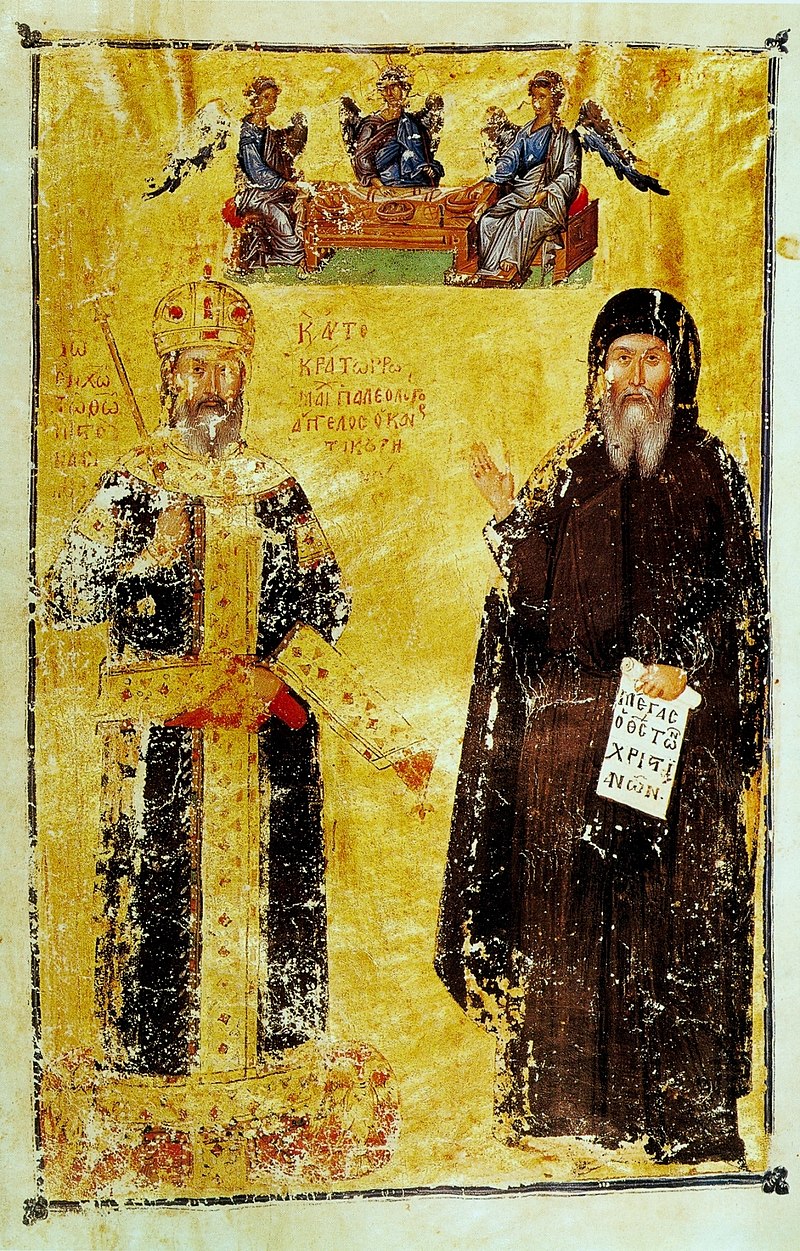

Andronicus II and Irene of Montferrat

The story of the unfortunate Theodora has led us to make a somewhat premature excursion into the fourteenth century. We have now to return a few decades, in order to begin the story of the Empress Irene, who succeeds her in the gallery of prominent Empresses.

The story of the unfortunate Theodora has led us to make a somewhat premature excursion into the fourteenth century. We have now to return a few decades, in order to begin the story of the Empress Irene, who succeeds her in the gallery of prominent Empresses.

Andronicus had in his sixteenth year married Anna of Hungary, a daughter of Stephen V. One of the daughters of Theodore Lascaris, the first Nicene Emperor, had married a King of Hungary, so that the daughter of Stephen V. had Byzantine blood—the blood of the Angeli family—in her veins. Her mother, however, was not of royal, or even noble, birth. Stephen had fallen in love with a pretty Choman captive, and married her, and the beautiful young girl whose hand Michael asked for his son was the issue of their marriage.

At her baptism according to the Greek rite her name was changed to Anna, and she, with her husband, received the crown of a junior Empress. Unfortunately she died the year before Andronicus attained supreme power, and we have merely to record that she left two sons, Michael and Constantine, to maintain the valuable dynasty of the Paleologi.

As Andronicus intended that one or other of these sons should inherit the purple, he did not seek his second wife among the more powerful courts of Europe. Two or three years after his accession to the throne he married Irene, daughter of the ruling Marquis of Montferrat. At the time she was a very pretty little maiden of eleven summers, and Andronicus may be excused for overlooking the possibility that, even if there were no powerful Court to espouse or create her interests, there might be a character in the lady herself which would interfere with his designs. For some years nothing occurred to make him regret his choice.

In the Blachernæ and Bucoleon palaces, or in the old Nicene mansions, Irene slowly grew up to womanhood, and added three sons and a daughter to the imperial family. The daughter, Simonides, will interest us no less than the sons, and an interesting light may be thrown on the character of the time by telling the origin of her very unusual name.

Andronicus desired to have a daughter, and was in despair when Irene had, in succession, three stillborn female children. A daughter, at Constantinople, meant a useful foreign alliance; though Constantinople never seems to have given any aid to the Courts from which it drew its own Empresses. In the year 1292 Irene again approached childbirth, and the anxious Emperor consulted “a venerable and experienced matron” in regard to his hope. Acting on her advice he set up, in a room of the palace, statues of the Twelve Apostles, with candles of exactly equal weight and size before each. A group of monks were then introduced to pray energetically for the issue, the candles were lighted, and careful watch was made to see which of the candles burned the longest. The apostle Simon won the contest, and it was resolved that the forthcoming little daughter should be put under his protection and named Simonides. The superstition must have gained enormous prestige when a daughter was born, and lived to experience a number of highly interesting, though not very apostolic, adventures.

Andronicus desired to have a daughter, and was in despair when Irene had, in succession, three stillborn female children. A daughter, at Constantinople, meant a useful foreign alliance; though Constantinople never seems to have given any aid to the Courts from which it drew its own Empresses. In the year 1292 Irene again approached childbirth, and the anxious Emperor consulted “a venerable and experienced matron” in regard to his hope. Acting on her advice he set up, in a room of the palace, statues of the Twelve Apostles, with candles of exactly equal weight and size before each. A group of monks were then introduced to pray energetically for the issue, the candles were lighted, and careful watch was made to see which of the candles burned the longest. The apostle Simon won the contest, and it was resolved that the forthcoming little daughter should be put under his protection and named Simonides. The superstition must have gained enormous prestige when a daughter was born, and lived to experience a number of highly interesting, though not very apostolic, adventures.

Another incident of the same year illustrates a different aspect of high life in the Eastern metropolis. Theodore, the younger brother of Andronicus, had now reached a marriageable age, and was, as I said, observing a very discreet behaviour in view of the recent fate of his brother Constantine. He bore the lower dignity of “Despot,” and was careful not to aspire to anything more than the278 slender circle of gold, with few jewels, which marked that dignity. Theodora had earnestly pressed her son to grant Theodore the title of Augustus, as it was customary to do, but he gravely replied that he had made some mysterious vow in earlier years which prevented him from doing so. He now decided to marry Theodore to the daughter of Muzalo, one of his chief ministers.

They were betrothed, but before the day of the marriage arrived Muzalo’s daughter was found to be in a painful condition, as a result of too great a liking for a cousin of hers. Betrothal was a very solemn ceremony in the eyes of the Greek Church, and it took a special synod of the bishops to determine that in this case the bond was invalid. The affections of Theodore were transferred to the daughter of another official, and, to reward the faithful services of her father, the soiled hand of Muzalo’s daughter was bestowed on Constantine, the second son of Andronicus and Anna. Experience had taught Andronicus that, if his eldest son, Michael, was to succeed him, all others must be kept away from the throne.

They were betrothed, but before the day of the marriage arrived Muzalo’s daughter was found to be in a painful condition, as a result of too great a liking for a cousin of hers. Betrothal was a very solemn ceremony in the eyes of the Greek Church, and it took a special synod of the bishops to determine that in this case the bond was invalid. The affections of Theodore were transferred to the daughter of another official, and, to reward the faithful services of her father, the soiled hand of Muzalo’s daughter was bestowed on Constantine, the second son of Andronicus and Anna. Experience had taught Andronicus that, if his eldest son, Michael, was to succeed him, all others must be kept away from the throne.

A third curious incident of the time may be recorded to illustrate the kind of world in which Irene grew to womanhood. The fierce struggle of the Arsenians and the Josephites still enlivened the environs of St Sophia, but the controversy entered upon a new phase after the imprisonment of Constantine. The young prince had been denounced to his brother by a monk who was a favourite of the patriarch, and, as this became known, the opponents of the patriarch assailed him with a furious tempest of invective. Nearly the whole of his clergy turned against him, and the charges they made against his personal character—charges which were loudly echoed in the public streets—were of the most sordid nature. He was compelled to resign, but he planned an elaborate revenge. He wrote a letter in which he invoked eternal punishment on the Emperor and all who had joined in his humiliation, and, in the279 characteristic Byzantine vein of ruse and intrigue, concealed the letter in one of the holes on the roof of St Sophia where the pigeons nested. He then retired to a monastery and contemplated with malicious joy the spectacle of the priests and citizens going about their work with this dire and authentic sentence of excommunication suspended over their heads.

A year later the vase containing the letter was found by some youths who had sought pigeons’ eggs, and a panic seized the Court and city. For twelve months they had all lived, unconscious of their danger, on the very brink of hell. Athanasius was quickly summoned from his monastery and forced to withdraw his censure.

In this atmosphere of intrigue, ambition and hypocritical selfishness Irene of Montferrat developed her character. The Empire was tumbling into ruins, yet the one thought of the vast majority of its citizens, of all orders, was to obtain as much money as possible out of its shrinking treasury and close their eyes to its future. Even the Emperor, who looked as far ahead as the next generation, consulted only the future of his family. His eldest son was, apart from any question of merit or competency, to succeed him in the tarnished splendour of the Bucoleon palace. To ensure this Irene saw him stoop to the crime of barbarously imprisoning his brother, and the spectacle of the young prince, travelling everywhere among the Emperor’s baggage like a caged bear, would impress deeply on her young mind the first duty of man, as it was conceived in Constantinople. For her own part she would take care to secure her position and that of her children.

Irene was now a mature and very spirited young woman in her early twenties. She had great force of character, a keen and strong intelligence, and an unchallenged virtue. It was an age of general laxity of morals, as we shall realize, yet Irene is not assailed on that ground. But ambition for her children became her dominant quality, and, as it grew stronger and more280 imperious in face of obstacles, it warped her character, saddened her life, and made her career inglorious and futile. Had she been the first wife of Andronicus, she might have rendered very valuable service to the Empire; as it was, she became recklessly absorbed in her ambition, and only added to its formidable burdens. When, in 1296, Andronicus married his eldest son to Maria of Armenia, she began that sombre brooding on the inferior position of her own children which was to embitter the latter part of her life. The policy of Andronicus would be to make poor matches for her children; her policy was to prevent it.

We shall be glad to think that Irene had no voice in the first matrimonial settlement of one of her children—the marriage of Simonides to the King of Servia—for it was a sordid and abominable transaction, but she seems at least to have played her part in the ceremony without resentment. We had, in the last chapter, a glimpse of the condition of Servia in the thirteenth century. In the year 1298, which we have reached, there was on the throne a particularly objectionable type of “kral,” as the Servians called their ruler. He had first married the daughter of a neighbouring king, but he had led astray his brother’s wife, who was a sister of Anna of Hungary, and, when a third sister came on a visit to his Court, he conceived so violent a passion for her that he sent his wife home to her father. This lady was a nun, yet the Kral persuaded her to discard her black robe and go through a form of marriage with him. He then tired of the royal nun in turn, and married the daughter of King Terter of Bulgaria. By the year 1298 he was ready for a third change. None of his three queens had given him an heir to the throne, and he was therefore disposed to listen to the expostulations of his clergy and the advances of Andronicus.

At this time the Emperor’s sister Eudocia returned, a young and attractive widow, to the Court at Constantinople. She had married, and recently lost, the Emperor281 of Trebizond, and came home to enjoy her fortune in her native city. Andronicus pressed her to marry the Kral of Servia, whose army would be useful to him. When Eudocia indignantly refused, there was no lady of the imperial house to offer to the Kral except the little Simonides, who had not yet reached her seventh birthday. The only serious obstacle which Andronicus saw to the alliance was the fact that the Kral’s first wife still lived, and both the Servian and Byzantine clergy would regard the marriage as invalid. But this obstacle was opportunely, perhaps artificially, removed by the death of that lady, and the child of six summers was taken by Andronicus and Irene to the Servian capital—we notice the caged Constantine still among the Emperor’s luggage—and married to the middle-aged and hot-blooded barbarian.

Since we shall find Irene in the following year making a most violent and effective protest against the marriage of her eldest son, and do not find her making any protest at all in regard to the marriage of Simonides, we must conclude that she consented to this abominable procedure. The patriarch of Constantinople, who had been deceived by them, felt so strong a repugnance to the marriage that he followed the Emperor to Servia and vainly endeavoured to secure an audience. Irene seems to have given him no assistance. The husband proposed for her child was a king: the wife proposed for her son in the following year was not of royal birth. We see her ambition already corrupting her nature. She was content to stipulate that Simonides should be treated as a sister until she reached the condition of puberty, and entrusted her to the “honour” of the fiercely sensual and unscrupulous Kral; though we shall find in the course of time that Irene herself became largely responsible for the Kral’s breach of his engagement to respect the age of her daughter. Irene and Andronicus returned to Constantinople, bringing with them the Bulgarian princess whom Simonides had replaced.

This lady, it is interesting to note, was married soon afterwards to the Emperor’s brother-in-law, Michael Cutrules, who had wedded, and recently lost, Andronicus’s youngest sister. But her career ended in prison before many years, as Michael was convicted of treason and placed for life, with his wife, in one of the palace dungeons.

In the following year, 1299, Andronicus proposed to marry Irene’s eldest son, John, and the struggle of her life began. The wife chosen for him was a daughter of one of the chief ministers, Nicephorus Chumnus, and Irene now fought her husband with such vigour that he was compelled to desist. Andronicus wished to remove her children from any possible rivalry with his son Michael; Irene was determined that they should make royal matches and wear diadems. She had probably by this time conceived the ambitious idea which wrecked her life, and trusted to induce Andronicus to detach fragments of his Empire in which her sons might set up independent Courts. In this she was, no doubt, mainly inspired by ambition for her children, but the later course of the quarrel will show that she had secret personal grievances against her husband, and she may have contemplated retiring to the Court of one of her sons.

For five years Irene resisted the design of her husband and, with tears at one time and threats at another, urged her own scheme upon him. Andronicus became weary and irritated. The ecclesiastical quarrel still distracted his capital, the Turk ravaged his provinces, the pirate swept his seas, and a new burden was added to his cares. An army of Spaniards, who had been set free by the termination of the Twenty Years’ War in Italy, came eastward in search of adventure, and, being employed by Andronicus to fight the Turk, soon proved a very fertile source of anxiety and trouble.

In the midst of these harassing cares Andronicus impatiently resented the importunity of his wife, and their life became one of incessant quarrel. Irene threatened that she would not share his bed unless he either283 associated her sons in power with Michael or secured them independent kingdoms at his death; Andronicus retorted by locking his door against her, and Irene was further embittered. In 1304 her son John married Irene, the daughter of Chumnus, and the Empress went at once to live at Thessalonica. The chroniclers relate that Andronicus had at length persuaded his wife to consent to this marriage, but that seems to be a half-truth put forward by the Emperor. He gave John the government of Thessaly, and Irene accompanied him and the younger Irene to Thessalonica, where, as we saw, there had been a palace since the days of Boniface.

In the capital of the Greek province Irene now entered upon an activity that gave her husband more anxiety than ever. He presently learned that she was openly telling to the monks and matrons of her Court certain indelicate details of their conjugal life which “the most brazen courtesan would blush to tell,” says the chronicler. Through her daughter these details were forwarded to the Kral of Servia, but such matters were not of a nature to induce that monarch to declare war on his erring father-in-law. The Duke of Athens was then assailed by the ambitious Empress; he was urged to marry his daughter to her second son, Theodore, and then wrest the province of Thessaly from Andronicus. Irene’s plan was now clear. The most westerly part of the Empire was to be detached and converted into a kingdom for her and her children. The Duke of Athens declined to pit his small force against the Byzantine mercenaries, and Theodore was sent to Lombardy to wed the daughter of the Marquis Spinola, who held a small territory in the north of Italy. The marriage was spiteful, as Andronicus was not consulted, but it did not bring to Irene an alliance of any material value; and, as John died, childless, about the same time (1307), she turned again to the Kral of Servia.

Andronicus was alarmed. He was at the height of his trouble with the Catalans and at war with Bulgaria,284 so that fresh trouble with Servia would be a serious complication. He made every effort, short of granting her extreme demand, to conciliate Irene, but the passionate woman determined to profit by the Empire’s difficulties and carried on the war with a spirit and ability that deserved a better cause. She had taken with her to Thessaly a vast quantity of money and treasure, and she now employed this more persuasive argument on the Kral of Servia. She sent him a superb crown from the Byzantine treasury and some of the richly embroidered robes of the Byzantine Court for himself and her daughter; and she forwarded to him, the chronicler says, money enough “to equip and maintain a hundred triremes for ever.” It is unfortunate that we do not know more particulars about her departure from Constantinople and the way in which she became possessed of all this treasure. It looks as if she had been collecting resources for some years, and had left with a quite definite intention of fighting her husband. Her present policy was to induce the Kral to make war on Andronicus and take Constantinople. Her ambition had degenerated into a disease and a crime.

There is grave reason to blame Irene for another issue of her ambition which, no doubt, she did not intend. Next to the taking of Constantinople Irene most desired to see her daughter have a son to inherit the new Empire, and it is plain that she impressed this on the Servian monarch. Simonides was now fourteen or fifteen years old, and would be regarded in the East as a possible mother, but, whatever the details may be, the fact is recorded by the chroniclers that her womb was injured in some way and Irene was told that her daughter would never have children.

Her next plan was that the Kral should adopt one of her sons as his heir, and, as her treasury was ample, the Kral consented. Demetrius, her youngest son, was sent with a splendid escort and luxurious outfit to the Servian Court, but its rough ways disgusted the spoiled youth and he returned to his mother. As a last resource Irene recalled Theodore from Lombardy and sent him to Servia.

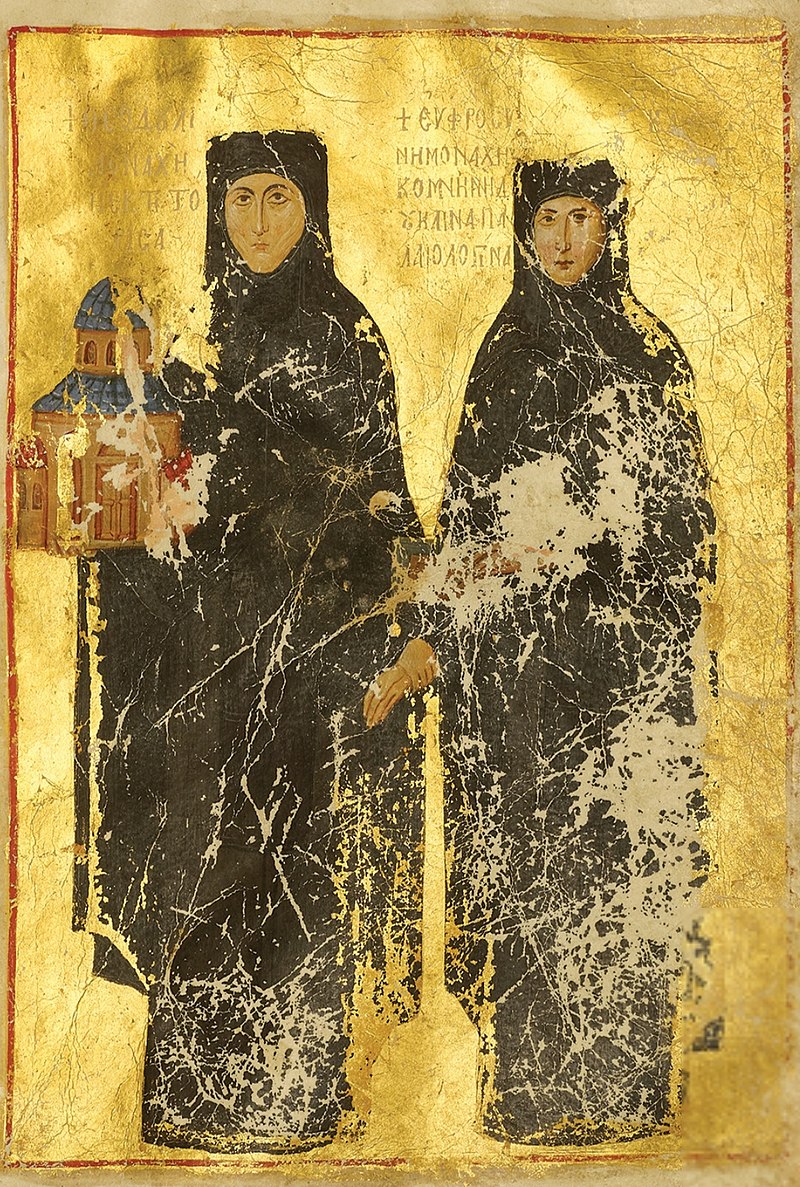

When Theodore also found the ways of the Servians unbearable, and returned to Lombardy, Irene’s fiery spirit was quenched. Her four years’ struggle for a kingdom had entirely failed, and her health was affected. She confessed her defeat and requested Andronicus to allow her to return to Constantinople. We are scarcely surprised that Andronicus refused permission, politely assuring her that, as the Turks now swarmed in the neighbourhood of Constantinople, she was safer at Thessalonica. Even when, in the following year, the Catalan troops returned to the West, and relieved him of one of his burdens, the Emperor gave her no invitation to return. She lived on for eight years in complete obscurity at Thessalonica, and died of fever at Drama, in Thessaly, where she had a country palace, in 1317, leaving, in spite of her great expenditure, a considerable fortune. The dead body of his fiery spouse was not feared by Andronicus. He permitted Simonides to bring it to the metropolis and inter it with imperial ceremonies among the royal graves.

When Theodore also found the ways of the Servians unbearable, and returned to Lombardy, Irene’s fiery spirit was quenched. Her four years’ struggle for a kingdom had entirely failed, and her health was affected. She confessed her defeat and requested Andronicus to allow her to return to Constantinople. We are scarcely surprised that Andronicus refused permission, politely assuring her that, as the Turks now swarmed in the neighbourhood of Constantinople, she was safer at Thessalonica. Even when, in the following year, the Catalan troops returned to the West, and relieved him of one of his burdens, the Emperor gave her no invitation to return. She lived on for eight years in complete obscurity at Thessalonica, and died of fever at Drama, in Thessaly, where she had a country palace, in 1317, leaving, in spite of her great expenditure, a considerable fortune. The dead body of his fiery spouse was not feared by Andronicus. He permitted Simonides to bring it to the metropolis and inter it with imperial ceremonies among the royal graves.

The further career of Simonides herself is not without interest, though we have no very definite portrait of the daughter of Irene and protégée of the Apostle Simon. Once in Constantinople, she declared that she would not return to the less luxurious Court and the rough manners of her husband. Andronicus did not interfere until, after a time, the Kral sent word that he would attack Constantinople if his wife did not return.

She was forced by the Emperor to join the Servian envoys, and set out with them for Belgrade. But Simonides had not a little of the spirit of her mother. When they had proceeded some two or three days’ journey toward Servia, she cut her hair and donned the black robe of a nun. The Kral’s servants were stupefied, and, thinking it better to anticipate the order of their monarch, drew their swords. With Simonides, however, was her half-brother Constantine, who saw a more reasonable solution of the difficulty. He stripped her of the monastic robe with his own hands, compelled her to put on her royal garments, and sent her to her Court. The Kral died a few years afterwards, and Simonides returned to live in Constantinople and find more congenial lovers, as we shall see, amongst its more refined nobility.

But the adventures of Irene’s daughter continue into the next reign, and it is time to turn back and consider the new Empress who had been crowned in Constantinople in 1296. Once more we shall find a story of a woman of excellent character, though less gifted than Irene, tainted by the Byzantine atmosphere and driven to assist in rending the dying Empire. Nothing but a strong infusion of virile moral feeling could have arrested the decay of the Empire. Unhappily, moral sentiment sinks lower and lower at Constantinople after the death of Irene, while the energetic Turk slowly advances to its destruction.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints