The Kahn Byzantine Madonna is the finest surviving Byzantine icon. It dates from the 12th century and was painted in a workshop in Constantinople - the capital of the Byzantine Empire. It is large - over 51 inches tall and was discovered in a state of fine preservation. The only damage was two splits in the wood, one above the head of the Virgin and the other on the right which passes through the medallion of the Archangel. The Mellon Madonna came to the National Gallery in 1937 and the Kahn Madonna came 12 years later in 1949.

The Kahn Byzantine Madonna is the finest surviving Byzantine icon. It dates from the 12th century and was painted in a workshop in Constantinople - the capital of the Byzantine Empire. It is large - over 51 inches tall and was discovered in a state of fine preservation. The only damage was two splits in the wood, one above the head of the Virgin and the other on the right which passes through the medallion of the Archangel. The Mellon Madonna came to the National Gallery in 1937 and the Kahn Madonna came 12 years later in 1949.

The Theotokos - as she is called in the Orthodox church, meaning God-Bearer - wears a blue maphorion on top of a dark blue dress. Both are painted in two tones of Ulramarine blue, which is made of ground Lapis Lazuli from mines high up in the mountains of Afghanistan. Around her head she wears a bright blue silk cap painted in ultramarine mixed with lead white. Her slippers are painted in vermilion. Christ wears a robe painted in red vermilion. It is decorated with two blue stripes. Around his waist he wears a belt in the same color. Christ carries a scroll in one had and blesses his mother with the other. The throne and footstool is painted in yellow oxide. The Theotokos sits on vermilion red silk cushion.

All the shapes and forms of the robes of both the Theotokos and Christ are defined by the brilliant application of chrysography and the use of gold highlights. The artist who applied them did it flawlessly. Perhaps this is the finest example of this technique to survive.

It is surprising how limited the Byzantine color palate was. Earth colors like ochres where inexpensive and could be found all around Constantinople and nearby regions. Lead white was easy to produce and inexpensive. Vermilion is a dense, opaque pigment with a clear, brilliant hue. The pigment was made in Byzantium by grinding a powder of cinnabar which was mercury sulfide, it is toxic. Vermilion is not one specific hue; mercuric sulfides make a range of warm hues, from bright orange-red to a duller reddish-purple. Differences in hue are caused by the size of the ground particles of pigment. Larger crystals produce duller and less-orange hue. It was a by-product of the mining of mercury. The Byzantines used mercury to gild silver.

Ultramarine was made by crushing and grinding the semi-precious stone Lapis Lazuli which was imported from mines in Afganistan. These mines were very ancient and had been mined in pre-history. The pigment came in different levels of blueness, with pure blue being the most valuable. Less expensive Lapis pigment was more gray due to white particles being ground into it from inferior quality stone. The supply of Lapis-ultramarine was often interrupted. It traveled from the east by caravan and was then taken by sea via the port of Trebizond to Constantinople. In Constantinople Lapis-Ultramarine was sold by the weight through the same shops that sold rare perfumes like amber. Other pigments were sold through artists shops where you could also buy brushes and grinding materials. Panel paintings like icons required less pigment than frescoes. Lapis was usually too expensive to be used as backgrounds in frescos and was often only used for the robes of the Theotokos or Christ. Backgrounds were painted black nd then cheaper blue glaze washes were applied in colors like Azurite.

I used to import Lapis powder from Afghanistan at great expense for my own icons. It was too difficult to prepare and I wasted hundred of dollars of it. The grains of the powder were too large and had too many impurities, it came out too gray and grainy. The egg as a binder would not mix properly. It is better to buy it from an established supplier that guarantees purity and size of the grains.

The Virgin's blue drapery have been drawn with black lines outlining the folds. The icon painting technique of building up modelling by fine lines getting lighter and lighter does not work with blue ultramarine. Highlights rob the blue of its intensity. The use of chrysography in gold highlights is an excellent - and dramatic - choice to add modeling to the folds. It works very well in low-light or candlelight.

The icon appeared on the art market around 1915 in Spain, along with the so-called Mellon Madonna, which is also in the National Gallery. It was claimed that the were found in a church, or convent, in Calahorra, a province of La Rioja, Spain. One theory says that both icons were brought to Spain by Anna of Hohenstaufen (1230 – April 1307), who was born Constance, and was an Empress of Nicaea. She was a daughter of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor and Bianca Lancia. She married Nicaean Emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes when she was 14 in 1244. Her husband lost power and she was given magnificent presents and allowed to leave for the Kingdom of Sicily in 1263. Constance was then forced to flee Sicily for Aragon, where her niece, Manfred's daughter Constance, was the consort of Crown Prince Peter. She remained for some time at the court of King James I of Aragon, but eventually retired as a nun to a monastery in Valencia, where she died in 1307. It is possible the icons went to Spain with her and ended up in her convent.

The face is astounding in the delicacy and sophistication of the painting. The flesh tones are laid down in very fine brush strokes over a dark green under painting. A rosy tint has been added to the cheeks that fades imperceptibly into the rest of the face. More rose has been added to the eyelids, the base of the nose and the lips. The red is vermilion. Cornea and pupils are drawn in dramatic ellipses that are enlivened with soft gray white highlights. The eye lashes are drawn in black.

The face is astounding in the delicacy and sophistication of the painting. The flesh tones are laid down in very fine brush strokes over a dark green under painting. A rosy tint has been added to the cheeks that fades imperceptibly into the rest of the face. More rose has been added to the eyelids, the base of the nose and the lips. The red is vermilion. Cornea and pupils are drawn in dramatic ellipses that are enlivened with soft gray white highlights. The eye lashes are drawn in black.

Byzantine women of all classes wore make-up and used creams, which were purchased in shops or made at home. Rouge, perfume and eye-liner were essentials. Western visitors remarked on the great beauty of the women of Constantinople and thought their make-up was unnecessary. Fashions changed all the time - styles came from abroad, especially the east. Great beauties were often found in the Trebizond and Georgia and brought to the capital as brides. Islamic visitors claimed all of the shops in the bazaars were run by beautiful women.

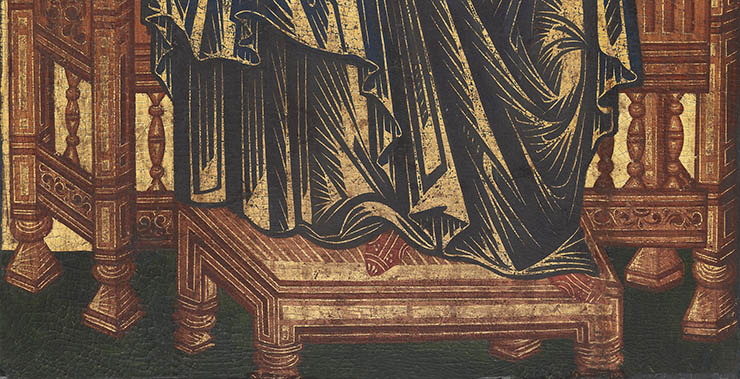

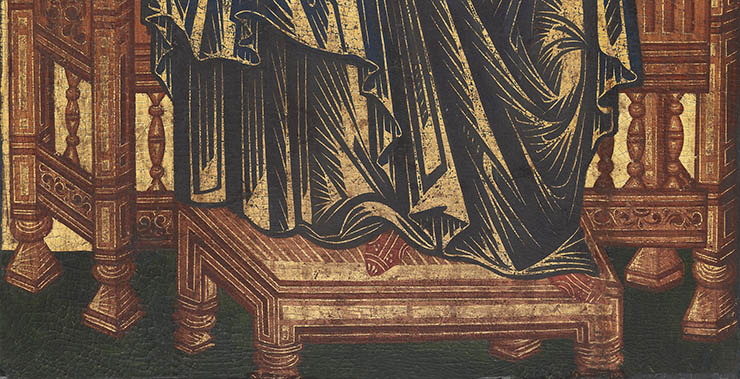

Below are two images of 12th century Byzantine wood furniture, which are identical to the chair in the icon:

The Theotokos looks directly at the viewer while Christ turns to his Mother.

The Theotokos looks directly at the viewer while Christ turns to his Mother.

Christ's hair is very finely done. Notice the small elegant curls on His neck. The patterns in the halos are not incised into the gesso. They were laid on top of a gold background as tiny drops of resin or honey in patterns that was then gilded again. Even the outlines of the halos were created in this way.

Christ's hair is very finely done. Notice the small elegant curls on His neck. The patterns in the halos are not incised into the gesso. They were laid on top of a gold background as tiny drops of resin or honey in patterns that was then gilded again. Even the outlines of the halos were created in this way.

The hair of the Archangel is very finely done (in contrast the Mellon Madonna's are crudely executed. The style of the face is very classical. The angel wears a jeweled ribbon - which could also be called a diadem. In the archangels hands are a staff and a glass ball set with symbols of Christ. The blue of the glass ball has decayed - was it originally Blue Azurite, a pigment that is unstable? Neither of the Archangels has a name. Below you can see where a split in the wood has run right through the face, requiring restoration.

The hair of the Archangel is very finely done (in contrast the Mellon Madonna's are crudely executed. The style of the face is very classical. The angel wears a jeweled ribbon - which could also be called a diadem. In the archangels hands are a staff and a glass ball set with symbols of Christ. The blue of the glass ball has decayed - was it originally Blue Azurite, a pigment that is unstable? Neither of the Archangels has a name. Below you can see where a split in the wood has run right through the face, requiring restoration.

Angels on icons in Imperial regalia died out after the restoration of Constantinople in 1261. As the throne and the court lost power and influence these symbols were no longer popular and the figures return to 'normal' angelic garb. In the last years of the Empire the Crown Jewels were pawned and gilded leather was substituted for solid gold thread embroidery, glass gems replaced real precious stones.

Read more about the Imperial Loros and Diadem in the right-hand column.

Read more about the Imperial Loros and Diadem in the right-hand column.

Above is a 12th century icon of Christ on a curved back wooden throne from Sinai. Here you can also see two circular images of archangel heads. Michael is on the left and Gabriel is on the right. They have fierce looks showing that they are protecting Christ like imperial guards. The medallions have wide red borders. The face of Christ is very similar to the mosaic in the Southern Gallery of Hagia Sophia.

These icons come from the same artistic background as the mosaic of the Deesis in the South Gallery of Hagia Sophia. The Imperial archangels are the genuine expression of an artist who was completely conversant with 12th century court culture. Such works were produced under the supervision of the clergy of Hagia Sophia who ensured that the regalia was accurately depicted. These Imperial vestments were unknown outside Constantinople. The Russians did not reproduce them accurately when they copied icons with these motifs in the 12th century. A close look at the pearl trim of the Loros shows a familiarity with the way the pearls were attached, something only a person who had seen the regalia would understand. Once a year, at Easter, the regalia, crowns and other jewels were displayed in the North gallery of Hagia Sophia to the public. They were under the control of the clergy of Hagia Sophia and the Patriarch. One cannot over emphasize the influence of the clergy of Hagia Sophia on artistic style in Byzantium. The Imperial court was another source of artistic influence in both secular and religious art. This reached in peak during the reign of Manuel I Comnenus. I believe these two icons and the Deesis mosaic were created during his reign.

Below is a comparison of faces of the Virgin from Kahn, Mellon and the Hagia Sophia Deesis.

Technical Specifications:

The icon is painted in egg tempera on a poplar panel, the painted surface is 124.8 x 70.8 cm (49 1/8 x 27 7/8 in.), overall it is 130.7 x 77.1 cm (51 7/16 x 30 3/8 in.). Framed the icon is 130.5 x 77 x 6 cm (51 3/8 x 30 5/16 x 2 3/8 in.) The panel is still set in part of its original engaged frame, which has probably been reduced from its original width. The studs decorating the frame molding are original, although they have been overpainted. There are no markings showing the icon was ever covered with an oklad or decorated revetments.

Below are the colors found in an 1982 analysis of the icon including microscopy and XRF - energy-dispersive x-ray fluorescence:

1. Blue robe of Virgin - ultramarine - Pb Fe, Ca, Cu - ultramarine (est)

2. Red of Christ's robe - vermilion - Hg, Pb, As, Fe, Ca - vermilion

3. Orange footstool - Hg, Pb, Fe, Au, Ca, Cu, Zn - vermilion and lead white

4. Dark green foreground - green glaze with iron oxides; no green particles evident - Cu, As Pb, Fe, Ca - copper green organic; plus orpiment or particles evident 19th-century green.

5. Throne - iron oxides -

6. Bole (under gold) clay

7. Ground gypsum

The chair and footstool are made of wood. Chairs like this very very common and could be found in most homes, even low income households. Byzantine carpenters worked out of established workshops. Furniture was made from all sorts of woods, even rare imported hardwoods. Constantinople was surrounded by great forests of all kinds of trees, many of which were perfect for carving and turning. The common Byzantine home was build with rooms surrounded by benches for cushions and pillows. They also had wooden beds with headboards and footboards. Almost all homes had side chairs and portable tables. Both the Kahn and Mellon Madonnas have the same type of finials along the top. Furniture could be left with natural finishes or painted.

The chair and footstool are made of wood. Chairs like this very very common and could be found in most homes, even low income households. Byzantine carpenters worked out of established workshops. Furniture was made from all sorts of woods, even rare imported hardwoods. Constantinople was surrounded by great forests of all kinds of trees, many of which were perfect for carving and turning. The common Byzantine home was build with rooms surrounded by benches for cushions and pillows. They also had wooden beds with headboards and footboards. Almost all homes had side chairs and portable tables. Both the Kahn and Mellon Madonnas have the same type of finials along the top. Furniture could be left with natural finishes or painted.

Pillows on chairs were often stuffed with aromatic herbs. They were made of woven tapestry or embroidered fabric. Linen or silk-linen or wool was used. Beds were covered with large mattresses with linen coverings.

The state of the painting in 1915 is shown above in the sale catalog published in that year, which shows it unrestored, except for the loss in the gold ground above the Virgin’s head.

The state of the painting in 1915 is shown above in the sale catalog published in that year, which shows it unrestored, except for the loss in the gold ground above the Virgin’s head.

Sometime between 1915 and 1917, before it was sold to Otto Kahn, New York, the work evidently was restored. The various reproductions published from 1917 on show it much darkened by dust and opacified varnishes but without paint color losses. The green foreground at the bottom was repainted.

The icon was a gift to the National Gallery from Mrs. Otto Kahn in 1949.

The Kahn Byzantine Madonna is the finest surviving Byzantine icon. It dates from the 12th century and was painted in a workshop in Constantinople - the capital of the Byzantine Empire. It is large - over 51 inches tall and was discovered in a state of fine preservation. The only damage was two splits in the wood, one above the head of the Virgin and the other on the right which passes through the medallion of the Archangel. The Mellon Madonna came to the National Gallery in 1937 and the Kahn Madonna came 12 years later in 1949.

The Kahn Byzantine Madonna is the finest surviving Byzantine icon. It dates from the 12th century and was painted in a workshop in Constantinople - the capital of the Byzantine Empire. It is large - over 51 inches tall and was discovered in a state of fine preservation. The only damage was two splits in the wood, one above the head of the Virgin and the other on the right which passes through the medallion of the Archangel. The Mellon Madonna came to the National Gallery in 1937 and the Kahn Madonna came 12 years later in 1949. The face is astounding in the delicacy and sophistication of the painting. The flesh tones are laid down in very fine brush strokes over a dark green under painting. A rosy tint has been added to the cheeks that fades imperceptibly into the rest of the face. More rose has been added to the eyelids, the base of the nose and the lips. The red is vermilion. Cornea and pupils are drawn in dramatic ellipses that are enlivened with soft gray white highlights. The eye lashes are drawn in black.

The face is astounding in the delicacy and sophistication of the painting. The flesh tones are laid down in very fine brush strokes over a dark green under painting. A rosy tint has been added to the cheeks that fades imperceptibly into the rest of the face. More rose has been added to the eyelids, the base of the nose and the lips. The red is vermilion. Cornea and pupils are drawn in dramatic ellipses that are enlivened with soft gray white highlights. The eye lashes are drawn in black.

The Theotokos looks directly at the viewer while Christ turns to his Mother.

The Theotokos looks directly at the viewer while Christ turns to his Mother. Christ's hair is very finely done. Notice the small elegant curls on His neck. The patterns in the halos are not incised into the gesso. They were laid on top of a gold background as tiny drops of resin or honey in patterns that was then gilded again. Even the outlines of the halos were created in this way.

Christ's hair is very finely done. Notice the small elegant curls on His neck. The patterns in the halos are not incised into the gesso. They were laid on top of a gold background as tiny drops of resin or honey in patterns that was then gilded again. Even the outlines of the halos were created in this way. The hair of the Archangel is very finely done (in contrast the Mellon Madonna's are crudely executed. The style of the face is very classical. The angel wears a jeweled ribbon - which could also be called a diadem. In the archangels hands are a staff and a glass ball set with symbols of Christ. The blue of the glass ball has decayed - was it originally Blue Azurite, a pigment that is unstable? Neither of the Archangels has a name. Below you can see where a split in the wood has run right through the face, requiring restoration.

The hair of the Archangel is very finely done (in contrast the Mellon Madonna's are crudely executed. The style of the face is very classical. The angel wears a jeweled ribbon - which could also be called a diadem. In the archangels hands are a staff and a glass ball set with symbols of Christ. The blue of the glass ball has decayed - was it originally Blue Azurite, a pigment that is unstable? Neither of the Archangels has a name. Below you can see where a split in the wood has run right through the face, requiring restoration.

The chair and footstool are made of wood. Chairs like this very very common and could be found in most homes, even low income households. Byzantine carpenters worked out of established workshops. Furniture was made from all sorts of woods, even rare imported hardwoods. Constantinople was surrounded by great forests of all kinds of trees, many of which were perfect for carving and turning. The common Byzantine home was build with rooms surrounded by benches for cushions and pillows. They also had wooden beds with headboards and footboards. Almost all homes had side chairs and portable tables. Both the Kahn and

The chair and footstool are made of wood. Chairs like this very very common and could be found in most homes, even low income households. Byzantine carpenters worked out of established workshops. Furniture was made from all sorts of woods, even rare imported hardwoods. Constantinople was surrounded by great forests of all kinds of trees, many of which were perfect for carving and turning. The common Byzantine home was build with rooms surrounded by benches for cushions and pillows. They also had wooden beds with headboards and footboards. Almost all homes had side chairs and portable tables. Both the Kahn and  The state of the painting in 1915 is shown above in the sale catalog published in that year, which shows it unrestored, except for the loss in the gold ground above the Virgin’s head.

The state of the painting in 1915 is shown above in the sale catalog published in that year, which shows it unrestored, except for the loss in the gold ground above the Virgin’s head.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints