"The barons and the Venetians battered the walls and towers day and night without with various machines, and redoubled the War, conducting many great skirmishes from one area to another; it was in one of these that they valorously acquired the banner of the Tyrant, but with much greater joy a panel on which was painted the image of Our Lady, which the Greek Emperors had continuously carried in their exploits, since all their hopes for the health and salvation of the Empire rested in it. The Venetians held this image dear above all other riches and jewels that they took, and today it is venerated with great reverence and devotion here in the church of San Marco, and it is one that is carried in procession during times of War and plaque, and to pray for rain and good weather."

Giovanni Ramusio - 1559

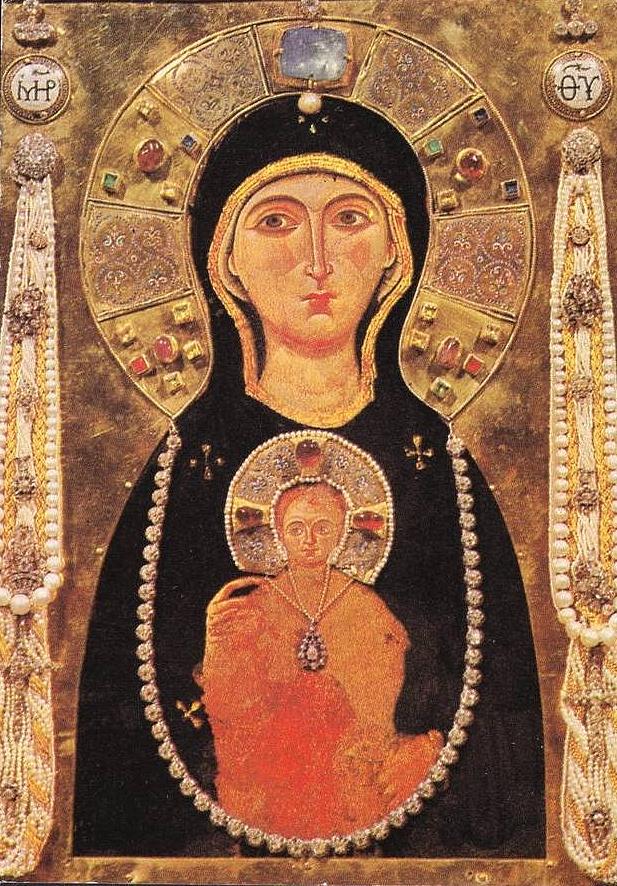

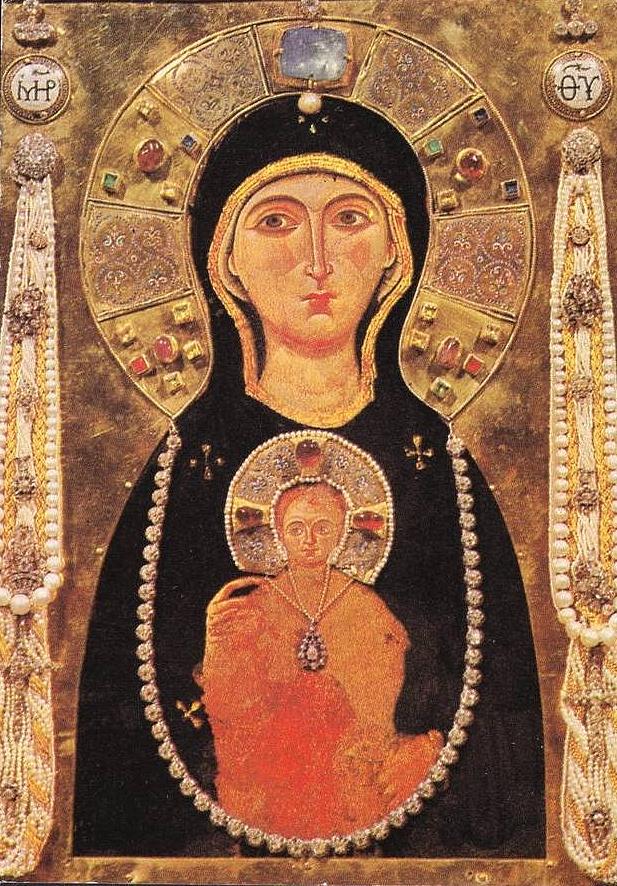

On the left you can see a picture of the icon before the robbery. Missing are strands of pearls that hung from the round hooks on either side under the initials. You can see the jewels today which are displayed in the Treasury of Saint Mark's.

On the left you can see a picture of the icon before the robbery. Missing are strands of pearls that hung from the round hooks on either side under the initials. You can see the jewels today which are displayed in the Treasury of Saint Mark's.

This icon is of the same type seen in the mosaic of John II Komnenos and Eirene. It measures 58cm x 55cm - 22 x 23 inches, almost square. There are 16 Byzantine enamels on the frame. It was moved from the sacristy of Saint Mark's to the current chapel on the left side of the church in 1618.

This image of the Virgin was closely associated with the Imperial throne and was believed to be a source of its power. The icon is in an original Byzantine frame of gilded silver with gold enamels, pearls and gemstones, the enamels have been re-arranged. The surface of the icon and the figure of Christ was badly damaged by the attachment of jewels and pearls to the icon by Venetian devotees of the icon which rubbed against the surface of the icon. Later the robbery caused more damage when the jewels were ripped from the icon. However, the face of the Virgin is very well preserved and shows extreme delicacy and refinement in the the painter's technique. It was probably created in the early 12th century, specifically to follow the emperor and the army on campaign. Perhaps it was made for John II himself, who spent most of his reign in the field, fighting the empire's many enemies. This icon was greatly esteemed by him and his family.

John and his wife, the Hungarian Princess Eirene, had eight kids, four boys and four girls. They all traveled with him as a family unit. Three of the boys followed in the footsteps of their dad and became soldiers. One boy became an artist and scholar.

The eyes of both the Virgin and Christ look to the left, this indicates the icon was stood on the right side of the entrance to the Imperial tent or the door to a sanctuary or chapel. This icon traveled with John II and his family throughout his military campaigns. It would have been displayed alongside Imperial banners and flags on poles which also carried images of saints and angels for the troops to see and venerate. At night the icon would have been brought inside the gigantic Imperial tent and placed in a private chapel for John, his family and the top army officers. The icon had it's own attendants and priests. For John and his soldiers the icon symbolized the Art of the Covenant which traveled with the ancient soldiers of God and was on display in the Temple of Jerusalem. This icon had the same power to bring victory to the Christian empire as it did for Israel.

Members of the imperial family embroidered veils which were set with pearls and jewels to cover the icon when it was not on display. The icon traveled on the gilded Imperial galley when it crossed the sea.

When John returned to Constantinople for a parade celebrating a military victory he gave up his gold, silver and ivory chariot and had the icon placed in a kiot that stood in his place. During the parade tens of thousands of Byzantines lined the route, the road was covered in myrtle, grape leaves and rosemary. Tapestries hung from windows and balconies while choirs sung hymns to Christ and His Mother, The air was fragrant with incense that was burned in silver censors swung by white-robed deacons. Following the chariot on foot was John and his family along with all of the banners of the military, the guilds of merchants and noble families of the city.

The victory john was celebrating was the recapture from the Muslim Turks of the ancestral castle of the Komnenian family, Kastamon. John believed the Virgin was personally responsible for this important victory. Sadly, just a few months later the Turks retook it. This was a personal and public humiliation for John. He must have found it difficult to understand why the Theotokos had taken away his victory. John would have searched his soul for something he had done wrong.

John was succeeded by his youngest son, Manuel, who continued his father's devotion to the icon. It followed him throughout all of his campaigns, too. John believed the Virgin spoke to him and gave him direction, Manuel believed Christ fulfilled the same role for him.

On the right is another image of the icon before the robbery with the pearls.

On the right is another image of the icon before the robbery with the pearls.

The icon was taken by bloodied Crusader soldiers in 1204 in hand-to-hand combat with the defenders of the city at the Pantepotes Monastery which was and the last stand of the Byzantines. In the end the defense of the city had been taken on by a ragtag army composed of common people led by a few young aristocrats that had hastily been organized at Hagia Sophia. Refusing to fight without payment in gold, the Varangian Guard stepped aside and let the Latin troops ravage the city at will. The icon was taken as war booty by the Venetians and sent to Venice as a trophy. It was a symbol that God had now transferred His blessing from Constantinople to Venice by force of arms.

The crusaders had been blessed by the Catholic church and allowed to rob and rape at will because the Byzantines were heretics and not Christians, Murdering them was not a sin and would be blessed by Christ Himself. Killing them was required. The looting of the churches was also justified as restoring their treasures to the true church. Catholic bishops, priests and monks followed the Latin soldiers as they looted Constantinople, making deals for relics and having the soldiers do their dirty work of despoiling sanctuaries.

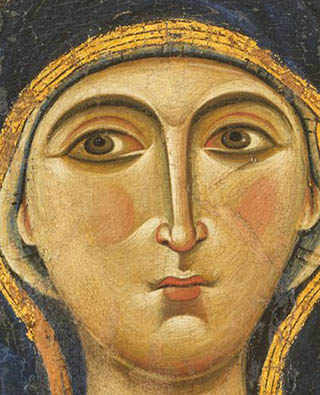

The Nicopeia was meant to be seen from a great distance and in low light. As an Imperial commission it is painted in an extraordinary fine technique and was produced in the finest icon painting studio in the city. Perhaps a workshop connected to the Kokkinophatos manuscripts. This workshop was responsible for the official images of John and his family, which were reproduced hundreds of times for the court and in public buildings. The mosaic of John II and Augusta Eirene in Hagia Sophia was designed by this studio. You can see more work of the workshop in the family Gospels of John II.

There are a number of subtle effects that people of the time would have noticed and appreciated in this icon. The whites of the eyes are strong and bright, the eyes, eyelids and eyebrows are all drawn with great confidence. Highlights in the face are sharp and bold. If you stare at the face it almost becomes alive; you can almost hear the voice of the Virgin speaking to John through it.

I am not sure why the beautiful halos were left off in the restoration. The icon would be much more attractive - and look less battered - with them. The outline of the Virgin has been greatly altered by later regilding. Now the head is smaller and the shoulders are too rounded.

The Venetians hug jewels and ropes of pearls on the icon itself, while the Byzantines used silk veils embroidered with gold thread.

The great silver-gilt, gold cloisonné and jeweled halos (long with the magnificent cover) were removed from the icon during its restoration. I assume the experts determined they not original to the icon. However, they were very pretty and appropriate - in my opinion the icon looks barren without them. They appear to be Byzantine and could have been added to the icon from other looted treasures from Constantinople.

In February 1438 a large delegation from Constantinople arrived in Venice headed for for a great church council negotiating the union of the churches that was held in Italy. The ancient Patriarch Joseph II along with a group of clerics and nobles visited Saint Mark's and saw the treasures that had been looted in 1204. Here is an account of the visit:

The objects there were very precious and very rich indeed, studded with priceless stones of exceptional size and clarity. There were also numerous sacred figures made of different materials, all of extreme quality and refinement. Some were carved in stone with great skill, others were made with great taste from the purest gold. We also looked at the divine icons from what is called the holy templon, radiant in their golden shine and overwhelming the onlookers with the number of their precious stones, the size and beauty of their pearls, and the sophistication and diversity of the arts employed. These objects were brought here according to the law of booty (νόμῳ τῆς λείας) right after the conquest of our city by the Latins, and were reunited in the form of a very large icon on top of the principal altar of the main choir. Its mighty doors opened only twice a year, on the Nativity of Christ and the holy feast of Easter. Among the people who contemplate this icon of icons, those who own it feel pride, pleasure, and delectation, while those from whom it was taken — if they happen to be present, as in our case—see it as an object of sadness, sorrow, and dejection. We were told that these icons came from the templon of the most holy Great Church. However, we knew for sure, through the inscriptions and the images of the Komnenoi, that they came from the Pantokrator Monastery.

Old and blind, Doge Dandolo died in Constantinople in 1205. He would have immediately dispatched the icon to Venice as the most important trophy of the destruction of Constantinople. It was a symbol of how the balance of power had just moved from Byzantium on the Golden Horn to the lagoons of Venice.

The image below is a 16th century copy of the icon that is now in the National Museum of Ravenna. It shows the position of Christ, His body and the hand of the Theotokos, which is holding a linen napkin.

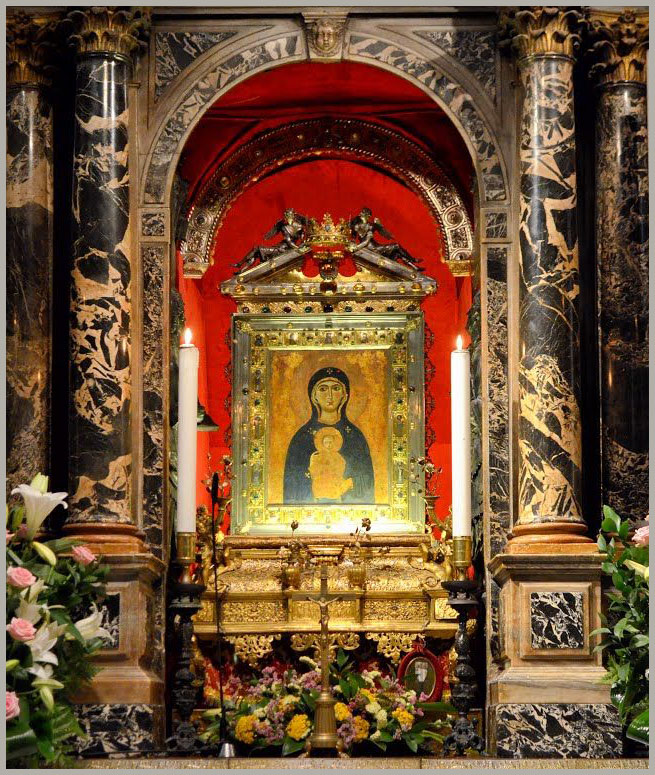

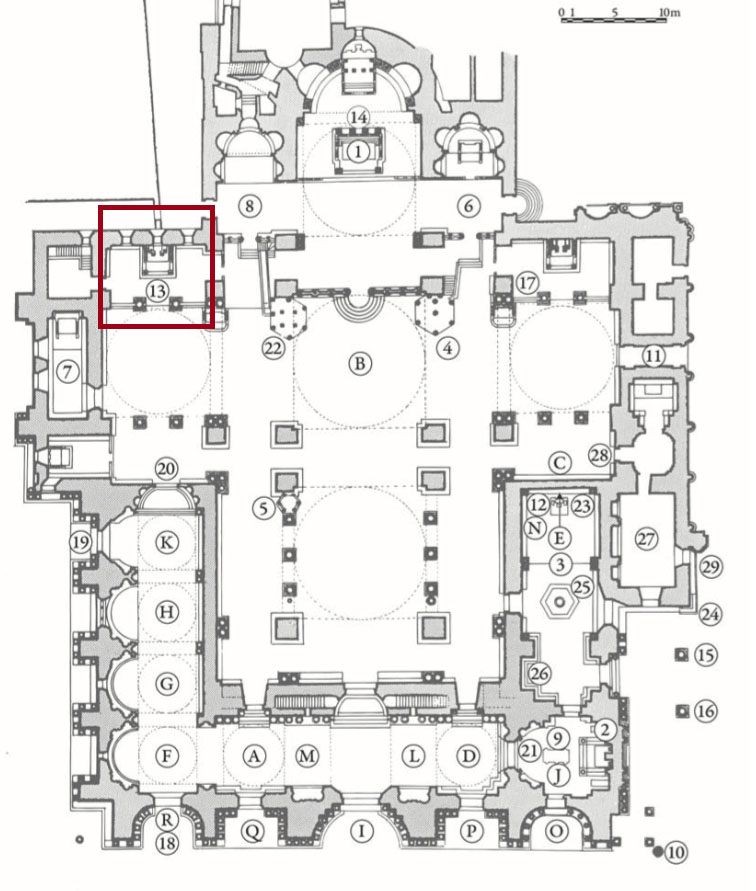

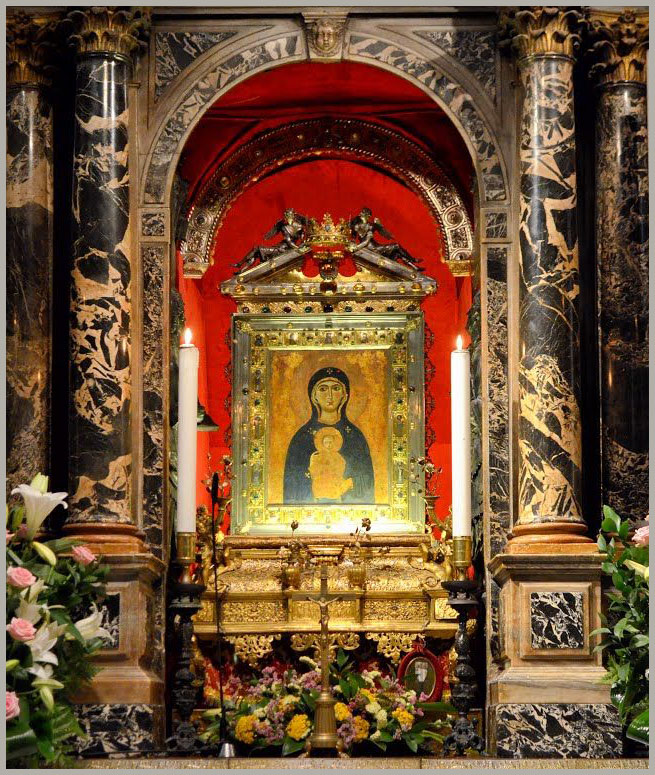

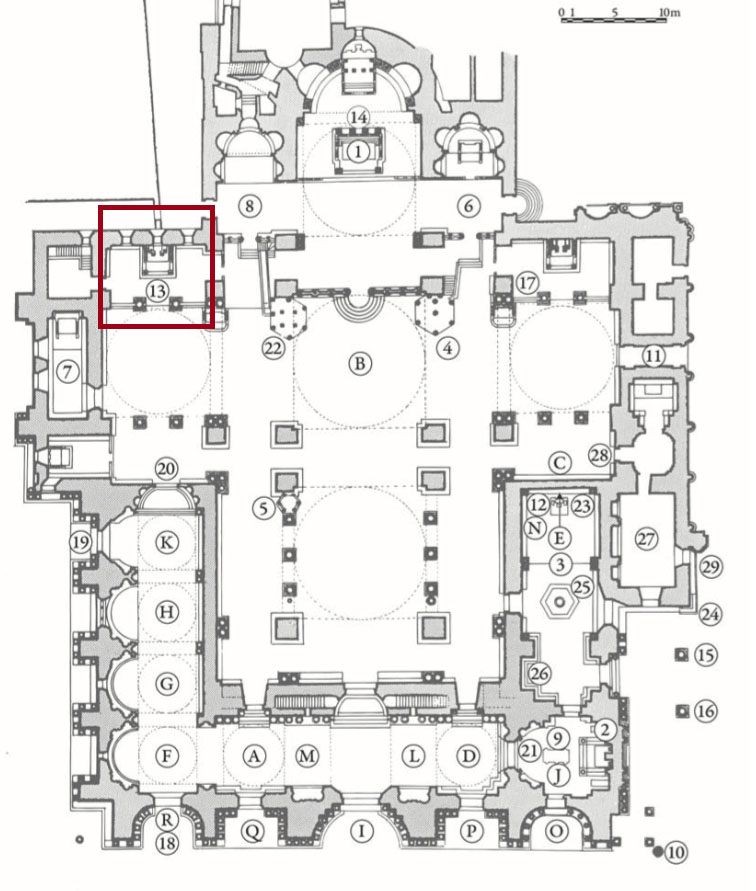

Below the picture is a map showing the location of the icon in Saint Mark's marked with a red box

Above you can see the elaborate shrine built to house the icon in Saint Mark's in Venice. A stand like this is called a kiot in the Orthodox world.

Above you can see the elaborate shrine built to house the icon in Saint Mark's in Venice. A stand like this is called a kiot in the Orthodox world.

On the left you can see a picture of the icon before the robbery. Missing are strands of pearls that hung from the round hooks on either side under the initials. You can see the jewels today which are displayed in the Treasury of Saint Mark's.

On the left you can see a picture of the icon before the robbery. Missing are strands of pearls that hung from the round hooks on either side under the initials. You can see the jewels today which are displayed in the Treasury of Saint Mark's.

On the right is another image of the icon before the robbery with the pearls.

On the right is another image of the icon before the robbery with the pearls.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints