![]()

Nave and Aisles of Hagia Sophia

“It is against the precepts of our religion that such things should remain exposed on the walls of a place of worship; cover up the pictures carefully so that the plaster may be removed at any future period without injury to them, for God only knows the future, and He alone can tell for whom the building may be reserved.”

Sultan Abdul Medjid - 1845.

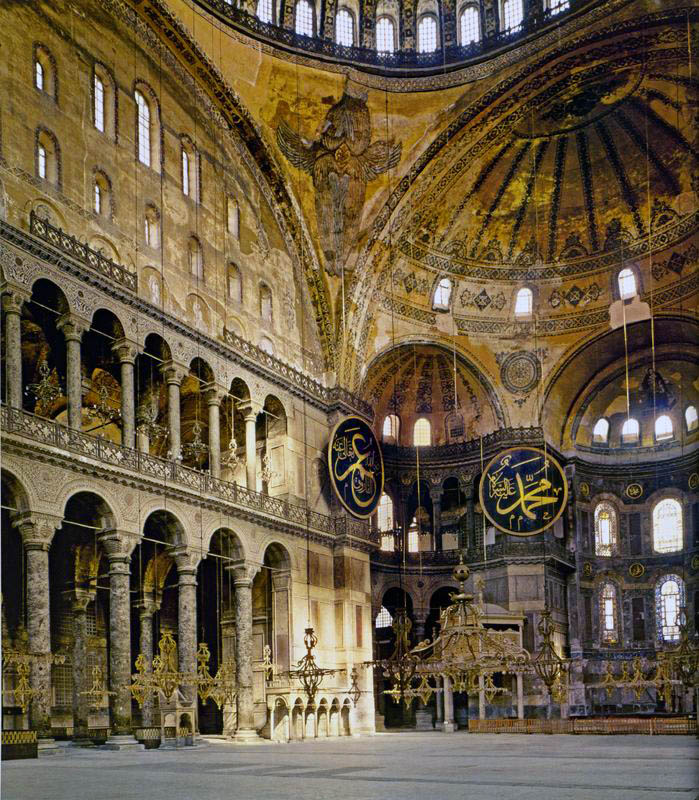

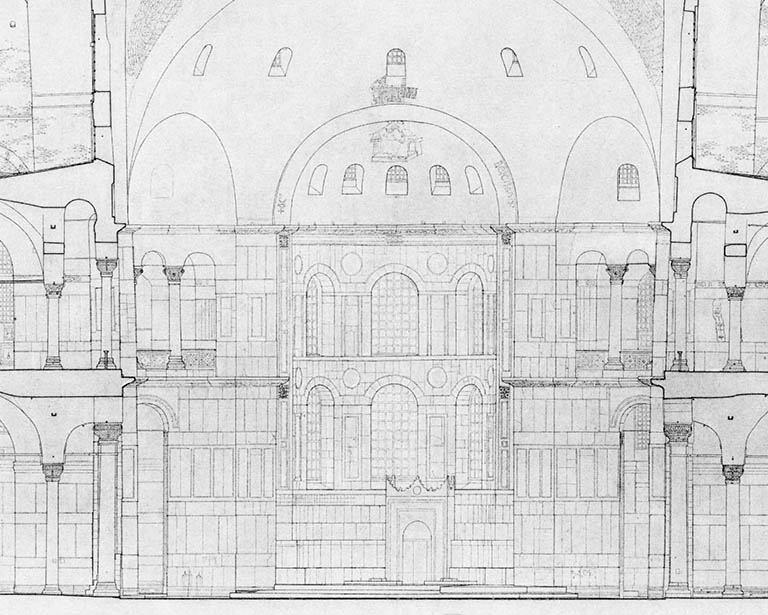

Above is a drawing of the nave of Hagia Sophia, you can clearly see how the sides have been pushed out by the pressure of the weight of the dome arches. You can see it becomes worse as you get closer to the dome. It is particularly apparent on the right (south) side where the columns of the gallery exhedra are really pushed out of alignment. One can also see how the tympana walls have been pushed outwards. Visitors to Hagia Sophia were alarmed to see titling columns in the galleries that looked like they would collapse in the next earthquake. In the 1850 restoration of Hagia Sophia the Fossatis reset a number of the worst ones. You can see the see marks in the floors were the bases used to set.

Above is a drawing of the nave of Hagia Sophia, you can clearly see how the sides have been pushed out by the pressure of the weight of the dome arches. You can see it becomes worse as you get closer to the dome. It is particularly apparent on the right (south) side where the columns of the gallery exhedra are really pushed out of alignment. One can also see how the tympana walls have been pushed outwards. Visitors to Hagia Sophia were alarmed to see titling columns in the galleries that looked like they would collapse in the next earthquake. In the 1850 restoration of Hagia Sophia the Fossatis reset a number of the worst ones. You can see the see marks in the floors were the bases used to set.

In plan Hagia Sophia closely approaches an exact square, being 235 ft. north and south, by 250 ft, east and west, exclusive of the narthex and apse. The nave of Hagia Sophia, 250 ft. in length, 100 ft. wide, and 179 ft. high, is dominated by its gigantic rows of green Verde Antico marble, towering arches and enormous dome. It was built as a domed basilica. The dome is 107 ft. across by 48 ft. in height and has 40 windows. The great arches supporting the dome are 100 ft. wide and 120 ft. tall.

Unfortunately the architecture and proportions of Hagia Sophia are intentionally marred by huge Arabic medallions with Islamic inscriptions that are Ottoman war trophies. They represent the names of God, the Prophet and his four Companions of, Abu-bekr, Omar, Osman, and Ali. From the date of the forced conversion of Hagia Sophia into mosque in 1453 until 1850 these plaques were small and square. During the restoration of Hagia Sophia by the Fossati brothers in 1850 these gigantic shields - the size of a small building - were added. Fortunately the Islamic shields were removed in the 1930 and the building was completely photographed. I have created a page of them so you can see Hagia Sophia as it was meant to be seen. We can be certain that they will remain for long time, as the current government of Turkey is run by Islamic religious fanatics. They see Hagia Sophia as a symbol of Islamic triumph over Christianity and the West.

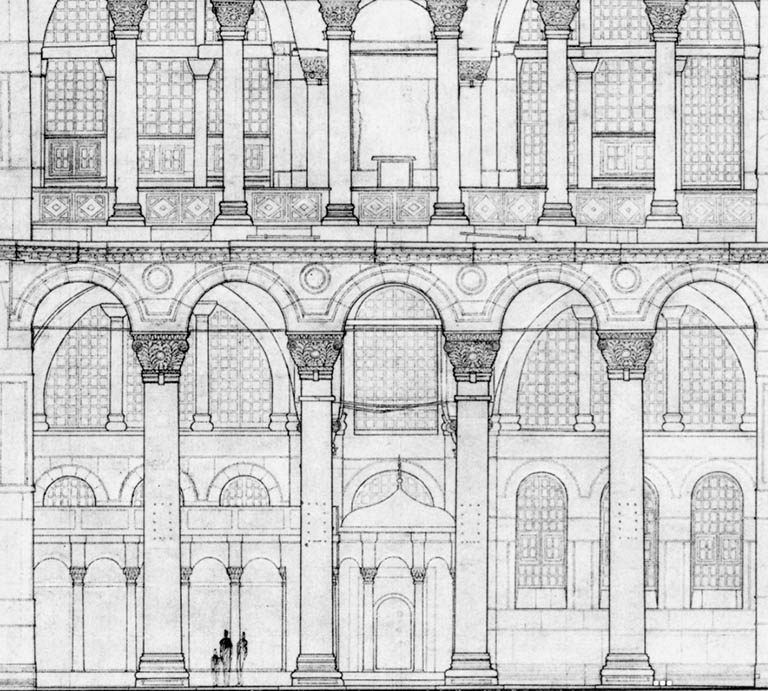

Above is a drawing of the nave arcade by van Nice. Look at the size of the people to get an idea of the scale. The square-shaped markings on the lower columns are the remains of icons that were attached to them. Originally the top colonnade in the gallery was designed to have the same sized columns as the lower one. After the piers began to distort during the building process it was decided to use smaller columns that weighed less. When the number changed from 4 to 6 it was no longer possible to align them. The distortions also made the builders change the alignment of the tympana. Is is thought that Basil I may have rebuilt the tympana in the 9th century after an earthquake damaged them and cracks appeared in the western semi-dome. He also had the tympana and the western semi-dome redecorated with mosaics after repairing them.

Above is a drawing of the nave arcade by van Nice. Look at the size of the people to get an idea of the scale. The square-shaped markings on the lower columns are the remains of icons that were attached to them. Originally the top colonnade in the gallery was designed to have the same sized columns as the lower one. After the piers began to distort during the building process it was decided to use smaller columns that weighed less. When the number changed from 4 to 6 it was no longer possible to align them. The distortions also made the builders change the alignment of the tympana. Is is thought that Basil I may have rebuilt the tympana in the 9th century after an earthquake damaged them and cracks appeared in the western semi-dome. He also had the tympana and the western semi-dome redecorated with mosaics after repairing them.

When the church was built, after building the foundations the ground floor colonnades and bottom parts of the walls were erected. When the great arches were being built it was noticed that the pressure of their weight was pushing outward. This was caused not only by the weight of the brick and stone. As the mortar and brickwork dried out it became distorted. This meant that many changes had to be made to the design to stabilize the building. Extra columns and bracing arches were added to the ground floor. The size of the arches were widened and windows were eliminated from the tympana. On the gallery level the columns used were smaller and their were more of them. The distortion of the north and south walls is not so apparent from inside the building, but the lean is pronounced as you get to the level of the dome. The dome we now see is the second one that was repaired in 998 and 1346. These repairs - especially the 14th century one - have distorted the dome and one of the pendentives. The dome now has a bulge in it and the join between the 14th century repairs and the 6th century building created a curved disconnection between the older and newer work. All of these defects were less obvious before the advent of stark artificial lighting was installed. You can learn more about the dome by reading this page that is dedicated to it.

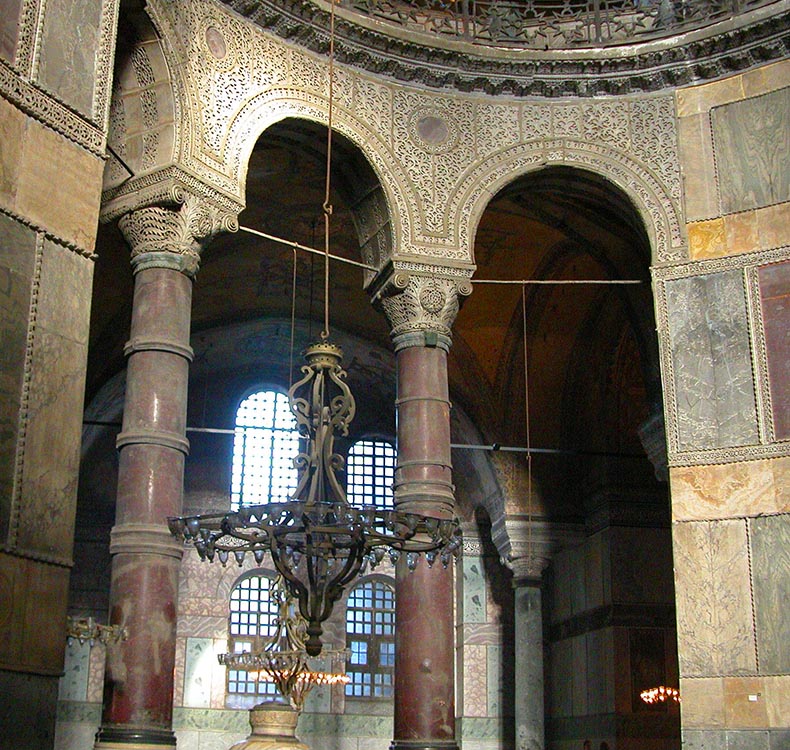

Above, Verde Antico columns in Hagia Sophia. You can see how the columns have been polished at ground level by millions of hands rubbing the surface. Formerly they were polished with hot wax. Some of the panels of Verde Antico marble in Hagia Sophia have decayed and lost a great deal of color as their surface degrades into talc. To stop this process is one of the urgent needs of Hagia Sophia. Fosatti straightened 13 columns in the galleries that appeared alarmingly out of line - they had been in the position for 800 years without a collapse, so the straightening would have been cosmetic.

Above, Verde Antico columns in Hagia Sophia. You can see how the columns have been polished at ground level by millions of hands rubbing the surface. Formerly they were polished with hot wax. Some of the panels of Verde Antico marble in Hagia Sophia have decayed and lost a great deal of color as their surface degrades into talc. To stop this process is one of the urgent needs of Hagia Sophia. Fosatti straightened 13 columns in the galleries that appeared alarmingly out of line - they had been in the position for 800 years without a collapse, so the straightening would have been cosmetic. Above, red Porphyry columns in Hagia Sophia. The porphyry columns of the western exedras have a total height of thirty-one feet ; the shafts are twenty-four feet and three-quarters long, and the diameter at the bottom is three feet one inch. The capital is four feet high, and the abacus above measures towards the nave four feet nine inches, and towards the aisles four feet eleven inches. In the direction of the thickness of the arch the side of the abacus measures five feet, the variation being due to the circular plan of exedras. In Byzantine times these columns were kept so brightly polished that you could see your reflection in them. The white marble capitals, arcade decoration, cornices and molding between the marble revetment were gilded. The marble revetment is dirty and dulled, the colors used to be much brighter. They were originally polished with hot wax.

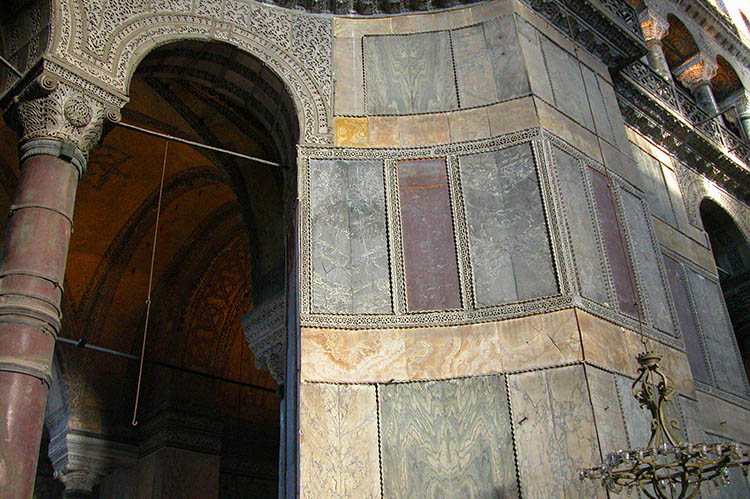

Above, red Porphyry columns in Hagia Sophia. The porphyry columns of the western exedras have a total height of thirty-one feet ; the shafts are twenty-four feet and three-quarters long, and the diameter at the bottom is three feet one inch. The capital is four feet high, and the abacus above measures towards the nave four feet nine inches, and towards the aisles four feet eleven inches. In the direction of the thickness of the arch the side of the abacus measures five feet, the variation being due to the circular plan of exedras. In Byzantine times these columns were kept so brightly polished that you could see your reflection in them. The white marble capitals, arcade decoration, cornices and molding between the marble revetment were gilded. The marble revetment is dirty and dulled, the colors used to be much brighter. They were originally polished with hot wax.

The marble revetment is fixed to the wall with a dark brown resin. In the beautiful opus sectile friezes, pieces of colored marble about a quarter of an inch thick were cut to the forms of the design, and then laid their polished faces downward at the bottom of a mold; on this was poured a three-quarter inch backing of resin mixed with bits of stone and brick. When set, the slabs so formed were attached to the wall with cement. The large marble slabs are one to two inches thick, and, besides the cement, are fastened to the walls by iron clamps.

There are a total of 107 columns in the church, 40 on the ground floor and 67 in the galleries. The giant Verde Antique columns on the ground floor of the nave are 34 ft tall including capitals and bases. These monoliths vary in diameter up to seven inches. They are the largest columns ever quarried in this stone. The shafts themselves are 28 ft tall. The Verde Antique columns in the galleries come in two sizes, 16 and 15 ft tall. There are eight columns in red Porphyry in the exhedra. Porfido rosso antico were quarried by slaves at Gebel Dokhan (the ancient Mons Porphyrites) in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. The quarries stopped production in the fifth century and these columns were reused or came from existing stock. They vary in size from 24 to 25 feet tall, and the bases are of different heights to fit the column. The columns are set into soft lead blanks at their bases and have bronze or leaded brass bands. This prevents earthquake damage. The bands were gilded. I have read that the columns are not all monoliths, but have been assembled in pieces and that some of the collars mark these joints. One is fractured. In Byzantine times the capitals and cornices were painted blue and gilded. You can read about the columns of Hagia Sophia by visiting this page.

The band of yellow onyx is especially beautiful. It is composed of Alabastro fiorito, from the Pamukkale area in Denizli, Turkey. This onyx is actually a banded travertine. Pamukkale is the site of the ancient city of Hierapolis, and travertine, deposited by hot springs, forms huge terraces from which stone was extracted in ancient times, and is still quarried to this day. Ancient quarries have been located near the ruins of Hierapolis and near the village of Gölemezli.

The band of yellow onyx is especially beautiful. It is composed of Alabastro fiorito, from the Pamukkale area in Denizli, Turkey. This onyx is actually a banded travertine. Pamukkale is the site of the ancient city of Hierapolis, and travertine, deposited by hot springs, forms huge terraces from which stone was extracted in ancient times, and is still quarried to this day. Ancient quarries have been located near the ruins of Hierapolis and near the village of Gölemezli.

The rare and exotic marble revetment of the church - which was assembled from all over the Roman world - was considered the greatest glory of its original decoration. The marble blocks were assembled on the building site, sawed into panels, polished and then mounted onto the walls with clamps and mortar. Every stone was different and had factors that had an effect on how it was cut and mounted. Some stones were harder than others to cut while others were more difficult to polish. For example, Verde Antique is composed of elements that are both hard and soft; when you polish it it comes out somewhat lumpy. The builders had to wait until the stone and brickwork were fully dry before mounting the revetment. Even though it's a marble veneer mounted on a flat surface some stones were better suited for the job than others. Some stones - like Verde Antico - were compact and reliable, while others, like onyx, were subject to fracturing and flaking. During Ottoman times large sections of the marble revetment was removed and used in other building projects or sold. It was replaced with painted plaster, which looks horrible. Today only 60% of Hagia Sophia still has its revetment. Learn more here.

In the north aisle is the famous column of Saint Gregory which every visitor touches when they visit the church, In the year 1200 Anthony of Novgorod described how it was done then:

In the north aisle is the famous column of Saint Gregory which every visitor touches when they visit the church, In the year 1200 Anthony of Novgorod described how it was done then:

"When one turns towards the gate one sees at the side the column of S. Gregory the Miracle-Worker, all covered with bronze plates. S. Gregory appeared near this column, and the people kiss it, and rub their breasts and shoulders against it to be cured of their pains ; there is also the image of S. Gregory. On his feast day the patriarch brings his relics to this column. And there placed above a platform is a great figure of the Savior in mosaic; it lacks the little finger of the right hand When it was finished, the artist looked at it and said, "Lord, I have made thee as if alive." Then a voice coming from the picture said, "When hast thou seen me?" The artist was struck dumb and died, and the finger was not finished, but was made in silver-gilt."

On the second floor of Hagia Sophia are three galleries. The one on the right - the South Gallery - was reserved for the Imperial family and the clergy of the church. The Patriarch would address the crowds of people in the nave from this gallery, which was richly decorated with mosaics. The North Gallery was used by women during services, but was open to both men and women at other times. It was also decorated with mosaics. In the center of the West Gallery, overlooking the nave, was a special location for the Empress and her women. This area was also used to display the treasures of Hagia Sophia and the Imperial regalia at Easter, when it was shown to the public. The columns of the galleries were hung with silk and transparent linen drapery. In 1907 it was reported that the galleries were usually closed because of the danger of falling plaster and mosaics and only the NW ramp was open. They also said you could make out the outline of the Virgin and Child in the apse.

On one of the piers of the nave, in the S.E. bay, is a mark, resembling the imprint of a bloody hand, that is said to indicate the height to which the the the Conqueror was able to reach as be rode over the Christian corpses in the church. In the South Gallery is a closed door leading to a small chapel in one of the buttresses, which communicated with the Baptistery by means of staircases and passages. This chapel, which was rediscovered by the Fossatis, is supposed to be that into which, according to tradition, a Christian priest fled with the sacred elements when interrupted in his service by the entry of the Turks into the church. He is expected to issue from his hiding-place and resume his functions when the mosque again becomes a Christian sanctuary. This chapel, which has been the object of so much speculation, has recently been investigated thoroughly by Ken Dark and is described in his new book on Hagia Sophia.

In Byzantine times the vaults were covered with plain gold mosaics. In Justinian's building the mystical presence of God was created through dramatic shafts of light that poured into the church and moved around the church based on the time and day of the year. There were no figures in the decoration that church was decorated by vast fields of gold mosaic that reflected light throughout the nave and into the side-aisles. Justinian's main architects were not Christian and intentionally designed the church to express the "Wisdom" of the Godhead using light in a metaphysical way. None of his can be seen today when the artificial lighting system is switched on.

In Byzantine times the vaults were covered with plain gold mosaics. In Justinian's building the mystical presence of God was created through dramatic shafts of light that poured into the church and moved around the church based on the time and day of the year. There were no figures in the decoration that church was decorated by vast fields of gold mosaic that reflected light throughout the nave and into the side-aisles. Justinian's main architects were not Christian and intentionally designed the church to express the "Wisdom" of the Godhead using light in a metaphysical way. None of his can be seen today when the artificial lighting system is switched on.

The seraphim angels in the eastern pendentives date from the 1347 rebuilding of the great eastern arch, the eastern part of the dome and vaults. They are each unique in the design of their wings. There is no explanation for the difference between the wings which must be intentional. The south (right facing the apse) seraphim's wings are much thicker (shall we say less elegant?) - than the other. It has more feathers and the colors are reversed. The wings on the top are open - not crossed like the left one. It would be interesting to know which one was first and if two different artists were involved. The mosaic seraphim in the western pendentives have vanished. They must have disappeared before 1710 because Loos does not include them in his drawings of that time. However, Antoniades reports that considerable fragments of the western seraphim were still visible in 1894 when he saw them. After the earthquake these traces were destroyed in the reconstruction works. When they were covered over by the Fosattis they were painted in new horrible, clunky designs in flat oil paints and new 'gothic-style' ornaments were added. They are obviously supposed to be copies of the eastern seraphim. If so, they are dreadful copies. Perhaps their workers were unsupervised when they created them. The contrast between the Byzantine and Ottoman seraphim is so obvious that this must have been apparent when they were unveiled. There is no way those heavy Ottoman seraphim (the Ottomans thought they were bats) could have flown! We know the western arch was completely replastered after the 1894 earthquake and all of the surviving mosaics there (Virgin and Child and two saints, Peter and Paul) were were destroyed. The objective of the restoration was not to preserve the Christian art of old Byzantium, but to return Hagia Sophia to service as a mosque as soon as possible. The painted seraphim we see there must date post-1894. We can easily tell the difference between Fosatti plaster which is painted a horrible dark mustard - and plaster from 1894+ which is bright yellow-orange. Perhaps the artists who painted them thought they were supposed to create images of bats!

At the bottom of the picture you can see iron brackets that used to hold glass lamps. The wooden balcony railings for lamplighters surrounding the cornices are are Ottoman.

Here you can see the green marble bands and the square "omphalos" of colored marbles and mosaic in the middle of the nave floor. Notice how the white marble floor slabs have been set in patterns of waves, to imitate the sea.

One of the most significant changes to Hagia Sophia was the removal of the ambo and solea, chancel screen and the altar including a giant columned ciborium over the altar. All of this was swept away when the church was converted into a mosque, all of the icons were smashed and the gospels were burned. All of the sacred treasures like the chalices and patens used in the liturgy were broken up and melted down. All that remains are two mosaics in the apse, one of the Virgin and Child and the other of an Archangel. In the bema arch are the ghostly traces of other mosaics but up during the 14th century - only their setting beds remain. Anthony of Novgorod who visited Hagia Sophia in 1200 described the altar:

"Above the great altar in the middle is hung the crown of the Emperor Constantine, set with precious stones and pearls. Below it is a golden cross, which overhangs a golden dove. The crowns of the other emperors are hung around the ciborium, which is entirely made of silver and gold. Thus the altar pillars and the sanctuary and the bema are built of gold and silver, ingeniously made, and very costly.... How magnificent are the gold and silver chalices, garnished with precious stones and pearls when the splendid chest, called Jerusalem, is brought out with the flabella, there rises amongst the people a great groaning and weeping but here is a wonderful miracle, which we saw in S. Sophia. Behind the altar of the larger sanctuary is a gold cross, higher than two men, set with precious stones and pearls. There hangs before it another gold cross a cubit and a half long, with three gold lamps, which hang from as many gold arms (the fourth is now lost). These lamps, the arms or branches, and the cross, were made by the great Emperor Justinian who built S. Sophia. By virtue of the Holy Spirit the small cross with the lamps ascended above the big cross, and again slowly came down again without going out. This miracle took place after matins, before the commencement of the mass : the priests who were in the sanctuary saw it, and ail the people in the church who saw it cried with fear and joy, "God in His mercy has visited us.'". This great and wonderful miracle was wrought by God in the year 6708 on Sunday, May 21st being the Commemoration of S. Constantine and his mother Helena, during the reign of the Emperor Alexius and the patriarchate of John. It was on the feast of the 318 fathers."

You can learn more about the sanctuary by clicking here.

Above are two reconstructions of Hagia Sophia showing the chancel screen, ciborium and ambo. Notice how bright it looks with the solid gold fields of mosaic!

The nave is dominated by four great mosaic Seraphim with six wings in the pendentives. Two still survive. Each head is four feet two inches high. The upper feathers of the wings are a light green, and the under feathers brown. In the dome was a famous mosaic of Christ Pantokrator which was probably scraped off in the middle of the 18th century. The tympana was decorated with prophets, bishops and angels, of which a few survive. The western semi-dome had images of Peter and Paul along with a Virgin and Child. Most of the vaults of the nave were filled with plain gold mosaic. Visitors to the church remarked on how beautiful the masses of gold mosaic looked and how the sparkling light charged the air in the nave. The horrible painted ornaments were added in the 19th century during the Fossati redecoration.

The nave is dominated by four great mosaic Seraphim with six wings in the pendentives. Two still survive. Each head is four feet two inches high. The upper feathers of the wings are a light green, and the under feathers brown. In the dome was a famous mosaic of Christ Pantokrator which was probably scraped off in the middle of the 18th century. The tympana was decorated with prophets, bishops and angels, of which a few survive. The western semi-dome had images of Peter and Paul along with a Virgin and Child. Most of the vaults of the nave were filled with plain gold mosaic. Visitors to the church remarked on how beautiful the masses of gold mosaic looked and how the sparkling light charged the air in the nave. The horrible painted ornaments were added in the 19th century during the Fossati redecoration.

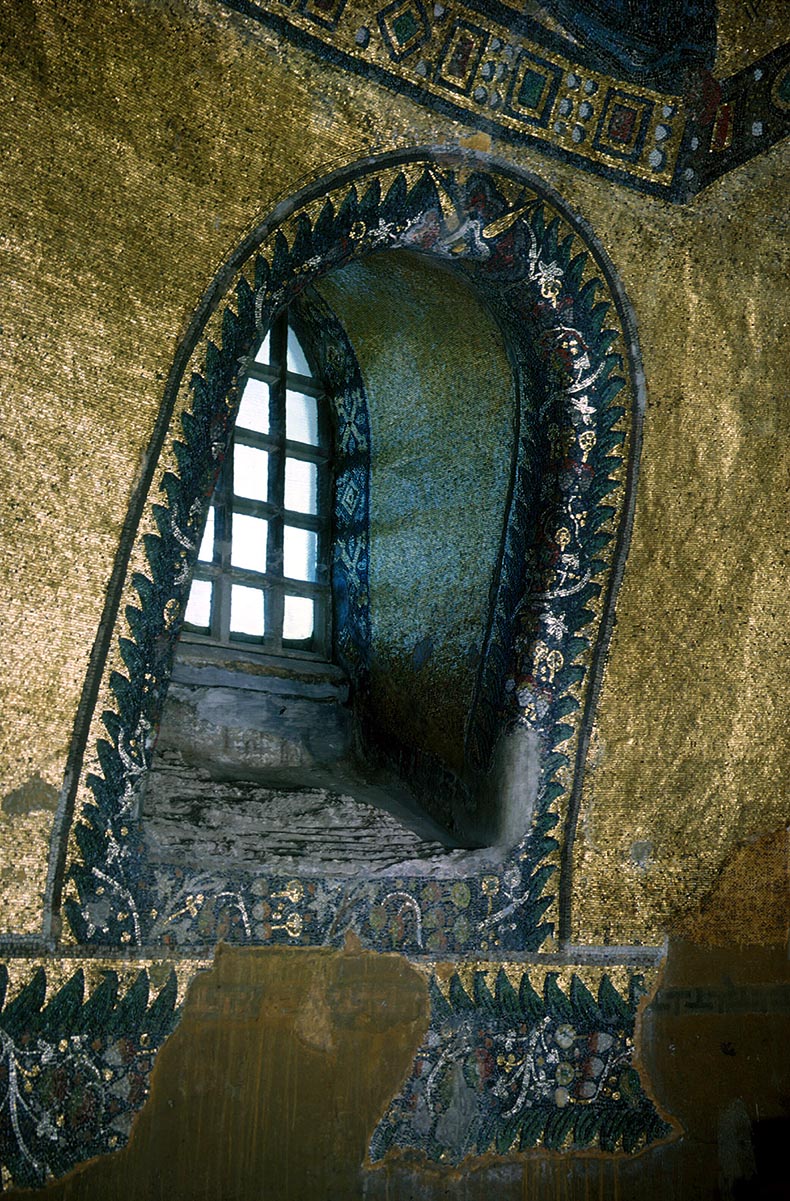

On the right is a drawing of a marble window frame from the church. The frame is carved with a meander pattern. The panes were set with large glass panels. Some windows had translucent stone panes. one still survives in the Western Gallery. During Ottoman times many of panes were replaced by round bottle glass set in plaster, but this was never done before 1453. It seems that there was also some stained glass in the church. Fragments have been found in the past.

On the right is a drawing of a marble window frame from the church. The frame is carved with a meander pattern. The panes were set with large glass panels. Some windows had translucent stone panes. one still survives in the Western Gallery. During Ottoman times many of panes were replaced by round bottle glass set in plaster, but this was never done before 1453. It seems that there was also some stained glass in the church. Fragments have been found in the past.

Hagia Sophia was built to take advantage of natural lighting. The lighting of the church is most brilliant ; wherever space or construction permitted, windows of considerable size were opened, so that light floods the whole church. At the foot of the dome the light streams in through forty windows, and each of the seven apses has five openings. The eastern sun sends its first rays through the six windows in the apse, and the setting sun shines through the great west lunette. There arc twenty-four windows in me two great tympana, besides large windows in the aisles. The windows were set to specifically light various parts of the church during the daily hours of services and liturgies. The light was also planned to fit the solar calendar and changed by the dates of special feasts. There were thousands of glass lamps set in hundreds of silver chandeliers throughout the church which burned olive oil. The cost of lighting the church limited the number of services that could be held in the church. Several emperors made special allotments of money so that daily mass could be held there, but this had to be halted when money ran short. Candles were also in processions and lit in front of icons. Many of them were decorated with elaborate designs and colors. Hagia Sophia produced its own bees wax candles and sold them to visitors. They came in all sizes and prices so that anyone could afford them. The church also operated candle shops in the city.

There was the regular 'miracle' in the sanctuary when a great cross-shaped chandelier mysteriously lifted up into the air without extinguishing the lights that Anthony of Novgorod described earlier. The miracle of the moving cross of lights mentioned by Anthony reminds us of a remarkable custom in regard to the great coronas of lights in Byzantine churches which is observed on Mount Athos, and also at Sinai, and is probably ancient. A part of the great festival service at the Vatopedi Montastery on Athos consists in singing the Polyeleos. When the last of the multitude of candles had been lighted in the great coronas under the domes, the monks fetched long poles, with which they pushed out the candelabra to the frill extent that their suspending chains permitted and then let them go, the result being that in a few minutes the whole church was filled with slowly swinging lights. Thus the chandeliers in the church were made to rotate and sway which created beautiful star-like effects in the darkened church. One can imagine nighttime and vespers services in Hagia Sophia were quite magical when combined with choirs, icons, golden mosaics and beautiful polished marbles.

Today the church has huge heavy wooden chandeliers throughout the nave. They are Ottoman and date from 1845. Up to the time of Fossati's restoration there was an immense polygon of probably some sixty feet diameter of iron rods suspended from the dome. Grelot described it in 1680 as a large circle of iron rods hanging down to within eight or ten feet of the pavement and having fixed to it "a prodigious number of lamps, ostrich eggs, and other baubles." The Fosatti wooden chandeliers have been wired for electricity with heavy cables. The nave has been set up with a new lighting system that is not appropriate and fails to provide a natural or historically accurate setting. Recent studies have indicated that natural light is the best way to light Hagia Sophia during the day. I have a special page on the lighting of Hagia Sophia and you can read it here. You can also learn more about the chandeliers and lighting of the sanctuary here.

On the floor of Hagia Sophia are hundreds of beautiful white paving slabs in Proconnesian marble. They are patterned with gray waves and set in book-matched bands. Across the floor are green 'rivers' - bands of Verde Antico marble which indicate various points in the processions that crossed Hagia Sophia during services.

On the floor of Hagia Sophia are hundreds of beautiful white paving slabs in Proconnesian marble. They are patterned with gray waves and set in book-matched bands. Across the floor are green 'rivers' - bands of Verde Antico marble which indicate various points in the processions that crossed Hagia Sophia during services.

On the south side, towards the sanctuary is a huge square of colored slabs of marble called the omphalos (or omphallion), meaning navel in Greek - opus sectile is the technical term for this type of work - it is eccentrically laid. It was probably put here by Basil I (867-886) during his 9th century refurbishment of the church. There are 29 rotae - circular plaques - of different marbles of various sizes in it. The kinds of marbles employed for the bigger rotae and the number used are: grey Granite (1), red Porphyry from Egypt (5), green Porphyry from Sparta (1), Sagarian (3), Verde Antico green from Larissa in Thessaly (3), black-and-white from Aquitania in France (1), pink Granite (1), for the lesser rotae: Marmor Iassensis (4), green Porphyry (5), Verde Antico green (4),and red Porphyry (3). All of the rota are surrounded by bands of white Proconnesian marble.

In the center is a gigantic circle of gray granite - 10.5 feet in diameter - which marks the spot where the Emperor's throne stood. The Emperor was not crowned here, that took place on the now vanished ambo in the center of the church. The omphalos has been repaired and reorganized. The huge gray disk may have originally been in red Porphyry that was damaged when the the vault fell in 1346 and had to be replaced. Anthony of Novgorod says the original disc was made of red Porphyry when he saw it. Porphyry is hard but brittle. It was usually cut thinly because of its rarity. Both of these factors would mean the big rota of Porphyry could have been broken beyond repair. As no huge Porphyry disk of this size could be found in the 14th century it was replaced with grey granite. The 1346 repair probably mixed up other elements which confused the layout. When Hagia Sophia functioned as a church the omphalos was surrounded with a brass railing. In Ottoman times it was covered with a layer of mortar and then concealed with rugs. When the omphalos was uncovered in 1935 the removal of the mortar covering it dislodged a lot of the mosaic which was not repaired properly. It was filed in with loose tesserae and cement. Today the railing has been replaced with a new one.

There is another circle of red Porphyry (shown below) to the south and right of the omphalos that marks another location were the Emperor stood or sat during services. It's exact use is unknown. The fact that is made of red Porphyry means it must have some Imperial purpose.

Above is an image of the Omphalos. The large circle is made of red Porphyry from Egypt, above it to the left is a disc of green Porphyry from Sparta in Greece, to the right of it is a small disc of green Verde Antique from Thessaly also in Greece. The white bands are white Proconnesian marble from Turkey. A band of Verde Antique surrounds the opus sectile square. It was said one night the Theotokos appeared to a priest to the right of the Omphalos praying to her Son, interceding for all Christians. Above this spot was hung a huge icon of the Russian saints Boris and Gleb, an icon that was frequently copied for Russian pilgrims.

Across the upper part of the nave are wide bands of beautiful and precious colored marble panels which mark the location of the chancel screen and altar of the church. There is a wide raised marble platform that marks off the sanctuary area. In Ottoman times this platform was cut back at an angle to indicate the direction of Mecca. In this period the marble floor was not visible, it was covered with Muslim prayer rugs.

In the far corner of the south aisle is the location of the Chapel of the Holy Well and the location of Imperial Metatorium or changing room. The far eastern end of the north aisle - where the Sultan's Box now stands, was used by the clergy as a staging area for services. It was very close to the the treasury of the church, which predated Justinian's church and is located outside the northeast corner of the church.

Pilgrims entered Hagia Sophia through the far left door of the inner narthex and moved clockwise through the church starting with the north aisle. The aisles were full of relics and dozens of huge icons, painted and created in mosaic. The walls were also set with hundreds of smaller icons and crosses that were set into marble revetment, columns and bases. The aisles had many altars and stands where pilgrims left candles. All of this is now gone.

Singers and choirs in the church were centered around the ambo in the center of Hagia Sophia. On special occasions singers would climb into the dome and chant like angels from heaven. There were both male and female singers. You can try the acoustics of Hagia Sophia next time you are there - clap and sing something under the dome. You can do it right where the ambo was.

Before leaving the church turn towards the Royal Doors in the western wall of the nave and see the beautiful marbles here. There is some beautiful opus sectile work here of dolphins and a panel of a ciborium with a cross in it. Right in the center of of the walls a huge panel of Verde Antico where a famous mosaic of Christ of the Chalke once stood. It was lit by a famous miraculous hanging glass lamp, which was said to have fallen here from a great height to the marble floor without breaking. This is where a pilgrim would recite their last prayer to Christ before leaving the nave and a fitting place to end this page.

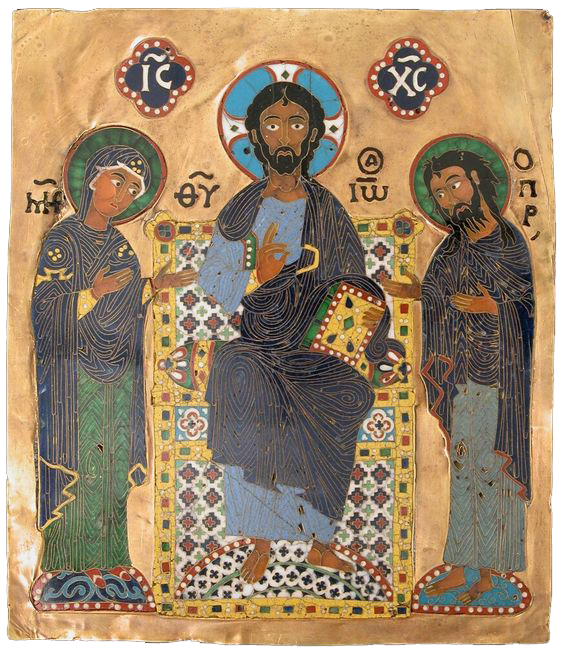

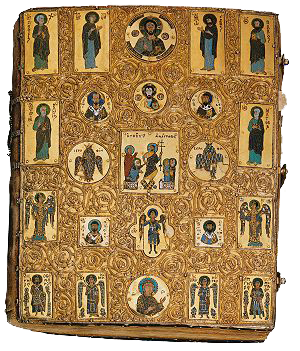

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints