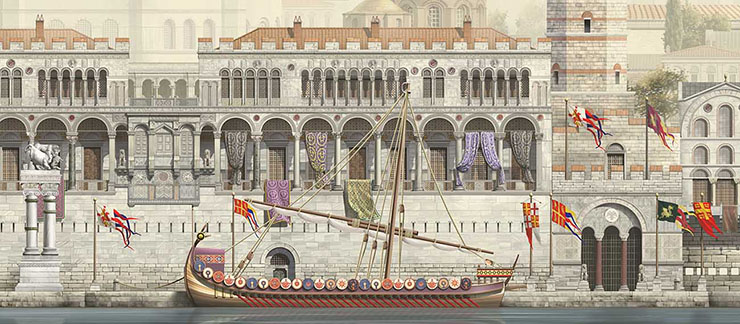

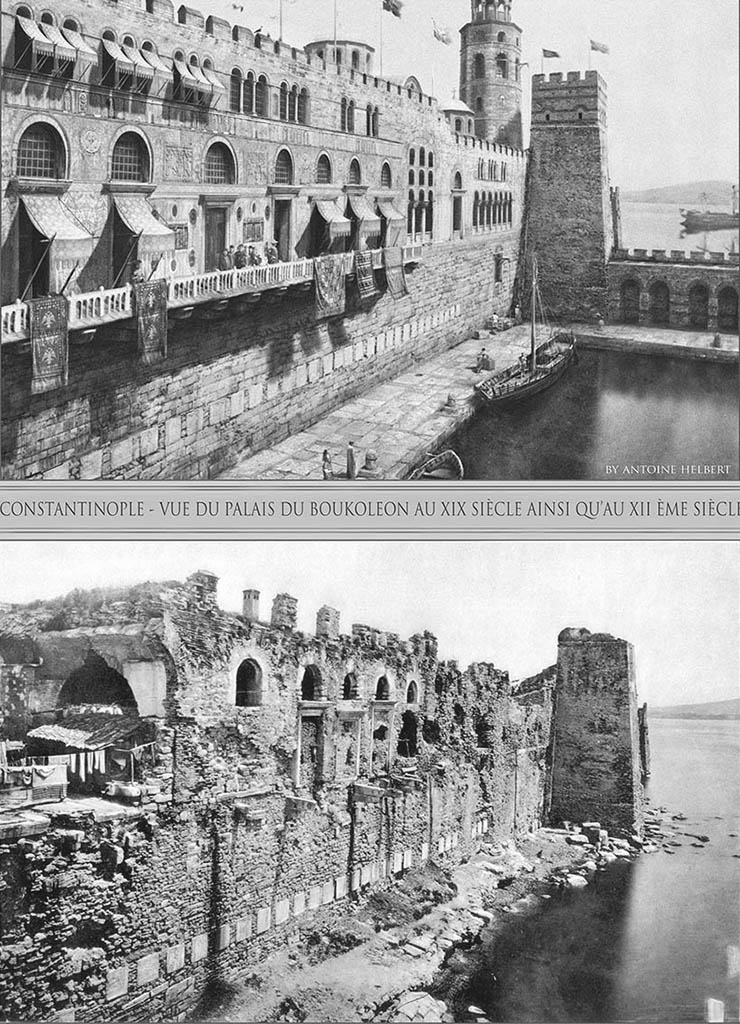

This Varangian Guard is standing outside the Boukoleon Palace, which was decorated with statues of lions and bulls. You can see banners on the right.

This Varangian Guard is standing outside the Boukoleon Palace, which was decorated with statues of lions and bulls. You can see banners on the right. Here we see a guard and court official standing in the courtyard of the Blachernae Palace. He might not be a Varangian because he is not carrying an axe. That strange white hat was actually worn in late Byzantine times. Byzantine peaked hats were widely admired abroad.

Here we see a guard and court official standing in the courtyard of the Blachernae Palace. He might not be a Varangian because he is not carrying an axe. That strange white hat was actually worn in late Byzantine times. Byzantine peaked hats were widely admired abroad. The Chalke Gate of the Great Palace had a high dome over it like this one.

The Chalke Gate of the Great Palace had a high dome over it like this one.

Andronikos Escapes Yet Again - Sexual Exploits and Excesses

At this time, Andronikos, who had escaped once again [1164] and come to Galitza, returned from there [spring 1165]; Galitza is one of the districts of the Rhos who are called Hyperborean Scythians. His manner of escape was as follows.359 He pretended to be ill and was provided with a young boy to attend to his physical needs, a foreigner who largely mispronounced our speech. Andronikos knew that there was only one entrance into the prison. He instructed the boy to stealthily remove the keys to the tower gates when the guards, overcome with copious drink, were taking their daily nap and to make a wax impression of them so that the impress should be in every way identical to the original in shape and form. The lackey did as he was commanded and brought the wax impressions to Andronikos. The latter directed the young attendant to present these to his son Manuel and to tell him that it was imperative that he forge keys from them as quickly as possible; moreover, he was to insert into the amphorae of wine which held his drink for his midday meals small ropes of twisted linen fibers and balls of thread, together with woolen yarn and slender cords. When these instructions were carried out, at a signal from Andronikos the boy lifted the bars of the prison gates during the night, and the gates were thrown wide open without any trouble. Then Andronikos, holding the cords in his hands, let himself down into the thick weeds growing high in the impassable parts of the palace grounds.  During the second and third days he continued to escape the detection of his pursuers by hiding in the tall grass. Once they were satisfied with their search of the palace environs, Andronikos made a ladder of wooden rungs and let himself down over the wall between the two towers. At a prearranged signal he boarded a boat pitching between the shore and the breakwaters found at intervals along the City's sea wall which dissipated the impact of the breaking waves. The name of the man who received Andronikos into the fishing boat was Chrysochoopolos. But before they could put out to sea they were apprehended by the officers of the guard who stand on lookout along the Boukoleon to protect the palace from attack by approaching ships.

During the second and third days he continued to escape the detection of his pursuers by hiding in the tall grass. Once they were satisfied with their search of the palace environs, Andronikos made a ladder of wooden rungs and let himself down over the wall between the two towers. At a prearranged signal he boarded a boat pitching between the shore and the breakwaters found at intervals along the City's sea wall which dissipated the impact of the breaking waves. The name of the man who received Andronikos into the fishing boat was Chrysochoopolos. But before they could put out to sea they were apprehended by the officers of the guard who stand on lookout along the Boukoleon to protect the palace from attack by approaching ships.  This lookout dated from the time when John Tzimiskes attacked Nikephoros Phokas after being drawn up in a basket at this spot. Andronikos very nearly ended up in prison once again, with his hands bound in chains or slain by the sword, and thus spared the many wanderings that followed. But now ready Wit saved the resourceful man, cutting and gathering from her own garden fitting medicinal herbs to cure the ills of the times, just as David was preserved from danger in Geth by altering his appearance and beating on the drum and crazily jerking his legs. Pretending to be a household slave fleeing the bonds of many years,

This lookout dated from the time when John Tzimiskes attacked Nikephoros Phokas after being drawn up in a basket at this spot. Andronikos very nearly ended up in prison once again, with his hands bound in chains or slain by the sword, and thus spared the many wanderings that followed. But now ready Wit saved the resourceful man, cutting and gathering from her own garden fitting medicinal herbs to cure the ills of the times, just as David was preserved from danger in Geth by altering his appearance and beating on the drum and crazily jerking his legs. Pretending to be a household slave fleeing the bonds of many years,

Andronikos pleaded with his captors to have compassion on him for the many tribulations he had suffered in the past at the hands of his master and for the punishment that would be inflicted on him now because of his escape. He named Chrysochoopolos as his owner and spoke in barbarian speech instead of the Greek tongue, pretending he did not understand the latter very well. Chrysochoopolos, for his part, deceived the sentinels with gifts and was able to free Andronikos, claiming him as his runaway slave. Thus Andronikos so unexpectedly arrived unnoticed at his own home, called the House of Vlangas, and saluted his dearest family as he made his entrance. When the shackles were removed from his legs, he announced that he was going abroad. At Melivoton he mounted the horses which had been made ready for his escape and raced straight for Anchialos, where he presented himself before Poupakes, who, as I have stated above, first scaled the ladder at Korypho [Corfu]. After receiving provisions and guides to show the way, he took the road to Galitza.

But just when Andronikos began to feel safe because he had slipped through his pursuers' hands and reached the borders of Galitza, towards which he had hastened in search of a place of refuge, he fell into the hunters' snares. Apprehended by the Vlachs, who had heard rumors of his escape, he was led back to the emperor.

With no one to rescue or redeem him and no bodyguard, attendant, or friend along to console him, the ingenious fellow resorted to his own wiliness. To deceive his abductors, he pretended to suffer from gastroenteritis and day and night would frequently dismount and turn aside to defecate, withdrawing alone at a distance on the pretext that he did not wish to disturb the others. Rising up in the dark of the night, he planted in the ground the staff which he used to support himself when presumably he was indisposed and wrapped his cloak around it; he placed his hat on top and, forming it into the shape of a man bending his knees and dis- charging excrement, outwitted his guards. While they watched the dummy, he took cover in the copse and saved himself by fleeing like a gazelle from the noose, like a bird from the snare. When his abductors finally realized that they had been tricked, they charged ahead, supposing that Andronikos would go by the same road he had taken earlier, but he turned back and went by another route to Galitza.

The emperor arrested Poupakes and had him publicly scourged until the many blows of the lash lacerated his back and shoulders. Afterwards, the herald, leading him about with a rope around his neck, shouted the following: "Whosoever harbors the emperor's enemy and sends him on his way with provisions will be flogged and paraded about in the same way." Poupakes looked intently at the assembled populace with a joyous countenance and responded: "Let my shame be before every man who so wishes for not having betrayed my benefactor who came to me, for not having dismissed him harshly, but instead attending rightly to his needs and sending him rejoicing on his way."

Andronikos was welcomed by the governor of Galitza with open arms and remained near him for a long time [1165-66]. He so endeared himself to the governor that he joined him in the hunt, was his partner in deliberations, and shared the same hearth and table with him.

Emperor Manuel judged his cousin's flight and alienation from his own homeland to be a reproach against himself. Moreover, he viewed his prolonged absense with suspicion because it was rumored that Andronikos was attracting a myriad of Cuman horse in order to overrrun the Roman borders and thus gave, they say, Andronikos's return highest priority over all other business. He summoned him thence, and they exchanged pledges of good faith, and he embraced the vagabond, this at the same time the Hungarians, violating their treaties, were ravaging the Roman provinces along the Danube....

Thus did these events unfold. Since Manuel had not yet begotten a son [end of 1165 or beginning of 1166], he fixed the succession on his daughter Maria, whom his German wife had borne him, and bound everyone by sworn oaths to recognize Maria and her husband Alexios, who, as we have said, came from Hungary, as heirs of his throne and to submit and make obeisance to them as emperor and empress of the Romans after his death. While all others acknowledged the designated heirs and gave their sworn oaths as commanded by the emperor, Andronikos was reluctant, saying, "The emperor may be inclined to enter into a second marriage from which, presumably, he may beget a son, and by binding ourselves afterwards on oath to secure the throne for the em- peror's younger offspring, we will be compelled to violate the oaths just taken on behalf of the emperor's daughter." He continued, "What madness is this of the emperor to deem every Roman male unworthy of his daughter's nuptial bed, to choose before all others this foreigner and interloper to be emperor of the Romans and to sit above all as master?" The emperor was not persuaded by this sound advice, taking Andronikos's words as idle prattle spoken by a man who was both contrary and obstinate. There were those who, after the oath-taking ceremony, made common cause with Andronikos; some declared on the spot their support of his views, while others argued that it was not to the advantage of either the emperor's daughter or the Roman citizenry to graft onto the fruitful and good olive tree the branch from an orchard of another species with the intention of girding others with power.

The following memorable event ought not to be omitted from this history. This emperor was very concerned about the cities and fortresses of Cilicia, over which the shining and renowned Tarsus presides as metropolis. Consequently, after many illustrious governors of noble blood had been assigned there, the lot finally fell to Andronikos Komnenos, who was both of the highest nobility and the handsomest of men [1166]. There he collected the tribute from Cyprus, which provided his operating expenses. He conceived a hatred for Thoros [II], who, in turn, thoroughly despised him, and declared war on Thoros, often opposing him in battle. Andronikos accomplished no noble action whatsoever, nor did he perform any noteworthy deed, despite his versatile experience in warfare and cunning ways. Finally, after Thoros had inflicted a shameful defeat on him and had set up a trophy, he decided on a most reckless action which I shall now relate.

In Antioch, Andronikos gave himself over to wanton pleasures, adorned himself like a fop, and paraded in the streets escorted by bodyguards bearing silver bows; these men were tall in stature and sported their first growth of beard and blond hair tinged with red. Henceforth Andronikos pursued his quarry, bewitching her with his love charms. He was lavish in the display of his emotions, and he was endowed, moreover, with a wondrous comeliness; he was like a young shoot climbing up a fir tree. The acknowledged king of dandies, he was titillated by fine long robes, and especially those that fall down over the buttocks and thighs, are slit, and appear to be woven on the body. But his manliness was diminished, and he was constantly anxious; he lost his sobriety and faculty of reason, and the beast of prey shed his gravity of deportment. Philippa, utterly conquered, consented to the marriage bed, forsook both home and family,394 and followed after her lover.

Thunderstruck and almost speechless on learning of Andronikos's doings, Manuel decided to deal with both parties. He detested Andronikos for his indecent love affair and unlawful marriage, and because he had dashed his hopes against the Armenians, he wanted him seized and punished. He dispatched the sebastos, Constantine Kalamanos, a man of reason, daring, and steadfast nobility of mind to attend to the affairs of Armenia and also to make an attempt to wed Philippa [1166]. Kalamanos, bedecked in splendid attire as befits a groom and confident that he would win over the inamorata, entered Antioch. So devoted was Philippa to Andronikos, and so successful was he in wooing her away from her first love, that she did not give Kalamanos a second look or deign to address him by name. Instead she berated him for being short, and de- rided Manuel in front of him for being so stupid and simple-minded as to think that she would forsake the hero Andronikos, whose fame was wide- spread and who was descended from a great and noble family, and cleave to a man who, as was well known, came from an obscure family line which had made its appearance but only yesterday.

When Constantine saw that he was held in low esteem by Philippa's Erotes, who fluttered their wings towards another, pelting Andronikos with apples and carrying torches, he departed and went to Tarsus, where he engaged the Armenian enemy in battle with his Romans. As they had done in the past, the adversary pressed him closely, then took him captive, and bound him in chains. The emperor gained his release by paying a large ransom.

Andronikos, fearing Manuel's threats and anxious lest he be taken prisoner, thus to exchange Philippa's embraces for his former prison and endure long-lasting suffering, departed and took the road to Jerusalem [beginning of 1167], exposed like the proverbial weasel accused of chasing after the suet. He returned to his former life as a renegade and relied on the wiles he had used in the past.

Like a horse in heat covering mare after mare beyond reason, his behavior was promiscuous, and he engaged in sexual intercourse with Theodora, comporting himself with unbridled lewdness. Theodora was the daughter of his first cousin (I speak of Isaakios the sebastokrator, Emperor Manuel's brother); the husband of her maidenhood, Baldwin, an Italian by race, had reigned over Palestine earlier but had recently died [1163]. Manuel, suffering yet another affront as a result of his behavior, devised all manner of schemes in the hope of catching Andronikos in his nets and dispatched a letter written in red ink urging the authorities of Coele Syria to seize Andronikos as a rebel guilty of incest and put out his eyes.

Like a horse in heat covering mare after mare beyond reason, his behavior was promiscuous, and he engaged in sexual intercourse with Theodora, comporting himself with unbridled lewdness. Theodora was the daughter of his first cousin (I speak of Isaakios the sebastokrator, Emperor Manuel's brother); the husband of her maidenhood, Baldwin, an Italian by race, had reigned over Palestine earlier but had recently died [1163]. Manuel, suffering yet another affront as a result of his behavior, devised all manner of schemes in the hope of catching Andronikos in his nets and dispatched a letter written in red ink urging the authorities of Coele Syria to seize Andronikos as a rebel guilty of incest and put out his eyes.

If the imperial letter had been delivered, and Andronikos taken captive and bound in chains, surely his eyes would have been stained red with blood, and pallor would have laid hold of his cheeks, or he would have succumbed to dark death."0° But he was protected by God, who, it seems, was storing up against the day of wrath' the evils that Andronikos later visited intemperately upon his subjects when he reigned as tyrant over the Romans and the horrors which, without pity, were visited upon him. The dispatch fell into Theodora's hands. Reading it, she grasped the mischief being concocted against Andronikos and handed the document over to him at once.

Now Andronikos realized that it was necessary to make a hasty departure and that there was no time to loiter. A feeling of horror came over him, and he set about to make his escape. A dissembler and a cheat, he tricked Theodora into leaving the security of her household, just as Zeus in days of yore led Europa astray from the chorus of virgins and carried her off on his back by changing into a bull with magnificent horns; he asked her to accompany him. the distance of a sabbath day's journey so as to bid him farewell and then dragged her willy-nilly after him to be his companion and fellow wanderer.

Andronikos roamed far and wide, from province to province, the guest of rulers and princes who held him in esteem and thought him worthy of their greatest benevolence. His wandering finally came to an end when he came to the realm of Saltuq, whose principality then included the borderlands of Koloneia and who enjoyed the fruits of the lands adjacent to Chaldia and nearby. There Andronikos dallied away the time with The- odora and the two children she bore him, Alexios and Irene. John, the legitimate offspring of his former marriage, had come from Byzantion to keep him company only to return to Emperor Manuel, as shall be recorded at the proper and fitting time in this history in connection with Andronikos's subsequent actions. Manuel tried repeatedly to ensnare Andronikos and take him captive, but he was attempting the impossible, for the ever-roving and stouthearted Andronikos could ward off attacks against him as though they were children's blows, and, leaping nimbly over the many traps set to ensnare him, he remained at liberty.

What happened next? Nothing must be omitted from these events. Every man who holds power is fearful and suspicious; each rejoices in executing the works of Thanatos and Chaos and Erebos, felling the nobility, overturning and casting forth as excrement the influential and capable counselor, and cutting down the courageous and ingenious general. The mighty of the earth can be likened to lofty and tapering pine trees; just as these rustle when the sharp winds shake the needles of their branches, so do these rulers mistrust the man of wealth and cower before him who surpasses most in manly spirit. And should there exist someone endowed with the beauty of a statue and the lyrical eloquence of a nightingale in song, gifted, moreover, with ready wit, then the wearer of the crown can neither sleep nor rest, but his sleep is interrupted, his voluptu- ousness suppressed, his appetite for pleasure lost, and he is filled with grave apprehensions; with wicked tongue he curses the creator nature for fashioning others suitable to rule and for not making him the first and last and the fairest of men. Such rulers oppose providence and behave insolently toward the Deity. As victims they slay the best from among the people so that undisturbed they may waste and squander in luxury the public revenues as though they were their own private patrimony and treat free men as slaves and, at times, behave towards their most competent ministers as though they were purchased slaves. These men are ignorant of what is right, deprived of prudence by their abuse of power, and foolishly oblivious of their former condition.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints