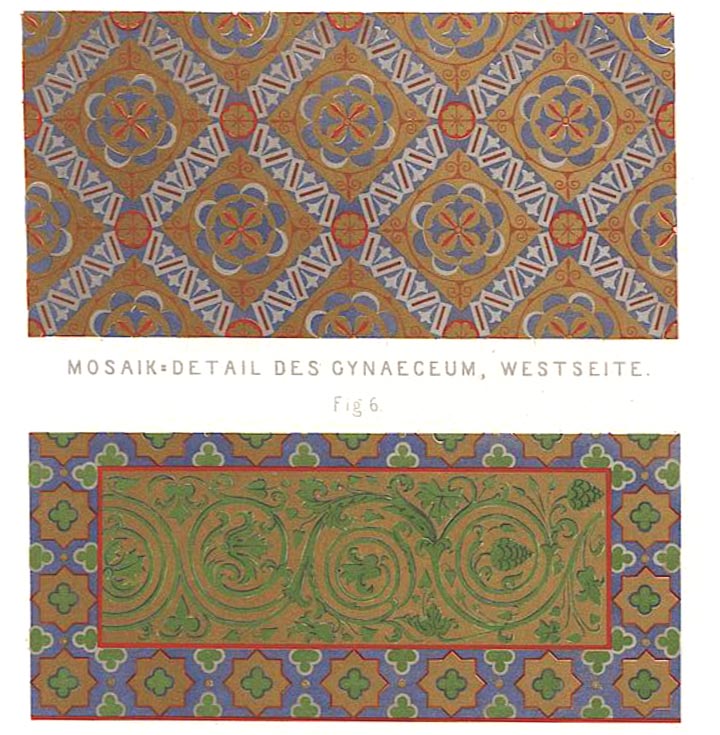

Above is an image painted by Saltzenberg in 1850 which shows what was in the vaults above the Deesis. Saltzenberg has restored and filled in some of the missing or fragmentary parts. It seems that only part of the central medallion had survived until then. Besides the apostles and Mary the Theotokos surrounding the central medallion, one can see groups of people in the corners. These represent the many nations of the world the preachers of the Gospel would reach. The patterns in the vaults are more regular than they would have been, the originals were laid freehand and irregular. Saltzenberg used mechanic tools to reproduce them. Something mysterious happened to these mosaics - by 1930 they had vanished! Below is another Saltzenberg image which shows the pattern that was in the arch vault directly above the Deesis. All of this could be seen from elsewhere in Hagia Sophia and was especially beautiful from the floor of the nave, which Saltzenberg saw for himself. He specifically mentions the gold flashing like fire in the vault mosaics which was appropriate for a mosaic of Pentecost. The two pictures below are of decorative patterns in the vaults of the upper galleries that he recorded in on-the-spot watercolors and drawings he made. These must date from Justinian's original decoration.

Size and Scale of the Deesis

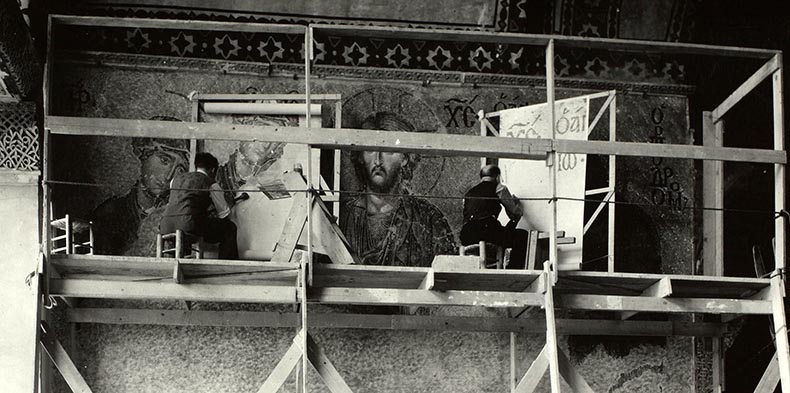

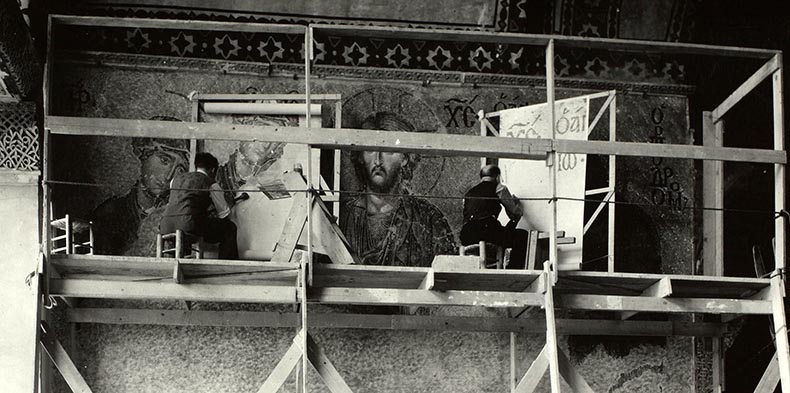

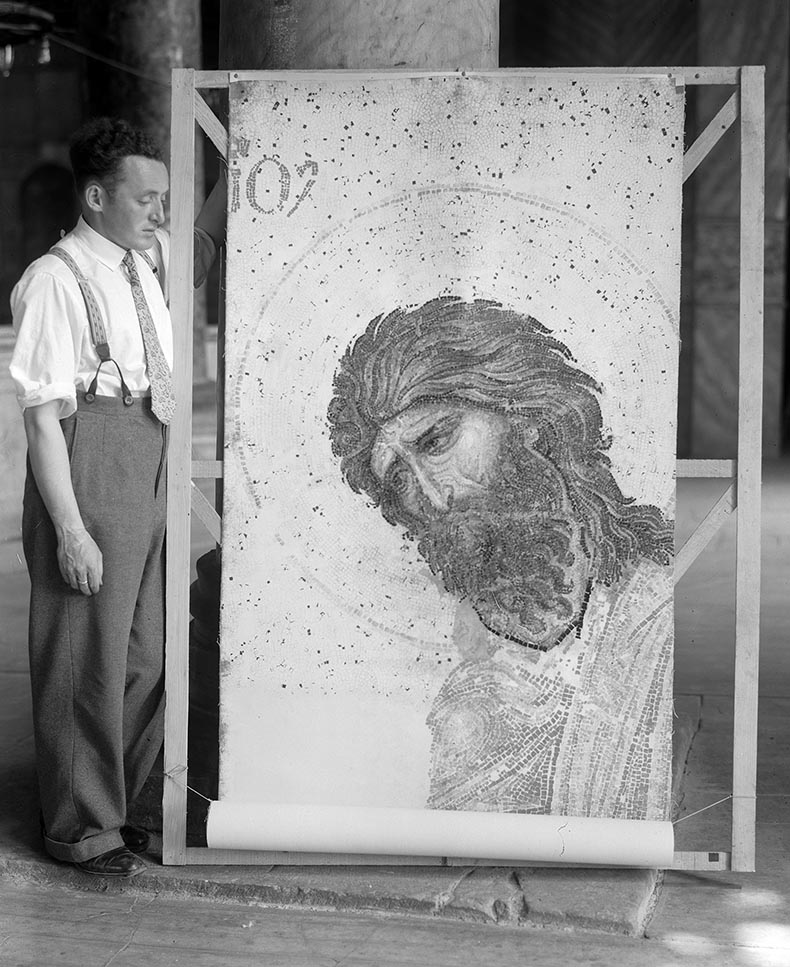

Below you will see a picture from 1938 or 1939 of Alwyn Green, who created a hand-painted replica of the Deesis. Below that image is one of Nicholas Kluge who worked with Alwyn on the tracing of the Deesis. Tracings were made on site and then sent to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where it was photographed, backed on linen and returned to Istanbul to be copied in colors by Alwyn. One of the restorers, George Holt, of Bennington College, created the process and published an article describing it in 1939.

Here is the Virgin's face. You can really see the huge scale of the mosaic. They made these my pressing some kind of paper to the surface of the mosaic to get a cast or every cube. Then they hand-painted each cube while on a scaffold you can see them working below. They painted right there to match the color perfectly. One of the things about the mosaic of the Deesis is the light rakes across the surface and dives into transparent glass cubes. This both lightens them in color and charges them up with an unearthly energy. The artists were able to get the colors right. When you take a picture with artificial light from the front this effect is totally lost. Below in the picture of Nicholas Kluge, with his back facing the camera, you can see in the distance a tracing of the figure of Constantine Monomachos from the South Gallery hanging from a window ledge.

The Copy is in the Met - Go See it!

Above you can see the actual painting they were creating. It was first exhibited in 1944. It's 13 x 20 feet and now on view at the Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 305. Go see it! Tell the curators you like it and you know where it came from - they will be surprised! It was sold to the Met for $7,500.00 and put on exhibition along with other Hagia Sophia tracings in March 1944.

Probes beneath the surface of the existing mosaic and cornice showed that there was an earlier mosaic in the spot now occupied by the Deesis. It was probably a decorative panel. Remembering Iconoclasm, Byzantines would never have destroyed a mosaic panel of Christ or the saints if one had been here before. The only possibility would have been if a mosaic of a deposed Patriarch or Emperor was here, one whose memory had been damned and all images of him were ordered effaced. A number of gold tesserae made of darker glass were found beneath the cornice and these appear to be of sixth century manufacture.

Are the Experts Wrong in the Date of the Deesis?

Most experts believe that the mosaic was erected after the restoration of the Empire in 1261 as a thank offering from Michael VIII as a part of his restoration of Hagia Sophia. I believe the mosaic was made in the reign of Manuel I Comnenus for a number of reasons. The first is the artistic quality of the mosaic. The second is the fineness of the mosaic. The Deesis is made of excessively fine mosaic in many colors and shades. Some of the cubes are the size of a pin-head. The mosaic is laid in a luxurious way with elaborate patterns and delicate contrasts of tones unlike any other monumental Byzantine mosaic that has survived. It resembles a miniature mosaic produced on a grand scale. It seems to me, after 1204 when the mosaic workshops and their supplies had been destroyed, it would have been impossible to organize a project like this. We know that some fresco painters remained in Constantinople, in 1220 Sava of Serbia hired some to paint a church in Zica. There is no mention of mosaic artists working in Constantinople during Latin rule. Also, Michael had a bad relationship with the clergy of Hagia Sophia and this conflict resulted in an upheaval in the operation of Hagia Sophia; Michael VIII was banned from Hagia Sophia because of his attempts to unite the Eastern and Western churches. Also, the location of the Deesis was not accessible by the general public, only to the patriarch and the clergy, who had become the enemies of Michael VIII. It was not a place where you would want to put a work of art that you wanted the people to see up close.

Most of the planning for the mosaic would have taken place on the very spot where it was created. Mosaics were were expensive, long lasting and high-prestige commissions that lots of people would see and admire. I believe this project in Hagia Sophia involved both the creation of the Deesis and another mosaic of Manuel I and his family on the facing wall. That mosaic could have involved an image of Manuel with his wife Maria and their son, or a panel of Manuel with his father, John II and Manuel's son, Alexis II. There would have been a dedication inscription in the form of a poem-epigram on the mosaic praising the virtues of Manuel.

Manuel was tall and swarthy in appearance. He wore his straight hair to his shoulders and had a trimmed beard. He grew up to speak many languages, including French and probably Arabic. He had the sun burnt face of a soldier and a muscular body, he was a bit hunched over because of his height.

Manuel believed that Christ spoke to him directly and he even created an image that he used showing Christ speaking into his ear to illustrate their close relationship. Manuel saw himself as the champion of Orthodox Christianity, chosen by God Himself as Christianity's standard bearer. This sounds like a case of a narcissistic personality disorder and Manuel probably suffered from one. He always saw himself as being outside of the norms of human - and Christian - morality. Once he took the throne he became the object of the Imperial court's constant adulation. It probably was unprepared for it because he had not been expected to become emperor and his father had not prepared him to resist flattery. Like a narcissist he believed the praise he received was both true and deserved almost until the end of his life. His reign was marked by what appeared to be great successes but they were cancelled out by terrible military defeats like the battles of Konya and Myriokephalon, for which he should have taken personal responsibility.

His narcissism extended into his personal sexual life. Since he had not been expected to reign he had been permitted to live a dissipated life as a young man and sow his wild oats wherever he wanted, including among his own female relatives. His face was marked with the signs of a venereal disease. Historians of the time believed these marks were caused by his general licentiousness and promiscuous sexual relations with women, including his own niece, Theodora, with whom he had an illegitimate son! The boy was raised openly in the imperial court where his father recognized his parentage. Manuel was not ashamed to be seen with Theodora and their affair was conducted in public. The church said nothing. He must have had hundreds of sexual partners. Manuel detested his German wife, Bertha-Irene who was not attractive and was probably sexually frigid. He built her a big towering palace in the Blachernae, covered her in silks and jewels - and then ignored her. She bore him a daughter, named Maria. This all seems strange when one considers his mother was made a saint in the orthodox church and his father was supposed to have set rigid standards for his family - especially his sons. Perhaps this did not extend to his sexual relations which his father could have seen as him just being a man and having masculine passions. John and Irene seem to have given most of their attention to the two eldest boys. Alexios was a paragon of virtue and devoted to his wife.

Although Manuel had loose morals his father recognized he was a fierce warrior and instinctive ruler of men. John had taken his entire family - boys and girls - on campaign with him. His wife went, too. They traveled all over the Empire, visited many cities and met many people of all classes along the way. Most of the time was spent living outdoors in military camps. This gave John the chance to know his sons very well. He saw Manuel throw himself into difficult battles at great personal risk. He killed men in hand-to-hand combat. He was considered a hero by the troops. John passed over his eldest surviving brother and left the throne to Manuel because he was convinced he had a strong and determined personality.

John must have discussed his plans for Manuel with him after his two eldest brothers had died. There wasn't much time between their deaths and John's own. Manuel must have seen he had been destined to rule and that God had been involved in his assumption of the throne. The deaths of his two brothers then followed by his dad's must have seen like interventions of Christ, despite their tragedy. Believing God had chosen you personally to reign as the most powerful ruler in the Christian world was a heady way to assume the throne. One can only imagine what it was like to be crowned in Hagia Sophia - the exhilaration, joy and exhaustion he must have felt. When he received the sacred anointing of holy oil he was no longer just a man, but something of a demi-god that was closer to Christ than anyone else. I do not believe that Manuel would have felt any fear at the responsibility he was assuming. He would have immediately wanted to set his own mark on the most important symbols of imperial rule like the public forums, palaces and especially Hagia Sophia. He would have sought Christ's inspiration and direction in the design of the Deesis mosaic. He should have been afraid of the praise he received that he was like Christ in wisdom and even in his appearance as a temptation from Satan, but he didn't. The Deesis was his own personal and very public ' thank you' to God, and it became one of two Manuel's "official" icons of Christ. It was a brave move to place it in front of the Patriarch's own throne and an assertion of his supremacy over the church (like Henry VIII, another narcissistic ruler). Manuel saw the Deesis as one of his first public monuments in a new Golden Age he would lead.

There was a lot going on at the beginning of Manuel's reign that involved new buildings and art. His new official portrait was created, copied in thousands of replicas and was sent throughout the world. They were set up all over Constantinople for the people to see, where they were given semi-sacred veneration as images of Emperors also had since Roman times. There were big projects in the city Manuel commissioned. There was a lot of money left over from his father's frugal reign. The workshop that made the Deesis moved from one big project (both secular and religious) to another for Manuel. Perhaps they had worked before on the mosaic of Manuel's parents. They were obviously talented and experienced, the best there was in the Christian world. Manuel used gifts of mosaics to foreign courts to assert his superiority over them politically, spiritually and culturally. Much more than fresco mosaics were a luxury art that overwhelmed the places it was used. Manuel used it to showcase the heroic glories of his reign and to promote himself as the champion of Christianity everywhere. The mosaics Manuel gave to the church of the Nativity in Bethlehem are good example. Manuel even signed them!

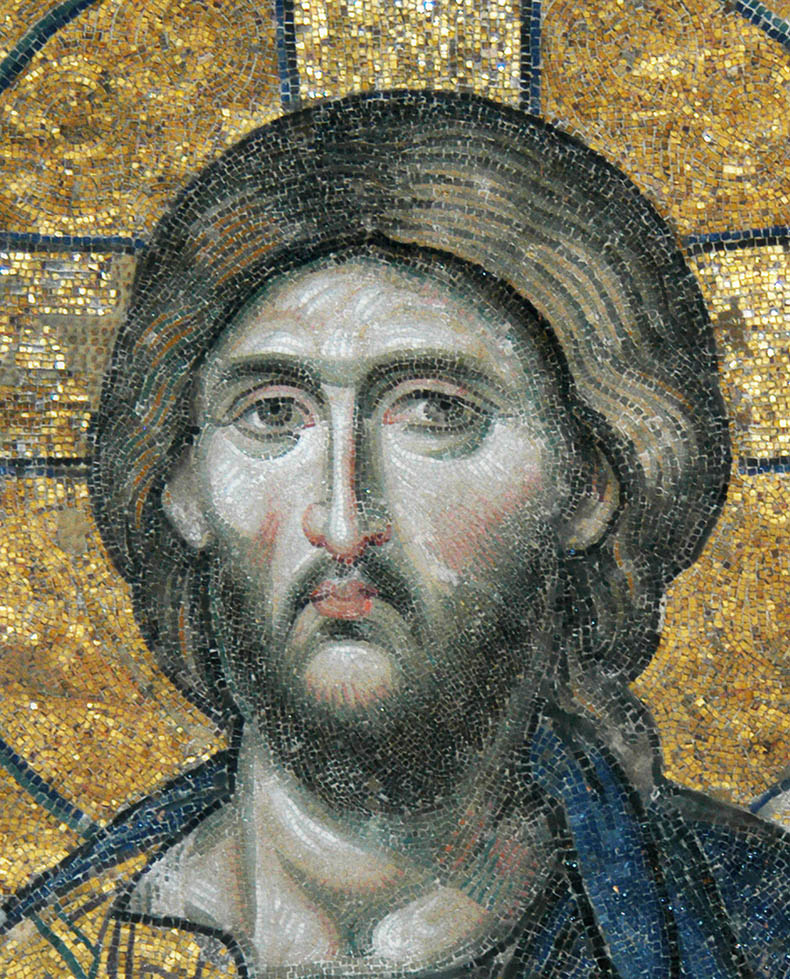

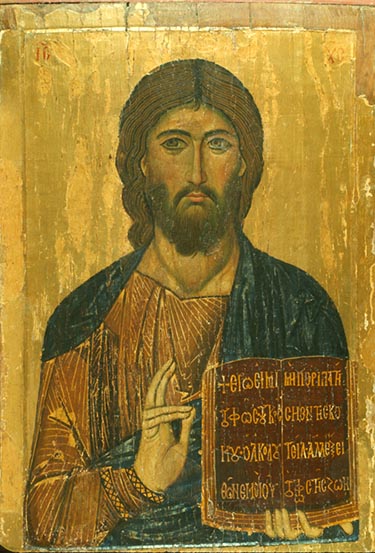

Below is a picture of a lead seal used by Manuel's first wife, the German Princess Bertha, who went by the name of Irene when she moved to Byzantium. You can see an image of Christ sitting on a straight-backed throne holding the Gospels in His lap. The position of the figure is the same as in the Deesis. While these images of Christ Pantokrator may seem conventional and all basically the same this image is unique. I even notice the beautiful folds in Christ's chiton - something Whittemore noticed - can be seen in the lead seal. The position of the fingers caused by the holding of the gospels in the lap is seen both in the seals and also in the mosaic. Manuel I used two images of Christ on his coins and seals. One was of the youthful Christ Emanuel in a circle. Manuel used this icon because his name, Manuel, meant Emanuel. Besides his wife Bertha his son Alexios II also used this same seated Christ on his seals. It seems the image of Christ in the Deesis was a dynastic symbol Manuel used as his own Imperial imagery.

First Possibility - Manuel's Coronation in Hagia Sophia

There are three occasions when Manuel might have ordered the Deesis mosaic for Hagia Sophia. The first was in the first year after his coronation. After he was crowned at the ambo by the patriarch, Manuel placed 100 lbs of gold on the altar as an offering to the church. A year later he made a special offering of 100 lbs of silver to the clergy of Hagia Sophia. Perhaps this distribution was associated with the mosaic. This is the date - 1143 - that Thomas Whittemore prefers. Manuel married Bertha-Irene in 1146 in Hagia Sophia. She used this image on her seals so it must have existed at the time of their marriage. Whittemore also sees the Deesis as directly connected to the Byzantine mosaics of Sicily. He also sees a technical and artistic relationship with the portrait of Manuel's older brother, Alexios, in the nearby mosaic his parents put when he was crowned in 1122 when he was 16. Alexios died before his father in 1142. The next brother in line, Andronikos, died escorting his brother's body back to Constantinople. Although he had been the last of the four sons John passed over the third, Issac, in favor of Manuel. It's possible there were no mosaics of Manual in the South Gallery when he took the throne and this is something he would have wanted to rectify as soon as possible.

Second Possibility - an Important Church Council

The second occasion was a church council held on the question of whether Christ had offered himself as a sacrifice for the sins of the world to the Father and to the Holy Spirit only, or also to the Logos, meaning himself. This debate started out small but grew into controversy because Manuel took a personal interest in it and forced the church to debate it. Rather than providing answers the decisions of the council created more confusion and a new council was held in 1166 to resolve them. Manuel considered himself an expert (even a genius) on Theology. Manuel's name means "Christ with us" and everyone was aware that Manuel was convinced he had a special relationship with Christ. He became personally involved in the discussions and forcefully his own views known. Manuel even went so far as to meet with individual members of the clergy of Hagia Sophia and argue his position personally. This alarmed them - who knows what crazy ideas or reasons the Emperor might use. You might agree with something under pressure that could get you defrocked. The clergy told Manuel that he was no longer allowed to meet with them privately and must address them as a group. This would have been around 1157. Manuel could have addressed them in the South Gallery in front of the Deesis, another sophisticated example in art of his knowledge of Theology his unique relationship with Christ.

The mosaic could have gone up during the time of Patriarch Luke Chrysoberges who sat on the patriarchal throne from 1156 until 1159. One of Luke's top accomplishments was he abolished the practice of clergy taking paid secular jobs.

The Great Marble Inscription

Manuel ordered a huge inscription recording the decisions of the council carved on marble panels for Hagia Sophia. They have miraculously survived, having been reused as ceiling panels in one of the nearby Ottoman mausoleums. Originally, The were placed on porphyry columns on the left side of the nave. The inscription is a bravura piece of Comnenian philology that would have been appreciated by the clergy of Hagia Sophia. The council met in Hagia Sophia and in many other places in the city, including the Boukoleon Palace and Manuel's new throne room in the Great Palace. Manuel seems to have preferred to hold the council in his own palaces, where he had more control over the deliberations and could dazzle the participants with his knowledge and hospitality.

Patriarchal Balcony Over the Nave

The center of the South Gallery acted like a patriarchal balcony over the nave of Hagia Sophia, and the patriarch blessed the clergy and worshipers in the church from here. The patriarch processed with the clergy from both the east and the west. They used the imperial wooden staircase or the SE ramp - both built by Justinian - when the procession originated in the sanctuary and was headed for the south gallery. This SE ramp was destroyed when the first minaret was build by Mehmet II. When the procession began in the patriarchal palace on the SW side it would move from west to east. All processions in the South Gallery would have taken them past the Deesis and required a stop to venerate it. The procession from the east would have been the most important for the veneration of the Deesis, since it faced in that direction. The face and hand of Christ were designed to follow you as walk that way. It is possible that there was a Patriarchal throne throne in the central bay of South Gallery. If there was one it could have been placed on the eastern wall, opposite the Deesis, where the tombstone of the Venetian Doge Enrico Dandalo has was set in the 19th century.

Third Possibility - Manuel's Second Marriage in 1161

A third possible occasion for the creation of the Deesis was when Manuel remarried at Christmas 1161 (his first wife, a dour German Princess named Bertha, had just died). After considering a Crusader bride from Tripoli Manuel chose a gorgeous young blond French princess of Latin Antioch as his bride. I have often wondered if there is a connection between the youthful, soft beauty of the Virgin in the Deesis and the arrival of Marie in Constantinople followed by her marriage in Hagia Sophia. Perhaps the mosaic was made during the summer of 1161 while Maria was on her way from Antioch. From all of the thousands of images of Manuel that were created during his lifetime, only one survives showing Manuel and Maria at the time of their marriage. This image agrees with written descriptions from the time.

Manuel never saw his obsession with sex as an impediment in his relationship with God. Manuel believed - as an absolute monarch chosen by God - that he was not restrained by any moral code and did not feel any guilt for his conduct. One might go so far as to see a resemblance between Mary the Theotokos, Christ in the Deesis and the Imperial couple. Her name was Maria and his was Manuel (Emmanuel); their portraits are below. Manuel's jeweled costume, called a loros, was heavy embroidered in gold thread and set with enamels, jewels and pearls. They were made in the Imperial gold embroidery workshops near the Great Palace. It was very heavy and only worn twice a year. It was sometimes displayed in the gallery of Hagia Sophia for the public to view. The crown was made of gold and had a closed, domed top. It was set with a famous huge ruby in front. This stone could switched with others in different colors. Crowns and other jeweled objects, including enamels, were made in another Imperial workshop.

Another indicator for 1161+ is the amount of time Manuel spent in Constantinople after 1160.

How Were They Made - Unanswered Questions

As the commissioner of the Deesis, he would have been expected to provide all of the materials for it. He would have picked the rare and expensive for the mosaic. There was an existing mosaic here, we don't know what it depicted. It might have been a huge plain gold field or had a non-figurative design from the era of Justinian. The emperor would have involved theologians, poets as well as the artists to discuss the purpose of the mosaic and what it was to convey. This spot was one of the most important in Hagia Sophia and the mosaic was intended to make an important artistic and religious statement. It was also intended to bring glory to the Emperor.

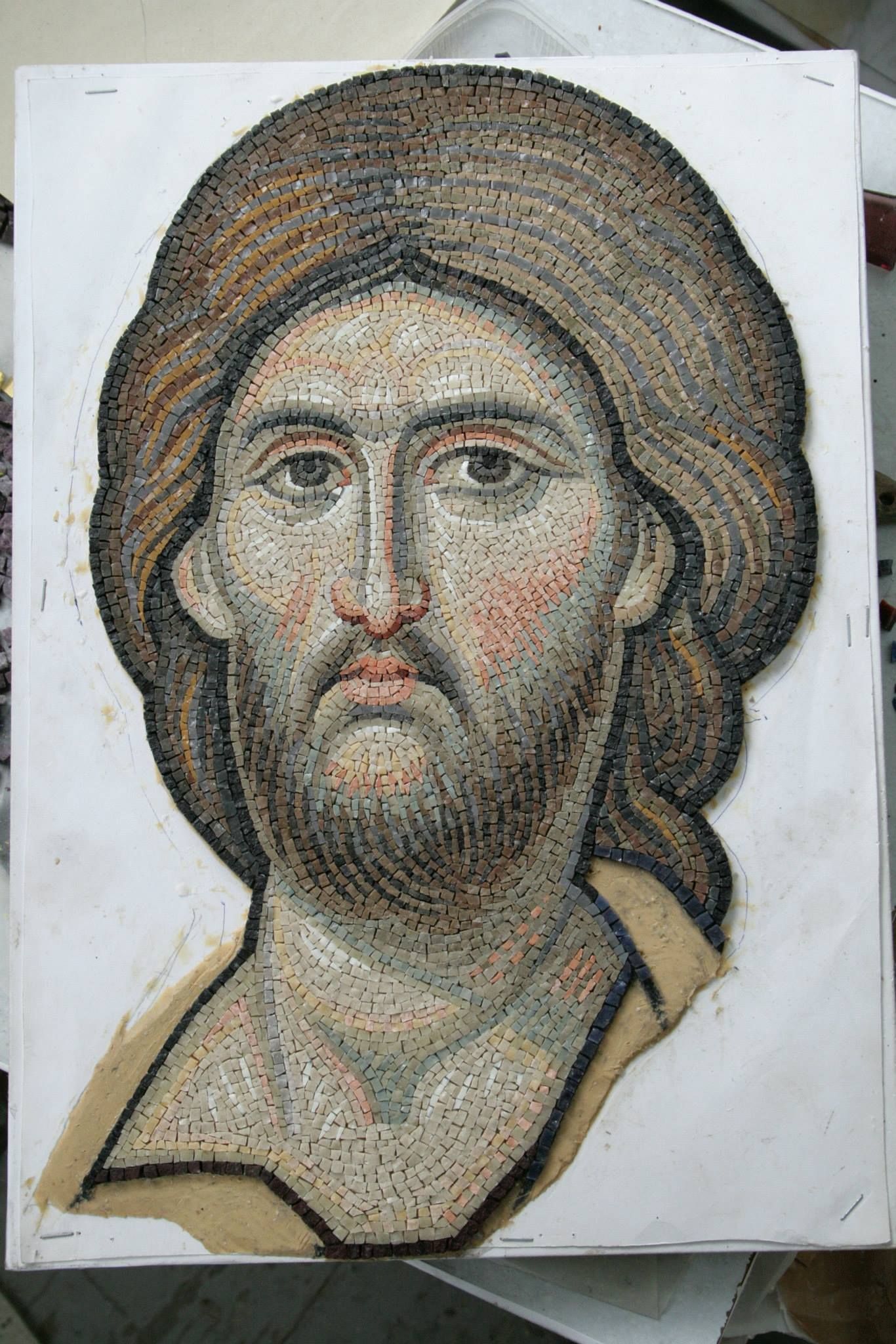

We don't know how the mosaics were put up. There are a huge number of tesserae of many colors in the faces that are laid in complex patterns. Some of the cubes are the size of a pinhead. The cubes used to create Christ's beard are especially fine and many taper to pointed ends. Even though these artists may have made hundreds of similar mosaics and dozens of Christ before the challenges of creating the mosaic on the spot seem impossible to overcome.

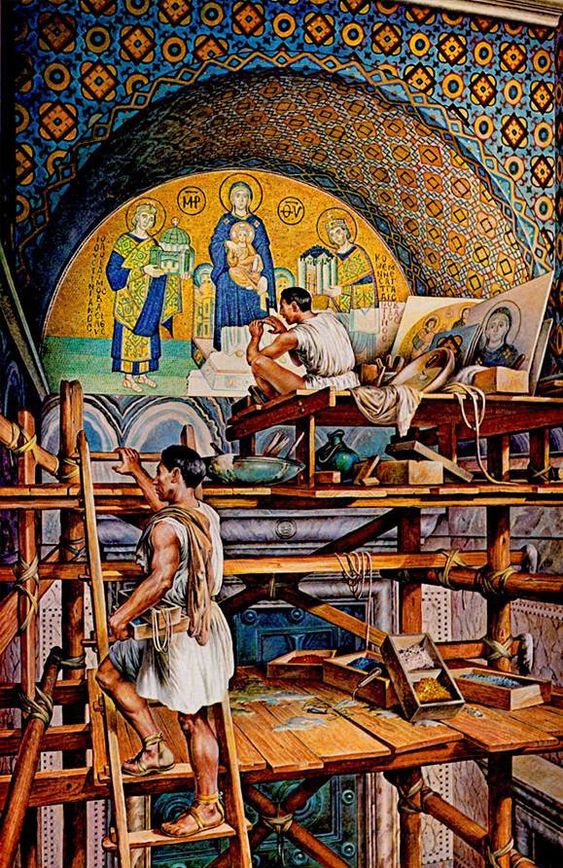

Even though the light in the South Gallery is bright for a large part of the day six people working on the scaffold at one time would cast shadows. Even with assistants each artist would need his own tools and cubes at hand. Most of the colors in the faces are in multiple tones so there were a lot of them that must have been arranged in portable boxes arranged by colors. The boxes must have been organized in advance for the days work and replenished as needed. Cubes would be cut onsite. I can see more than one artist working on the face at one time, but not more than two.

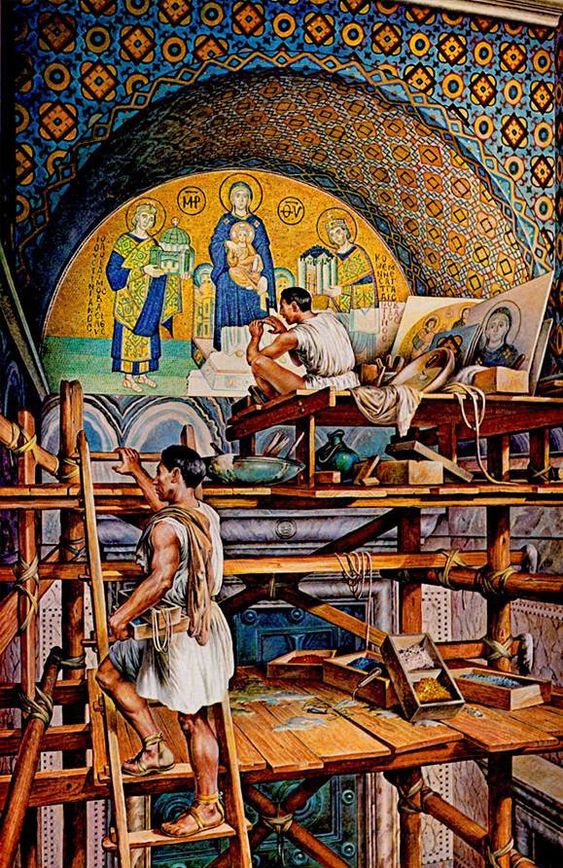

There must have been a great deal of work done in advance to design and lay out the cubes. There must have been preparatory drawings as well. Were these done only on the plaster at the time the mosaic was made by hand in fresco paint? It is impossible for me to believe that the mosaics in the faces were laid freehand, even in the best lighting conditions and regardless of the skill and experience of the crafts people. I think the faces were planned and assembled on some backing and then brought up to the scaffold and pressed into the plaster. After this was done the edge were adjusted. We know that in some cases - like the mosaic portraits of Justinian and Theodora in Ravenna - were made this way. In the Deesis one can see the seams in the plaster in the faces and the cubes that have fallen from them. Later repairs were made to the face of Christ to replace some cubes using beeswax. Today this is how mosaics are made for Orthodox churches and we have the practical example of how they work. In Moscow and Minsk there are workshops today creating exact replicas of 12th century Byzantine mosaics using the same materials. They work out complex mosaics on tables and then transfer them to the final surface. Unfortunately we have no written accounts telling us how the Deesis was made; all we can go by are the seams in the plaster bed and common sense.

The mosaic was repaired at least once during Byzantine times. In view of the frequent earthquakes there must have been inspections of the mosaics of Hagia Sophia, particularly the vaults of the galleries, for loose or missing tesserae. In the face of Christ some cubes have been replaced or reset with wax. Was was used in the production of miniature mosaics so the restorer could have been a maker of them. An layer of wax was found beneath the tesserae in the face of Christ. Whittemore reported this with comment on it its meaning.

We cannot forget the making of mosaics involves a lot of hard physical labor. Beyond the preparation of the mosaic beds there the of hauling and lifting of heavy glass and stone mosaic cubes. One would be up and down ladders to the scaffold many times a day. The higher the mosaic the greater distance one had to travel to get to the worksite. The technique of laying the tesserae is long and tedious work, involving the cutting of individual cubes and pressing them into the plaster. This is repeated thousands of times a day. All the work was done in natural light.

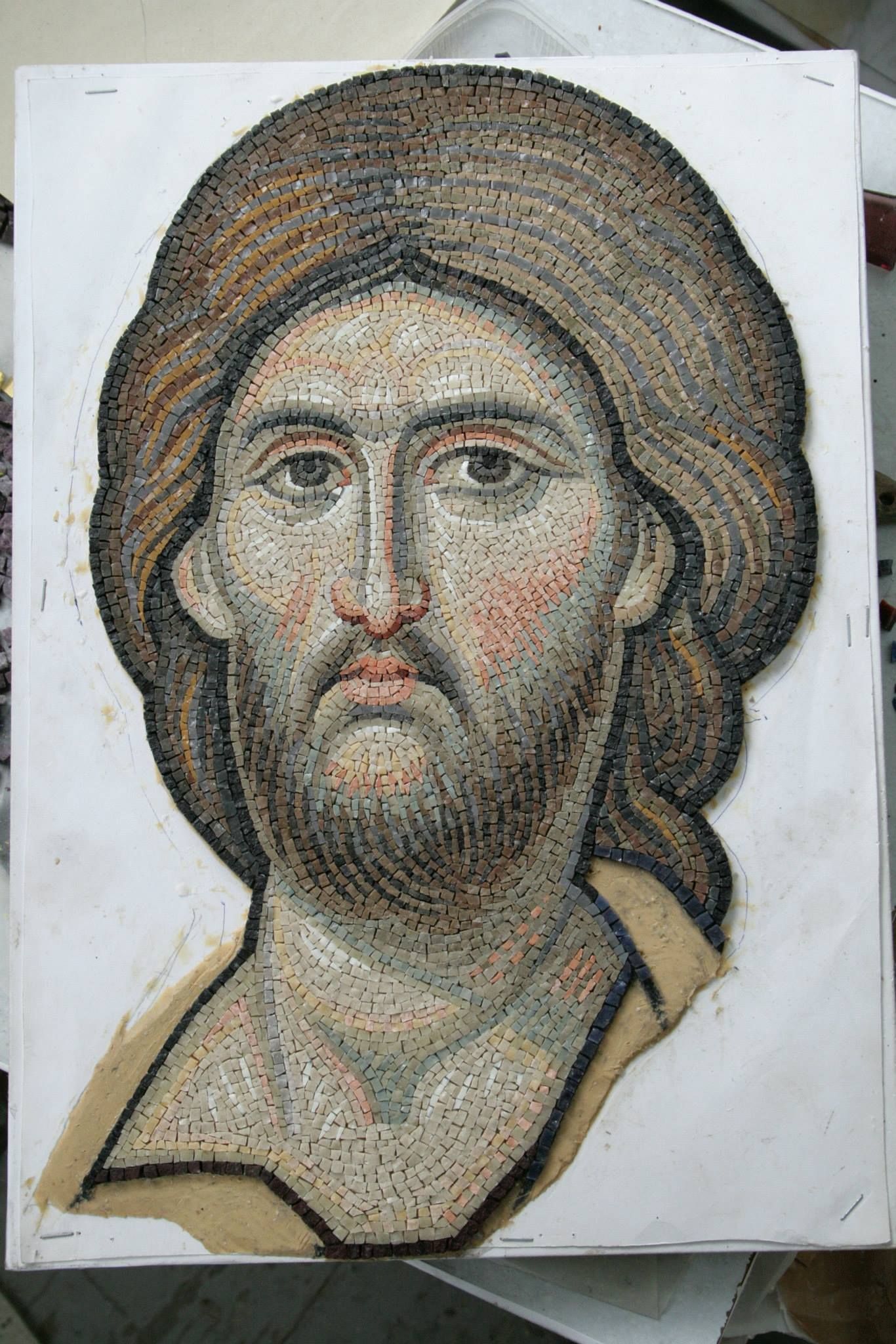

Below you can see a modern copy of the icon of Christ from Hagia Sophia and how it has been laid out on a board. It is probably 1/8th in size. I don't know who created this or where the image originated, I found it on Pinterest:

Importance of Vividness

These figures would have been startling to the Byzantine viewer for a number of reasons. Even though the Deesis was just one part of a vast program of mosaics, they stand out because of their scale and beauty. The most important factor Manuel wanted to achieve in the Deesis was vividness, the figures - and even the background - were to be as alive as possible. Seeing this mosaic - through this ultra-realism - the spectator was compelled to interact with it as a "living icon" that was an image of God full of spiritual energy. This icon was to be as beautiful as human hands could create, designed to appeal directly to multiple senses as a true 'memory' of Christ Himself, one that was immortally alive and perfect. The figures of Mary and John appear to be speaking to Christ, while He converses with us. Thus we experience Christ, his Mother and John as if we were present with them in a divine mystery play set in a cloud of vivid gold mosaic that is eternally repeated. In Byzantine times the sensual experience was enhanced by flickering candles, music, unearthly chanting, fragrant incense and silken draperies.

Face and Robes of Mary, the Theotokos

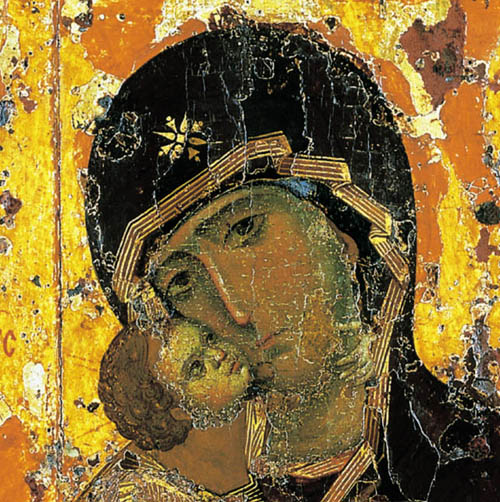

The Theotokos has a breathtaking softness in her face that creates the illusion of a real, living woman. There are details in the face that are unusual - even unique to this icon. For example the artist has outlined the left eyelid in dark ruby and the right one in dark gray. This makes the face softer in its modeling and the right side of the face fades into shadow. I have never seen this before. Also, in the shadow of the face lines of tiny pink cubes are laid right next to contrasting lines of blue-gray which make it appear like real skin in natural light. This mimics the way some icons of the Theotokos from this period are painted in very fine tones. The eyelashes are very subtle and soft. The Virgin's lips are so softly colored and lightly modeled that they almost fade into her face. There is one curious emerald green glass cube laid to the lower right side of the face, below the lips, for which I can find no explanation. Unlike Christ and John the Baptist there are no white highlights in her face - more intentional softness. Her drapery has its own softness and naturalism; it's a shame that more of this figure hasn't been preserved. The maphorion of the Virgin is composed of at least 4 tones of translucent glass cubes in pale gray violet. Whittemore described the color as being like a washed-out cloud. The lines of the folds are in a dark blue opaque glass. The violet cubes might have been reused because their corners seem beat up to me. The color is an unusual and deliberate choice. The giant Kahn Madonna in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC is directly related to the Deesis and could have come from Hagia Sophia after the looting of the church in 1204. A Byzantine viewer would have noticed the soft, heavy, realistic folds of the Virgin's maphorion. It's a shame so much of the figure has been lost. The relationship of the figure of the Virgin to her Son is symphonic in the physical mannerisms and colors used. Modestly and with great tenderness, she looks at Him indirectly with a dreamlike gaze. The eyes are large and wide-open. It's possible the angle of her eyes is directed down and to the right, looking in the direction of the viewer. The eyes actually seem to be rotating to the right, with the far eye looking further away, creating a living motion. It draws your own eyes in that direction. It's another subtle variation.

On the head of the Theotokos we can see a four-lobed star. There were originally two more in lost parts of the mosaic. The three stars symbolize the fact that the Theotokos was a virgin before Christ was born, during the time she bore him in her womb, and finally remained a virgin throughout the rest of her life.

Her maphorion has a gold embroidered edge around her face. This has been intentionally picked out. The restorers in the 1930's filled the missing parts with white plaster that was then toned in to match surrounding colors. At some point a clumsy attempt was made to restore the gold line with weird gold painted 'cubes'. The gold paint has decayed and looks bad. It would be better to restore the line with real gold mosaic. There are thousands of loose gold tesserae in the storerooms of Hagia Sophia today. There would have been another gold band around its bottom where it draped over her arms. There would have also been gold fringe attached to this lower band.

One can imagine the epigrams that would have been written describing the Theotokos. There are no written references to the Deesis from Byzantine times that have come down to us. But we can be sure they existed; the court of Manuel I was famous for its poets, who documented all of the major events and accomplishments of his reign - including works of art like the Deesis. Surviving histories tell us about the great murals in mosaic and paint depicting the glorious events of his reign that he commissioned to be put up in his palaces. One entirely new building he built was a huge new Throne Room he erected in the Great Palace. It was decorated with beautiful marble revetment, precious columns and vast, glittering mosaics glorifying the Comnenian dynasty, which showed Manuel being blessed by Christ Himself in the apse.

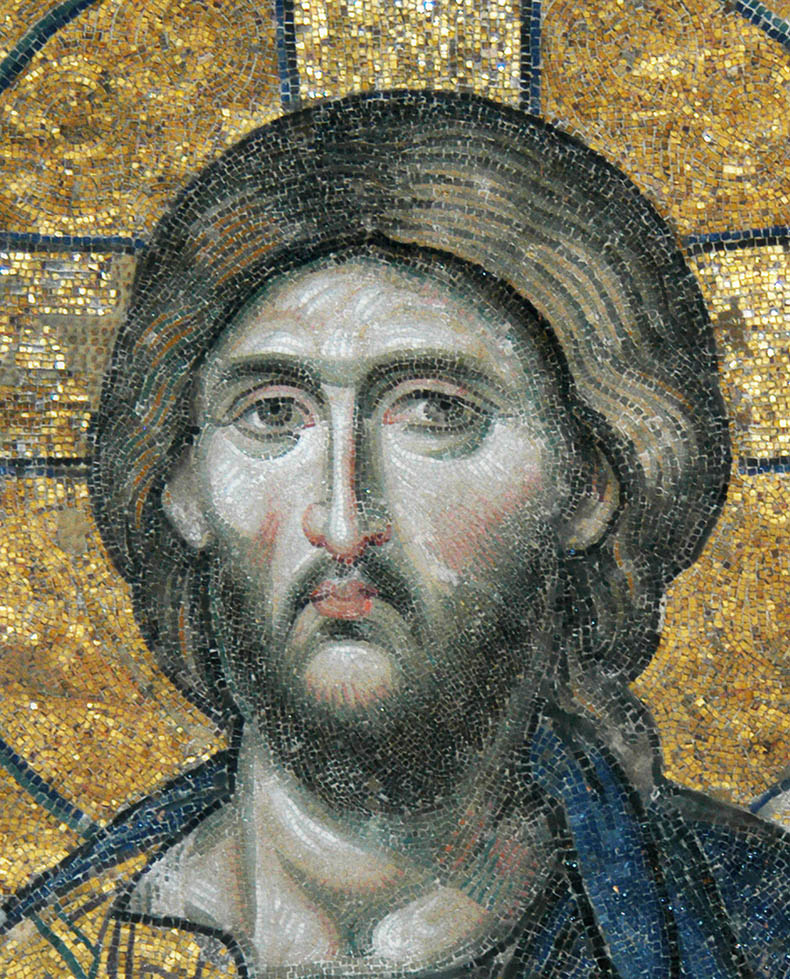

Eyes and Blessing Hand of Christ Mysteriously Follow You

The figure of Christ is extraordinary. His eyes and hand of blessing seem to follow you as you walk through the South Gallery and the effect was intentional. The hand has been set far to the right, almost centered below His eyes. The face has been foreshortened to be seen at an angle. That is why the eyes are of different sizes when viewed straight on. This vanishes if you look at Christ from the center of the Gallery.

Although the figures in the Deesis and the layout are conventional, the figures, the throne, the footstool and the background were a unique artistic creation. It was intended to be an active participant in the Imperial processions and ceremonies performed here. Christ was believed to be present spiritually and physically, a powerful presence that is, the same time, both human and divine - without division. Any Orthodox believer would understand this. Even the common man or woman in the streets of Constantinople knew the doctrines and teachings of the church on the nature of Christ and His sacrifice for humanity. The highly literate and sophisticated clergy of Hagia Sophia participated and helped plan the ceremonies and the art in the church. One might see the Deesis as a the creation of an elite culture that has come and gone long ago, but its beauty is something timeless. Anyone could appreciate, even without understanding its history and religious meaning. The Deesis is a unique masterpiece of religious art and one of the greatest accomplishments of European civilization.

Finest Mosaic Portrait of Christ Ever Created?

The face of Christ is amazingly alive and is composed of thousands of tiny mosaic bits that merge into one. This is perhaps the finest mosaic icon of Christ ever created and it is nothing short of a miracle that it has survived. There are many curious Byzantine conventions in the face that vanish because the face is so vividly alive. We are convinced this is really Christ and that He is present here. His golden robe shimmers and dissolves at the same time it feels tangible and touchable. His blue cloak is a rare and daring shade that is both precious like an enameled Byzantine icon and yet feels soft like wool - two conflicting impressions.

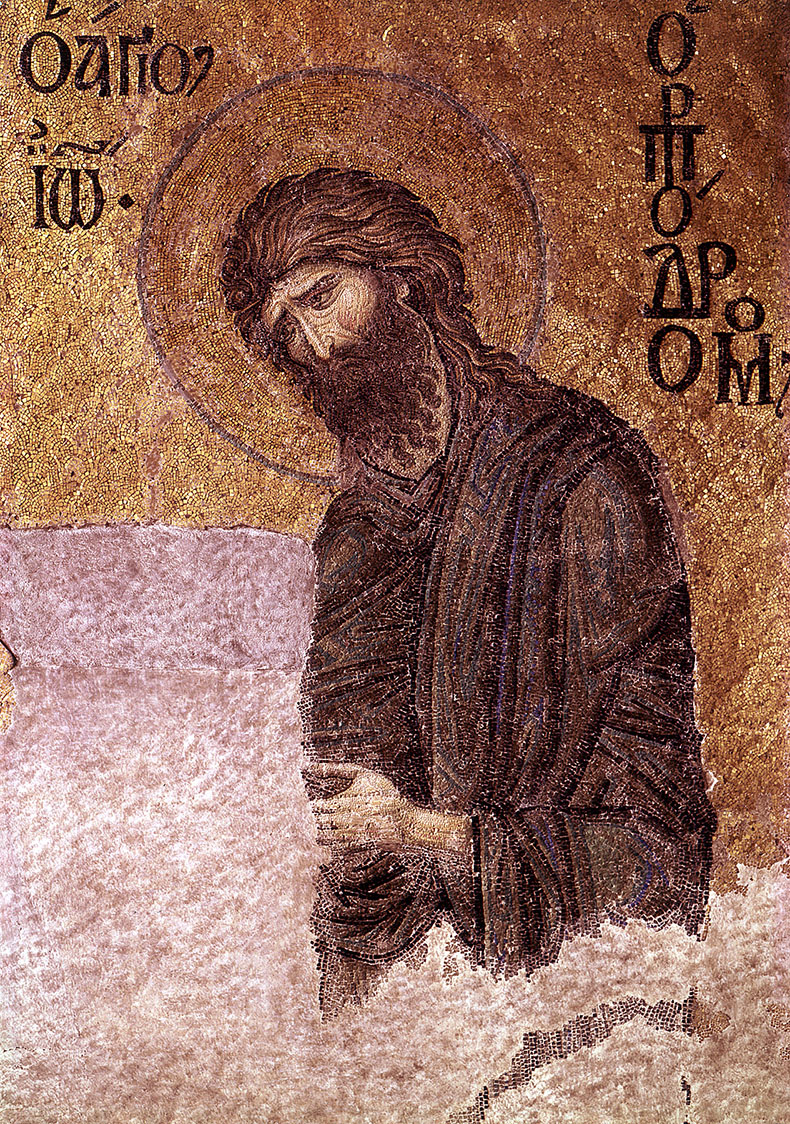

Figure of John the Baptist

The figure of John the Baptist is very life-like and it feels like he is about the step right off the wall. The face has the same number of small mosaic pieces as used in the Theotokos and Christ. The figure somehow feels very different that the other two, because of this some scholars who studied the Deesis felt it was a later addition to the panel. The drapery and the clothes of John have an amazing number of colors in them that blend together from a distance. Its unfortunate that a large part of the figure on the left side survived into the 20th century and was destroyed when the wall was opened up to check the cracks in the pier. A part of the Virgin's halo and robe that is now missing also survived up until the time of Fossati made his watercolor of the Deesis in the mid 19th century. This area was always prone to water damage from the window, even when it was covered with plaster.

Golden Background and Halos

The gold background was laid from top to bottom in bands by multiple artists. The pattern was laid free form without mechanical tools or templates. There is considerable improvisation, which would have made the work of laying the background less tedious for the workers. The overall pattern is of single and three lobed tiles. The larger, three lobed tiles are filled in horizontally and vertically. The single lobes are filled in by curved lines of tiles. The outlines of the lobes are set to reflect the light in a unique way, which creates a texture. The three lobed tiles resemble fleur-de-lys. Some of the gold cubes have been intentionally set backwards. In a few places silver cubes have also been used in the background. This was a technique Byzantine mosaic artists used to tone down the gold and focus the eye properly. It's probable that the background was laid by less skilled artists, possibly apprentices. There were three people working on the background at a time, every lobe took around 15 minutes to lay. They were working fast because they had to complete their work before the plaster bed set.

The artists who were creating the faces - three of them - must have been been working at the same time the background was being laid. It would have been easy to have six people working on top of the scaffold at a time.

The background is electric, its patterns reflect light in different ways that change as you walk around the panel. The light also changes based on the time by the hour. These changes in lighting can be quite dramatic and sudden. This side of Hagia Sophia faces south and gets a maximum amount of light. These patterns are laid in a lumpy way which makes the surface glow like cloth of gold shot with shiny gold thread. It is a like a woven gold silk backdrop that has been draped behind the figures. One can see a parallel in the golden jeweled veil that hung between the gilt-silver columns of the ciborium over the great altar in the sanctuary below. Also, at the time our mosaic was made there was a technique of monochromatic pastel silk weaving that depended entirely on light and movement to show its shimmery patterns. It was very popular and the material was used in clothes and drapery. The effect cannot be appreciated in photographs of these historic fabrics and hence they are not well known today.

The imperfections and subtle variations in the design of the background add vibrancy and surprise to the light. It is something that can only be experienced in person in front of the mosaic watching it change and flash. This technique of laying the gold mosaic was a deliberate, bravura effect that shows off the skill and creativity of the artists. It also tells us something about the luxury and sophistication of 12th century Byzantium.

The halo of Christ is set in almost invisible swirls in rinceau patterns. Only the image of Christ has these in His halo. It is meant to imitate in mosaic a technique used in icon painting. Painted icons and manuscripts with decorated patterns in halos developed independently and much earlier in Byzantium than examples in Italy. The Byzantines didn't punch their halo designs into the gesso like the Italians did, they were laid over the gold with a honey size and then gilded a second time. This technique is still used today in icon painting. The halos in the Deesis of all three figures are outlined in two rows of glass mosaic of different shades of blue. The icon of Christ has crossbars in its halo are set in straight rows laid at an angle to reflect light down. It seems to have been set freehand, without a template, since there are variations in the pattern throughout the panel.

South Gallery Was Separate from the Rest of Hagia Sophia

Because the South Gallery was closed to the public the Deesis was not as well known as it might have been. As mentioned earlier, there are no written records or pilgrim accounts to fill us in on the history of it or any special meaning people of the time saw in it. This is true of the other imperial mosaic panels here of Constantine and Zoe, and John II Comnenus, Irene and Alexios their son.

How to Make a Byzantine Mosaic - Completed in One Summer?

The Deesis must have been completed in one summer season, from May - September, since there were two undercoats of plaster that had to dry before the final layer was applied on which the mosaic was set. The two under-layers were pretty straight forward. The first layer contained crushed brick, lime dust and chopped straw. The second layer was finer and upon this layer rough outline of the design of the mosaic was painted. The plaster on the Deesis panel was finely done with large trowels and has some variation in it on purpose. A slightly uneven surface would reflect gold mosaic in a lively, glittering way. When Justinian built the church in the sixth century the plaster work was fast and a bit sloppy - they had huge areas to cover - imagine the vast vaults to be done - in gold mosaic and not much time to get it finished. The uneven surfaces and joins of Justinian's time have given those mosaics a much admired, but unintended shimmer. It was much easier to lay plaster on a flat surface and fortunately, that's what our workmen had to cover here in the South Gallery. The same plastering method is found in Byzantine churches from Greece to Italy, Russia and Georgia. This technique remained the same for almost 800 years, until the end of the empire. Below you can see an example of the layers from a 2013 video from the Art Institute of Chicago.

Making Mosaics - Workshops and Materials of Glass Production

As mentioned previously before the mosaic artists began work, a huge number or mosaic tesserae had to be assembled in various colors according to hue and intensity. Each color might have several shades. Cubes were made of stone and glass. The stone tesserae included some cubes of semi-precious stones, such as lapis lazuli. However, it was the glass tesserae that had the strongest and most brilliant color combined with the subtle effects of light penetrating the cubes or reflecting off of their glassy surfaces. The gold cubes used in the background were thinner than those used in the figures, book and throne. They were made using a special process. First, the slag glass was heated, laid on a table and then flattened into great round slabs of glass with pieces of wood. Then a very thin (almost transparent) layer of gold was placed between two layers of glass and fused together, like a sandwich. The thin top layer was made in an aqua colored glass. The transparency of the god layer is worth noting. It allowed light to pass through it, hit the back of the cube and then reflect it back from the white plaster setting bed, which makes these cubes have a special, golden glow. After fusion of the layers the slabs were carefully cut into cubes. It is possible to tell where a cube was cut from these disks by its shape. Mosaic cut from the edges has a curved edge. The composition of glass changes based on where the slag glass comes from. Chemical analysis shows that all of the 12th century gold mosaic came from Constantinople. The slag glass comes from Syria. From shipwrecks we know that glass merchants transported massive quantities of raw slag and used glass from port to port, ending in Constantinople to satisfy the demand of its glass factories.

In the Deesis we find a combination of old and new gold mosaic. Before the Deesis there had been another mosaic here that was taken down. They saved the mosaic from it and reused it, so a significant amount of mosaic in the panel is 6th century and already 500 years old. When mosaic ages the top layer of glass placed over the layer of gold can peel off. This continues to happen and presents a problem, should old cubes that decay we replaces - or should they be allowed to darken and loose their luster? The colors in the gold ranged from a deep glowing yellow to a bright lighter sunny shade. There were also a smaller number of cubes in red and white gold. These variations are caused by the various colors of glass under which the gold leaf is laid, and sometimes by paint applied under the tesserae which shows through the glass. In the background of the Deesis, silver is also found. Great care was taken with sorting and planning of the ratio of different types to be used. Had the entire background been of one type of gold it would have looked cheap and garish. Our artists were experts at using various types of gold tesserae to create the best looking background with dazzling effects embedded in it. Below are two screen captures from the Art Institute of Chicago showing how the Byzantines made glass mosaic cubes. The Master Mosaicist is Matteo Randi. Our 12th century artists would have made adjustments to cubes this way, right on the job.

In the middle ages Byzantium was one of the most important producers of glass. Constantinople imported slag glass from the middle east that was processed in the city. These factories produced tons of mosaic a year, which was exported throughout the empire, Western Europe and the Middle East. There was a luxury market for glass that was produced to the highest artistic and technical standards, combining, color, enamel and gilding. The Imperial court was the primary customer for these items like glass beakers and serving dishes, which were used in the palaces and given as gifts. Most of Byzantine glass production was commercial, making glassware intended for everyday use in homes and businesses. Even an average middle-class Byzantine could afford small jewel-like perfume bottles and jars for cosmetics. Beautiful glass bracelets have been found all over the empire - and abroad - which indicates their popularity. Replicas of carved gemstones of Christ and the saints were made in cast glass for the mass market. Vast numbers of glass lamps were needed every year to light houses, palaces, streets, shops and churches. Also, Byzantium produced both pane and bottle glass for windows. All of these things would have been sold through retail shops in the city.

In the middle ages Byzantium was one of the most important producers of glass. Constantinople imported slag glass from the middle east that was processed in the city. These factories produced tons of mosaic a year, which was exported throughout the empire, Western Europe and the Middle East. There was a luxury market for glass that was produced to the highest artistic and technical standards, combining, color, enamel and gilding. The Imperial court was the primary customer for these items like glass beakers and serving dishes, which were used in the palaces and given as gifts. Most of Byzantine glass production was commercial, making glassware intended for everyday use in homes and businesses. Even an average middle-class Byzantine could afford small jewel-like perfume bottles and jars for cosmetics. Beautiful glass bracelets have been found all over the empire - and abroad - which indicates their popularity. Replicas of carved gemstones of Christ and the saints were made in cast glass for the mass market. Vast numbers of glass lamps were needed every year to light houses, palaces, streets, shops and churches. Also, Byzantium produced both pane and bottle glass for windows. All of these things would have been sold through retail shops in the city.

Returning to the making of mosaics, once the plaster had dried and set properly, work began on the topmost layer of lime and marble dust where the mosaic cubes would be set. This fine layer of plaster was applied in a patchwork of sections just large enough to be completed in one day's work. The plaster joins were easy for the restorers to see and record. It gave them a good understanding of how the mosaic was created. On this layer a detailed colored painting was prepared as a guide for the artists.

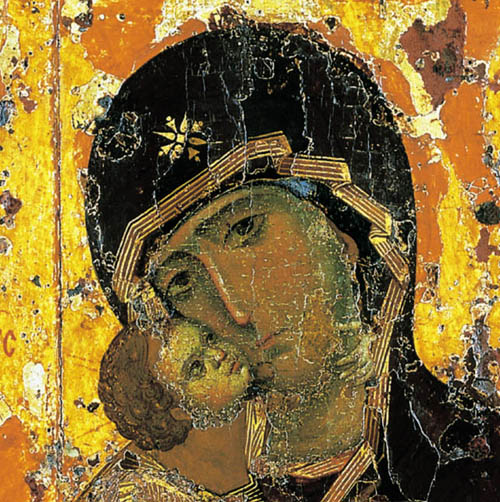

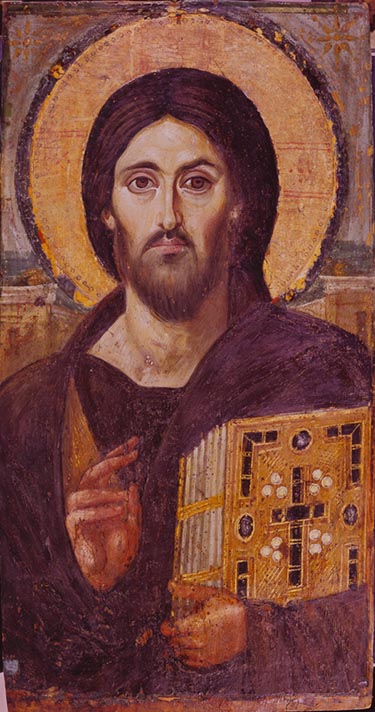

As a comparison to the Theotokos of Hagia Sophia, here is a close up of the Kahn Madonna from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.. One can see the same almost excessive attention to graduated color and subtle shadow transitions in the Virgin's face. This is an example that typifies the essence of 'tenderness' icons which were popular in Byzantium in the mid-twelfth century and were exported across Western Europe and Russia. Works like this had a great influence on Italian artists like Duccio. Below it is a close-up of the famous Virgin of Vladimir, which was painted around the same time the Deesis was created.

As a comparison to the Theotokos of Hagia Sophia, here is a close up of the Kahn Madonna from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.. One can see the same almost excessive attention to graduated color and subtle shadow transitions in the Virgin's face. This is an example that typifies the essence of 'tenderness' icons which were popular in Byzantium in the mid-twelfth century and were exported across Western Europe and Russia. Works like this had a great influence on Italian artists like Duccio. Below it is a close-up of the famous Virgin of Vladimir, which was painted around the same time the Deesis was created.

Many Byzantine paintings and mosaics were done with stencils made from other works. This ensured that each icon was true to its prototype and could be trusted to be a true representation of the saint depicted. In some cases a talented and experienced artist could work directly on the plaster without preparatory drawings - but this was very rare and discouraged by some artists as reckless.

We don't know anything for sure about the artists that created this mosaic. Were they monks from a monastery in Constantinople? Were they workers from an atelier in the city that was attached to or patronized by the Imperial court? Were they artists engaged by the patriarch brought in from provincial cities of a distant part of the Empire? I think we can conclude they were one of many workshops working in the city. This workshop was probably centered in a single family expanded through marriage, composed of masters and apprentices. These workshops developed their skills from generation to generation as they worked on specific projects. They produced mosaic programs based on prototypes they were given to work with. They would have produced both secular and religious works. Prototypes could be taken from manuscripts and other mosaic programs done in Constantinople over hundreds of years. From a technical standpoint there were many styles to learn from first hand. There were many beautiful classical secular mosaics all over the city to serve as learning tools and models. It is possible to follow the work of one workshop that produced the mosaics for many of the churches of Greece in the 11th and 12th centuries. They were extremely versatile and worked in completely different styles - like Hosias Lukas and Daphni. This workshop may have also worked in Torcello in Italy which shows how far they could move. They could have have been a part of the great mosaic project commissioned and paid for by Manuel at the Church of the Nativity in Bethelem. As mentioned earlier these mosaics could be completed quickly and one workshop could produce a large number of projects in a few years time. The production of mosaics was very different from fresco painting, but a mosaic workshop would have been expected to produce paintings, too.<

Many Italian families had multi-generational relationships in Constantinople as merchants and property owners. In the 12th century an Italian could could contract with mosaic workshops in Constantinople to travel to their country and decorate churches and private buildings. You could also find representatives of these workshops in already working in Italian cities and order work from them there. There were free-lancers - like Mark the Greek in 12th century Venice - who are found working independently. The Imperial government in Constantinople seems to have had no interest in impeding contacts between foreigners and Byzantine workshops, which must have been very profitable. Orders were also placed for things like gilt-silver covered icons, church doors made of leaded brass and inlaid with silver, chandeliers, glass lamps and silk curtains. You could get anything you wanted in Constantinople buying it from in stock supplies or place new orders. Besides mosaics you could also find artists to make inlaid marble floors. There must have been some trade in columns and marble revetment as well. All of this was made possible by the huge number of craftspeople involved in these trades, the ability to transfer funds to pay for these things and the availability of ship transport. Mosaic projects involved not only the transport of glass tesserae, but the artists and workers who prepared the plaster beds and laid the mosaic. Since mosaics could only be laid in late spring and summer, the same artisans could be making inlaid marble floors in fall and winter. In Sicily there were a large number of huge church projects that were done back-to-back. It's possible the same workshop was employed for more than one project and the workers stayed for years there. They could have brought in locals to help get the jobs done and thus passed on some of the skills they brought with them. It's also possible that different crews came from Constantinople and were working independently there.

A huge amount of glass mosaic - tons of it - was required for every project and could be newly produced quickly in specialized workshops around Constantinople. There was a constant need for acres of gold mosaic which if wasn't newly made could be harvested from ruined or abandoned churches. Special permission was required to remove mosaic (or any other building materials) from a ruined building. Mosaic could have been ordered by the job and/or stored in advance in warehouses. These warehouses could have been private enterprises or run by Imperial officials. They could have been attached to the workshops themselves or to churches. Glass being a delicate material transport was easiest by ship, but great care must have been taken to arrange to move the glass from dockside to the building site. Stone and marble mosaic could be produced locally from available sources. This would have eliminated transportation costs and the risks involved in it. By the end of the 12th century Venice was able to produce all of its mosaics locally through its own workshops. It began to produce its own glass mosaics as well and had no need to import Byzantine craftsmen. They created mosaics from their own programs that were planned in Venice itself. All of the mosaics workshops and glass factories in Constantinople were was lost in 1204. During the Fourth Crusade they were either destroyed by fire or abandoned as their workers fled the city as refugees. Most refugees fled the city in family groups, so its possible workshops may have been able to carry their skills into exile, however it is unlikely they had access to the storehouses of materials left behind in Constantinople. The Latin Crusaders who pillaged the city would have sold off any troves of glass and mosaic they found. the Venetians would have been especially interested in them as raw materials. In 1261 when the Byzantines recovered their capital city there would have been nothing left and they would have had to assemble their mosaic from scratch or take it from the many ruined buildings.

Daily Life in 12th Century Constantinople

In the middle of the twelfth century, when our mosaic was created, Constantinople was packed to the gills with 400,000+ people. The population had not been this big since Justinian's time when the plague wiped out two thirds of the population in three months time. The growth in population was a result of the expanding economic activity and increasing wealth of the empire during the Comnenian Dynasty. It was also a result of immigration from Asia Minor as people fled the advancing Turks. Much of the wealth of the Byzantine Empire was now generated by the huge consumer market the city had created and the surrounding businesses, farms and fisheries that supplied it. The main trade consisted of the day-to-day need to housing, clothing and feeding of almost half a million souls. This trade financed the Imperial court. One thing that set Constantinople apart from other cities were her luxury industries, like the manufacture of fine fabrics, gold-working, glass, perfumes, books, furniture and works of art. While these trades focused on the rich and elites of Constantinople, every home had its own - if more humble - furnishings. This 'middle-class' market was a huge one. For the standpoint of art every Christian household would have proudly owned and piously displayed at least one icon. The glinting gold and bright colors of these icons would have given their owners a bit of luxury and beauty, no matter how poor they might be. Most of these icons were inexpensive; one icon was equal to the cost of a good pan.

Beyond icons, the common people had an appreciation for non-religious art, since they were surrounded by secular works from ancient Greece and Rome in the city's forums, squares, colonnaded streets and the famous Hippodrome. There were hundreds of churches and chapels crammed with beautiful things that people saw everyday. Even so, we can't forget how filthy Constantinople was in the late 12th century and the terrible juxtaposition of wealth and poverty to be seen everywhere. This was one of things that struck people who visited Constantinople in this period. Homes in Constantinople had evolved from Roman style apartment buildings and courtyard houses. You could find fine nobles living in palaces -- right next door to five-story tenements of incredible squalor. The smell at ground level would have been dreadful, all of the sanitary facilities were on the ground floor. When more people were added to a building there was no way to add more toilets. Wealthier people lived on the top floors, but they still had to climb down to the ground floor to use them.

Most private homes in Constantinople were courtyard homes. There would be communal big dome ovens in them for cooking - especially the making of bread. These ovens required wood which was delivered directly to homes and building by commercial companies. Different kinds of wood and charcoal were used for different purposes. There were portable braziers kept on upper floor for warmth and to prepare small meals. As a highly developed urban society Byzantine homes had a wide variety of pots and utensils used in the preparation, storage and eating of food. Homes also had large tanks for water storage in their courtyards and smaller ones in homes. Water was brought to your door in wooden tanks for sale or extracted from wells. Many homes had direct access to cisterns - there were thousands of them all over the city.

In the middle of of this in spring and summer the city was covered with flowering vines, roses and fruit trees. Where ever there was a space to plant something people did. They filled their windows and balconies with beans, peas and flowers. If they living in a house with a flat roof the inhabitants would plant anything they could that could be harvested and eaten. People who were fortunate enough to live in a house with a courtyard could plant fruit trees, grape vines and even roses. In late summer parts of the residential areas of Constantinople would have the appearance of an urban jungle and all of this greenery could make life in the city more bearable.

Fires were frequent and an indicator of the decline in the quality of life as the city became more crowded. Before 1204 most of the private homes were built of stone and brick, in late Byzantine times - and throughout the Ottoman period - homes were built mostly in wood.

As more people moved to the city landlords built up - adding floors to existing buildings and dividing up great houses. Not a wise move when the additions were often constructed of wood and the streets were so narrow. The fires set by the Crusaders of the Fourth Crusade did more damage to the fabric of city than pillage. Vast areas were reduced to ashes and the fires marked the true end of the ancient city as its porticoes, shops and forums were destroyed. The fires came very, very close to Hagia Sophia and reached the edge of the atrium.

With so much to see in every quarter of the city, people took them for granted, although they could be very superstitious about this statue or that column, giving them supernatural powers over the fate of the city. The educated citizens of Constantinople cared about their history and the many famous and beautiful things to be found there. The Hippodrome was lined with dozens of statues, columns and other things the common people saw when they were at the races or games in the stadium. Sitting in the stands and crunching on snacks they would discuss the myths associated with the statues of men, beasts and giant insects which were placed along the spina - which ran down the center of the race track. No matter what your level of education or how rich you were Byzantines had a unique appreciation for art and beautiful things - especially when it was religious. They were also great followers of sport, fashion and stars of the theater.

In the late twelfth century, Constantinople must have had 10,000 icon painters competing for business. Although we can assume that there were lots of freelance artists, most painters would have been part of a workshop or attached to a monastery. Icons, both new and antique, were sold in shops, from street kiosks, and even by street peddlers. There must have been a staggering range in artistic quality when so many painters are involved. Among potential patrons of icon painters the Imperial Court and the Patriarchal Church would have been the most important. Every workshop and painter would have aspired to to work for them. Being an officially recognized painter could give an artist a level of protection, but you were only as good as your last icon. This is the eternal struggle of all artists - you can be famous one day and forgotten the next. No matter how good you think you are there is always someone better and cheaper competing for business. Icons could be created in cheaper materials to reduce their cost. Gold backgrounds could be substituted with cheap silver leaf which was then glazed in orange colored shellac to imitated gold. Icons could be painted on flat wood backgrounds instead of panels with hollowed out centers. Panels could be painted on cheaper woods (resulting in splits), be made of smaller pieces of wood glued together, or just made much thinner to save money on them. Painters could use cheaper pigments, too. One can assume that many Byzantine icons made for the mass market where produced in assembly line fashion, with one artist painting faces, another clothes and another doing backgrounds. Styles - even in icon painting - changed rapidly. Subject matter changed as well, pilgrims wanted icons of their own national saints, like Boris and Gleb for the Russians. The peddlers of icons who trolled the streets would also besiege potential customers inside and outside places like Hagia Sophia.

Fortunately for the 12th century Byzantine icon painter there were lots of of potential individual patrons with money. Many of them would have been people who knew artistic quality and fine technique when they saw it and would buy it when they found it. Below the Imperial court and the Patriarchate there were also wealthy nobles and rich monasteries who were knowledgeable patrons of art. There was also a business in the repair and restoration of old icons.

.

As the commissioner of the Deesis, he would have been expected to provide all of the materials for it. He would have picked the rare and expensive for the mosaic. There was an existing mosaic here, we don't know what it depicted. It might have been a huge plain gold field or had a non-figurative design from the era of Justinian. The emperor would have involved theologians, poets as well as the artists to discuss the purpose of the mosaic and what it was to convey. This spot was one of the most important in Hagia Sophia and the mosaic was intended to make an important artistic and religious statement. It was also intended to bring glory to the Emperor.

As the commissioner of the Deesis, he would have been expected to provide all of the materials for it. He would have picked the rare and expensive for the mosaic. There was an existing mosaic here, we don't know what it depicted. It might have been a huge plain gold field or had a non-figurative design from the era of Justinian. The emperor would have involved theologians, poets as well as the artists to discuss the purpose of the mosaic and what it was to convey. This spot was one of the most important in Hagia Sophia and the mosaic was intended to make an important artistic and religious statement. It was also intended to bring glory to the Emperor.

In the middle ages Byzantium was one of the most important producers of glass. Constantinople imported slag glass from the middle east that was processed in the city. These factories produced tons of mosaic a year, which was exported throughout the empire, Western Europe and the Middle East. There was a luxury market for glass that was produced to the highest artistic and technical standards, combining, color, enamel and gilding. The Imperial court was the primary customer for these items like glass beakers and serving dishes, which were used in the palaces and given as gifts. Most of Byzantine glass production was commercial, making glassware intended for everyday use in homes and businesses. Even an average middle-class Byzantine could afford small jewel-like perfume bottles and jars for cosmetics. Beautiful glass bracelets have been found all over the empire - and abroad - which indicates their popularity. Replicas of carved gemstones of Christ and the saints were made in cast glass for the mass market. Vast numbers of glass lamps were needed every year to light houses, palaces, streets, shops and churches. Also, Byzantium produced both pane and bottle glass for windows. All of these things would have been sold through retail shops in the city.

In the middle ages Byzantium was one of the most important producers of glass. Constantinople imported slag glass from the middle east that was processed in the city. These factories produced tons of mosaic a year, which was exported throughout the empire, Western Europe and the Middle East. There was a luxury market for glass that was produced to the highest artistic and technical standards, combining, color, enamel and gilding. The Imperial court was the primary customer for these items like glass beakers and serving dishes, which were used in the palaces and given as gifts. Most of Byzantine glass production was commercial, making glassware intended for everyday use in homes and businesses. Even an average middle-class Byzantine could afford small jewel-like perfume bottles and jars for cosmetics. Beautiful glass bracelets have been found all over the empire - and abroad - which indicates their popularity. Replicas of carved gemstones of Christ and the saints were made in cast glass for the mass market. Vast numbers of glass lamps were needed every year to light houses, palaces, streets, shops and churches. Also, Byzantium produced both pane and bottle glass for windows. All of these things would have been sold through retail shops in the city.

As a comparison to the Theotokos of Hagia Sophia, here is a close up of the Kahn Madonna from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.. One can see the same almost excessive attention to graduated color and subtle shadow transitions in the Virgin's face. This is an example that typifies the essence of 'tenderness' icons which were popular in Byzantium in the mid-twelfth century and were exported across Western Europe and Russia. Works like this had a great influence on Italian artists like Duccio. Below it is a close-up of the famous Virgin of Vladimir, which was painted around the same time the Deesis was created.

As a comparison to the Theotokos of Hagia Sophia, here is a close up of the Kahn Madonna from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.. One can see the same almost excessive attention to graduated color and subtle shadow transitions in the Virgin's face. This is an example that typifies the essence of 'tenderness' icons which were popular in Byzantium in the mid-twelfth century and were exported across Western Europe and Russia. Works like this had a great influence on Italian artists like Duccio. Below it is a close-up of the famous Virgin of Vladimir, which was painted around the same time the Deesis was created.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints