From O City of Byzantium by Niketas Choniates

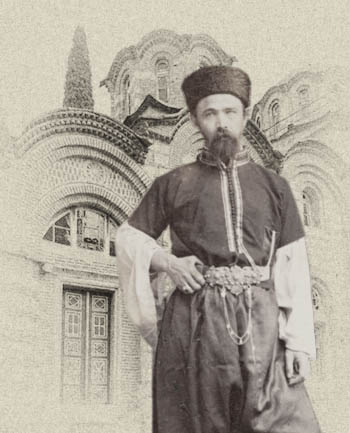

THUS Isaakios Angelos succeeded to the throne with no trouble whatsoever by purchasing it, so to speak, with the blood of Hagiochristophorites. He left the Great Palace and arrived at the palace of Blachernai, where he played the role of the righteous man most masterfully, continually repeating the verses which were said of the bovine emperor and mistakenly applying them to himself.

THUS Isaakios Angelos succeeded to the throne with no trouble whatsoever by purchasing it, so to speak, with the blood of Hagiochristophorites. He left the Great Palace and arrived at the palace of Blachernai, where he played the role of the righteous man most masterfully, continually repeating the verses which were said of the bovine emperor and mistakenly applying them to himself.

"The form shows forth the place and the manner

Whence you came, proving to me what a friend you are; Being yourself temperate, you teach your dearest friends self-control;

Earning alone the glory that emanates from the palace,

By taking the sovereignty from the dying man, 0 most excellent one;

And shortly you shall prosper in the rule."

As emperor, he anointed his head with an abundant measure of compassion for the indigent, and behind his closet door he held converse with God the Father who sees in secret."'a All those who had suffered afflications in exile and those whom Andronikos had stripped bare of their properties or whom he had physically maimed Isaakios gathered together and rewarded with substantial benefactions, restoring whatever of their possessions had been kept hidden in the imperial treasury and had not disappeared or which, awarded by Andronikos to others, still survived. In addition, he greeted them with a generous hand and provided large sums of money from the palace treasuries.

He also directed the war against the Italians, who had already taken Thessaly and Amphipolis. Unreservedly emboldened, they boasted that they would easily subdue the megalopolis by land and by sea, that they would occupy her as a deserted nest and, within a few days, effortlessly plunder her. The people looked upon Isaakios's reign as the transition from winter to spring, or as the steady calm following the storm. They came streaming in from all parts of the Roman provinces, not only those under arms but also those who had been disabled in the past, and the youths no less; some came only to look upon the liberator Moses and Zorobabel leading back the captives of Sion (for thus did they deem Isaakios), others to receive their customary soldiers' pay, and some to enlist in the army and to acquit themselves like men against the Sicilians. When Andronikos's downfall became known to those who marched away together with Andronikos's son, Emperor John, to the province of Philippopolis, they immediately seized him and gouged his eyes out. Waiting for someone to console him and finding no one, and for someone to grieve with him and beholding no one, he died an agonizing death.

He also directed the war against the Italians, who had already taken Thessaly and Amphipolis. Unreservedly emboldened, they boasted that they would easily subdue the megalopolis by land and by sea, that they would occupy her as a deserted nest and, within a few days, effortlessly plunder her. The people looked upon Isaakios's reign as the transition from winter to spring, or as the steady calm following the storm. They came streaming in from all parts of the Roman provinces, not only those under arms but also those who had been disabled in the past, and the youths no less; some came only to look upon the liberator Moses and Zorobabel leading back the captives of Sion (for thus did they deem Isaakios), others to receive their customary soldiers' pay, and some to enlist in the army and to acquit themselves like men against the Sicilians. When Andronikos's downfall became known to those who marched away together with Andronikos's son, Emperor John, to the province of Philippopolis, they immediately seized him and gouged his eyes out. Waiting for someone to console him and finding no one, and for someone to grieve with him and beholding no one, he died an agonizing death.

His brother Manuel was also arrested and blinded, despite the fact that he in no way assented to his father's crimes and that this was well known, not only to those who frequented the agora but above all to Isaakios, who deprived him of his sight.

When Isaakios saw the considerable concourse of people from the eastern cities who came to take part in the campaign against the Sicilian enemy, he welcomed them readily and gladdened them with as many gifts as possible. Then he armed them and dispatched them to the army under Branas's command. To the Roman divisions in the field who fought the enemy troups, he sent the imperial rations and gave added support to the struggle at hand to the sum of four thousand pounds of gold.

The Sicilian adversary had not yet heard of Andronikos's fall and confidently continued their advance, intending to terminate their march at Constantinople; their fleet sailed out and put in at the islands nearest the City. But He who does not allow the Giants to be saved by the greatness of their strength and by war chariots and horses, and showers His grace on the humble, caused the proud to fall. Coming down once again in truth, He did not confound their tongues but divided them into three parts. The one part was left to keep watch over the presiding city of the Thessalians [Thessaloniki] and remained in force with the support of fast-sailing ships; the second part plundered the territory around Serrai with impunity; the third part did not remain wholly undivided, but one section drank and bathed in the Strymon while laying waste the lands around Amphipolis, and the other, advancing joyfully as though anticipating their entry into the capital, encamped at Mosynopolis. Ever victorious and meeting absolutely no resistance, they made reckless sallies. They separated according to companies, each going its separate way, and scattered in the hope of despoiling anyone coming out of, or carrying provisions into, Mosynopolis.

The strategos Branas observed the activities of the barbarians in those parts and led on the army from time to time, but he could barely persuade the troops to come out of the mountains but for a little and take to the plain fit for driving horses. In their first attack they performed bravely and routed an enemy division, bearing out the myth of the Myrmidons""' in their own actions; they were suddenly transformed into men of valor and ever cut down those in the rear ranks. The rout of the enemy continued all the way to Mosynopolis. After successfully engaging the enemy before the city, they attacked the defenders within. They set fire to the gates guarded by the enemy (for fear and shuddering had already compassed their bodies), and, leaping inside, they reveled in slaughter, having for so long been starved of the savory repast of warfare. As they consumed the wealth of the nations, they were surfeited and made fat by the booty, and they became presumptuous over against the enemy around Amphipolis, passing over their recent victory as though it were stale food.

They marched, therefore, in battle array, as though they were the Camp of God, or an army of lions, against the horses, armaments, and remaining divisions of the enemy still encamped about the Strymon. When the die of fortunes was cast contrariwise by the hand of God, they, who were formerly haughty and disdainful, boasting that they could well- nigh lift up and move mountains with their lance, were as though struck by lightning or by the violent crash of thunder. Driven mad by the dreadful reports of what had befallen their near friends at Mosynopolis, they procrastinated in giving battle and sluggishly drew themselves out in battle order. The Romans, on the other hand, putting aside their humility of spirit and darting forth like eaglets dwelling high in the clouds in pursuit of fowl on the ground, raced with wingless speed to engage in battle those who had formerly reproached them as having turned into birds.

They marched, therefore, in battle array, as though they were the Camp of God, or an army of lions, against the horses, armaments, and remaining divisions of the enemy still encamped about the Strymon. When the die of fortunes was cast contrariwise by the hand of God, they, who were formerly haughty and disdainful, boasting that they could well- nigh lift up and move mountains with their lance, were as though struck by lightning or by the violent crash of thunder. Driven mad by the dreadful reports of what had befallen their near friends at Mosynopolis, they procrastinated in giving battle and sluggishly drew themselves out in battle order. The Romans, on the other hand, putting aside their humility of spirit and darting forth like eaglets dwelling high in the clouds in pursuit of fowl on the ground, raced with wingless speed to engage in battle those who had formerly reproached them as having turned into birds.

When both armies converged on the same position (it was called the place of Demetritzes), then more and more the Sicilians demonstrated their cowardice. They decided to sue for peace, and to this end they sent an envoy to enter into negotiations with Branas. At first, the request delighted the Romans; shortly afterwards, however, they changed their minds, suspecting that the enemy's proposals were a stratagem, and if this were not the case, it was undoubtedly evidence of cowardice. Without waiting for the call to battle or the sounding of the war trumpet or any other mobilization order customarily given by commanders before battle, they attacked the enemy with swords bared. Up to a certain point the Sicilians received the charge of the Romans bravely and courageously, and the tide of battle ebbed and flowed, but finally they succumbed to the excessively impassioned charge of the Roman troops; they turned their backs and fled in disorder. When overtaken, they were cut down, taken captive, driven into the Strymon River, plundered, and stripped. It was in the early afternoon of the seventh day of the month of November when these events took place [1185].

Both generals of the army were apprehended: Richard, the brother of Tancred's wife, who commanded the Sicilian fleet, and Count Baldwin, who was not descended from a noble and illustrious family but was highly regarded by the king for his competence in military science; he was, above all others at that time, girt with the dignity of generalship. Exulting in his earlier victories over the Romans, he likened himself to Alexander the Great, the Macedonian, except that he did not have on his chest, as did Alexander, hairs depicting a beak and representing wings," and he boasted of having achieved even greater deeds than Alexander in a briefer span of time and without bloodshed.

Those troops who had escaped the net of battle that had been cast, together with those who had overrun the lands around Serrai, hastened straightway to Thessaloniki and embarked on the long boats as soon as they arrived from their hasty flight. But they were not to have a fair voyage; furious storms that bore their destruction rose up to cripple them and worked their doom, which was first ordained by the will of God to take place on land and then, shortly afterwards, at sea. Many who were too late for the triremes were overtaken while still wandering about Thessaloniki and put to death in diverse ways, especially by the Alan mercenaries. In retaliation for what they had suffered when Thessaloniki fell, they took no pity upon the enemy and filled the streets and the narthexes of the holy churches with corpses. As they asked the captive Sicilians, "Where in the world is my brother? (they meant their fellow Alan whom the Sicilians had killed during the fall), they ran them through with the sword. They also slaughtered those who streamed into the temples, with the words, "Where in the world is the papas?" [father] meaning those priests killed when the Sicilians had burst in upon the sanctuaries.

At this time something quite novel took place. They say that after the fall of the city, the dogs did not snatch at the corpses of the slain Romans, or rend them with their teeth, or mutilate them, but they attacked the bodies of the fallen Latins with such viciousness, unsatiated by the flesh they devoured, that they even broke into graves and unearthed the entombed bodies as prey.

The two generals of whom we have spoken and the brainless and pernicious Alexios Komnenos, the cause of all these evils, who deserved to dwell in the House of Charon, were deprived of the light of their eyes.

The two generals of whom we have spoken and the brainless and pernicious Alexios Komnenos, the cause of all these evils, who deserved to dwell in the House of Charon, were deprived of the light of their eyes.

The Latins who reached Epidamnos safely were gladly delivered over to their countrymen who guarded the city as the seeds of many thousands. The king of Sicily, having strengthened its defenses with all manner of weapons, would not deliver the city over to the Romans after the destruction of his armies. In foolish pursuit of famed glory, he insanely held on even after suffering defeat and disgrace. But not long afterwards, because provisions were scarce, he decided to withdraw.

The auspicious conclusion of the land war was such as had never entered our hearts. But God, as ruler over all, cares for all; governing human affairs with great forebearance and taking pity on all things, for he can do all things, he tipped the scales in our favor. Bringing every good hope, and chastening us but briefly, he scourged our enemies ten thousand times more, neither by changing the harmony of the elements, nor by bringing lice forth from the earth, nor by casting up fish and frogs from the river, nor by sending wasps forward as forerunners of the host, nor by any of the other prodigies of old; but rather, they who were being killed were suddenly transformed by God into relentless warriors and began to slay the murderers, for wickedness is a vile thing condemned by its own witness,"" and, pressed by its own conscience, it ever suffers the most grievous consequences.

For what grave charge could the Sicilians, removed from us by shadowy mountains and sounding sea, lay against the Romans? And should we seek to apprehend the deeper judgments of God, the Lord smites us because he knows our sins. Because those who, by the will of God, laid hold of us to flog us were both reckless and merciless, they, too, did not escape the just wrath of him who will have mercy and in measure feeds us the bread of tears and gives us tears to drink. But, as a lion leaping out of a thicket, like the destructive whelps of a wolf, and like a pouncing leopard, the captors became captives and the victors were vanquished, and the Lord had prepared for them a spirit of error that revealed the red-colored stains caused by their murderous ways and in need of cleansing. They crossed their own borders and invaded our lands; flogging us for a short time, they were flogged much more.

Thus did Justice take vengeance on the cavalry. The long ships, more than two hundred in number, also did not escape unscathed as they backwatered. Where they attempted to put their passengers ashore along the Astakenos Gulf, many were lost as they encountered the Roman forces who prevented them from bringing their ships to land by taking up positions on both shores, thus making it impossible to set foot on either side. Whenever the Sicilian fleet approached land or let down the gangway, a deluge of missiles immediately rained down upon them from all sides, and everyone ran for cover beneath the ships's decks even as turtles withdraw into their shells. Their ships were numerous, but ours, number- ing no more than one hundred in all, were eager to give battle. Not only was the fleet heartened but also many of the City's inhabitants, who boarded fishing boats and armed themselves with whatever weapons were at hand, throbbing with eager excitement to sail out against the enemy. The public interest did not induce the emperor and his counselors to give their permission for this; the fact of the excessive numbers of the enemy ships had to be considered. Consequently, our triremes riding at anchor alongshore the Columns [Diplokionion] did not advance any further. The enemy's fleet did not take to the oar and move out from the islands for some seventeen days, since they saw none of our countrymen approach- ing by land; considering the delay not to their advantage, they prepared to set sail [November, 1185]. After wasting with fire the island of Kalonymos and the littoral of the Hellespont as well, the fleet sailed homewards. It is said that many ships, men and all, sank in the deep when they encountered tempestuous winds, while famine and disease emptied out others.

Thus, no less than ten thousand fighting men were lost in these campaigns. The captives taken in both battles, numbering more than four thousand, were incarcerated in public prisons. Had they not been fed from the imperial treasuries or had they not received the necessities of life from some other quarter, and been forced to survive only on bread provided by those God-loving people who visit those in prison, they would have wasted away miserably. He who wielded the scepter over Sicily and had initiated the war against the Romans, when informed of these things, sent letters reproaching the emperor for his lack of mercy and for cruelly allowing so many ranks of men of such tender age to perish of hunger and nakedness. Certainly they had taken up arms to wage war against the Romans, but nonetheless, they were Christians delivered into their hands by God. The victor, he said, either should have immediately condemned the prisoners to utter destruction, wholly irrationally exchanging his own nature for that of the beast and disregarding the law of humanity, or, choosing not to behave in this manner and casting them into prison, he should have broken bread for them consisting of eight pieces if he were too niggardly to provide sufficient sustenance. The emperor took no heed of the letters' contents. He allowed the wretches to waste away as before, which was the fate he had in store for them. Every day, two and three at a time were often carried out and, deprived of burial rites and libations to the dead, were thrown into the common burial places and deep pits.

The emperor, vested in his jeweled toga and seated on his royal throne inlaid with gold, assembled a multitude around his tribunal, so that he appeared most formidable to both foreigners and Romans, and commanded the generals of the Sicilian army, that is, Baldwin and Richard, to be brought before him. After they had removed their head coverings and rendered servile obeisance, they were questioned by the emperor as to why they had reviled him, the anointed of the Lord,"" who had given no just cause for complaint. Gloating all the while over their present plight, more than was proper, he boasted and exulted in the crushing defeat of the enemy.

At the time the Latin army was still intact and Emperor Isaakios had but just succeeded to the throne. He dispatched envoys, but he made no offer of reconciliation to the generals, or honored them with gifts, or led them on with any pretences of goodwill. He addressed them in an imperious manner, and, smiting them with reproaches and accusations, he bore himself pompously towards men who were still victorious and who had trampled under foot the entire realm of the Romans. Openly praising and extolling his sword with its lethal power, he violently threatened-without yet knowing how he was going to achieve it-their utter destruction and perdition if they did not alter their plans and return whence they had come.

Baldwin, an arrogant man now swollen like a wineskin because of his successes, could not tolerate these written communications. He replied most cleverly to the emperor: he ridiculed his sword as having been honed on the bodies of effeminate men (he was alluding to the death of Hagiochristophorites), and he mocked Isaakios as being helpless, for he had never camped out and slept on a shield, or endured a helmet covered with coal dust and abided a filthy coat of mail. Instead, from a tender age, he had devoted himself to an elementary schoolmaster; he had been taught learned trifles, holding in his hands a pencil and a writing tablet and with a parchment dealing with numbers hanging about his person; he had looked askance at the scourge which fell frequently on hands and buttocks and had known and feared only the crack of the whip, without ever experiencing the threat of Ares or ever hearing the hurtling of spears. Not only did Baldwin write these things in mockery but he also resorted to persuasion; although he was an enemy, he became a counselor. He urged Isaakios to put away the imperial crown and to lay aside the remaining insignia of sovereignty, and, folding these away, to give up all claim to them and to preserve them for the winner and the better man, thus referring to the king as his master, and to fall down before him and plead long and urgently for his life only.

Because of these things, the emperor now brought the generals to account, dismissing from his mind the verse of David, "Our tongue is our own: who is lord over us? and he condemned them to death because of what they had written.

Baldwin, skillfull in casting reproaches while extolling his successes, was also an inordinate flatterer who assigned the emperor's failure to the slight inferiority of his weapons and engines of war. He deflected the emperor's wrath and mollified his anger by first magnifying his sword as being truly imperial and keen and then contending that the words written by the emperor at that time were words of truth that had been sealed indeed by the hand of God and were not empty, light talk. He pleaded that he did not deserve being cast aside as worthless, despite the bitter words he had written, for even Nature considers hatred among enemies as blameless.

Wherefore the emperor remained silent, adding nothing more. I know not whether he was swayed like a woman by the flattery or persuaded by the statement of defense.

Baldwin and Richard were again placed under guard when they left. The emperor, now turning his attention to other matters, gave explicit instructions to those present and to all the rest that from that day on he wished no one to be maimed in body, even though he be the most hateful of men, and even though he plot to take the emperor's life and throne. All those assembled at the imperial tribunal applauded this declaration and shouted in approval almost as it they were listening to the voice of God. All, contemplating the difficulty of accomplishing what was promised and amazed at his excessive gentleness, remarked that the emperor was the perfect gift from God. It is not possible that someone, especially an emperor, should be characterized by an immutable depravity of nature which cannot be altered or changed for the better, or that he should shelter a rebellious man who lays thieving hands on the throne, even though he should put forth special claim to virtue and with David should not requite with evil those who requite him with good, 1065 or, in times of danger, should chant his verses, "They compassed me about as bees do a honeycomb, but in the name of the Lord I repulsed them. Shortly afterwards, however, the emperor gave indications of contradicting the resolution he had declared in public; just as he gave no explicit verbal commands, neither did he hesitate to take action, but he closely emulated Andronikos by destroying all opposition, contrary to Solomon's verse which says, "Better is it that thou shouldest not vow, than that thou shouldest vow and not pay.

When the sultan of Ikonion (this was still Kilij Arslan, in green old age and over seventy years old) heard of Andronikos's death and Isaakios's accession, he conjectured rightly that with such changes of emperors, dislocations would most likely occur, especially if a major war was being fought in the West. He now initiated an attack against the Thrakesian theme with picked cavalry and elite troops under the command of the amir Sames [autumn 1185]. Finding the region of Kelbianos emptied of men experienced in bearing arms (for they all had flowed like torrents towards Isaakios, who had just now donned the purple robe), he took many captives, seized all kinds of herds, and loaded his troops with other spoils.

With the Eastern nations pacified by additional lavish outlays, as well as by the payment of annual tribute (thus did those who sit over us Romans know how to free themselves of the foreigner, pursuing housekeeping cares like maidens of the bedchamber who toil at wool spinning), Isaakios decided to seek a wife from among the foreign nations, for the woman he had married earlier had died. After his envoys had made the negotiations, he took as his betrothed wife the daughter of Bela, the king of Hungary, who was not yet ten years old.

He celebrated the wedding rites penuriously [end of 1185 or beginning of 1186], using public monies freely collected from his own lands. Because of his niggardliness, he escaped notice as he gleaned other cities which were joined together around Anchialos, provoking the barbarians who lived in the vicinity of Mount Haimos, formerly called Mysians and now named Vlachs, to declare war against him and the Romans.

He celebrated the wedding rites penuriously [end of 1185 or beginning of 1186], using public monies freely collected from his own lands. Because of his niggardliness, he escaped notice as he gleaned other cities which were joined together around Anchialos, provoking the barbarians who lived in the vicinity of Mount Haimos, formerly called Mysians and now named Vlachs, to declare war against him and the Romans.

Made confident by the harshness of the terrain and emboldened by their fortresses, most of which are situated directly above sheer cliffs, the barbarians had boasted against the Romans in the past; now, finding pretext like that alleged on behalf of Patroklos - the rustling of their cattle and their own ill-treatment-they leaped with joy at rebellion.

Made confident by the harshness of the terrain and emboldened by their fortresses, most of which are situated directly above sheer cliffs, the barbarians had boasted against the Romans in the past; now, finding pretext like that alleged on behalf of Patroklos - the rustling of their cattle and their own ill-treatment-they leaped with joy at rebellion.

The instigators of this evil who incited the entire nation were a certain Peter and Asan, brothers sprung from the same parents. In order to justify their rebellion, they approached the emperor, encamped at Kypsella [early 1186, requesting that they be recruited in the Roman army and be awarded by imperial rescript a certain estate situated in the vicinity of Mount Haimos, which would provide them with a little revenue. Failing in their request-for the punitive action of God supersedes that of man-they grumbled because they had not been heard; and with their request made for naught, they spat out heated words, hinting at rebellion and the destruction they would wreak on their way home. Asan, the more insolent and savage of the two, was struck across the face and rebuked for his impudence at the command of John.

Thus did they return, unsuccessful in their mission and wantonly insulted. What words could possibly describe and embrace the endless string of Trojan woes inflicted on the Romans by these impious and abominable men? But none of this now; let us proceed with the narrative in historical sequence.

As Isaakios Komnenos still ruled as tyrant over Cyprus and was not disposed to keep his hands off the revenue payments that were promised to the emperor, or to bend his knee to him, or to moderate the horrors which he wickedly inflicted on the Cypriots, ever contriving novel torments, the emperor decided to fit out a fleet against him. Seventy long ships were made ready; the designated commanders were John Kontostephanos, who had arrived at the threshold of old age, and Alexios Komnenos, who, although of good stature, courageous, and a second cousin to the emperor, had had his eyes cut out by Andronikos and thus was considered as unfit for battle by all those participating in the cam- paign. His appointment was deemed by many as an inauspicious omen.

The voyage to Cyprus was without danger, with a very favorable wind gently filling the sails, but immediately after entering the harbors, a storm broke out that was more furious than any at sea. Isaakios, ruler over Cyprus, engaged them and put them to flight. The most formidable pirate on the high seas at that time, a man called Megareites, unexpectedly came to the aid of Isaakios and attacked the ships, which he found emptied of men, for they had disembarked to join in the land war. The captains of the triremes performed no brave deed but readily surrendered themselves into the hands of the enemy. Isaakios handed them over to Megareites to do with them as he wished. He took them to Sicily, where he recognized the tyrant of that island as his lord. Isaakios, after defeating the Romans, enlisted many in his own forces, and many he subjected to savage punishments, for he was an inexorable tormentor; among these was Basil Rentakenos, whose legs he cut off at the knees with an ax. This man was most skilled in warfare and had served as a teacher to Isaakios as Phoenix of old instructed Achilles to be a speaker of words and a doer of deeds. The most wrathful of men, Isaakios's anger ever bubbled like a boiling kettle; when in a rage, he spoke like a madman with his lower jaw aquiver, and not knowing how to reward his pedagogue with bright gifts, he subjected him to such retribution. He allowed the ship's crews to go wherever they wished, and they came to their homes as though return- ing after a long time from a distant shipwreck, as many, that is, as did not succumb to one of the three evils of sea, hunger, and death.

When the Vlachs were afflicted with the disease of open rebellion, the leaders of this evil being those I cited above,""' the emperor marched out against them [spring 1186].

These events, therefore, must not be overlooked and unrecorded. At first, the Vlachs were reluctant and turned away from the revolt urged upon them by Peter and Asan, looking askance at the magnitude of the undertaking. To overcome the timidity of their compatriots, the brothers built a house of prayer in the name of the Good Martyr Demetrios. In it they gathered many demoniacs of both races; with crossed and bloodshot eyes, hair dishevelled, and with precisely all the other symptoms demon- strated by those possessed by demons, they were instructed to say in their ravings that the God of the race of the Bulgars and Vlachs had consented to their freedom and assented that they should shake off after so long a time the yoke from their neck; and in support of this cause, Demetrios, the Martyr for Christ, would abandon the metropolis of Thessaloniki and his church there and the customary haunts of the Romans and come over to them to be their helper and assistant in their forthcoming task. These madmen would keep still for a short while and then, suddenly moved by the spirit, would rave like lunatics; they would start up and shout and shriek, as though inspired, that this was no time to sit still but to take weapons in hand and close with the Romans. Those seized in battle should not be taken captive or preserved alive but slaughtered, killed without mercy; neither should they release them for ransom nor yield to supplication, succumbing like women to genuflections. Rather, they should remain as hard as diamonds to every plea and put to death every captive.

These events, therefore, must not be overlooked and unrecorded. At first, the Vlachs were reluctant and turned away from the revolt urged upon them by Peter and Asan, looking askance at the magnitude of the undertaking. To overcome the timidity of their compatriots, the brothers built a house of prayer in the name of the Good Martyr Demetrios. In it they gathered many demoniacs of both races; with crossed and bloodshot eyes, hair dishevelled, and with precisely all the other symptoms demon- strated by those possessed by demons, they were instructed to say in their ravings that the God of the race of the Bulgars and Vlachs had consented to their freedom and assented that they should shake off after so long a time the yoke from their neck; and in support of this cause, Demetrios, the Martyr for Christ, would abandon the metropolis of Thessaloniki and his church there and the customary haunts of the Romans and come over to them to be their helper and assistant in their forthcoming task. These madmen would keep still for a short while and then, suddenly moved by the spirit, would rave like lunatics; they would start up and shout and shriek, as though inspired, that this was no time to sit still but to take weapons in hand and close with the Romans. Those seized in battle should not be taken captive or preserved alive but slaughtered, killed without mercy; neither should they release them for ransom nor yield to supplication, succumbing like women to genuflections. Rather, they should remain as hard as diamonds to every plea and put to death every captive.

With such soothsayers as these, the entire nation was won over, and everyone took up arms. Since their rebellion was immediately successful, all the more did they assume that God had approved of their freedom. Freely moving out a short distance without opposition, they extended their control over the lands outside of Zygon. Peter, Asan's brother, bound his head with a gold chaplet and fashioned scarlet buskins to put on his feet. An assault was made upon Pristhlava [Preslav] (this is an ancient city built of baked bricks and covering a very large area), but they realized that a seige would not be without danger, and so they bypassed it. They descended Mount Haimos, fell unexpectedly upon the Roman towns, and carried away many free Romans, much cattle and draft ani- mals, and sheep and goats in no small number.

The emperor marched out against them, and they, in turn, occupying the rough ground and inaccessible places, stood their ground for a long time. But unexpectedly a blackness rose up [solar eclipse, 21 April 1186] and covered the mountains which were guarded by the barbarians, who had laid ambuscades at the narrow defiles; the Romans, undetected, came upon them unawares to send them scurrying in panic. The originators of this evil and commanders of the army, that is, Peter and Asan, and their fellow rebels ran violently to the Istros like the herd of swine in the Gospels who ran into the sea and sailed across to join forces with their neighbors, the Cumans. The emperor was hindered by the vast wilderness from making his way through Mysia. Many of the cities there are in the vicinity of Mount Haimos, and the majority or practically all, in fact, are built on sheer cliffs and cloud-capped peaks. Thus, he posted garrisons and did nothing more than set fire to the crops gathered in heaps. Subjected to the trickeries of the Vlachs, who observed him closely, he turned back forthwith, leaving matters there to continue in turmoil [probably July 1186]. As a result, he encouraged the barbarians to sneer even more broadly at the Romans and emboldened them all the more.

On arriving at the queen of cities, Isaakios plumed himself on his achievements, so much so that one of the judges (this was Leon Monasteriotes) said that the soul of Basil the Bulgar-Slayer [Basil II, 976-1025] was aggrieved because the emperor had utterly cast aside his Typikon and all the writings he had lodged in the Monastery of Sosthenion,among which he had prophesied the revolution of the Vlachs. Isaakios continued apace, deriding and ridiculing the prediction as being apparently mistaken, contending that he had won over the rebels by persuasion and had instantly led them back to their former subordination and bondage, while it took Basil a very long time to do so, and that Basil had belched forth empty lies and vain prophecies as from the bayeating throat and tripod.

On arriving at the queen of cities, Isaakios plumed himself on his achievements, so much so that one of the judges (this was Leon Monasteriotes) said that the soul of Basil the Bulgar-Slayer [Basil II, 976-1025] was aggrieved because the emperor had utterly cast aside his Typikon and all the writings he had lodged in the Monastery of Sosthenion,among which he had prophesied the revolution of the Vlachs. Isaakios continued apace, deriding and ridiculing the prediction as being apparently mistaken, contending that he had won over the rebels by persuasion and had instantly led them back to their former subordination and bondage, while it took Basil a very long time to do so, and that Basil had belched forth empty lies and vain prophecies as from the bayeating throat and tripod.

Asan and his barbarians crossed the Istros and met the Cumans, from among whom he enlisted a large number of auxiliaries. Then, as was their intention, they returned to their country of Mysia [after summer 1186]. Finding the land swept clean and emptied of Roman troops, they marched in with even greater braggadocio, leading their Cuman auxiliaries as though they were legions of spirits.l0ss They were not content merely to preserve their own possessions and to assume control of the government of Mysia; they also were compelled to wreak havoc against the Roman territories and unite the political power of Mysia and Bulgaria into one empire as of old.

The former triumphs would have been repeated had the emperor himself set out once more against the rebels. But he deferred his own attack until another time and handed over the command to his paternal uncle, the sebastokrator John. Without exposing his troops to danger, John commanded them in a most laudable manner and annoyed the enemy with constant attacks whenever they formed in close order to give battle and descended into plains fit for driving horses. Shortly afterwards, he was divested of his command for setting his eyes on the throne.

The kaisar, John Kantakouzenos, the emperor's brother-in-law who was married to his sister, succeeded to the command of the sebastokrator.

The man was huge in size and most courageous of heart, and with a booming voice. Although greatly experienced in the art of warfare, he was unsuccessful most of the time, or, rather, all of the time, because of his rashness and arrogance. The light of his eyes had been extinguished by Andronikos, who had heated for him the iron that maims. The bar- barians had learned from their recent defeat that to leave the mountains and turn off into the plains was inimical to them. The kaisar, mistaking the guardedness of their behavior for cowardice, tracked them down in the manner of huntsmen as he advanced and then set up camp wherever he happened to be at the time without fortifying it with trenches. When the enemy attacked in the night, he barely saved himself, and his troops were sorely afflicted in diverse ways. Those who were caught as they slept were killed, and those who did not have time to strap on their weapons were taken captive; those who were able to escape without their weapons collected around the kaisar, only to find him to be more vindictive than the enemy. He ceaselessly insulted and reproached them for being helpless and for utterly betraying him. In an attempt to retrieve the defeat, he donned his armor, leaped on his spirited Arabian stallion, and couched his strong, heavy lance. Pointing his weapon in the direction of the enemy, he exhorted the survivors of his army to follow him, even though he could not see the enemy and had no idea where they were encamped. When the Romans had been put to flight by the barbarians, their standards were captured and the soft tunics and elegant cloaks of the kaisar snatched and put on by the companions of Asan and Peter. The victors, with the standards at their head, once more occupied the plains.

When Kantakouzenos laid aside his command, Alexios Branas was proclaimed general; he was short in stature, but gigantic in the scope of his intelligence and the cunningness of his designs, and he was the most versed in generalship of all men at that time. Taking over the command of the army, he executed his responsibilities as general with caution, not rashly, always advancing step by step, careful to harass the enemy while taking just as much care to keep his own troops out of danger. After traversing much rough terrain, he bivouacked in the vicinity of the so- called Black Mountain and established an entrenched camp. By anticipating any attack, he performed a very great service.

Branas was obsessed by a burning passion for the throne; he held Emperor Isaakios in contempt or, rather, unable to bear seeing him reign, he had before [end of 1185] been detected aiming at the throne when he was general of the troops in the war against the Sicilians. Aware that it would be difficult to gain the support of the Roman forces under

his command in fomenting the rebellion for which he painfully longed, he first won over his German allies; but because he later deemed that they would be insufficient help in any future attempt to seize the throne, he decided to follow the same course taken by Isaakios when he traveled without difficulty the road to autocracy. By night he entered the Great Church and proceeded into the sanctuary in order to address those standing without; he entreated those who come inside to come to his aid, to help him avert the emperor's unjust design, asserting that he had never given offense in any manner whatsoever. He supplemented this with a tiresome narration of the great victories he had won, how he had twice attacked the enemy forces and had, as many times, turned them to flight in great battles and by way of excellent stratagems. Again he fostered the same passion, forcibly restraining and bridling his lust for power as though it were an uncontrollable horse; but this time [c. April 1187], luckily receiving the support of the troops, he was prompted to bring his earlier objectives to a successful conclusion.

His kinsmen consulted, those who were also his fellow countrymen (for they were from Adrianople), many in number and all of them powerful, he put on the red buskins. Next, he went to his native city, where he was proclaimed emperor by all the troops, and then set out for the imperial city and encamped in the Outer Philopation, as it was called.

He approached the City's walls late in the afternoon with his well armed forces, astride a horse all black but for white horsehairs growing around the brow in a crescent shape, and threatened and exhorted both the imperial troops defending the walls and the City's residents who were spectators of the goings-on. He promised to reward those who sympathized with his cause, and if they should open wide the gates and admit him inside, they would find him to be both savior and benefactor, embracing them with open arms; but if, when entering by the door, as he did not wish to climb up some other way, he should be opposed and resisted, and if he should be forced, at all hazards, to steal his way inside and to snatch the throne, he would with just cause do to them what savage beasts do when they enter the sheepfold by some way other than the door. Having boasted in such fashion with his troops arrayed to demonstrate his battle readiness, he returned to his camp.

On the following day, when the sun's light began to illumine the eastern skies, he came to the City's walls once again, at the land gates, called the Gates of Charsios, where he deployed his army into right and left wings. Taking up his position in the center of the phalanx, he ordered his men to engage the troops that poured out of the City. The emperor did not deploy all his troops within the City's gates to fight mightily on his behalf but commanded one part to stand on the walls above while another part sallied out to the farthest point of the fosse, where it was to oppose the enemy as best it could. Should the troops become exhausted by the heavy press of the enemy, he urged them to stay close to the walls so that those manning the battlements could defend them from above. Until high noon both sides engaged in the discharge of missiles and in skirmishes. For a short time Branas's troops prevailed over those of the emperor, as they were seasoned soldiers, especially those who constituted the Latin infantry. Survivors were searched out from among the captured Sicilian troops, and the emperor set them free from their bonds and prison, placed them under arms, and sent them against Branas. Branas's infantrymen formed a mighty phalanx around him, and they were fenced about with a cavalryman's shield, a long sword and a pointed lance. Supported by their cavalry, they utterly routed the troops from the City, and these were compelled to cross the fosse and cling to the walls; the troops who stood on the walls came to their aid.

Thus ended the events of that day. After suspending hostilities for five days, the tyrant once again massed his forces for battle and came before the walls of the City. Making himself appear terrifying to the citizens in an attempt to incite those within to revolt, he detached a division of his troops and dispatched them to the northern side of the City, opposite the strait called the Ford of the Ox, from which the waterway can clearly be seen making its serpentine way to the palace in Blachernai, as can all the sections of the City facing north. In compliance with their orders, they ascended the high ground of the hills in that region and raised their standards. As the sun's rays fell on the armor and the newly burnished and smooth corselets'°89 they were reflected like flashes of lightning, so that the City's populace gathered in groups on the hilltops of the City to view the scene with great amazement.

After this, they won over to their side the inhabitants of the Propontis, who, though not all skilled in warfare, were each and every one adept in pulling an oar. The boats they had built for the catching of fish they converted into warships, covering the sides with thick planks; some were equipped with slings, while others took on board bows and quivers. Thus transformed from weavers of nets into fierce warriors, they triumphed over, and prevailed against, the imperial triremes which, while compassing the City, were on the lookout for nocturnal assaults by Branas's troops and diligently kept watch lest the tyrant, despairing of entering through the land gates, slip inside unnoticed through the seaside gates. At first, those on the long ships thought that the fishermen were utterly insane and were confident that as soon as they moved against the fishing boats they would dash them. When the time came to exchange blows, the triremes sailed forth as the crooked and straight war trumpets sounded. The ferryboats moved out in silence; the men on board, breathing fury, smote the sea with their oars and engaged the huge ships of the enemy, over whom they prevailed, and hemmed them in along the shore of the City. Because of their great length and slowness in turning, the triremes could not at once inflict damage on the adversary. As the fishing boats moved forward en masse, many would- randomly surround a single trireme; attacking stern and prow and both sides, they won a resounding victory and raised a splendid trophy.

Unable to bear the disgrace of the defeat for long, the commanders of the emperor's fleet prepared to give pursuit to the fishing boats. They would have quickly destroyed the ferry boats with liquid fire1092 had not Branas's heavy-armed troops descended from the crest of the hill to the shore and come to their assistance.

The rebel, who saw that he could neither steal his way into the City nor achieve his plans through warfare or persuasion, contrived another scheme. He could either force the queen of cities to submit in the face of famine, setting up against her the mightiest and most powerful siege engine of all-starvation (for the eastern and western parts of the Roman empire had already gone over to him), forbidding any supply ship to put into Byzantion, or he could attack with a larger and more vigorous fleet. These things would have unfolded according to plan had not the Divinity refused to consent to their realization. The emperor saw that the City's entire populace was devoted to him, that not only would they not tolerate that Branas should reign as emperor but that they also subjected him to curses. He carried up to the top of the walls, as an impregnable fortress and unassailable palisade, the icon of the Mother of God taken from the Monastery of the Hodegoi where it had been assigned, and therefore called Hodegetria, and took courage to fight back on his own, deeming the long confinement inside the City to be detrimental, creating an abominable situation; also, he yielded to the rebukes of the kaisar Conrad.

This Conrad was an Italian by race; his father ruled over Montferrat. He so excelled in bravery and sagacity that he was far-famed, not only among the Romans but also celebrated among his countrymen, and Emperor Manuel was especially fond of him as one graced with good fortune, acute intelligence, and strength of arm. It was he who, having received bounteous gifts from Emperor Manuel, was induced to raise his hand against the king of Germany, and defeated in battle the bishop of Mainz [Christian], the king's chancellor, who had invaded Italy with a huge force. He had seized him, put him in chains, and stiffly maintained that he would not release him unless the emperor of the Romans commanded him to do so.

At the time when Emperor Isaakios had dispatched an embassy to Conrad's brother Boniface to propose a marriage contract between him and his sister Theodora, Boniface had recently taken a bride and was celebrating the hymeneal rites. Now, Conrad had lost his consort in life to Death. The envoys deemed this a godsend and their second choice far superior to their first. They assuaged Conrad with grand promises, and he accompanied them on their return [after 22 March 1187. The emperor gave the marriage feast and shortly afterwards Branas's rebellion ensued. Conrad continuously bolstered the emperor's spirits, which were dampened and ignobly languishing, and by inspiring the highest hopes, he served as a whetstone honing a fine edge to the emperor's resolution to give battle.

The emperor gathered together those of the monks who go barefoot and couch on the ground and brought down those who live on pillars, sus- pended above the earth; but while he prayed through them to God to bring an end to the civil war and not to allow the sovereignty to pass over, or to fly off, to another, he himself neglected to make preparations for battle, resting all his hopes on the panoply of the Spirit. Conrad, on the other hand, acting as the crab to the mussel, would often awaken him from sleep and prod him to rise up, persuading him not to rest all his hopes in these mendicants. He counseled the emperor to attend to the troops, to employ the heavy infantry against the rebel, that is, not only the arms on the right hand, which is the assistance of holy men, but also that on the left, which is the armor strengthened by sword and breastplate. He admonished him, moreover, not to be sparing of money but to spend it freely to raise troops because, with the exception of the emperor's blood relations and those whose residences were in the City, everyone else had submitted to Branas, and it was not possible to bring in a military force from the outside.

Prodded continually by the kaisar's words as though by an ox-goad, the emperor woke from his torpor, threw off his apathy, and began to collect an auxiliary force. Contending that he did not have an abundance of gold coins, he removed the silver vessels from the imperial treasuries and deposited them as security in the monasteries, which abounded in gold. The monies he obtained from this source he distributed for the raising of an armed force. (After the victory, however, he did not restore the gold and even removed the deposited vessels.) In a short time, Conrad gathered from among the Latins in the City some two hundred and fifty knights, all fierce warriors, and five hundred foot soldiers. Not a few Ismaelites [Turks] and Iberians [Georgians] from the East who had journeyed to the queen of cities for trade purposes were also enlisted. The nobles loyal to the emperor, together with those in attendance at the imperial court, numbered about one thousand men. Such was the zeal that Conrad demonstrated on behalf of the emperor that he was deemed by all a blessing sent by God to the emperor in time of need.

Prodded continually by the kaisar's words as though by an ox-goad, the emperor woke from his torpor, threw off his apathy, and began to collect an auxiliary force. Contending that he did not have an abundance of gold coins, he removed the silver vessels from the imperial treasuries and deposited them as security in the monasteries, which abounded in gold. The monies he obtained from this source he distributed for the raising of an armed force. (After the victory, however, he did not restore the gold and even removed the deposited vessels.) In a short time, Conrad gathered from among the Latins in the City some two hundred and fifty knights, all fierce warriors, and five hundred foot soldiers. Not a few Ismaelites [Turks] and Iberians [Georgians] from the East who had journeyed to the queen of cities for trade purposes were also enlisted. The nobles loyal to the emperor, together with those in attendance at the imperial court, numbered about one thousand men. Such was the zeal that Conrad demonstrated on behalf of the emperor that he was deemed by all a blessing sent by God to the emperor in time of need.

Once, when he came upon the emperor while eating, he uttered a low moan and said, "Would that you showed the same eagerness in attending to the present conflict as you do to running to banquets, falling with gluttonous appetite on the foods set forth, and wasting all your efforts on emptying out dishes of carved meat." Isaakios blushed at these words and turned a bright red; he gave a forced smile, and taking hold of the kaisar's mantle he remarked agitatedly, "Ho there! At the proper time we shall both eat and fight."

At this time, the following omens made their appearance in the sky: stars showed forth in the daytime, the air was turbulent, certain phenomena called halos appeared around the sun, and the light it cast was no longer bright and luminous but pale [4 September 1187].

Such being the state of events, the emperor assembled his troops and decided that he should no longer remain withdrawn, sitting within doors, but that he, too, should show himself before the rebel with sword drawn. Putting on his coat of mail, he stood within the wall of the City which Emperor Manuel had raised to protect the palace in Blachernai and emboldened his kinsmen and the soldiery standing nearby, exhorting them as follows.

"Certainly it is better and irreproachable in the sight of God that the lawful ruler, even before his subjects, should brave the first danger rather than yield to a revolutionary who foments civil war among those who speak the same tongue. Should there be some among you who are uncertain and undecided in your minds or, on the other hand, are fervidly and passionately devoted to him, or again who yesterday served him slavishly as master but today despise him, I make of you a most reasonable request: remain at home, offering assistance to neither side until the issue is resolved by battle and then submit with the others to the victor, or else leave the City and go over to the rebel before the conflict begins; fight for him and bear the brunt of battle, so that he shall owe you a greater debt of gratitude should he gain the trophies of victory. As for those of you who cleave to me and honor me with your lips""' but are inclined to another in your hearts and render to him all your good-will, I know not whether you shall be praised or weighed in the balance by God, who, loving justice, examines the intents of the heart. I refuse to think of that which is even worse and most shameless, that is, to desert to the tyrant in the midst of battle, thus setting a bad example even for the best of men to change sides and go over to the enemy, as we observe with birds flying in flocks: when one flies away, all the others fly off with it with a rushing sound, and when another comes to rest, the entire flock follows suit. "

He spoke in this manner because he distrusted his paternal uncle, the sebastokrator John, who was an old friend of Branas and whose son celebrated his marriage to Branas's daughter shortly before the rebellion. All those who comprised the assembly were greatly aggrieved by these words. The sebastokrator, wishing to remove all suspicion from himself, placed all the members of his household and himself under the most dreadful curses if he had ever considered joining forces with Branas; neither was he so ignorant of his duty nor had he taken leave of his senses because of old age and become so complete a fool that he would replace as emperor his brother's son, who had raised from glory to glory the rustic and stranger, with a son-in-law about whose good intentions and actions concerning himself he knew absolutely nothing.

When the time came to give battle, the rebel gave the command for his forces to be drawn out in battle order; the gates of the City were thrown open, and the troops poured forth. The left wing was under the command of Manuel Kamytzes, who had supplied the emperor with no small sum of money when the mercenary forces were recruited. He was Branas's worst enemy, and realizing what evil would befall him should Branas prevail, he revealed all his substance to the emperor and allowed him to take as much as he wanted, for he deemed it better to part with all his possessions on behalf of an emperor who was his friend and kinsman, and to receive in return much more gratitude should he emerge victorious, than to have his properties fill the coffers of a stranger, implacable and hard-hearted in his hostility, to his own derision and the former's great amusement. Emperor Isaakios himself commanded the right wing, composed of the best and most distinguished men-at-arms; the kaisar Conrad brought up the center with the assembled Latin cavalry and infantry.

The foremost place at the center of the opposing army's battle line, where were massed Branas's kinsmen, close friends, and those nobles of good courage who accompanied him, was held by Branas; the divisions deployed on either side were led by accomplished commanders and the Cuman Elpoumes.

It was not yet high noon when missiles were discharged, the two armies charged, and the infantry forces advanced and engaged in pitched battle. When the sun was ablaze in the zenith and the signal for battle was given, Conrad, with his purple-dyed emblem imprinted on his

and his troops' arms, was first to move. He fought then without a shield, and in lieu of a coat of mail he wore a woven linen fabric that had been steeped in a strong brine of wine and folded many times. So hard and compact had it become from the salt and wine that it was impervious to all missiles; the folds of the woven stuff numbered more than eighteen. When there was but a short distance between the two armies, he came to a stop; the foot soldiers arrayed themselves in the fashion of a wall and raised their javelins to give battle (buckler pressed on buckler, helm on helm,1102 and shield clashed against shield); the horsemen couched their lances and spurred on their horses with the em- peror's division close behind. Branas's troops could sustain neither the first shock of Conrad's heavy armed infantry nor the violent charge of the horse, and turning their backs, they scattered. Terrified on seeing this, the remaining divisions fled.

Branas shouted at the top of his voice, "Stand your ground, 0 Romans. We outnumber the enemy, and I myself shall be the first to engage them in combat." But though he pressed forward, he was unable to persuade anyone to turn around. He aimed his lance at Conrad, who was fighting without helmet, but he failed to deliver a mortal blow, harmlessly grazing Conrad's shoulder. In vain the weapon slipped from his hands; Conrad, holding his own lance with both hands, thrust it into Branas's cheekpiece, dazing him and throwing him headlong from his horse. Conrad's boydguards surrounded him and ran him through with their lances. They say that when Branas was first wounded by Conrad, he was terrified of death and so pleaded to be spared. Conrad replied that he must not be afraid; he assured him that nothing more unpleasant would happen than that his head should be cut off, and forthwith it was done.

Branas shouted at the top of his voice, "Stand your ground, 0 Romans. We outnumber the enemy, and I myself shall be the first to engage them in combat." But though he pressed forward, he was unable to persuade anyone to turn around. He aimed his lance at Conrad, who was fighting without helmet, but he failed to deliver a mortal blow, harmlessly grazing Conrad's shoulder. In vain the weapon slipped from his hands; Conrad, holding his own lance with both hands, thrust it into Branas's cheekpiece, dazing him and throwing him headlong from his horse. Conrad's boydguards surrounded him and ran him through with their lances. They say that when Branas was first wounded by Conrad, he was terrified of death and so pleaded to be spared. Conrad replied that he must not be afraid; he assured him that nothing more unpleasant would happen than that his head should be cut off, and forthwith it was done.

Because the flight was disorderly, everyone could slay the man he pursued. This happened only at the beginning of the rout, but was not continued thereafter. The Romans spared the blood of their fellow countrymen, and the pursued ran for their lives as fast as they could and escaped. The entrenched camp was plundered by the victors and exposed to looting, not only by the emperor's troops but also by the citizens who poured out of the City.

In this battle, Constantine Stethatos was also slain, pierced in the groin by a lance. He was a good and gentle man who, as governor of the province of Anchialos, was forced to follow Branas against his will, but despite Branas's hopes he was of no benefit to him. He did not save Branas and himself from falling to the sword even though he was the most celebrated astrologer of that time; evidently he had an inkling of something coming which convinced him to remain quietly in his tent, and he was not anxious about the enemy's attack. It is said that, on the basis of the signs of his art, he prophesied to Branas that on that day he would enter the City and celebrate a glorious triumph. Whether Stethatos actually said this, I have no way of knowing for certain, for not all things related by Rumor are devoid of deceit because Rumor loves a good story. If we give credence to the rumor, then the predictions of the prophet Stethatos would seem to have miscarried; on the other hand, a certain devotee of the astrologer's science contended that he was not at all mis- taken and had not failed in his art, for he associated the forecasts with Branas's head and one of his feet, which on that day were transfixed on pikes and paraded through the agora, together with the head of a certain baseborn fellow by the name of Poietes [Poet] which no warrior's hand had taken from him. The emperor, after that brilliant victory and defeat of the enemy, commanded that it. be cut off, to what end and purpose I know not.

Thus ended the conflict of that time. The emperor gave himself over to feasting, with the palace gates leading into the court as well as the outer windows opened wide so that all those who wished to do so could come inside and get a glimpse of the triumphant emperor. As he greedily attacked the bread and laid violent hands on the meats, for the purpose of diversion and after-dinner sport, he ordered Branas's head brought forward. Carried inside and thrown on the floor, the grinning head with eyes closed was tossed back and forth like a ball. Later it was taken to his wife, who was confined within the palace, and she was asked if she knew whose head it was. Fastening her eyes on this pitiable shocking sight, she replied, "I know and my heart bleeds." She was prudent and much esteemed for her ability to hold her tongue, which is so becoming to women and for which her maternal uncle, Emperor Manuel, called her virtuous among women and the flower of his family.

As soon as those who were positioned behind the front ranks during the conflict realized that a rout was taking place, they scattered in flight, and thinking that those who followed were the enemy, they rode on all the harder to avoid capture. Those who followed vied with those who preceded them in the impetuosity of their flight to save themselves. Alarmed at being pursued by the enemy, they prayed openly that their horses' hooves might not strike the ground, thus enabling them to fly like Pegasos, and that they themselves might become invisible as though wearing the helmet of Hades. In truth, so great was their terror that they were willing to do and pray for anything. The majority would have slipped and fallen to their death at the bridge which leads to Daphnoution had not someone prevailed upon them to check their headlong flight in good order and to proceed through the archway with utmost caution. This the man accomplished by lifting his hands towards heaven and swearing by the Divinity that none of the enemy was chasing after them but rather had turned around and given up pursuit.

Those who were lowborn and of humble station returned to their homes without harassment or reproach. They found their dwellings, which lay in an obscure part of the City, preserved from harm and had no fear of anyone coming after to punish them. On the other hand, those who were of illustrious station and had distinguished themselves as gover- nors and magistrates assembled in a body and sent a legation to the emperor, petitioning him to forgive them for their act of sedition in following the rebel; in return for a pardon from the emperor, they swore to remain virtuous and loyal servants in the future, and by their deeds to prove their repentance for having taken up arms against their lord and emperor and for having done violence against him out of sheer madness. Should the emperor, they said, in fueling the immutable passion within his soul, refuse to swallow his wrath for one day,""' or should he here after hold their sins against them, fanning the smoldering rancor into sparks of rage, they should flee from before the emperor""' and seek a distant lodge""' among the barbarian nations which despise the Romans. There they would do for the Romans what they are bound to do for those who come streaming into them, for it is not at all novel that one should seek out his enemy and flatter him, finding his adversary to be his friend.

These things did the envoys murmur. The emperor granted amnesty to all, and admitting into his good graces those who approached him as suppliants, he urged them to prove their repentance for having transgressed their sworn oaths to him by appearing before the great high priest [patriarch] to obtain from him the absolution of the anathema which the City's inhabitants had called down upon them when they stood atop the battlements as spectators of the actions below. And many who were God-fearing men appeared before the patriarch; the others nodded their heads in assent at the conclusion of the exhortation but deemed entering the Great Church and making public confession utter nonsense. I will omit describing how the insolent among these, after leaving their audience with the emperor, mocked and ridiculed him, saying that it was nothing new for one who had been destined for the priesthood-for he was also accused of this-now to instruct them to do what he had been taught from adolescence. Many went over to Asan and Peter; but they returned shortly afterwards when they received imperial letters.

At this time a most unexpected event took place. The emperor actually granted permission to citizens and foreigners alike to pour forth and maltreat the peasants living near the City, as well as those who dwelled along the Propontis, for having gone over to Branas. On the night of the very day that Branas was defeated, liquid fire was hurled against the houses of the unhappy inhabitants of the Propontis; contained in tightly covered vessels, the compound would ignite suddenly and, like bolts of lightning striking intermittently, consume whatever it happened to fall upon. The blazing fire burned and destroyed every building, whether it was a holy temple, holy monastery, or private dwelling. Because the disaster was wholly unexpected and the conflagration spread, consuming not only the buildings, with the flames very nearly covering the sky, but also men's possessions, no one could rescue anything except the monies one could carry away in his arms.

At dawn on the following day as though by invitation, the Latin troops under the command of the kaisar Conrad marched out, and the multitude of commoners and beggars of the City and her environs came running, some still bearing arms while others carried whatever weapons were at hand. What did they not seize? What evil did they not perpetrate? They razed buildings, carried off the riches inside, searched through the holy monasteries, removed sacred furniture, desecrated holy vessels, showed no reverence for the venerable gray hair of the monks, disregarded virtue which even the enemy knew how to honor, and, to make a long story short, they ill-treated those they attacked in every way. Many who grumbled because their homes had been stripped were punished with death. These horrors would have continued on and with increased intensity had not certain men reported to the emperor; having suffered grievously themselves, they naturally urged him to correct the situation. The emperor dispatched forthwith men of high rank and noble birth to check the riotous mob attacks, and at long last the extensive destruction was brought to an end.""'

But even these words are inadequate as a lament for those whose hearts are compassionate and for whom the tears well up in hot streams at the misfortunes of the suffering. The artisans of the City did not consent to the villanies of which I have given an account, holding them to be horrendous, for the Latins not only were free of speech and plumed

themselves on having defeated Branas but they had also inflicted intolerable sufferings on their Roman neighbors outside the City. In bands and companies they burst in upon the houses of the Latin nations like a rushing torrent. Unintelligible cries rent the air, louder than the din raised by flocks. of jackdaws, cranes, and starlings as they spread their wings for flight,"" or the hunter's halloo and whoop; the victims ap- pealed to one another as they were being dragged by their tunics, but there was no one there to heed those who proposed conditions of peace; ears stopped, as are those of asps, they ignored every wise sorcerer. Irrational anger held sway over the vulgar mob at that time, even as it was emboldened by love of the foreigners' money. They believed that they would expel the Latins from their dwellings with little trouble and with impunity seize whatever treasure was stored within as they had done during the reign of Andronikos. But their hopes were turned topsy-turvy. When the adversary saw the rabble rushing towards them, they barricaded with huge pickets all the streets leading in their direction, and putting on their coats of mail, they took up their stand in close array at the fortifications. The vulgar mob rushed headlong in many attempts to scale the barricades, but they failed in their purpose and were badly mauled by the Latins; drunk with wine and fighting without armor or arms against armed men, the majority soon learned of their folly and discovered that Epimetheus is inferior to Prometheus' when, smitten by arrows or wounded by spear thrusts at close quarters, they fell to the earth.

Thus did this horror prevail from the afternoon of that day until late evening; at break of day, the Romans, most of whom were armed with weapons, with a great rush assembled to give battle a second time. But certain notables from the emperor arrived to restrain them, while certain representatives of the Latin race outwitted the simple-minded and quelled their excessive impetuosity. The Romans who had lost their lives in the fray were collected; their garments were first removed and their hair clipped short, and their corpses were laid in their court, displayed before the emperor's agents. Feigning sorrow over the loss of their own countrymen, the Latins pleaded that a second battle not be allowed to begin, that they not suffer twice the losses to which they now bore witness. The emperor's agents conveyed these sentiments to the army of artisans, per- suading them to look upon the dead and contending that they should not applaud what had taken place, and they finally succeeded in appeasing the rabble and prevailed on them to return each to his own work. In other words, had they not been armed by their intimate friend and leader-I mean captain wine-or to be more precise, had he sharpened their sword for battle, they would not have dispersed so readily and without argument, obedient to the exhortation of the great men who served as mediators. Had they not been drunk with wine from before- indeed, they were heavier with wine than are wine kegs-what spell or melodies hummed by the Sirens could have lured them toward peace or disposed them to some other noble action? They were continuously mocked for their drunkenness. Menander censures them as follows: "Byzantion makes drunks of its merchants; they drank all night long.""" To this point, then, have events borne us.

BOOK TWO

Smitten now by misgivings, the emperor launched a second attack against the Vlachs because he had mismanaged affairs in the enemy's country during his first inroad, when he had risen up and left as though he had been attacked by the enemy without having installed Roman garrisons in the fortresses or taken any valuable barbarian hostages. He marched out of the City with a few of his comrades in war [September 1187] with the rest of the army assembled by command. He had heard that the Vlachs were no longer hiding out in the mountains and hills. Having enlisted Cuman mercenary troops, they had penetrated into the regions of Agathopolis, utterly despoiling the land and wreaking havoc. Before the desperate and violent onslaught of the barbarians, he em- ployed the following tactic: he thought he would force the enemy to cower in fear and his own troops not to faint during the impending second assault on the Vlachs if he himself were the first to take up arms and mount his war-charger.

At Taurokomos (a small estate with inhabited villages, situated not very far from Adrianople) he waited for his forces to assemble and commanded the kaisar Conrad not to delay his departure.""

Conrad was openly displeased that the emperor showed him favors he considered unbefitting his family status and not harmonious with his im- perial marital connection and was unhappy that all his proud hopes resulted only in his wearing the buskins of uniform color"" that are given but to a few (I speak of the insignia of the kaisars). Long ago he had taken up the cross at home with the intention of traveling to Palestine, which was now in the hands of the Saracens of Egypt."" On the way he had celebrated his marriage to the emperor's sister. But he agreed to march out with the emperor and help prepare for the impending campaign so that, God willing, he might prevent the Romans from suffering further misfortunes at the hands of the Vlachs. However, he then changed his mind.

With a sturdy and newly reconditioned ship, he set sail for Palestine and came to anchor at Tyre [14 July 1187], where he was hospitably received by his countrymen, who regarded him as some higher power. He fought against the Saracens and recovered Joppa, now called Ake [Acre; 12 July 11911,"'9 as well as other cities for his compatriots. But it was ordained that they should suffer evil fortune in those parts: many excellent and brave generals who had voluntarily undertaken the journey at their own expense, for Christ's sake, were lost, and Conrad himself, who had won the admiration of the Agarenes for his bravery and prudence, survived but a short time before he was slain by an Assassin [28 April 1192]. 1120

The Assassins are a sect who are said to hold such reverence for their chief in carrying out his commands that he has only to make a sign with his brows for them to hurl themselves over cliffs, or to dance over swords, or to leap into water, or to cast themselves into fire. Those in authority over the Assassins send them to kill the victims they have chosen. Approaching their victims as friends, or asserting that they had some urgent business with them, or pretending that they had come as envoys of nations, they would strike many times with their dirks and kill them as adversaries of their lord without considering the difficulty of the deed or the possibility that they themselves might be killed before they were able to inflict death on another.

The emperor set apart about two thousand select troops which he provided with arms and swift-footed mounts and marched out from Tau- rokomos towards the enemy; the baggage and camp attendants he ordered to move on to Adrianople. The scouts reported that the lands around Lardeas had been overrun by the enemy, who had killed large numbers and had taken many captives and were observed returning loaded down with much booty.

Sounding the war trumpet at night, the emperor mounted his horse and marched out, to arrive [7 October 1187] at a place called Basternai, where he rested his troops while the enemy failed to show themselves.

Rising early for departure from Basternai after three days [11 October 1187], he took the road leading straight to Beroe. He had not quite gone four parasangs'121 when a well-equipped soldier appeared with bad news written on his face. Gasping frequently for breath, he announced that somewhere in the vicinity the enemy was returning with captives, easily making their way on all fronts since they had not met any opposition, and that they were heavy-laden with spoils. Immediately dividing his troops among his commanders and drawing them up into battle formation, he took the road which the adversary was reported traveling.