The Empresses of Constantinople - Author: Joseph McCabe

Michael now returned to the problem of John, and, when he remarked to his courtiers that it was absurd to have “two heads under one hat,” they knew that the youth was doomed. We have no reason to doubt the statement of the chronicler that Eulogia supported him in this design, but we may at least assume that the manner of executing it was due to Michael alone. He ordered that the harmless and helpless young man should be blinded. A long experience had made the Greeks ingenious in this operation, and, instead of removing the eyes with knives, or using hot irons, they now sometimes blinded a man by an elaborate concentration of intense light on the retina or by the use of boiling vinegar. The more humane method of blinding by an intense light was used in the case of John, and the unfortunate youth was then incarcerated for life in a fortress on the coast of Bithynia.

This ghastly operation was performed on the day on which the churches and monasteries of the Byzantine Empire offered their clouds of incense in honour of the birth of Christ. It is at least gratifying to find that it did not pass without protest. A warm-hearted youth attached to the Court lost his nose and lips for speaking too freely about it, and many others had to be punished.

Theodora seems to have been a silent, perhaps disgusted, witness of her husband’s course, and there is some faint evidence that Michael’s elder sister dissented from it. In fact, the patriarch Arsenius himself openly resented this flagrant violation of a thrice-repeated oath, and thus led to a long and fierce ecclesiastical struggle in which the two royal nuns were actively engaged. The patriarch’s procedure was not as emphatic and thorough as it ought to have been, but he at least distinguished270 himself among the crowd of corrupt and servile bishops and abbots by more or less excommunicating Michael. A council of bishops then obliged the Emperor by deposing Arsenius and putting a more courtly prelate in his place, but the hostility and derision of the people soon induced Germanus to retire, and a clerical diplomatist named Joseph occupied the see. As the furious schism of the Arsenians and the Josephites, which followed, will cross the lines of our story for some time to come, it is necessary to introduce this fragment of ecclesiastical history. For the moment it is enough to say that in 1268 the patriarch Joseph absolved from his sin the ostentatiously penitent Emperor, before a crowd of weeping Senators and priests.

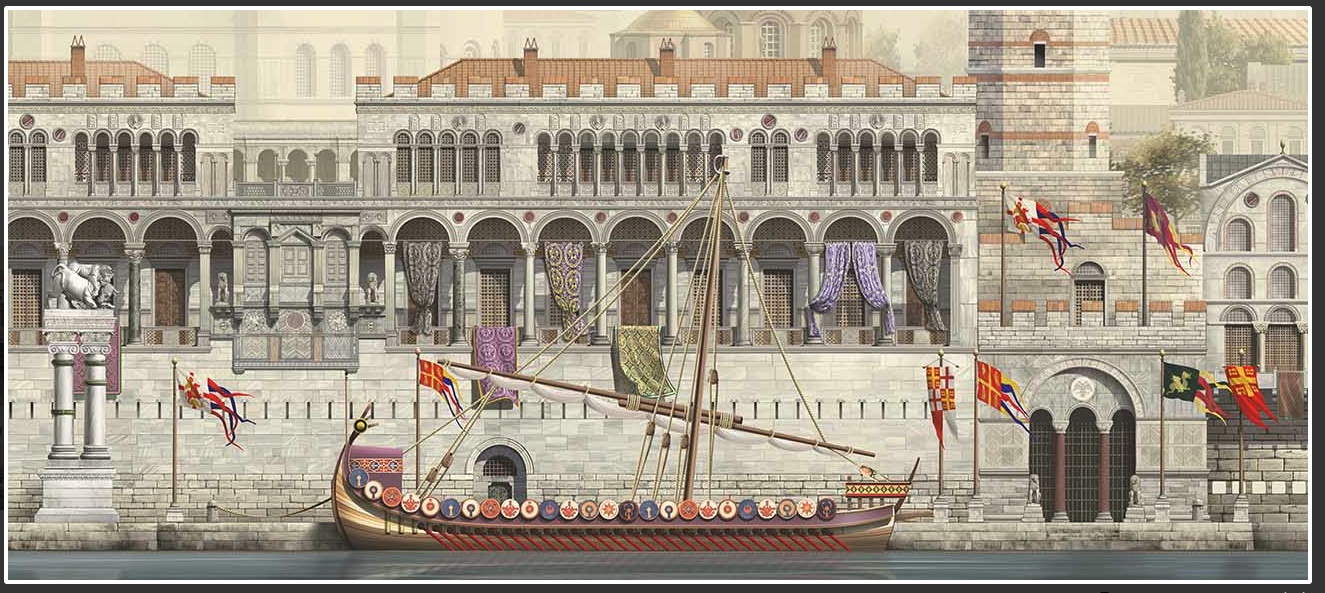

The twenty years that followed the return to Constantinople were absorbed in the work of restoring the Empire and adjusting the quarrels of the partisans of the rival patriarchs. Of the restoration it is enough to say that, as in all similar efforts during the last three centuries of the Empire, it consisted in recovering the revenue of the Court and enriching the Emperor’s supporters, not in any serious attempt to revive the industries and commerce of the Empire.34 Nor were Michael’s attempts to make foreign alliances much more successful. Foiled in his efforts to secure the interest of Latin rulers, he turned to the Servians and Bulgarians. In 1272 he decided that his second daughter, Anna, should marry the King of Servia. Theodora had some misgiving that the barbaric Servians were unfit to receive her daughter, and she directed the ministers who took Anna to the frontier to send on in advance a party to explore the Servian Court, and to linger sufficiently on the journey to receive their report. It proved a wise precaution. The Servians had gathered round the advance party like—as described in the Byzantine chronicles—a group of savages. Anna’s eunuchs excited their intense curiosity, though not their admiration, and the superb equipment of the princess was heatedly criticized. They brought out Anna’s prospective mother-in-law, a dirty and coarsely dressed woman, to show the Greeks a model queen. They also stole the imperial horses. So the advance party hastily sent a report to the ministers who lingered on the way with Anna and she was conducted back to her mother.

The twenty years that followed the return to Constantinople were absorbed in the work of restoring the Empire and adjusting the quarrels of the partisans of the rival patriarchs. Of the restoration it is enough to say that, as in all similar efforts during the last three centuries of the Empire, it consisted in recovering the revenue of the Court and enriching the Emperor’s supporters, not in any serious attempt to revive the industries and commerce of the Empire.34 Nor were Michael’s attempts to make foreign alliances much more successful. Foiled in his efforts to secure the interest of Latin rulers, he turned to the Servians and Bulgarians. In 1272 he decided that his second daughter, Anna, should marry the King of Servia. Theodora had some misgiving that the barbaric Servians were unfit to receive her daughter, and she directed the ministers who took Anna to the frontier to send on in advance a party to explore the Servian Court, and to linger sufficiently on the journey to receive their report. It proved a wise precaution. The Servians had gathered round the advance party like—as described in the Byzantine chronicles—a group of savages. Anna’s eunuchs excited their intense curiosity, though not their admiration, and the superb equipment of the princess was heatedly criticized. They brought out Anna’s prospective mother-in-law, a dirty and coarsely dressed woman, to show the Greeks a model queen. They also stole the imperial horses. So the advance party hastily sent a report to the ministers who lingered on the way with Anna and she was conducted back to her mother.

In the same year Eulogia’s daughter Maria was married to the King of Bulgaria, but the marriage brought little profit to the Emperor. Eulogia had now quarrelled with Michael. She took the part of the ex-patriarch Germanus, and she and her daughters and her favourite monks threw themselves so ardently into the religious quarrel, which the Emperor vainly endeavoured to settle, that Michael was very angry with them. Monks now travelled constantly between the young Queen of Bulgaria and the Empress-nun, her mother, and gravely disturbed Michael’s work. After a time Maria sent some of the monks to Palestine to induce the Sultan to harass her uncle’s territory, and she even persuaded her husband to declare war on him. Michael hated the monks as heartily as Eulogia loved them, and he at length expelled his sister from the capital. When he went on to propose a union of the Latin and Greek Churches, and induced a synod at Constantinople to acknowledge the supremacy of the Pope, Eulogia’s love was turned into violent hatred of the Emperor.

Martha seems to have died during the struggle, and Theodora was too weak, or too indifferent to clerical matters, to take any part in it. She must have watched with disdain the last vain efforts of her unscrupulous husband to escape the dangers which threatened him. In the early winter of that year (1282) he set out to crush a rebellious noble of the Ducas family. Theodora tried272 in vain to dissuade him from leading an expedition to Thrace in such a bad season, and a month later she received the news of his death.

Her son Andronicus now took the purple, and, as Andronicus was orthodox and his royal aunt Eulogia at once returned to the scene, Theodora had a more dreary time than ever. Her brother was damned, Eulogia insisted, and his remains and memory were not to be honoured by the pompous ceremonies of the Greek Church. The young monarch—he was in his twenty-fifth year—bent to her commands, and the body of Michael was buried, almost without a prayer, in the military camp where he had died. Theodora feebly protested, and was assured by the fanatical Eulogia that her own soul was in danger, and her name could not be included in the list of those who were commended to the prayers of the faithful in St Sophia until she had purged herself of her guilt. She was compelled to sign a repudiation of the authority of the Pope, which would cost her little, and to promise that she would not ask the prayers of the Church for her husband.

Into the appalling struggle of the Church factions which followed we need not enter. One of the best historians of the time, who saw the Empire slowly perishing while its whole soul was absorbed in this quarrel, bitterly observes that “for the sake of a single coin both sides were prepared to take oaths so horrible that the pen cannot describe them.” One day they appealed to miracle; each side wrote out a statement of its case, and a vast crowd gathered to see the two rolls of parchment cast into the flames and howl for the intervention of God in favour of the just cause. But both documents were burned to ashes, and the ferocious struggle continued for decades, while the Turks spread over the Asiatic provinces, pirates swarmed in all the seas, and the Venetians and Genoese captured all the trade of the Empire. Eulogia disappears in the midst of this struggle, fighting to the last in the cause of the monks, a pathetic example of the way in which the age perverted its ablest and most spirited women.

Theodora lived on for twenty-two years, and saw two new Empresses enter the palace, but the chroniclers of the time are too much occupied with the ecclesiastical controversy to tell us much of the personal life of the Court. George Pachymeres has left us a large volume on the history of his times, but fully one-half of it is taken up with the patriarchal struggle. I will therefore be content to tell the later sufferings of Theodora, and then return to the Empresses whom her son Andronicus put on the throne.

The family of the Emperor Michael had consisted of four sons, three daughters and two illegitimate daughters. The daughters were bestowed upon various nobles or petty monarchs, and of the four sons three survived to intrigue, or suspect each other of intriguing, for the throne. Andronicus was the eldest, and he succeeded his father without opposition. The second son, Constantine, had, however, been the favourite of his parents; he had received great wealth from Michael, and it was known that Michael intended, when death closed his career, to set up Constantine as an independent Emperor in Greek territory. From the first, therefore, Andronicus regarded his younger brother with a jealous eye. Constantine was a good-looking and very popular youth, very liberal with his money and surrounded by friends. Unfortunately he had, like most of the Greeks of the time, little or no self-control, and in 1291 he gave his brother an opportunity to destroy him.

Some short time before 1291 Constantine had married the daughter of Raul, one of the chief officials of the Court. She was a beautiful and somewhat vain young woman, very conscious of her new dignity. On the Feast of the Apostles, one of the many days on which the ladies of Constantinople were wont to pay ceremonious visits to the ruling Empress, Constantine’s wife—we do not know her name—repaired in great274 splendour to the palace of Irene. In the hall sat an aged and noble dame named Strategopulina: in other words, a lady of the distinguished Strategopulos family, and herself a niece of a former Emperor. She had arrived too early for the reception, and sat on a couch without the Empress’s chamber. On account of her age and rank Strategopulina did not rise, as she ought to have done, when Constantine’s wife passed, and the offended princess returned to her husband in such rage that she fell ill. Most probably the old lady knew that Andronicus and his wife would not be very displeased with her action. But Constantine, egged on by his wife, took the matter in his own hands. Acquainted as we are with the morals of Constantinople, we are hardly surprised to learn that Strategopulina was believed, in spite of her age, to be intimate with one of her servants. Constantine sent some of his servants to flog this man in public, and drag him naked round the Forum.

The scandal, the storm of chatter, and the gross injury to one of his wife’s friends, angered Andronicus, and for some time he looked darkly on his brother. Constantine was alarmed, and took pains to conciliate him, but he was displaced from his position at Court and sent on some mission to Nymphæum.

With his sixty thousand gold pieces a year and his pretty wife Constantine would still find life desirable in Asia Minor. Presently, however, Andronicus came to Nymphæum, and took up his residence in the old palace of the Nicene Emperors. To this palace Constantine was summoned one morning in March (1291). He found it full of soldiers, learned that his brother had found him guilty of treason, and was given into custody. His luxurious belongings and his great income were confiscated by Andronicus, and he was destined to spend the remaining fifteen years of his life in a new and particularly ignominious prison. Andronicus was afraid to lodge him in a fixed jail, lest his supporters should free him and start a revolt, and he therefore had a portable275 prison—a litter converted into a strong-barred cage—made for him.

In this plight Theodora found her handsome son when, a month of two later, Andronicus brought him to Constantinople. The Emperor had now taken a decisive step, and he disregarded his mother’s prayers and tears. When she pleaded that her son had been convicted, without trial, on the secret denunciation of a monk, Andronicus merely summoned a council in the palace and compelled his obsequious courtiers to ratify his sentence. Theodora continued to assail him, but she had never had much influence in the administration, and under Andronicus she was completely powerless. Andronicus gave her no opportunity to thwart his policy by intrigue or violence. When he was compelled to go into the provinces, he took Constantine with him in his portable prison, and the miserable young prince, dressed and shaven as a monk, dragged out year after year without the least prospect of escape. The third and youngest brother, Theodore, took warning by Constantine’s fate, put off all signs of royal estate, and, living as a private citizen, endeavoured to disarm the jealousy of the Emperor. These misfortunes, and the thick gathering of clouds about the Empire, saddened the last years of Theodora’s long life. The regaining of Constantinople had put no new spirit, no healthier blood, into either people or Court. The Byzantine power was doomed, and the last sad glances of the aged Empress fell on a capital fiercely rent with ecclesiastical quarrels, a shrunken Empire trodden under the feet of the Turk, and a sea swept by innumerable pirates. She died in 1304, respected and superbly lamented by the citizens of Constantinople. Without strength of character to make her mark on the life of the Empire during nearly fifty years of imperial authority, she had at least kept her slender record unstained by crime or vice in a criminal and vicious world. At the most we can regret only that she clung so faithfully to Michael Paleologus through all the crimes and deceits of his tortuous career.

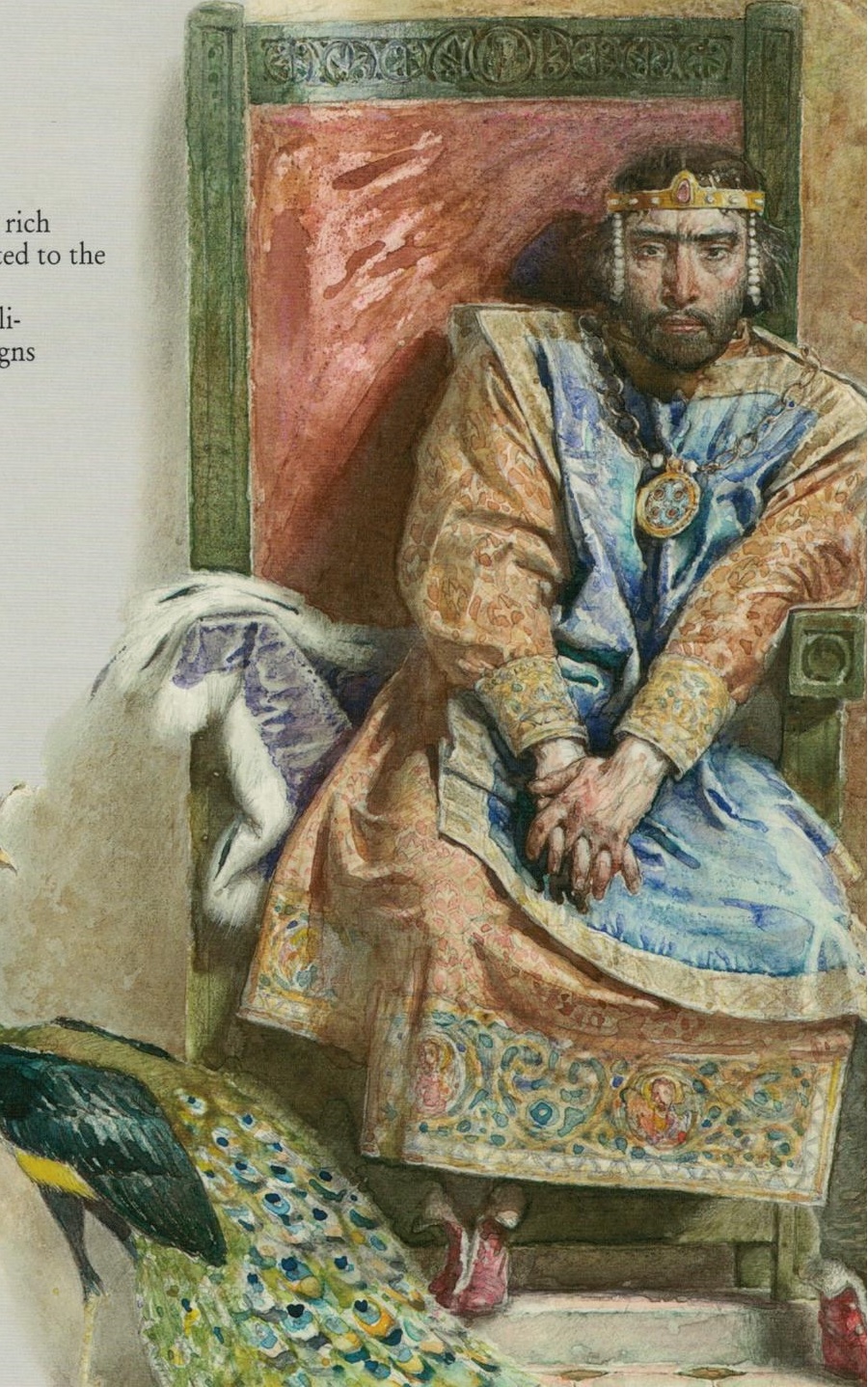

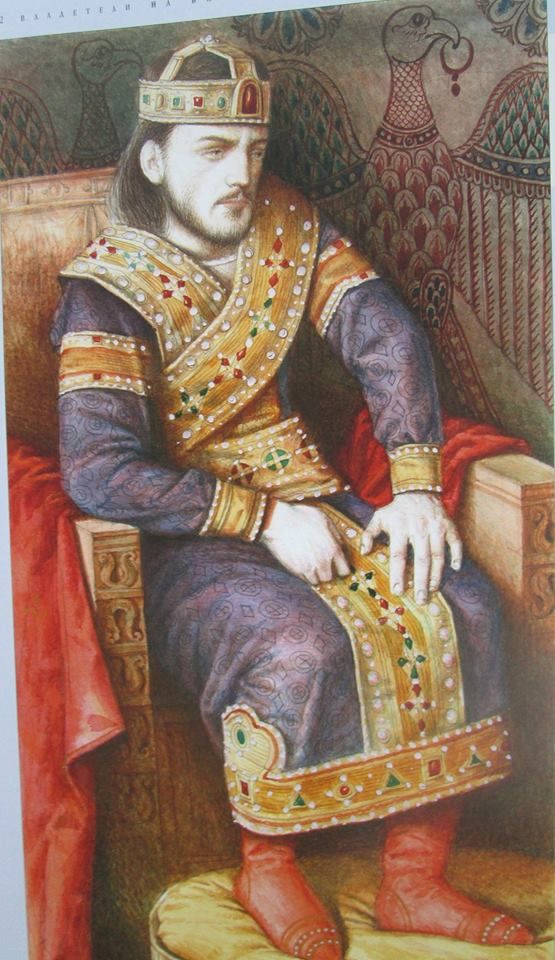

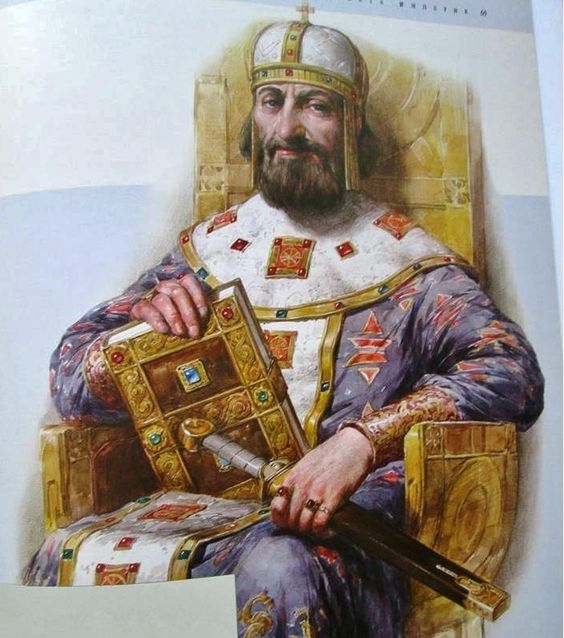

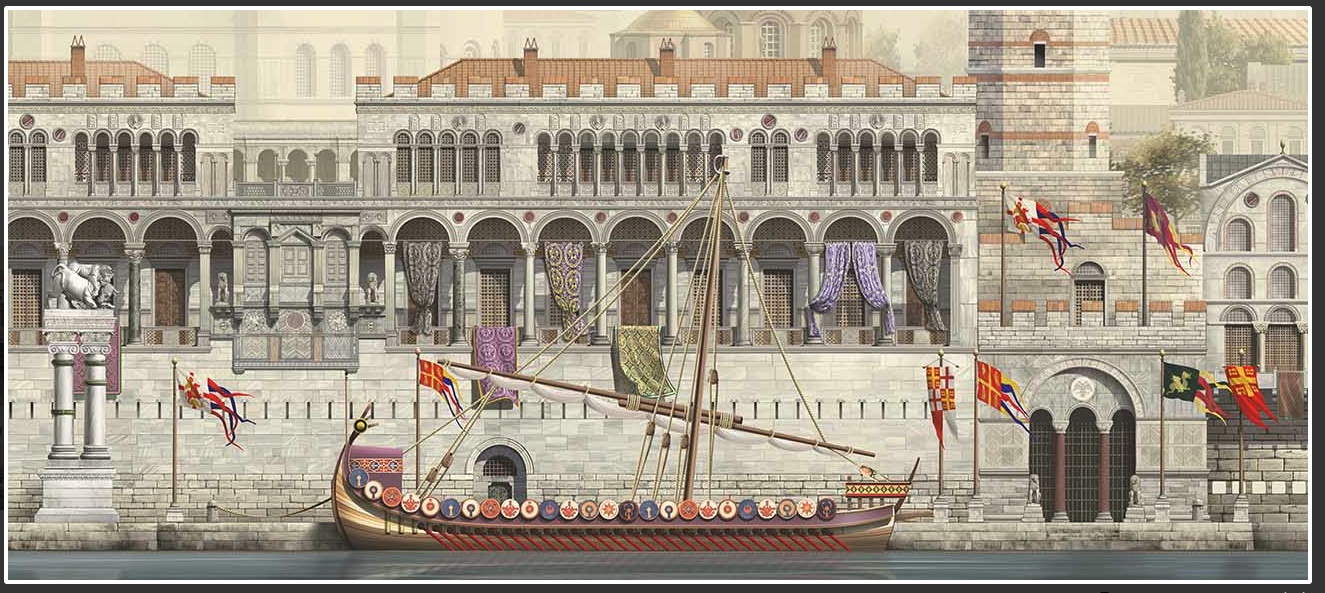

Emperor John I Tzimiskes, the murderer of his uncle Nikephorus II Phocas in his bed in the Boukoleon Palace. John married his uncle's wife, who was his co-conspirator in the assassination.

Emperor John I Tzimiskes, the murderer of his uncle Nikephorus II Phocas in his bed in the Boukoleon Palace. John married his uncle's wife, who was his co-conspirator in the assassination.

The twenty years that followed the return to Constantinople were absorbed in the work of restoring the Empire and adjusting the quarrels of the partisans of the rival patriarchs. Of the restoration it is enough to say that, as in all similar efforts during the last three centuries of the Empire, it consisted in recovering the revenue of the Court and enriching the Emperor’s supporters, not in any serious attempt to revive the industries and commerce of the Empire.

The twenty years that followed the return to Constantinople were absorbed in the work of restoring the Empire and adjusting the quarrels of the partisans of the rival patriarchs. Of the restoration it is enough to say that, as in all similar efforts during the last three centuries of the Empire, it consisted in recovering the revenue of the Court and enriching the Emperor’s supporters, not in any serious attempt to revive the industries and commerce of the Empire.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints