he struggle which Theodora had foreseen was not long deferred after her death, and Michael Stratioticus was compelled, after a few months of feeble imperial experiment, to retire to the private life from which he had been unwisely drawn. The great territorial nobles—one might almost say, the feudal nobles—concentrated upon the capital and put one of their number, Isaac Comnenus, upon the throne. Isaac had in earlier years married a Bulgarian princess, and her career as mistress of a large provincial domain, and then as Empress of Constantinople, suggests a very interesting study. Unfortunately, her husband’s reign lasted only two years, and the events yield us only few and fleeting glimpses of the new Empress.

Æcatherina, as the best contemporary authority, Nicephorus Bryennius, calls her (though later writers often say Catherina), descended from the Bulgarian royal family, which had fallen from its high estate when “Basil the Bulgarian-slayer” had won a definitive victory over the nation. Bryennius makes her a daughter of the King Samuel, and we have in a later chronicle a picture of Samuel’s daughters which would dispose us to imagine Æcatherina as a very fiery and interesting personality. When, in the presence of Basil, they were brought face to face with the woman whose husband had killed their brother, the Emperor and his officers had great difficulty in preventing a very violent and undignified scene. The dates, however, make it improbable that Æcatherina was one of the daughters of Samuel—others more probably suggest that she was his niece, or182 grand-niece—and in character she seems rather to have been gentle and religious. She was brought from her remote provincial home and made Augusta, but she proved to be one of the quiet and retiring Empresses who leave no mark in the chronicles. The only reference to her is that, in 1059, she encouraged her husband, who had met with a serious accident or illness, to resign, and she herself took the veil of the nun. One suspects that her husband’s policy of curtailing the funds of the luxurious and innumerable monks alarmed her, and she was ready to believe that, as rumour maintained, the wild boar which led him into grave peril in 1059 was no ordinary animal. He resigned, and Æcatherina, changing her name to Helena, retired with her daughter Maria to a quiet mansion, where they practised monastic discipline and were esteemed so holy that Æcatherina was eventually buried in the cemetery of the monks of Studion.

With the next Empress, Eudocia, we return to the more familiar and more piquant type of Byzantine princess: the woman who unites with her subservience to the Church a skill in casuistry which protects her human inclinations from the harsher control of the Church’s ascetic standards. Eudocia Macrembolitissa, or Eudocia the daughter of Macrembolites, a distinguished noble of Constantinople, had some beauty and no little wit, as well as good birth and breeding. In the reign of Michael IV. and Zoe she had been wooed and won by a handsome and learned, if not very warlike, commander named Constantine Ducas, and had in the subsequent twenty years of changing rulers borne three sons and three daughters to her elderly husband. Constantine was at least ten years older than she, and had no higher ambition than to be regarded as a prince of letters and rhetoric. It must, therefore, have been an agreeable surprise to Eudocia to learn, in 1059, that the retiring Emperor had transferred his crown to her husband, and she was henceforth to be the mistress of the sacred palace.183 She was then, probably, in her later thirties. She was entitled Augusta, and the imperial dignity was conferred also on her six children, of whom the youngest was born after her coronation.

During the eight years of her husband’s reign Eudocia remained a silent witness of his futility and unpopularity. He retained his pedantry, and sought the laurels of learning and eloquence, while formidable enemies threatened the Empire on every side. In 1067 he perceived that his inglorious reign was about to end, and summoned Eudocia, the nobles and the patriarch to his couch. The nobles were commanded to swear to maintain the throne of Eudocia and her sons, and Eudocia was compelled to swear a portentous oath that she would not marry again. Possibly Constantine felt that he was not imposing a very heavy sacrifice on a woman who approached her fiftieth year, and it was plainly to the interest of his sons that she should not marry. Eudocia signed the written oath, and it was entrusted to the patriarch Xiphilin to keep in the great church.

The regency of Eudocia lasted about seven months, during which she emulated the conduct of Zoe and Theodora. She received ambassadors, heard trials and paid more direct and closer attention to the affairs of the Empire than her late husband had done. Two things, however, concerned her and illustrated the weakness of woman-rule at Constantinople. The Turks and other hostile neighbours were raiding the provinces with greater vigour, and the nobles were making this a pretext for intrigue to replace Eudocia with an Emperor. Before the year was out Eudocia decided to marry again and sought a means of evading the oath which the patriarch grimly guarded.

The story of her outwitting the patriarch is, as we find it in the later chronicles, in the finest vein of Byzantine melodrama. She took into her confidence one of the wiliest eunuchs of her Court, who assured her that it was quite easy to induce the patriarch to release184 her. This Xiphilin, the patriarch at the time, was himself as casuistic as he was religious. Originally a noble, he had voluntarily embraced the black robe of the monk, and had been withdrawn from the monastery to rule the Eastern Church. He had in Constantinople a brother named Bardas, whose gallantries and sybaritic ways were notorious. When the eunuch proposed the subject of marriage, Xiphilin sternly maintained that the oath was binding and that Eudocia must remain a widow, but when the astute eunuch regretted that such was his view, since it was his brother Bardas whom Eudocia wished to marry, Xiphilin reconsidered the matter. It is not for us to analyse his reasoning. It is enough that in a short time he declared to the assembled Senators that the oath was unjust and invalid, a mere wanton outrage on the part of a jealous man, and he handed the precious document back to Eudocia to destroy. His feelings may be imagined when, a few hours later, he heard that the Empress was married, not to his brother, but to Romanus Diogenes.

The contemporary writer Psellus gives a more sober version, but, although Psellus was one of Eudocia’s chief ministers at the time, there can be little doubt that his vanity and policy have somewhat tempered the veracity of his narrative. Eudocia, he says, came to him in tears to complain that the cares of Empire were an intolerable burden for a single woman’s shoulders, and she wished to marry. The story is, perhaps, not inconsistent with the story of her outwitting the patriarch. In any case, the second marriage of Eudocia had an element of romance.

In the state prison of Constantinople at the time was a handsome young noble and commander named Romanus Diogenes, who ran some risk of losing his head for high treason. Distinguished by birth and in person, and a man of great spirit, he reflected that the throne of the Eastern Empire had been reached by less able men than he, and cherished a daydream of wearing185 the purple. At the death of Constantine in 1067, when there was much discussion of the empty throne and the imperial widow, he imprudently confessed his ambition to those about him in the remote province of Thrace, which he governed; he was denounced in the capital; and he was brought in bonds to Constantinople and put on trial. He had then completed his thirtieth year: a tall, comely, broad-shouldered man, with the dark skin of a Cappadocian and very winning eyes. Constantinople looked with sympathy on the manly, but impetuous, young noble. He was connected by birth with the greatest families of the Asiatic provinces, and he pleaded that it was only his concern for the safety of the menaced Empire that had wrung from him words of dissatisfaction. His treason was, however, apparent, and he was found guilty and restored to jail.

Eudocia was probably present at the trial of Romanus, and noted the handsome form and flashing eye. She professed afterwards that the trial was unsatisfactory and must be revised, and the young commander found himself acquitted and free to return to his native province. The time was not yet ripe for the marriage project; in fact, one of the historians states that Romanus was already married, and went to join his wife and family in Cappadocia. About Christmas (1067), however, he received an order from Eudocia to return to Constantinople, and may or may not have been surprised to hear that she proposed to marry and crown him. His wife and family seem to have been deserted with great cheerfulness—unless we prefer to regard the statement in the chronicle as an error24—and Eudocia secretly prepared for the marriage. Senators were bribed to support the proposal, and, on 31st December, the patriarch was won by the stratagem which I have already described. That very night Romanus was introduced, fully armed, into186 the palace and secretly wedded to the Empress, and on the first day of the new year the young Emperor and his middle-aged Empress were ceremoniously presented to the people. For a moment it seemed as if the fierce Varangian guards were about to avenge what they regarded as a violation of the oath to the dead Constantine, but Eudocia prevailed on her elder sons to assure the guards that they had consented to the marriage, and the trouble was averted for the time.

It was, however, in face of considerable hostility that Eudocia and Romanus entered upon their task of governing the Empire. The clergy were naturally hostile, since their leader had been tricked into an ignominious concession; more distinguished nobles than Romanus envied his elevation; and courtiers who were attached to the fortunes of Eudocia’s elder sons regarded the new Emperor, and the possible issue of the new marriage, with sullen distrust. Michael Psellus, the historian who boasts that he guided Eudocia’s counsels in regard to the marriage, is transparently hostile to Romanus, and his historical work is largely responsible for the traditional prejudice against that brave and spirited, but injudicious and unfortunate, monarch. Psellus was not merely the chief student of philosophy in Constantinople, but an ambitious and successful courtier. His great repute in letters and philosophy gave him a commanding position in the Court of Eudocia, who had herself some literary ambition,25 and his secret and sinuous counsels must have deeply influenced the later course of the careers of Romanus and Eudocia. A philosopher-statesman was the great ideal which Plato, whose works he revived, had urged upon the Greeks, but the fortunes of Psellus remain so even throughout the various revolutions he outlived that one187 is tempted to compare him rather with Talleyrand than with Plato’s ideal.

Into this atmosphere of culture the robust Romanus was little fitted to enter, and some disdain must have been felt of his uncultivated ways. On the other hand, the brother of the late Constantine, John Ducas, who bore the dignity of Cæsar and jealously guarded the position of his nephews, was not less hostile to Romanus. The boys had received the purple before the death of their father, and the time was rapidly approaching when, with the assistance of their uncle and Psellus, they might begin to exercise their power. To this plan Romanus was a considerable obstacle. When we further learn that Romanus was gravely conscious of his duty to restore the strength and discipline of the army, and diverted funds from the entertainment of idle citizens to the pay and equipment of his troops, we realize that the life of the palace was preparing for one more of those tragic revolutions which punctuate the history of the Byzantine Empire.

From this Court atmosphere of pedantry and intrigue Romanus turned to the field of battle; he would strengthen his position by winning such laurels as his vigorous and warlike character seemed to promise him. Two months after his coronation a fresh invasion of the Turks was announced, and he led a large army out to meet them. After nearly a year’s absence he returned with some report of victories, but there had in the same year been heavy losses, and his success was not decisive enough to override the intrigues of his opponents. Already, we are told, he found Eudocia colder. Her attitude is attributed to his arrogance and boastfulness; we may suppose that it was just as much due to an instinctive irritation when her robust husband strode into the philosophic atmosphere of the palace with the smell of the camp clinging to him and the language of war on his lips. In two or three months he was off once more to the field, leaving Eudocia to her master of philosophy188 and her brother-in-law. Into their hands she placed the more virile cares of State, while she enlarged libraries, cultivated men of letters and fostered the higher ambition of making verses. Her eldest son, Michael, was associated with her in her cultural work.

When Romanus returned in the following winter, still without decisive success, he seems to have concluded that it would be better to remain in Constantinople, and the campaign of the third year was entrusted to his generals, but in the spring of 1071 he again prepared to take the field. Nothing but a crushing victory over the enemies of the Empire would enable him to silence his enemies in the Court and capital. Eudocia seems by this time to have wavered between admiration of her young and manly spouse and repugnance to his more robust standards of life. She was now certainly over fifty, and had never been particularly sensuous, but we cannot doubt that she had married Romanus for love and that that love was not yet extinct. As he set out from port for his last crossing to Asia a singular dark-plumaged pigeon circled his royal galley. He directed that it should be caught and sent to the Empress; and it was said in later years that Eudocia nervously recognized in the rare bird an omen of the evil fortune that was about to befall her husband.

And in the course of the summer stragglers made their way hastily to Constantinople with the news that Romanus had been heavily defeated and his large army shattered. The Emperor himself had been slain, some said, but at length there came men who had seen him captured and borne away, a prisoner, by the Turks. The hour of the malcontents had come, and a council was summoned to discuss the situation. It was at once decided that no effort would be made to save Romanus—some of the authorities declare that it was the treachery of the Cæsar’s son, acting on the instructions of his father, which led to the reverse—but the eldest son, Michael, should be appointed ruling Emperor, together with his mother.

189 That Eudocia at once surrendered her husband becomes quite clear from the subsequent course of events. The new administration had hardly settled to its work when Eudocia received a joyful letter from her husband announcing that he was free, and on his way to Constantinople. How the Turk had entirely falsified his repute for barbarity, treated Romanus as a brother king in misfortune, and eventually released him on promise of a ransom, is a familiar and attractive picture in the history of the time. Romanus was hastening to the arms of his beloved wife. Eudocia is described by contemporary writers as “distracted” and eager to consult those about her as to her conduct. Of wifely feeling she did not exhibit one sincere particle, and, however we may remind ourselves of the inevitable coldness of a woman in her sixth decade of life, her conduct is somewhat repellent. Had she known that the Cæsar was bent on bringing her to a common ruin with her husband, she might at least have purchased some loyalty to him, in the usual Byzantine fashion; but she was either ignorant or powerless, and she accepted the counsel that Romanus should be disowned and repelled by force from his Empire.

John Ducas, however, concluded that the opportunity was convenient for the removal of both Emperor and Empress. A decree was issued to the provinces to arrest the advance of Romanus, and the guards were marshalled. At this date the mercenary troops in charge of the palace were the famous and formidable Varangian guards, in whom modern authorities recognize the blue-eyed giants of distant Scandinavia and even of Britain. Romanus had favoured the native troops of the Empire rather than these foreign mercenaries, and they at once accepted the command of the Cæsar. One half of them went to the apartments of Michael, and declared him sole Emperor of the Romans; the other body went in search of Eudocia, with orders to transfer her to a monastery.

190 Eudocia at once concluded that the end of her rule had come when she heard the jubilant clash of axe on shield, the deep guttural voices, raised in song, of the northern soldiers, and their heavy tread across the gardens and terraces. Fearing for her life, she hid herself in some sort of hut in the grounds of her palace, but the door was presently flung open and she looked on the fierce hairy faces and shining weapons of the Varangians. She was prostrate with terror when the Cæsar arrived, to give her the comparative consolation that her life would be spared, but her empire was over. From the palace, spoiled of all the ensigns of royalty, we follow her along the short and painful route that we have seen so many proud rulers of the sacred palace take. At the Bucoleon quays a swift galley waited to take her to the Asiatic shore, where she was lodged in a monastery which she herself had founded. A further message soon came, ordering her to take the black veil, and the frail and unfortunate woman bade farewell to all the glories of imperial life. It was only four years since she had been left in control of the Empire by her first husband.

Shortly afterwards she was summoned to bury Romanus, and with him the last flickering hope of a return to power. He had collected an army and resolved to fight for his throne, and the troops of Ducas at length pinned him in a town of Cilicia. In order to end the civil war John now sent an assurance that the life of Romanus would be spared if he would resign his claim and enter a monastery; nay, three archbishops were sent to give him a solemn testimony that John had sworn and would fulfil his oath. Frail as the most formidable oaths had become in Eastern Christendom, Romanus opened the gates and yielded to the sons of the Cæsar. The rest of the story is a chapter of nauseous horror, and concerns us, fortunately, only in outline. Romanus was conveyed across Asia Minor, in the robe of a monk, with studied insult. Most of the chroniclers affirm that191 poison was administered to him, but that his powerful constitution prevented it from doing more than add to his misery. At length his eyes were cut out with more than ordinary brutality, the roughest and most elementary attention to his bleeding sockets was refused, and he was borne once more on a mule, dying by inches in the most ghastly conceivable fashion, across Asia Minor. He reached the island of Prote in time to die on the soil that was already watered by so many imperial tears, and the chroniclers add that Eudocia gave a splendid funeral to the remains of the man whom she had transferred from the jail to the palace, less than four years before, in the full pride of a magnificent manhood.

I have said that with the remains of Romanus she buried her last hope of returning to power, yet some seven years afterwards a strange message reached her in her cloister, recalling the memory, if not the hope, of imperial power. Her son Michael proved an ineffective ruler. The tradition of culture which had lingered in the palace since the days of Psellus absorbed all his energy, and he could not be diverted from the dialogues of Plato or the iridescent dreams of Plotinus by mere conspiracies against his throne or invasions of his Empire. Indeed, it was with difficulty, sometimes, that they could drag him to table or persuade him to refrain from spending the night over his books. The irony of the situation was that, while the Greek writings over which he lingered urged that a profound study of philosophy was the fittest education of monarchs, Michael remained as helpless and heedless as a boy, precisely on account of his studies. Fortunately, he had the casual inspiration to call to the palace a wily eunuch, named Nicephorus, who become the virtual ruler. Nicephoritzes—as the people, using the diminutive form of his name, called the pale and shrunken little eunuch—soon displaced the Cæsar John, and, as was the invariable custom of his kind, enriched himself at the expense of the impoverished and decaying provinces.

192 Under Nicephoritzes Eudocia had no chance of a return to power. He had endeavoured to persuade her first husband, the Emperor Constantine, that she was unfaithful to him, and had been driven from office during her regency. But the Empress’s quarters in the palace were not vacant; a new type of Empress was added to the long and varied gallery. Shortly before his accession to the supreme throne Michael had married a princess of one of the tribes that had settled in Asia Minor. The father of the Empress Maria is conflictingly described as a king of the Iberians and the Alans, and is said to have been a ruler of great fame and power; but he is not named, and it seems that he was not powerful enough to avert or temper the tragedy of his daughter’s career. Her dowry had been her beauty. I have complained at times of the lamentable indifference of the male historians of Constantinople to the physical features of the Empresses, and the lack of portraits which might bring the living figure with any fulness or accuracy before the imagination. We now, however, approach a period, the history of which has been written for us by a woman, the famous Anna Comnena, and her pen happily wanders at times back to the age of Eudocia, of which her husband, Nicephorus Bryennius, was the chief historian.

Unhappily, the art of which Anna Comnena was so patently proud did not include skill in portraiture. Maria was the most beautiful woman of her time, and, although her interests become opposed to those of Anna and her family, and the learned princess was capable of malignant hatred, Anna Comnena rises to the height of superlative when her pen delineates the figure of Maria. Her grace of form and beauty of face were beyond the artist’s power to convey; though one must add that Anna not infrequently uses that formula, in order to enhance the artistic wonder of her own descriptions. Maria, she says, was tall and graceful as a cypress; her body was white as snow, save for the roses193 that bloomed in her cheeks, and the luminous blue eyes which shone beneath the perfect and lofty arch of her auburn eyebrows. To this vague poetical description we may add at once that the beautiful young princess was not wholly devoid of the spirit of her tribe, and was prepared for romantic adventure in support of the imperial dignity.

The seven years of Michael’s reign do not interest us. The Emperor lived in the remote solitude of his exalted studies; Maria enjoyed the superb luxury of her position, and brought a prince into the world for the greater security of her throne; Eudocia languished in the royal monastery of the Virgin across the straits. Usurpers rose and fell, and the defrauded people spoke with bitterness of the young pedant who let his ministers rob them while he studied the divine maxims of Plato. Another princess, daughter of Robert of Lombardy, was introduced from the West, but she was, like Maria’s son, to whom she was betrothed, a child of tender years, looking with strange blue eyes on the vast palaces she would one day govern—they said—and the boy who shyly shrank from her companionship.

At last, in 1078, a more fortunate rebel advanced on Constantinople, the clergy and nobles were bribed to espouse his cause, and Michael fled to the Blachernæ palace in the suburbs. Maria accompanied him, and what we know of her character emboldens us to fancy her urging the distracted scholar to draw a sword on behalf of his throne. His friends, however, found it impossible to move him, and, yielding to the usurper, he was conducted on an ass to the monastery at Studion, where he might prosecute his studies with even greater leisure. The new Emperor had so genial a disdain for him that he made him titular Bishop of Ephesus, and allowed him to return and live in the capital.

Maria, in accordance with custom, entered the suburban monastery at Petrion. She did not, however, take the vows of the religious life, and it was not long before194 the interesting news came that the new Emperor designed to marry her. Nicephorus Botaneiates was an elderly voluptuary, who had seized the throne only because so little energy was needed for the task. For the administration of public business he had two slaves of his own household, of Slavonian extraction, who at once put an end to the life of Nicephoritzes and diverted the stream of gold to their own pockets. For their master the pleasures of the table and the couch sufficed. He had brought to the throne an obscure Empress named Berdena, but she died shortly afterwards, and the aged Sybarite consulted his ministers. To their cold and impartial judgment it seemed that political considerations must rule the choice and they were divided between the claims of Maria and those of Eudocia. It is true that Nicephorus had been twice married, that Eudocia was a nun, and that Maria was not yet a widow; but such difficulties were never beyond the casuistic resources of the Constantinopolitan clergy. The Emperor must marry, since the sacred ritual of the Court demanded the presence of an Empress.

The politicians favoured the suit of Eudocia, and she was actually informed that Nicephorus wished to marry her, and expressed her cordial willingness to sacrifice her monastic estate in view of such august considerations. Nicephorus, however, was, as I said, a Sybarite, and even advanced age did not blur his experienced eye to the charms of Maria. We may, therefore, suppose that Nicephorus was neither surprised nor pained when a certain very holy monk appeared at the monastery of the Virgin and sternly forbade Eudocia to quit her black robe. It may be that the monk was one of the chaplains of the monastery; it is at least clear that his zeal did not take him to the monastery at Petrion, where Maria resided. The beautiful young Empress was recalled from her prayers and fasts and conducted to the side of the Emperor in the palace chapel. The patriarch, who seems to have had some scruples, was not summoned195 to perform the ceremony, and Nicephorus noticed with irritation that the priest who was called hesitated to come to the sanctuary; Nicephorus had no dispensation for a third marriage, and Maria’s husband still lived. A courtier, however, had foreseen the difficulty and had a more accommodating priest at hand. The irregular knot was tied, or regarded as tied, and Maria returned to enjoy, with her son, the pleasures of the Emperor’s luxurious Court.

It is, perhaps, no alleviation of the conduct of Maria, in purchasing her crown by an invalid marriage to an elderly sensualist, to say that—the chroniclers assure us—quite a number of noble ladies at Constantinople were eager to be chosen. Eudocia, her youngest daughter, Zoe, and many other ladies had been pressed upon the notice of Nicephorus. It is merely one more indication of the inferiority of character, both in men and women, in the Byzantine Empire. But Maria was not destined to enjoy long the throne which she had purchased. Contemptible as the reign of Michael had been, it was succeeded by one far more contemptible, and sullen murmurs filled the palace and the city. Men told each other how the aged Emperor, who ought to be thinking of eternity, changed his splendid robes ten times a day, anointed his jaded frame with the most costly unguents, and sat down, day after day, to the most superb banquets that the Empire could afford; while the two barbaric slaves whom he had made his chief ministers ground the despairing provinces and disgusted the nobles. Within a year or two of Maria’s return to power, the customary, inevitable revolt arose, and she was driven back to her monastery.

This revolution, however, introduces us to the strong women of the Comnenian house and must commence a fresh chapter. Of Eudocia we hear no more. If we accept the statement of one of the chroniclers, that she had married in the reign of Michael IV. (1034–1041), she must now have reached her seventh decade of life, and196 would probably not long survive her last disappointment. Her readiness, in her later sixties, and after seven years of monastic life, to accept the embraces of a roué like Nicephorus, in return for the crown, is a sufficient measure of her character; her violation of her oath to her first husband, and her desertion of her second husband, point to the same feebly vicious and unattractive type of personality. Through the favour of Nicephorus she was permitted to leave the suburban monastery, and spend her last years in considerable comfort in the city.

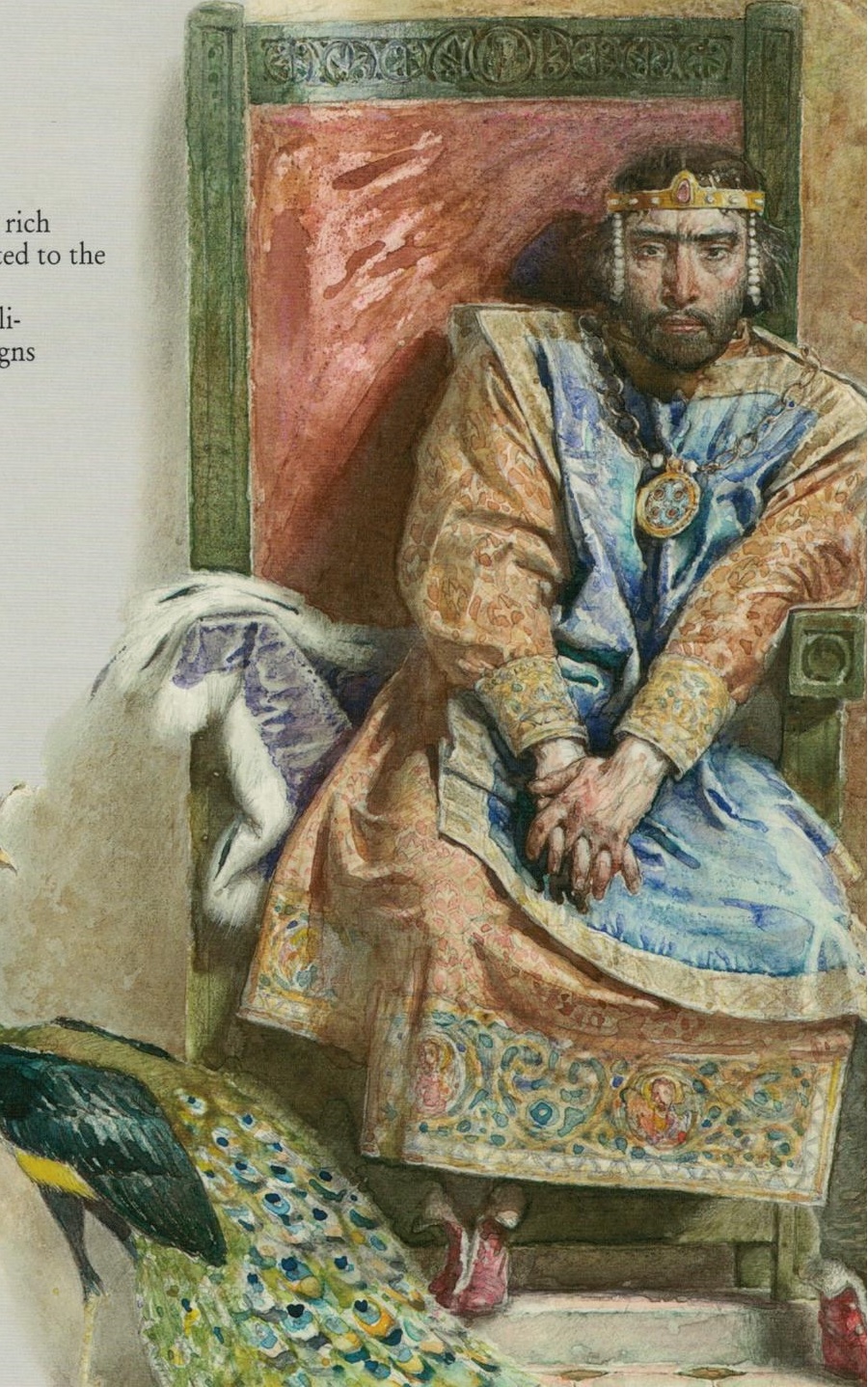

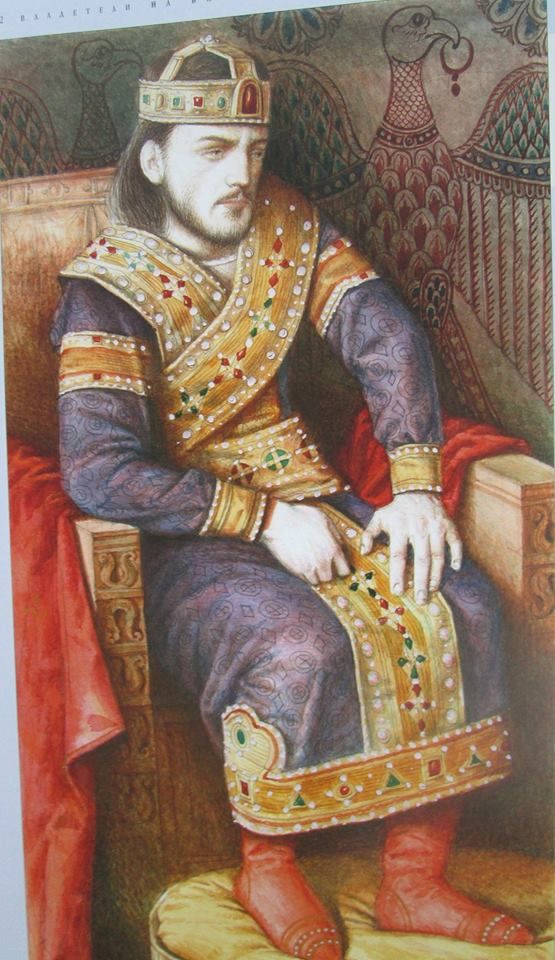

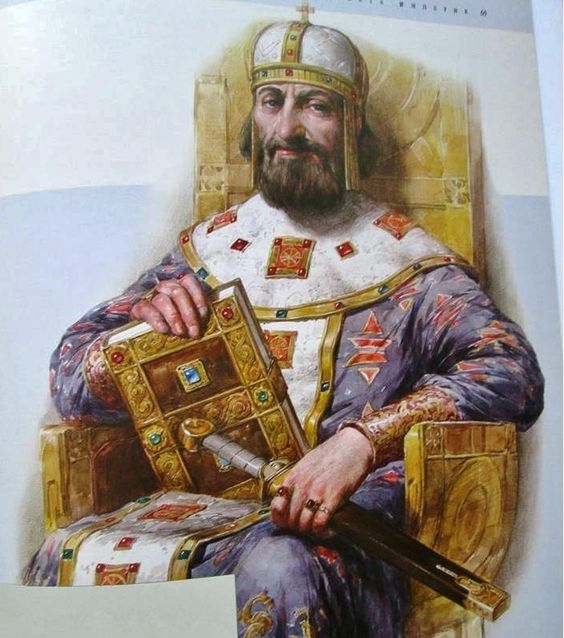

Emperor John I Tzimiskes, the murderer of his uncle Nikephorus II Phocas in his bed in the Boukoleon Palace. John married his uncle's wife, who was his co-conspirator in the assassination.

Emperor John I Tzimiskes, the murderer of his uncle Nikephorus II Phocas in his bed in the Boukoleon Palace. John married his uncle's wife, who was his co-conspirator in the assassination.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints