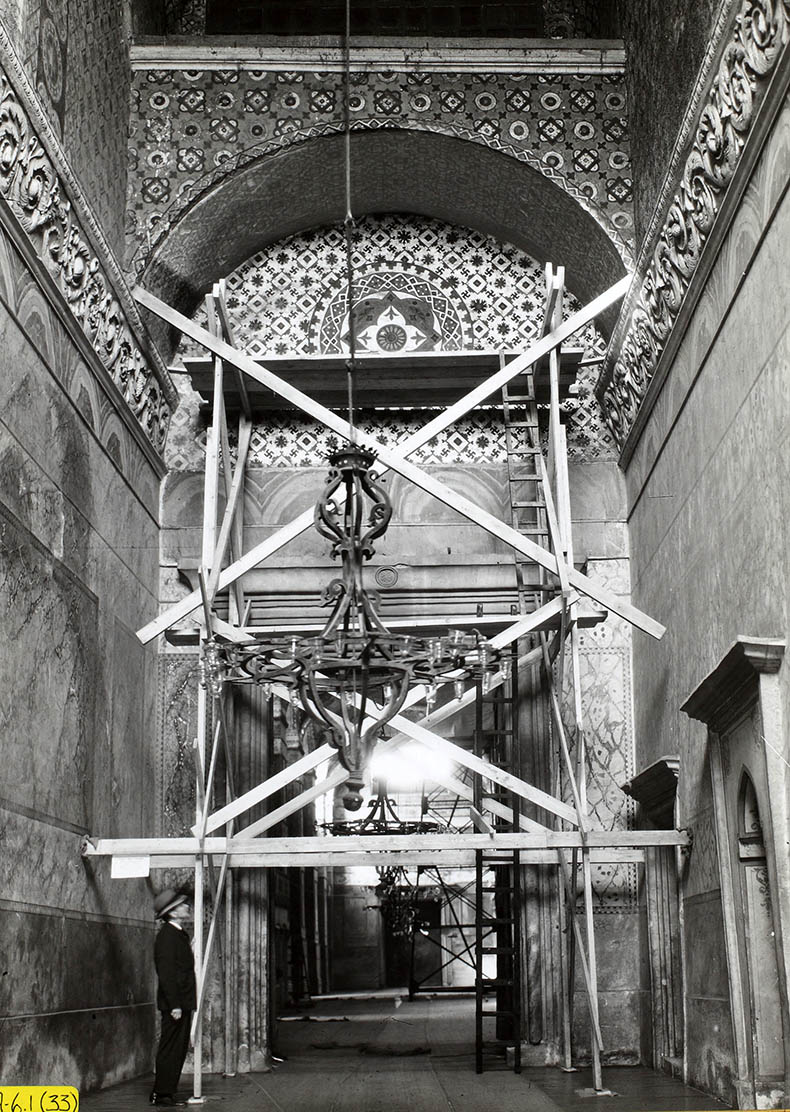

This picture was taken in natural light which is how the people in Constantinople would have seen it. The figure of Mary with Christ, dating here from the 10th century, is the same image used in the apse mosaic of the Theotokos. This is the 'official' Madonna of Hagia Sophia. In Ottoman times there was a wooden chandelier hanging in front of it, which obscured the view from the floor of the vestibule. It was removed in the 1930's.

The Southern Vestibule is a deep, entry-hall, 13.79 m. long, which lies on the axis of the narthex and immediately to the south of it. It became the primary entrance to Hagia Sophia, except when great crowds on special days were expected; then the western doors of the narthex were all opened to the atrium.

Entering the church from the Augusteion a visitor would have seen the huge equestrian statue of Justinian on his towering column on the same visual line of his dome, which acted as a visual backdrop to the statue. The two would have been directly connected to each other and the column was placed closer to the church to achieve the desired effect. The column was dedicated in 543 and the figure faced east. We are told that an acrobat who performed in the Hippodrome crossed on a cable strung from the dome of Hagia Sophia to the top of the statue. To the left as one entered the church on could see the great porphyry column of Constantine, crowned with a monolithic gilt-bronze statue of him. This column was the tallest monument in the city, taller than Trajan's column in Rome. The statue fell down in the 12th century and was replaced by a gilt cross. The column can still be seen. So these two monuments would have been seen by anyone entering the church through the vestibule and are tied directly to the mosaic and its location in the church.

The floor of the narthex shows extreme wear on the other side of this door indicating how much traffic it received. The marble is highly fragmented and has been replaced there.

The vestibule originally functioned originally as a sheltered passage for people and processions moving from outside Hagia Sophia into the narthex. Later it also functioned as the main entrance to the Patriarchal Palace which was on the right of it. It used to connect to the south-west ramp on the east and to rooms attached to the atrium. There was a small room and tiny cupboard here for the Emperor to leave his crown before entering the church. In Ottoman times the doors were sealed up. The vestibule is irregular in plan and the doorways are off center. The barrel vault above the mosaic was added at the same time as the mosaic. Some years ago Ernst Hawkins studied the blue and white stucco cornices and concluded they are original and date from the time of Justinian. The walls were originally covered with colored marbles, but now have been replaced with horrible fake marble paintings. The ceiling vaults and upper walls of the Vestibule still have their ornamental carpet mosaics, which also date from 6th century. These mosaics have been painted over to replace missing sections and to obscure crosses.

Notice the white patches of plaster on both sides of the panel at the bottom? Those were put on during the Fossati restoration of Hagia Sophia in 1845. When this panel was conserved and restored in the the 1930's by the Byzantine Institute they did not know what to do with them. They were not original to the mosaic. If they removed them there would have been big holes they would have to fill with new even whiter plaster. They were concerned a about how glaringly bright their new plaster additions were. They spent years trying different solutions to pull it down. Eventually they settled on mixing cobwebs in water and using it as a wash. You can read more about the work of the Byzantine Institute in Hagia Sophia here.

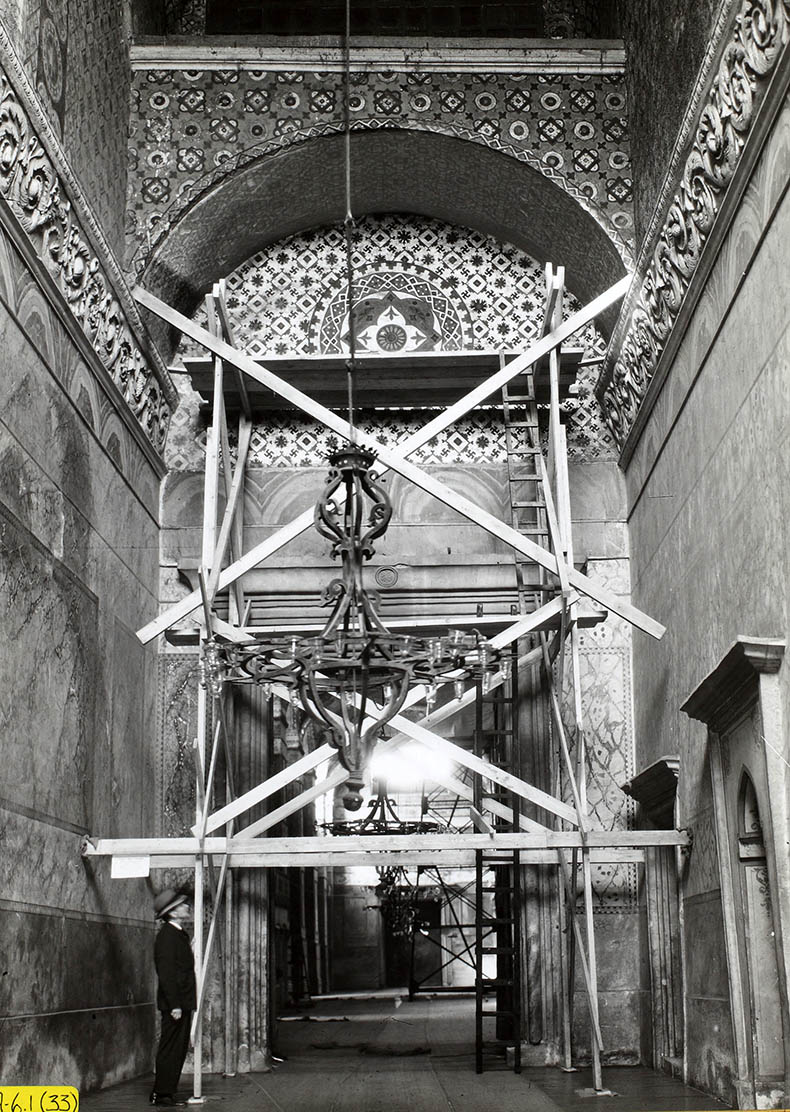

Above you can see the process of removing the Fossati plaster and decorative patterns that were painted in bright, oil-based house paint in 1845. These patterns were created by the Fossatis based on motifs they saw in the church. All of this paint was a bad idea that ended up destroying most of the Byzantine mosaics they uncovered. In a few short years the oil paint was blistering and pealing off the walls - especially in the vaults - and the mosaics went with them. The Fossatis painted designs over the mosaic crosses from the time of Justinian. The paint darkened and stained the mosaic - you can still see the effects.

The restorers worked on scaffolds from the top down, securing loose mosaic and applying clamps to reattach the plaster mosaic bed as they went. Removing the milky white film was one of the last things done in the restoration of the 1930's

The regal image of the Mother of God enthroned reached its peak in the Imperial court of Byzantium. Here in the midst of Hagia Sophia - hovering over the entrance to the church in a golden glory - she reigns over both emperor and the common man; all equal before Christ whom she shelters in her lap like a living temple linking heaven and earth. One might suggest that her throne, which is based on the actual throne of the emperors, has windows like the apse of the church on it's back and arms. This could reflect the sacrifice of Christ on the altar of the sanctuary. Would ancient visitors to Hagia Sophia have understood these allusions? Certainly the deacons, deaconesses and clergy of the church would have used this mosaic to teach theology and the Gospels to their students. In Byzantium it was not possible to have been passive observer of art in churches like this. Everyone was required to understand and profess the Apostle's Creed.

The image of Justinian I holding a model of Hagia Sophia along with the Virgin appeared for hundreds of years on the large lead seals that were attached to documents of the Court of the Deacons and Clergy which reviewed such things as sanctuary cases. The design of the seal is directly related to this mosaic. In 431 the Emperor Theodosius II expanded sanctuary to include the entire precinct of Hagia Sophia. Sanctuary was claimed by accused murders. The Court was held here in the vestibule and in also in the inner narthex so the public could attend.

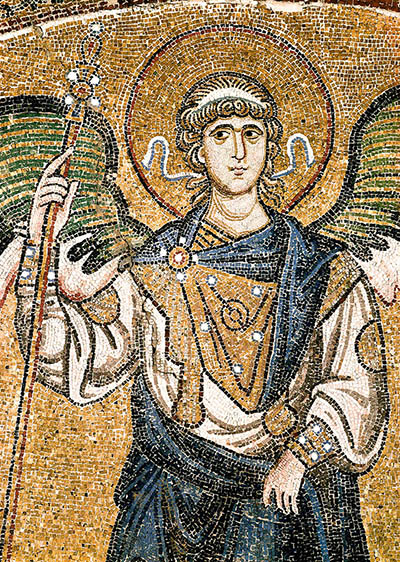

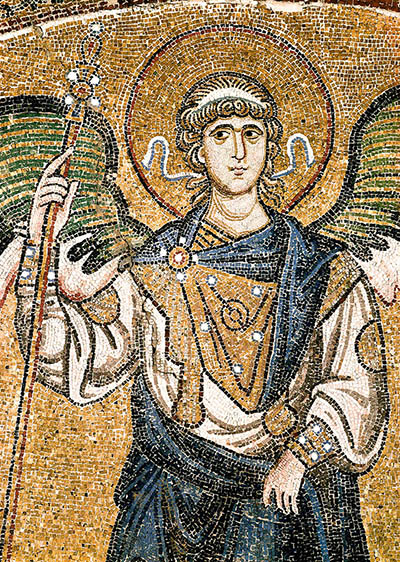

Some have speculated that the Southern Vestibule could have been the "Pronaos of the Archangel Michael", so-called because there was a famous mosaic icon of him there which has vanished. The Pronaos figured in historical accounts and myths about the building of Hagia Sophia and was described by Russian pilgrims in the late Byzantine period. George Majeska has paraphrased the story, which I repeat here:

Some have speculated that the Southern Vestibule could have been the "Pronaos of the Archangel Michael", so-called because there was a famous mosaic icon of him there which has vanished. The Pronaos figured in historical accounts and myths about the building of Hagia Sophia and was described by Russian pilgrims in the late Byzantine period. George Majeska has paraphrased the story, which I repeat here:

"During the building of St. Sophia a boy was set to guard the tools while the architects dined with the Emperor. As the boy was watching over the tools, the Archangel Michael appeared to him in the guise of a radiant eunuch and offered to stand guard over the church until the boy returned from delivering the eunuch's message to the Emperor concerning the name of the church and the importance of completing it quickly. Divining the identity of the eunuch, the Emperor cleverly sent the boy abroad, so that he would never return to the church of St. Sophia and the Archangel Michael would be forced to remain as its guardian."

The apparition was said to have occurred in the South Gallery, where the Deesis is located. It seems likely that the Pronaos was a separate building adjacent to the entrance of the Southern Vestibule that was demolished after the conquest. It was definitely located between Hagia Sophia and the Augusteon, which after the 6th century is always referred to as the forecourt of the church (peribolos) and not a forum. Many Byzantine churches had shrines to the Archangel Michael near their entrances to protect the building.

michael is the supreme commander - "archistrategos" - of the heavenly host

The name Michael in Hebrew means "He Who is like God" and he is first mentioned in the book of Daniel. In the Bible Michael is one of the great princes of heaven and rules the country of Israel. Michael is God's counterpoint to fight the evil one and he triumphs over Satan in the Book of Revelation, casting him and his host of rebel angels into the lake of fire. Christians began to venerate him specifically in the fourth and fifth centuries. As a heavenly power Michael does not have a physical, human-like form and his being cannot be expressed. Icons of him can only echo God's vast and infinite power as shown in the acts of the archangel. Angels can never be worshiped - they can only be venerated as symbols or gateways of prayer to God.

In the 15th century the former Augusteion was full of restaurants and inns that catered to pilgrims and after-church diners. Westerners noted how these inns had big stone tables and that all classes patronized them. When the Emperor and his family attended liturgy they had breakfast in the nearby Great Palace. Even in the last days of the empire a part of the Great Palace was maintained for use by the Imperial family when they visited Hagia Sophia. Right up until the 16th century the colossal equestrian statue of Justinian dominated this square, its base and stairs took up most of the space in the Augusteion.

A Russian pilgrim account tells us there was a great fountain on the right hand side were the so-called bapistery is located. This is another fountain besides the one in the atrium.

The worshiper entered through bronze portals into the Vestibule and traversing it he passed other bronze doors in the narthex. He saw the mosaic situated above this second doorway, where the subject is still illuminated by strong light admitted through a large window in the south wall, directly opposite to it. The result is that now, as then, the mosaic, recessed beneath a semicircular arch, 1.83 m. deep, is well lit, and is clearly seen from the payment 6.45 m. below.

The mosaic probably dates to the late 900s. It could have been put up during the repairs conducted in Hagia Sophia by the Armenian architect, Trdat, between 986 and 994 when Hagia Sophia was closed. Its simplicity and 'classical' style resembles the miniatures in the famous Menologion of Basil II from the same time. Justinian is in the place of honor.

The mosaic probably dates to the late 900s. It could have been put up during the repairs conducted in Hagia Sophia by the Armenian architect, Trdat, between 986 and 994 when Hagia Sophia was closed. Its simplicity and 'classical' style resembles the miniatures in the famous Menologion of Basil II from the same time. Justinian is in the place of honor.

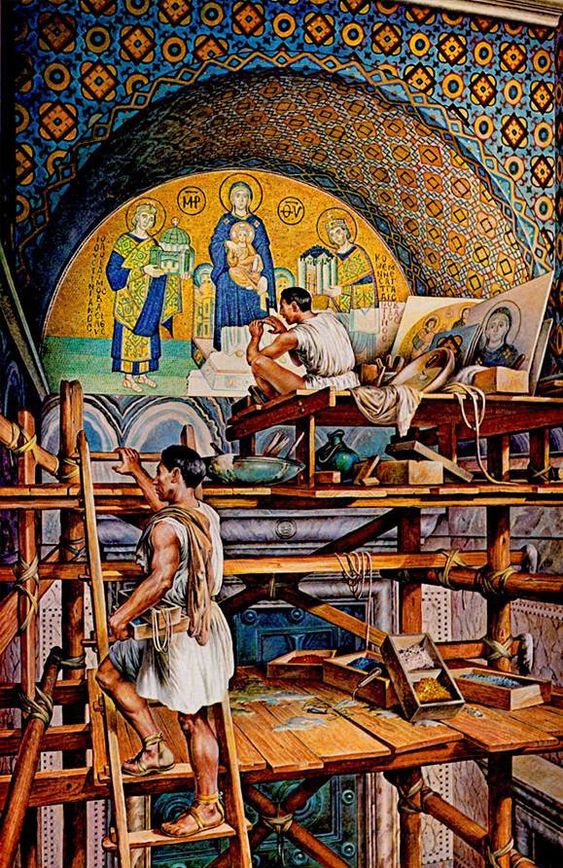

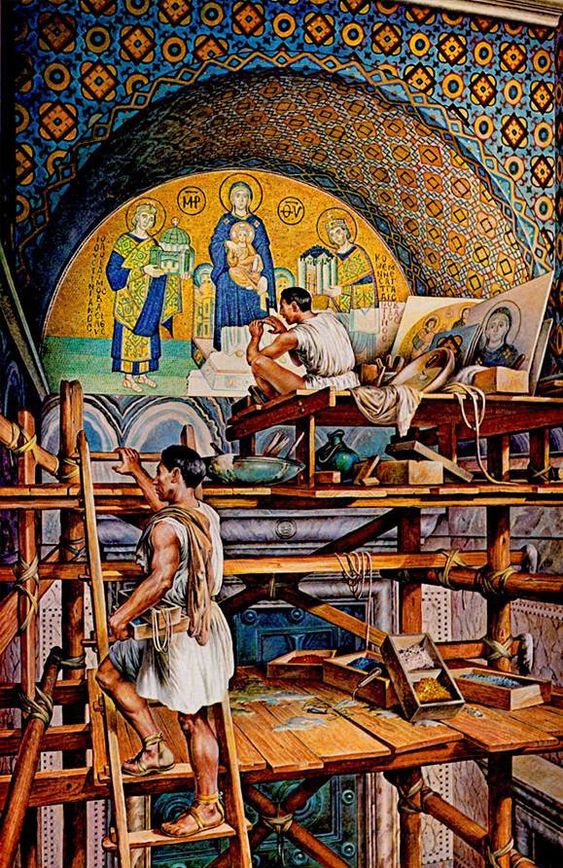

The illustration on the right of mosaic craftsmen erecting this mosaic is great. However, unless our artists were eunuchs they would have been bearded. They would have worn shoes, rather than sandals, and they would have worn heavier tunics made of wool or linen.

The historian Cedrenus tells us "the great Constantine was of medium height, with broad shoulders and a thick neck. His skin was ruddy, his hair neither thick nor curly, his beard sparse, his nose somewhat crooked, his eyes lion-like and his countenance most serene". Justinian is described by the historian Malasas as being "short in stature, broad chested, with a well shaped nose, fir skin, curly hair , a round face, handsome. but going slightly bald, with a florid countenance, and hair and beard going gray". Although these portraits might appear generalized to us today, they would have been modeled on real, contemporary portraits - that would have been available to the artists and used as prototypes.

Both emperors are wearing imperial vestments of the tenth century that are intentionally similar - almost like uniforms. This is meant to convey the harmony and continuity of imperial ceremonial of the time.

In my opinion Constantine and Justinian have been done by two different artists. Justinian's figure is more crudely drawn and has the same - even clumsy - hands with roughly drawn fingernails like we see in the Angel Gabriel in the apse and the mosaic of Christ in the Leo mosaic in the narthex. Justinian's face appears heavier and the modeling is more linear. With clothes like blue and green that were used for clothes artists usually had 3-4 shades of a color to choose from. Large faces and hands - flesh tones - are difficult to model with smooth gradient tones because there are fewer mosaic colors for an artist to work with. If can't just use different shades of white to convey flesh. Major features are often drawn in dark red, while green and gray cubes are set against rosy pink and white highlights. From a distance and in normal lighting these colors blend together, but in bright artificial light all of this is shown in sharp contrast. Constantine is a finer figure than Justinian. Maybe these emperors are based on real portraits and Constantine was better looking than Justinian.

The model of Hagia Sophia Justinian is carrying is very big and heavy - look at the size of the domes. This model shows that in Byzantine times it was painted in two shades of blue. The windows are all set in white marble frames. Just like today the roof is covered in sheets of gray lead (it's possible that some of the original lead sheets are still in place. However it is more likely the lead sheets on Hagia Sophia today are recycled from original ones, which were melted down and refashioned as needed). The cross on the dome is set in a great red circle and is gilded.

The model of Hagia Sophia Justinian is carrying is very big and heavy - look at the size of the domes. This model shows that in Byzantine times it was painted in two shades of blue. The windows are all set in white marble frames. Just like today the roof is covered in sheets of gray lead (it's possible that some of the original lead sheets are still in place. However it is more likely the lead sheets on Hagia Sophia today are recycled from original ones, which were melted down and refashioned as needed). The cross on the dome is set in a great red circle and is gilded.

In the face of the Virgin we can see the artist who made her has had to use lines of green and gray to roughly model it. Again, the artist was limited by the colors of the cubes they had to work with. If we compare this work to the faces of the Deesis we can better appreciate its beauty and supreme technical achievement. In the faces and hands hundreds of different tones are used and the size of the cubes are extremely small. This makes those figures very vivid and 'alive'.

The two emperors are dressed for "for church" in beautiful dark blue silken robes with long silk stoles that have been woven in gold and embroidered in dark red and teal-blue (in the mosaic the teal-blue color is made of very pretty milky glass cubes, see below). Imperial robes were made in special royal workshops near Hagia Sophia; the silk used was often the heavy and expensive 6 thread Samite weave (an example is on the right). The threads would come in multi-colors ad produced colorful patterns. Certain colors were reserved for the Emperor and there were published guides to what colored silks could be worn by different offices in the Imperial court. Even military generals were entitled to wear silk clothing and did so on campaign!

Often times the dye used to color silks was more valuable than the cloth itself. For example, it took 15 lbs of expensive dye to produce one yard of material. The famous Imperial purple color took huge numbers of shellfish to make the smallest about of dye. The stocks were over fished and the production of Imperial purple probably stopped in the 4th century. Later an Imperial purple made from a blend of colors was used instead. The dying of silk was a dangerous job, which was done by its own guild of workers and workshops. Thread or cloth could easily be ruined by a bad dye job, so the work involved risk. It was also unhealthy and a smelly activity that was required to be done in special areas or outside the city. Silk weaving and dying was often done by the Jews in Constantinople.

Often times the dye used to color silks was more valuable than the cloth itself. For example, it took 15 lbs of expensive dye to produce one yard of material. The famous Imperial purple color took huge numbers of shellfish to make the smallest about of dye. The stocks were over fished and the production of Imperial purple probably stopped in the 4th century. Later an Imperial purple made from a blend of colors was used instead. The dying of silk was a dangerous job, which was done by its own guild of workers and workshops. Thread or cloth could easily be ruined by a bad dye job, so the work involved risk. It was also unhealthy and a smelly activity that was required to be done in special areas or outside the city. Silk weaving and dying was often done by the Jews in Constantinople.

Byzantine silk weavers were so highly skilled in the production of luxury fabric that was the envy of the world. It was not only done for the Imperial court but there was a whole popular 'fashion' production or lower cost silks clothes from less expensive thread or blends.

There were also separate Imperial workshops that worked in gold thread for the Emperor. There were two types of gold thread, one was made of solid gold and another was made of silk or linen threads wrapped in sheets of thin gold. They also did silver embroidery. The first method was stiffer and heavier; fabric embroidered this way was almost a pure cloth of gold. The workshops received orders from the court for specific clients - even foreign rulers. They also kept a full stock of tailored outfits for the Emperor and his family, that were could pick from as needed. They also repaired Imperial clothes that needed restyling or replaced missing golden buttons. The Emperor's linen underwear was also of the finest quality and was embroidered in silk and wool. The gold embroidered linen towels made for the court were extraordinary and were given as gifts to other rulers. An example of gold embroidery created by the Imperial workshop is below:

The Samite weave was also used for curtains for the chancel screen and altar coverings in Hagia Sophia. The curtains were woven with images of Christ, His Mother and saints. An example can be seen below:

There were also workshops attached to the Imperial court who made all of the crowns and jeweled things that were required. An example of their production is the great "Bent-Cross" Diadem of Hungary you can see on the right. Imperial commissions like the famous church chalices of the Emperor Romanus, now in the Treasury of St. Mark's were made there.

the following is thomas whittemore's description of the mosaic from the 1930's with some changes and additions:

The interior surface of the arch which crowns the panel to be described is itself, as are the vaults and higher surfaces of the walls, covered with colored mosaic decoration in geometric patterns with minute repeating figures. The presence of a sacred representation at this spot was known from its mention in a document of the twelfth century. The image was described there very briefly. It is not known when the mosaic was first concealed after the Muslim conquest of the City. The Fossati restoration of 1847 exposed the mosaic and even made repairs to it, before reconciling it under a new layer of plaster and painted ornament. Finally, the plaster was removed by conservators and craftsmen of the Byzantine Institute of America - and the underlying work for revealed to the public in June 1935.

The interior surface of the arch which crowns the panel to be described is itself, as are the vaults and higher surfaces of the walls, covered with colored mosaic decoration in geometric patterns with minute repeating figures. The presence of a sacred representation at this spot was known from its mention in a document of the twelfth century. The image was described there very briefly. It is not known when the mosaic was first concealed after the Muslim conquest of the City. The Fossati restoration of 1847 exposed the mosaic and even made repairs to it, before reconciling it under a new layer of plaster and painted ornament. Finally, the plaster was removed by conservators and craftsmen of the Byzantine Institute of America - and the underlying work for revealed to the public in June 1935.

The Vestibule Mosaic

The mosaic is a Hymn of Laudation to the Mother of God; an Akathistos in color and light distinguished alike by its delicacy and vividness.

The mosaic fills more than half a circle, its width at the highest pint of the plaster cornice is 16 ft; its greatest height is 10 ft.

The subject presents a group of two Emperors on either side of the Virgin enthroned with the Infant Savior. The figures are inscribed with their name and titles. In the center the Virgin with her appellation of Mother of God. To our right, Constantine the Great as a saint; to our left, Justinian the First; both emperors are nimbate with halos. The Virgin holds the Infant in her lap. Constantine carries the City that bares his name. Justinian supports in his hands the Church of St. Sophia. The green ground beneath the figures is presented in four horizontal layers which grow darker as they recede. The background is bright gold mosaic which vibrates with every pulse of light and creating an air of celestial brilliance around the amethyst-blue figures. The mosaic is ragged along its edges; originally it was surrounded by a border of red tessellate, of which parts remain; at the base of the picture no less than eleven rows are missing.

The Mother of God

The Virgin, here presented as the Mother of God, is shown seated, facing the onlooker, holding on her knees the Child Jesus, also facing the onlooker. She holds in her hand a silk kerchief. The oval features of the Virgin, which are lit from high up on our left, are purely formal. The flesh is delicate, rose-shell in tint with green shadows; the eyes are same deep blue of her robes, the nose is long and straight; the mouth, which shows Fossati repair in plaster, is small and regular. The expression is remote and impassive, and betrays no emotion. The harmonious glance including the symmetry of the garment around the ears is classical. The upper part of the Virgin's body is wrapped in a maphorion. She is seated on its edge. The maphorion and stole are executed in the manner of the vestments of Emperors, which were silk.

The maphorion covers the head, forming a hood, and falls over the shoulders and great in short folds. The lose-fitting cap worn by the Virgin is of the finest silk with a delicately woven border. Gold ornaments, the segmenta, one in the center of the hood and one on each of her shoulders, adorn the maphorion: that are formed of four squares. The type of the segmenta is an early one, towards the year 1000 AD it was replaced by the segmenta of another type, having the shape of the cross or stars. The stole or the long garment the Virgin wears under the maphorion is of the same stuff, a lustrous silk of heavy woven thread. Beneath the stole we catch a glimpse of the slippers of soft gilded leather with an oval inset of read leather.

Above - putting up the scaffold to begin removing the plaster from the mosaic. The man is the dark suit and hat is Professor Thomas Whittemore, the man who spearheaded the restoration of the 1930's and gave birth to the Byzantine Institute. Here you can see the door to the 'Imperial' room on the right closest to the wall of the narthex. Closer in, also on the right, is the small 'Imperial' cupboard, where the crown might have been stored when the Emperor entered Hagia Sophia.

The Child

The Child is represented seated on the knees of the Virgin. He is blessing with the right hand in the manner of the Eastern Orthodox Church, the tip of the third finger touching the thumb. In the left hand he holds a scroll. The head of the Child is set full-face. It is oval with an unusually high and prominent forehead. The left brow is higher than the right. The eyes are almond shaped and are turned towards the left. The large dark reddish-brown pupils give depth to the expression. The nose is small and straight. The cheeks are full. The mouth breaks gently into a smile. The general impression is that of a face filled with thoughtful alertness and radiance and the whole figure seems ablaze with light. At the same time we are aware that the artist in his characteristic Byzantine pre-occupation to endow the Child with the miraculous attributes has assigned to the body of an infant the head of an adolescent.

Around the head of the Child is a cruciform nimbus. There is some Fossati restoration in it. The hand of the child is unduly large when compared with the other limbs of the body. The artist has done this to emphasize the benediction. The bare right foot is large in comparison with the body of the Child. The left foot is less visible and was partially destroyed by a bad Fosatti restoration which is very distracting since the foot is missing toes.

The Child is clothed in a gold chiton and gold himation. The treatment of the colors in both garments indicate that they are of the same make and are woven with metallic wefts. They have the same lustrous quality and silver highlights of such a fabric. It is noticeable that to produce this effect the cubes are set flat and not at an angle.

The Throne

The throne is represented in inverted perspective and is illuminated on the left. The throne produces the effect of being an autonomous generating source of light, not a mere reflecting object; the light seems to emanate from the body of the mosaic itself, and the throne appears all luminous within. It is very different from the one over the entrance in the Narthex; there the throne is a piece of place furniture, here it is an altar of light. The Virgin is seated on a cushion and her feet rest on a footstool.

The Emperors

Both Emperors are represented somewhat nearer to the beholder than the central figures, their feet being approximately in the line of the front of the footstool. They stand symmetrically and resemble each other, not only in the attitude of their bodies, but in their vestments and in their features. Yet, although they show the same facial type, they are not identical. The Emperors differ physically. The illuminated, ethereal figure of Constantine is in contrast with the more materialized figure of Justinian. The hair of Constantine is in the style that was usual in the representation of the Emperors in the early Byzantine epoch. Justinian is shown older than Constantine, his gaunt features are harder and headier. He looks rather into space than towards the Virgin and Child.

While the face of Constantine has a touch of sadness, Justinian does not share this. There is nothing in common between this wrinkled, conventionalized face and the historical portraits of Justinian in Ravenna and elsewhere.

The Emperors are full-robed in a long and rather closely fitting tunic of chiton reaching almost to the ankles. The chiton is blue, of the same shade and weave as the Virgin's tones; its front part is ornamented with two claves - broad vertical gold bands. Over the chiton the Emperors wear the divitission, which is of the same color as the chiton. The light spots on the garments here and on the other two figures are due to repairs by the Fosasati and conservators of the 1930's. In executing these repairs Fossati used tessellae taken from other parts of the mosaic.

The most sumptuous part of the imperial vestments its the loros, a long, wide band of gold cloth that wrapped the whole bodies of the Emperors. They are represented as made of a gorgeous heavy stiff brocade woven with metal threads of gold and silver, and they are embroidered with a pattern in green. These loroi on the mosaic are destitute of the precious stones and pearls that usually adorn this vestment of the Basileus. The form and ornamentation of the crowns are characteristic of the tenth and eleventh centuries. They are crowned with the imperial stemma, a gold circlet covered with enamel seeming to represent golden sard surrounded surmounted by a triple ornament composed of a cross of pearls flanked by a grape-shaped pearl set on a peg on each side. Pendants called prependulia hang from both sides, each consisting of three large pear shaped pearls - the Roman clenchi. In the center of each circlet in is a large cabochon emerald framed in a horseshoe setting. The shoes of the Emperors are of soft golden leather with seams of imperial red, and they are tied at the back of the ankle with a bow of similar color. From the model in Justinian's hands we can tell Hagia Sophia was painted two shades of blue in the 11th century and the dome is not gilded. Justinian would have had models like this of the church made for him to review in the planning stages. These models must have been saved in the archives, the Byzantines kept everything, in triplicate!

From the model in Justinian's hands we can tell Hagia Sophia was painted two shades of blue in the 11th century and the dome is not gilded. Justinian would have had models like this of the church made for him to review in the planning stages. These models must have been saved in the archives, the Byzantines kept everything, in triplicate!

The Inscriptions

The figure of the Virgin is accompanied by the usual monograms meaning Mother of God. The inscription by Constantine reads - Constantine, the great Emperor amongst the saints. That of Justinian reads - Justinian Emperor of illustrious memory.

Some have speculated that the Southern Vestibule could have been the "Pronaos of the Archangel Michael", so-called because there was a famous mosaic icon of him there which has vanished. The Pronaos figured in historical accounts and myths about the building of Hagia Sophia and was described by Russian pilgrims in the late Byzantine period. George Majeska has paraphrased the story, which I repeat here:

Some have speculated that the Southern Vestibule could have been the "Pronaos of the Archangel Michael", so-called because there was a famous mosaic icon of him there which has vanished. The Pronaos figured in historical accounts and myths about the building of Hagia Sophia and was described by Russian pilgrims in the late Byzantine period. George Majeska has paraphrased the story, which I repeat here: The mosaic probably dates to the late 900s. It could have been put up during the repairs conducted in Hagia Sophia by the Armenian architect, Trdat, between 986 and 994 when Hagia Sophia was closed. Its simplicity and 'classical' style resembles the miniatures in the famous Menologion of Basil II from the same time. Justinian is in the place of honor.

The mosaic probably dates to the late 900s. It could have been put up during the repairs conducted in Hagia Sophia by the Armenian architect, Trdat, between 986 and 994 when Hagia Sophia was closed. Its simplicity and 'classical' style resembles the miniatures in the famous Menologion of Basil II from the same time. Justinian is in the place of honor. The model of Hagia Sophia Justinian is carrying is very big and heavy - look at the size of the domes. This model shows that in Byzantine times it was painted in two shades of blue. The windows are all set in white marble frames. Just like today the roof is covered in sheets of gray lead (it's possible that some of the original lead sheets are still in place. However it is more likely the lead sheets on Hagia Sophia today are recycled from original ones, which were melted down and refashioned as needed). The cross on the dome is set in a great red circle and is gilded.

The model of Hagia Sophia Justinian is carrying is very big and heavy - look at the size of the domes. This model shows that in Byzantine times it was painted in two shades of blue. The windows are all set in white marble frames. Just like today the roof is covered in sheets of gray lead (it's possible that some of the original lead sheets are still in place. However it is more likely the lead sheets on Hagia Sophia today are recycled from original ones, which were melted down and refashioned as needed). The cross on the dome is set in a great red circle and is gilded.

Often times the dye used to color silks was more valuable than the cloth itself. For example, it took 15 lbs of expensive dye to produce one yard of material. The famous Imperial purple color took huge numbers of shellfish to make the smallest about of dye. The stocks were over fished and the production of Imperial purple probably stopped in the 4th century. Later an Imperial purple made from a blend of colors was used instead. The dying of silk was a dangerous job, which was done by its own guild of workers and workshops. Thread or cloth could easily be ruined by a bad dye job, so the work involved risk. It was also unhealthy and a smelly activity that was required to be done in special areas or outside the city. Silk weaving and dying was often done by the Jews in Constantinople.

Often times the dye used to color silks was more valuable than the cloth itself. For example, it took 15 lbs of expensive dye to produce one yard of material. The famous Imperial purple color took huge numbers of shellfish to make the smallest about of dye. The stocks were over fished and the production of Imperial purple probably stopped in the 4th century. Later an Imperial purple made from a blend of colors was used instead. The dying of silk was a dangerous job, which was done by its own guild of workers and workshops. Thread or cloth could easily be ruined by a bad dye job, so the work involved risk. It was also unhealthy and a smelly activity that was required to be done in special areas or outside the city. Silk weaving and dying was often done by the Jews in Constantinople.

The interior surface of the arch which crowns the panel to be described is itself, as are the vaults and higher surfaces of the walls, covered with colored mosaic decoration in geometric patterns with minute repeating figures. The presence of a sacred representation at this spot was known from its mention in a document of the twelfth century. The image was described there very briefly. It is not known when the mosaic was first concealed after the Muslim conquest of the City. The Fossati restoration of 1847 exposed the mosaic and even made repairs to it, before reconciling it under a new layer of plaster and painted ornament. Finally, the plaster was removed by conservators and craftsmen of the Byzantine Institute of America - and the underlying work for revealed to the public in June 1935.

The interior surface of the arch which crowns the panel to be described is itself, as are the vaults and higher surfaces of the walls, covered with colored mosaic decoration in geometric patterns with minute repeating figures. The presence of a sacred representation at this spot was known from its mention in a document of the twelfth century. The image was described there very briefly. It is not known when the mosaic was first concealed after the Muslim conquest of the City. The Fossati restoration of 1847 exposed the mosaic and even made repairs to it, before reconciling it under a new layer of plaster and painted ornament. Finally, the plaster was removed by conservators and craftsmen of the Byzantine Institute of America - and the underlying work for revealed to the public in June 1935.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints