1453 - Byzantium in the Last Days of Constantinople

The Destruction of the Greek Empire and the Story of the Capture of Constantinople by the Turks

Author: Edwin Pears

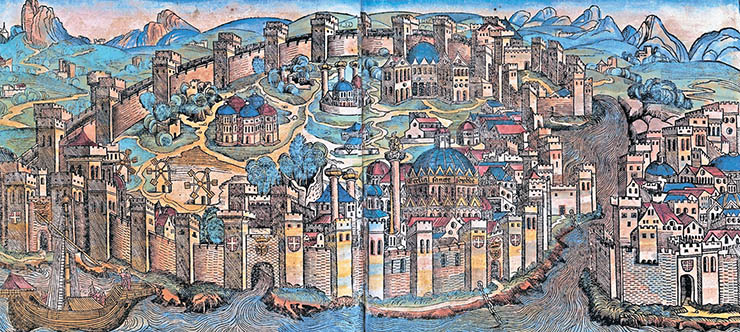

It is impossible to arrive at an accurate estimate of the population of the city on the accession of the last Constantine. La Brocquière, in 1433, describes Constantinople as formed of separate parts and containing open spaces of a greater extent than those built on. This is one of many intimations that the population had largely decreased. Some of the nobles as well as the common people had left the city as soon as they saw that a siege was probable. To make an estimate we must anticipate our narrative of the siege. Critobulus makes Mahomet appeal to the knowledge of his hearers in proposing to besiege the city when he states that the greater number of the inhabitants have abandoned it; that it is now only a city in name and contains tilled lands, trees, vineyards, and enclosures as well as ruined and destroyed houses, as they have all seen for themselves. As his hearers could see as well as he whether this statement was correct, there can be little doubt of its accuracy. He further declared that there were few men in the city and that these for the most part were without arms and unused to fighting, and that he had learned from deserters that there were only two or three men to defend each tower, so that each man had to guard three or four crenellations. Tetaldi states that there were in the city from twenty-five thousand to thirty thousand men and six to seven thousand combatants and not more. The actual census taken at the request of the emperor and recorded by Phrantzes gives under five thousand fighting men, exclusive of foreigners. Assuming the statement of the French soldier and eye-witness Tetaldi to be substantially correct, there would apparently be something like eighteen thousand monks and old men incapable of bearing arms. The only other indications which assist in forming an estimate of the population are furnished by the number of prisoners. These are probably exaggerated. Archbishop Leonard estimates them at above sixty thousand. Critobulus gives the number of slaves of all kinds, men, women, and children, as fifty thousand citizens and five hundred soldiers, estimating that during the siege and capture four thousand were killed. Probably all captives are included as having been reduced to slavery. The complete desolation of the city and the strenuous efforts made by the sultan to repeople it after the capture raise a strong presumption in favour of the existence of a comparatively small population at the time of the siege. Gibbon judged that ‘in her last decay Constantinople was still peopled with more than a hundred thousand inhabitants,’ forming his estimate mainly upon the declaration of the archbishop as to prisoners. I am myself disposed to think that this number is rather over- than under-estimated. Taking the prisoners to be fifty thousand, and allowing for the escape of ten thousand persons and another ten thousand for old men and women who were not worth reducing to slavery, probably eighty thousand would be about right.

Within the narrow limits of what had been possible, the citizens over whom the new emperor was called to rule had done their duty to the city itself. They had kept fourteen miles of walls the most formidable in Europe in good repair and they had preserved the wonderful aqueducts, the cisterns, the great baths and churches.

Within the narrow limits of what had been possible, the citizens over whom the new emperor was called to rule had done their duty to the city itself. They had kept fourteen miles of walls the most formidable in Europe in good repair and they had preserved the wonderful aqueducts, the cisterns, the great baths and churches.

Its commerce.

Commerce still continued to be the principal support of the inhabitants. This was now largely shared by the Genoese in Galata and by the Venetians who occupied a quarter in Constantinople itself. The familiarity of the Italian colonists with Western lands and their superiority in shipping, in which indeed at this time they led the world, enabled them to achieve a success in what was then long-voyage travelling which was denied to the Greeks; but the latter collected merchandise from the Black Sea ports and from the Azof which was either sold to the Frank merchants in Constantinople or transhipped on board their vessels.

Emperor and nobles.

Emperor and nobles.

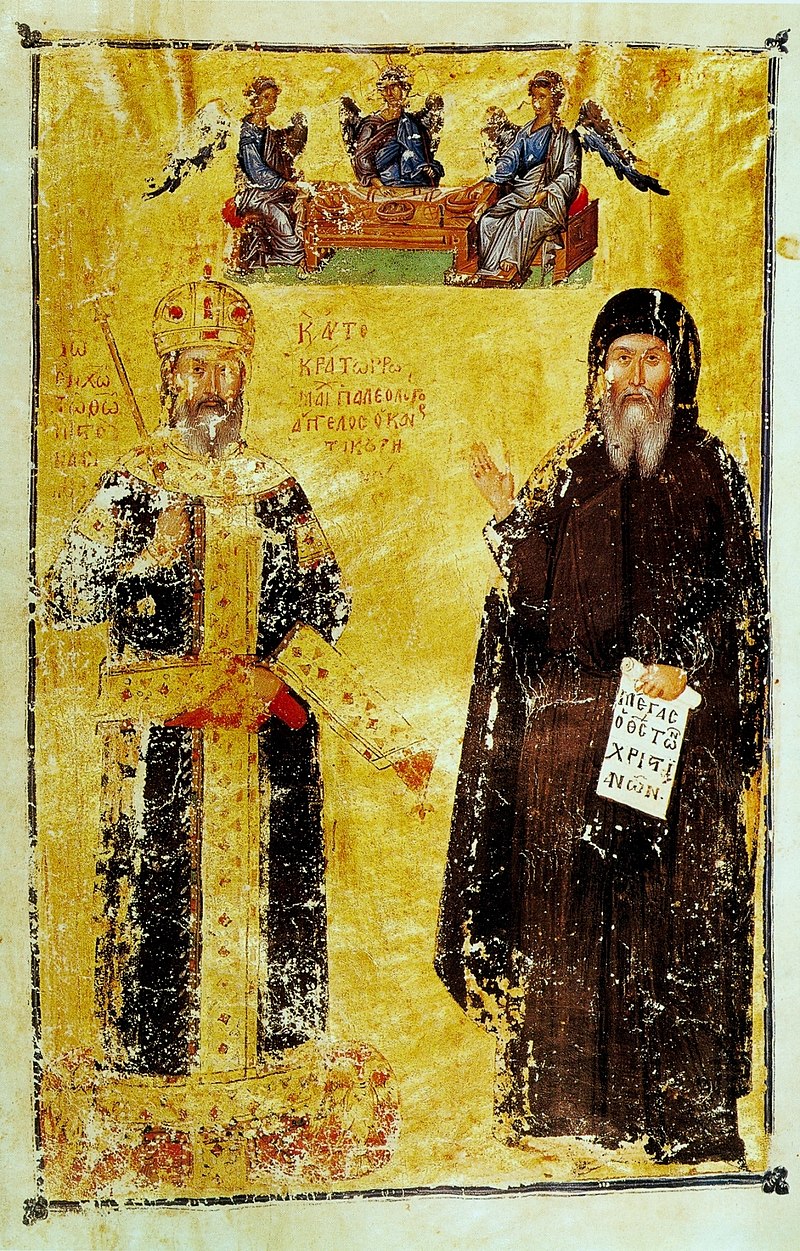

It is difficult to realise what were the relations between the government and the governed during the two centuries before the last catastrophe. The empire was the continuator of the autocratic—or rather the aristocratic—form of government which had been derived from the elder Rome. Emperor and nobles governed the country. The nobles formed the senate. Like our own Privy Council, it met rarely and had ill-defined functions, but upon occasions of195 emergency it had to be consulted. Its co-operation gave to any measures edicted by the emperor an important sanction. When the decision of the senate was acquiesced in by or coincided with that of the Patriarch and his ecclesiastical council, the emperor may be said to have possessed all the approval that could be derived from public opinion.

Though the senate met rarely, its support was never altogether dispensed with. The emperors did not claim to reign by divine right, nor was any such pretext put forward on their behalf. The succession passed in the usual manner and the emperor reigned with almost autocratic powers so long as the nobles and the patriarch and ecclesiastics were content. In the period with which we are concerned the nobles sometimes preferred to associate a younger man with the occupant of the throne. Such association was usually, though not always, in accordance with the desire of the reigning emperor, and had the conspicuous advantage of allowing the elder to train his younger associate in statecraft. In some cases, as in those of young Andronicus and of John during the reign of his father, Manuel, it was imposed upon the emperor in order to bring about a change of policy.

No form of popular representation existed. The mass of the people had nothing to do with the laws except to obey them. So long as their lives and their property were protected and the laws fairly administered they were content.

Administration of law.

So far as can be judged from the silence as well as from the writings of the Byzantine writers, there was little fault to find with the administration of law. When cases of the miscarriage of justice are mentioned they are generally brought forward to show the scandal they had produced or in some other connection which suggests that such cases were exceptional. It was not only that the keen subtlety of a long succession of Greek-speaking lawyers had preserved the traditions of their great ancestors of the time of Justinian and had guarded law in admirable forms, but the still better traditions of an honest administration of law had continued, and this with the result—simple as it may196 appear to Western readers; strange as it would have sounded to a Turkish subject at any time since the capture of Constantinople—that people believed that the decisions of the law courts were fairly given.

Interest in religious questions.

Interest in religious questions.

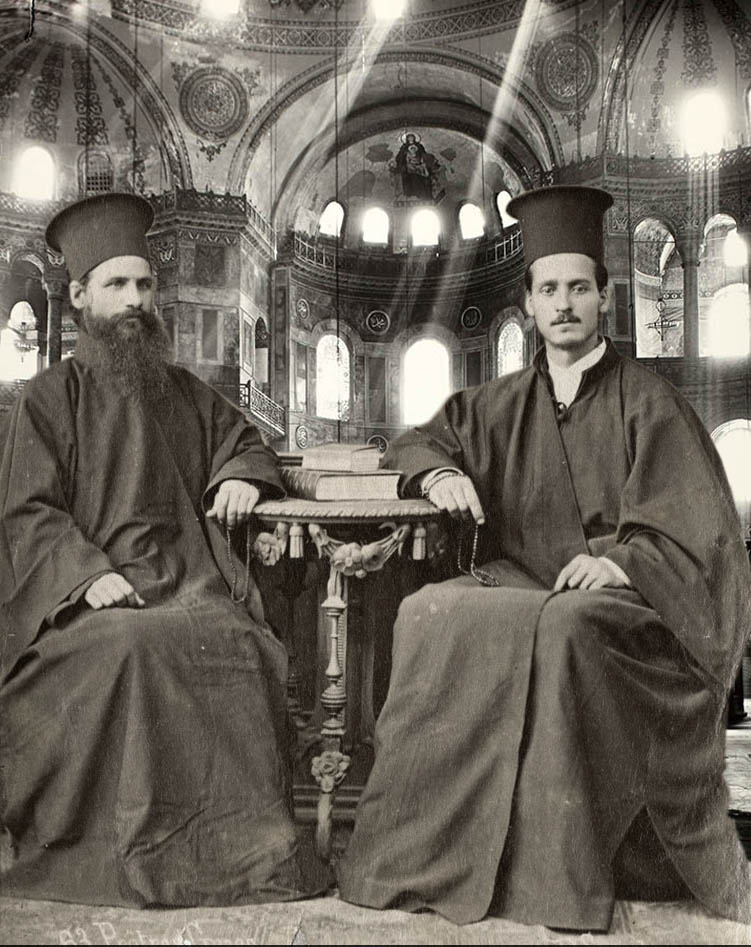

The inhabitants of the capital retained until the last days of its history as a Christian city their intense interest in religious questions. It is of less importance to qualify such interest as superstitious or fanatical than to try to understand it. That theological questions possessed a dominating influence over the people of Constantinople is one of the facts of history, and represents an important element in the education of the modern Western world.

An able modern writer says with justice that ‘religious sentiment was down to the fall of the empire as deep as it was powerful. It took the place of everything else. Probably the exclusion of the great bulk of the inhabitants from all participation in government and the consequent want of general interest in political questions or those regarding social legislation helped to concentrate attention upon those relating to religion. The Greek intellect—and, though there were large sections of the population which were not Greek, the Greek element as well as the Greek language gave its tone to all the rest—was essentially active and philosophical. The investigation of theological questions was not conducted lightly. The same spirit which made scholars of Constantinople espouse the study of Plato as they had done for two centuries before 1453—a study which caused Pletho, on his visit with John at the Council of Florence, to be regarded as an authority to be eagerly sought after by those awakening to the new learning in Italy—had been applied to many questions of philosophy and theology. The examination of such questions was more speculative, thorough, and scientific than in the West.

An able modern writer says with justice that ‘religious sentiment was down to the fall of the empire as deep as it was powerful. It took the place of everything else. Probably the exclusion of the great bulk of the inhabitants from all participation in government and the consequent want of general interest in political questions or those regarding social legislation helped to concentrate attention upon those relating to religion. The Greek intellect—and, though there were large sections of the population which were not Greek, the Greek element as well as the Greek language gave its tone to all the rest—was essentially active and philosophical. The investigation of theological questions was not conducted lightly. The same spirit which made scholars of Constantinople espouse the study of Plato as they had done for two centuries before 1453—a study which caused Pletho, on his visit with John at the Council of Florence, to be regarded as an authority to be eagerly sought after by those awakening to the new learning in Italy—had been applied to many questions of philosophy and theology. The examination of such questions was more speculative, thorough, and scientific than in the West.

While it is true that Constantinople had for centuries produced few ideas and little of original value in literature, it had rendered great service to humanity by preserving the Greek classics. Its methods of thought, its civilisation as well as its literature, were on the model of classical antiquity, but these were all modified by Christianity. Part of the mission of the empire had been to save during upwards of a thousand years, amid the irruptions of Goths, Huns and Vandals, Persians and Arabs, Slavs and Turks, the traditions and the literary works of Greece. It had done this part of its work well. Amid the obscurity of the Middle Ages in the West, Constantinople had always possessed writers who threw light on the history of the empire in the East. No European people, remarks a recent writer, possesses an historical literature as rich as do the Greeks. From Herodotus to Chalcondylas the chain is not broken. The Greek historians of the period with which the present work is concerned, Pachymer, Cantacuzenus, Gregoras, Ducas, Critobulus, and Phrantzes are in literary merit far superior to the contemporary chroniclers of the West. Though their works are written in a style which aims at reproducing classical Greek and imitating classical models, they were not intended merely for Churchmen. Nor was Constantinople rich only in historians.

While it is true that Constantinople had for centuries produced few ideas and little of original value in literature, it had rendered great service to humanity by preserving the Greek classics. Its methods of thought, its civilisation as well as its literature, were on the model of classical antiquity, but these were all modified by Christianity. Part of the mission of the empire had been to save during upwards of a thousand years, amid the irruptions of Goths, Huns and Vandals, Persians and Arabs, Slavs and Turks, the traditions and the literary works of Greece. It had done this part of its work well. Amid the obscurity of the Middle Ages in the West, Constantinople had always possessed writers who threw light on the history of the empire in the East. No European people, remarks a recent writer, possesses an historical literature as rich as do the Greeks. From Herodotus to Chalcondylas the chain is not broken. The Greek historians of the period with which the present work is concerned, Pachymer, Cantacuzenus, Gregoras, Ducas, Critobulus, and Phrantzes are in literary merit far superior to the contemporary chroniclers of the West. Though their works are written in a style which aims at reproducing classical Greek and imitating classical models, they were not intended merely for Churchmen. Nor was Constantinople rich only in historians.

Civilisation not modern.

Though intellectual life was never wanting in the city, many of whose people possessed the quick, ingenious, and piercing intellect of the Greek race, the reader of the later historians feels that the civilisation amid which they lived was not that of modern times. It is difficult to realise what it was like. It has often been compared with that of Russia, and writers of reputation have spoken of that empire as preserving the succession of the political and religious systems of Byzantium as well as of its mission to the non-civilised nations of Asia. Allowing for the difference between the Greek and the Slav intellect, the analogy in a general sense holds fairly good, and is especially noticeable in two points, the religious spirit of both peoples and their contented exclusion from all active participation in the government.

Though intellectual life was never wanting in the city, many of whose people possessed the quick, ingenious, and piercing intellect of the Greek race, the reader of the later historians feels that the civilisation amid which they lived was not that of modern times. It is difficult to realise what it was like. It has often been compared with that of Russia, and writers of reputation have spoken of that empire as preserving the succession of the political and religious systems of Byzantium as well as of its mission to the non-civilised nations of Asia. Allowing for the difference between the Greek and the Slav intellect, the analogy in a general sense holds fairly good, and is especially noticeable in two points, the religious spirit of both peoples and their contented exclusion from all active participation in the government.

It is, however, difficult to determine how far the conditions of existence in the first half of the fifteenth century among the citizens of the capital resembled those found in Russia. The difficulty arises, not merely from distance of time, but from the fact that in the empire manners, usages, the conception of life, and the influence of religion were neither Western nor modern. The people were governed much as Russia is governed now: but there were important differences due to race, tradition, and environment. Nevertheless, the condition of the empire reminds one of the Russia of fifty years ago. There were the same great distances between the capital and the provinces and the same difficulty of communication. News travelled slowly; public opinion hardly existed. There were in the country a mass of ignorant peasants tilling the ground and caring little for anything else, peasants who were in a condition of serfdom, thinking of the emperor as a demi-god and rendering unquestioning obedience to his representatives; thinking of the Church as a divine institution entrusted with miraculous powers to confer a life after death, but far too ignorant to trouble themselves about heresies or dogmas. Among these peasants probably only the priests and monks were able to read, although among a people naturally intelligent this would not necessarily imply a want of interest in what was going on around them. The analogy to Russia must not be pushed too far. Religion and language, a common form of Christianity and the traditional duty of submission to the rule of Constantinople were the bonds which held the empire together, but the Greek tendency to individualism and the political development of the empire which destroyed the belief that allegiance was necessarily due to the ruler in the capital had been for two centuries a disintegrating element which prevented the growth of the apathy on political and social questions, and the deadly contentment which has been a characteristic of the great Slavic race.

It is, however, difficult to determine how far the conditions of existence in the first half of the fifteenth century among the citizens of the capital resembled those found in Russia. The difficulty arises, not merely from distance of time, but from the fact that in the empire manners, usages, the conception of life, and the influence of religion were neither Western nor modern. The people were governed much as Russia is governed now: but there were important differences due to race, tradition, and environment. Nevertheless, the condition of the empire reminds one of the Russia of fifty years ago. There were the same great distances between the capital and the provinces and the same difficulty of communication. News travelled slowly; public opinion hardly existed. There were in the country a mass of ignorant peasants tilling the ground and caring little for anything else, peasants who were in a condition of serfdom, thinking of the emperor as a demi-god and rendering unquestioning obedience to his representatives; thinking of the Church as a divine institution entrusted with miraculous powers to confer a life after death, but far too ignorant to trouble themselves about heresies or dogmas. Among these peasants probably only the priests and monks were able to read, although among a people naturally intelligent this would not necessarily imply a want of interest in what was going on around them. The analogy to Russia must not be pushed too far. Religion and language, a common form of Christianity and the traditional duty of submission to the rule of Constantinople were the bonds which held the empire together, but the Greek tendency to individualism and the political development of the empire which destroyed the belief that allegiance was necessarily due to the ruler in the capital had been for two centuries a disintegrating element which prevented the growth of the apathy on political and social questions, and the deadly contentment which has been a characteristic of the great Slavic race.

In the cities there was intellectual life: Salonica, Nicaea, Smyrna, and other centres of population had in times past vied with the capital in general culture and still retained something of their attachment to it. To the last hour of the empire there was, as we have seen, general and absorbing interest in the question of the Union of the Churches. But interest in other questions which had once kept religious thought from stagnation had largely died out. The more pressing questions of life interested the citizens. Moreover, the people believed that all questions of Christian belief had been settled. The Creed was final and had no more need of revision than the style of the Parthenon. The practices adopted from Paganism had become so generally accepted as to pass without dispute. Iconoclasts and Paulicians can hardly be said to have left any representatives. A Pagan Christianity with a Pantheism accepting holy springs, miraculous pictures, miracle-working relics, had become the accepted form of faith, a form which we of the twentieth century find it as difficult to understand as the earlier belief which had regarded the emperor as divinity.

In the cities there was intellectual life: Salonica, Nicaea, Smyrna, and other centres of population had in times past vied with the capital in general culture and still retained something of their attachment to it. To the last hour of the empire there was, as we have seen, general and absorbing interest in the question of the Union of the Churches. But interest in other questions which had once kept religious thought from stagnation had largely died out. The more pressing questions of life interested the citizens. Moreover, the people believed that all questions of Christian belief had been settled. The Creed was final and had no more need of revision than the style of the Parthenon. The practices adopted from Paganism had become so generally accepted as to pass without dispute. Iconoclasts and Paulicians can hardly be said to have left any representatives. A Pagan Christianity with a Pantheism accepting holy springs, miraculous pictures, miracle-working relics, had become the accepted form of faith, a form which we of the twentieth century find it as difficult to understand as the earlier belief which had regarded the emperor as divinity.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints