By Niketas Chonates from O City of Byzantium

THUS Alexios, driven away by no one, rode on to Develton. It is grievous for a wife and beloved consort to do harm instead of providing assistance, according to the maxim of an emperor who suffered greatly because of the advice of a female chamberlain. But being a womanishman, it was a troublous matter and the worst thing possible, for what order given by him, even though leading to grief and extreme danger, would not command obedience? This indeed clashed with the interests of the Romans who were ill-fated to have effete and dissolute emperors who pursued a life of pleasure. Deeming it difficult to overpower necessity, they found their fear for their own lives altogether intolerable. But Alexios traveled the road he had chosen; the people in the palace of Blachernai viewed Alexios's escape as exceedingly insufferable and were thrown into a state of confusion and consternation because of the impending disaster, for they believed that there was nothing and no one to put off and check the Latins who were encamped nearby from making an imminent armed assault against the City and penetrating inside the walls. Supposing Alexios's kinsmen and his close friends, and even Empress Euphrosyne, to be guilty of treason, they did not offer them the throne; but because they could not resist, the savage sweep of events, they turned to Isaakios, Alexios's brother, and they who were being buffeted by tempestuous waves saw in him who was incarcerated within the palace their last hope. When the eunuch Constantine [Philoxenites], the minister of the imperial treasuries, had assembled the ax-bearers and discussed with them what needed to be done and was assured of the support of a faction that agreed that Isaakios should quickly assume the reins of em- pire, he had Empress Euphrosyne seized, her relations were taken prisoners, and Isaakios proclaimed emperor [17-18 July 1203]. He who had been blinded was ordained to oversee all things and was led by the hand to ascend the imperial throne.

Isaakios immediately dispatched messengers to his son Alexios and to the chiefs of the Latin host [18 July 1203] to inform them of the flight of his brother and emperor. They, however, made no changes in their expectations of the City; neither would they send Isaakios's son to him as requested by his father before Isaakios agreed to fulfill all the promises Alexios had made them. These were, as related earlier, that none of the extravagant pledges to provide the Latins with glory and gain was to be held back. Doing everything to insure against failure in ascending the paternal throne, Alexios, a witless lad ignorant of affairs of state, neither comprehended any of the issues at stake nor reflected for a moment on the Roman-hating temperament of the Latins. Having purchased his entrance into the City by the overturn of the imperial majesty, he was deemed worthy to sit on the throne with his father as co-emperor. The entire citizenry, therefore, ran in a body to the palace in order to behold the son with his father and to pay homage to both.

Not many days later [between 19 July and 1 August 1203], the Latin chiefs presented themselves at the palace together with their distinguished nobility."" Benches were set before them, and they all sat in council with the emperors, hearing themselves acclaimed as benefactors and saviors and receiving every other noble appelation for having honored the power-loving Alexios in his childish actions, and, moreover, for coming to his and his father's aid in their time of adversity. In addition, they enjoyed every kindness and courtesy. Amusements and dainties were contrived for them, for Isaakios, taking possession of what little was in the imperial treasury and taking into custody Empress Euphrosyne and her kinsmen, whom he robbed with both hands, lavishly bestowed the monies on the Latins.

But since the recipients considered the sum to be but a drop (for no nation loves money more than this race nor is there any more ravenous and anxious to run to a banquet) and were ever thirsting after libations as copious as the Tyrrhenian Sea, in utter violation of the law, he touched the untouchable, whence, I think, the Roman state was totally subverted and disappeared. Because money was lacking, he raided the sacred temples. It was a sight to behold: the holy icons of Christ consigned to the flames after being hacked to pieces with axes and cast down, their adornments carelessly and unsparingly removed by force, and the revered and all-hallowed vessels seized from the churches with utter indifference and melted down and given over to the enemy troops as common silver and gold. The emperor himself was in no way incensed by this raging madness against the saints, and no one protested out of reverence. In our silence, not to say callousness, we differed in no way from those madmen, and because we were responsible, we both suffered and beheld the most calamitous of evils.

The city rabble, not proceeding of its own accord on a laudable course of action, or following the advice of others to do what was best, since the enemy had already poured over the Roman provinces, senselessly razed and reduced to ashes the dwellings of the Western nations situated near the sea, making no distinction between friend and foe. Not only were the Amalfitans, who had been nurtured in Roman customs, disgusted by this wickedness and recklessness but so also the Pisans who had chosen to make Constantinople their home. As soon as Emperor Alexios was seen to flee, these nations fed on high hopes that mitigated much of their grief. By taking flight and being succeeded as emperor by Isaakios, Alexios reconciled the Pisans with the Venetians, having contrived even this against us; sailing across the Peraia where the enemy was encamped, they shared tent and table with their former adversaries, and with one mind they agreed on all things.

On the nineteenth day of the month of August in the sixth indication of the year 6711 [1203],147 certain Frenchmen (of old they were called Flemings), Pisans, and Venetians sailed with a company of men across the straits, confident that the monies of the Saracens were a windfall and treasure trove waiting to be taken. This evil battalion put into the City on fishing boats (for there was no one whatsoever to resist their sailing in and out of the City) and without warning fell upon the synagogue of the Agarenes called Mitaton in popular speech; with drawn swords they plundered its possessions. As these outrages were being committed senselessly and beyond every expectation, the Saracens defended them- selves by grabbing whatever weapon was at hand; aroused by the tumult, the Romans came running to their assistance. Not as many arrived as should have, but soon, after fighting on the side of these men, the Latins were compelled to withdraw. The latter abandoned hope of resisting with weapons and learned from experience the use of fire; they proposed to resort to fire as the most effective defense and the quickest course of action to subdue the City.

And, indeed, after taking up positions in a goodly number of locations, they set fire to the buildings. The flames rose unbelievably high above the ground throughout that night, the next day, and the following evening as they spread everywhere. It was a novel sight, defying the power of description. While in the past many conflagrations had taken place in the City-no one could cite how many and of what sort they had been - the fires ignited at this time proved all the others to be but sparks. The flames divided, took many different directions and then came together again, meandering like a river of fire. Porticoes collapsed, the elegant structures of the agorae toppled, and huge columns went up in smoke like so much brushwood. Nothing could stand before those flames. Even more extraordinary was the fact that burning embers detached themselves from this roaring and raging fire and consumed buildings at a great distance. Shooting out at intervals, the embers darted through the sky, leaving a region untouched by the blaze, and then destroying it when they turned back and fell upon it. The fire, advancing for the most part in a straight course driven by a north wind, was soon observed to turn aside as though fanned by a south wind, to move aslant, turning this way and that way as it unexpectedly charred and burned everything. Even the Great Church was endangered. Indeed, all the buildings lying in the direction of the Arch of the Milion and adjoining the gallery of Makron, and the structure also called The Synods came crashing to the ground, for neither the baked brick nor the deep set foundations could withstand the heat, and every- thing within was consumed like candlewicks.

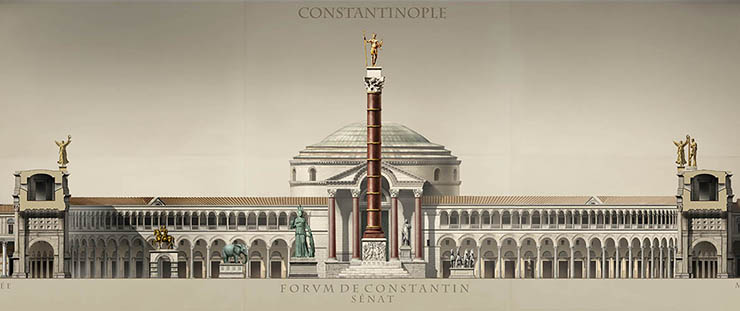

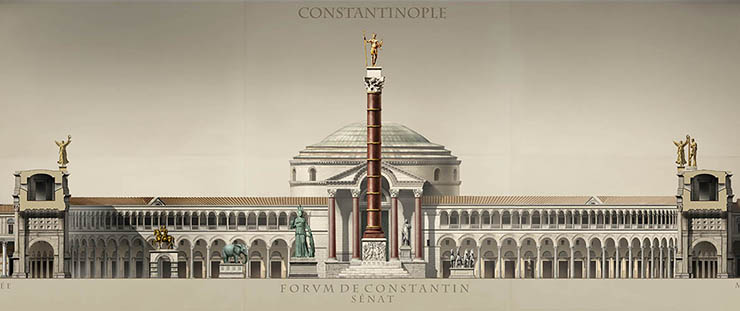

The first kindling of the fire, therefore, began at the synagogue of the Saracens (the latter is situated in the direction of the northern section of the City sloping toward the sea next to the church built in the name of Hagia Eirene, and, spreading breadthwise to the east, it abated at the Great Church; in the west it extended to the district called Perama, and thereafter it burst forth, enveloping the breadth of the City, and ex- pended its fury at the City's southern walls. The most extraordinary thing of all was that the fire, advancing gradually and leaping over the walls, so to speak, ravaged the dwellings beyond, and flying embers burned a ship sailing by. The so-called Porticoes of Domninos were also reduced to ashes, as well as the two covered streets originating at the Milion, one of which extended to the Philadelphion. The Forum of Constantine and everything between the northern and southern extremities were similarly destroyed. Not even the Hippodrome was spared, but the whole section towards the demes as well as everything leading down to [the harbor of] Sophia was engulfed in flames which extended to Bukanon and thence to all structures adjacent to the district of Eleutherios.

The first kindling of the fire, therefore, began at the synagogue of the Saracens (the latter is situated in the direction of the northern section of the City sloping toward the sea next to the church built in the name of Hagia Eirene, and, spreading breadthwise to the east, it abated at the Great Church; in the west it extended to the district called Perama, and thereafter it burst forth, enveloping the breadth of the City, and ex- pended its fury at the City's southern walls. The most extraordinary thing of all was that the fire, advancing gradually and leaping over the walls, so to speak, ravaged the dwellings beyond, and flying embers burned a ship sailing by. The so-called Porticoes of Domninos were also reduced to ashes, as well as the two covered streets originating at the Milion, one of which extended to the Philadelphion. The Forum of Constantine and everything between the northern and southern extremities were similarly destroyed. Not even the Hippodrome was spared, but the whole section towards the demes as well as everything leading down to [the harbor of] Sophia was engulfed in flames which extended to Bukanon and thence to all structures adjacent to the district of Eleutherios.

The flames, encompassing the City from sea to sea and dividing it as by a great chasm or a river of fire flowing through her midst, made it perilous for loved ones to join one another unless they crossed over in boats. The majority of the City's inhabitants were stripped then of their possessions as the flames reached out to those who were taken by sur- prise; those who had transferred their goods to other places of shelter also failed to salvage them. The fire, taking a winding course and moving in zigzag paths and branching off in many directions and returning to its starting point, destroyed the goods that had been moved. Woe is me! How great was the loss of those magnificent, most beautiful palaces filled with every kind of delight, abounding in riches, and envied by all.

The flames, encompassing the City from sea to sea and dividing it as by a great chasm or a river of fire flowing through her midst, made it perilous for loved ones to join one another unless they crossed over in boats. The majority of the City's inhabitants were stripped then of their possessions as the flames reached out to those who were taken by sur- prise; those who had transferred their goods to other places of shelter also failed to salvage them. The fire, taking a winding course and moving in zigzag paths and branching off in many directions and returning to its starting point, destroyed the goods that had been moved. Woe is me! How great was the loss of those magnificent, most beautiful palaces filled with every kind of delight, abounding in riches, and envied by all.

In the face of these most horrendous events, both Emperor Isaakios and his son Alexios were not in the least appalled. They prayed for the end of all things, these firebrands of the country, flaming in visage, thus personifying the incendiary angel of evil. Even before the conflagration had completely abated, a collection of sacred treasures again was made, more exhaustive than before, and melted down. The Latin host used the gold and silver provided them for their bodily needs as though they were profane metals and offered to sell them to whoever wished to buy. Considering themselves to be guiltless (for they were not ignorant whence came the monies awarded them), since they were only receiving what was owed them, they brought down the wrath of God on the Romans who prize their private possessions while defiling what belongs to God.

In the face of these most horrendous events, both Emperor Isaakios and his son Alexios were not in the least appalled. They prayed for the end of all things, these firebrands of the country, flaming in visage, thus personifying the incendiary angel of evil. Even before the conflagration had completely abated, a collection of sacred treasures again was made, more exhaustive than before, and melted down. The Latin host used the gold and silver provided them for their bodily needs as though they were profane metals and offered to sell them to whoever wished to buy. Considering themselves to be guiltless (for they were not ignorant whence came the monies awarded them), since they were only receiving what was owed them, they brought down the wrath of God on the Romans who prize their private possessions while defiling what belongs to God.

Since there was need for Alexios to receive assistance from the Latin forces as well (for his uncle, the former Emperor Alexios, having left Develton, occupied Adrianople, and delivered over the empire which he had repudiated to those who lusted insanely for power, neither desired nor dared to attempt to recover his throne), he induced Marquis Boniface to accompany him as his fellow general, but only after agreeing to pay sixteen hundredweight of gold. Marching out against [his uncle] Alexios [19 August 1203], he compelled him to flee more rapidly and much farther than before. He went the round of the Thracian cities, subjugating and then gleaning them (for his troops yearned to draw water often from the golden streams, and like those bitten by a venomous serpent whose poison causes intense thirst, they drank but could not be sated), and moving down as far as Kypsella, he returned to the palace [11 November 1203]; all the conspirators who had cooperated with his uncle Alexios in the blinding and removal of his father from the throne were hanged.

Isaakios impatiently awaited the opportunity to vent the rancor which had long smoldered in his breast against those who had treated him so abominably; and he did not cease speaking ill of his son, especially sincehe observed his own authority gradually slipping away from him and passing over to his son. He choked with rage at the transposition of....

names in the public acclamations; his son, taking precedence, was hailed with loud shouts which resounded through the palace while he followed, like an echo, the more spirited filial acclamations. Unable to influence events in any way, he mumbled under his breath; revealing the secrets of the innermost recesses of his heart, he defamed his son, contending that his usefulness was spent, that he was not at all trained in self-control, that his character had been formed by the worst habits, and that he kept company with depraved men whom he smote on the buttocks and was struck by them in return.

Not in vain or without cause did Isaakios inveigh against his son, for the latter committed many more outrageous offenses and sullied the majestic, all-glorious name of the Roman empire. With a few of his fol- lowers, he crossed over to the tents of the barbarians, where he engaged in drinking bouts and passed the day playing at dice. His playfellows, removing the gold-inlaid and bejeweled diadem from his head, put it on their own, and placed on Alexios a shaggy woolen headdress of Latin wool-spinning provenance.

Not only was Alexios deemed an abomination by sensible Romans for passing his time with the Latin nobles in such activities, but also his father, Isaakios, was no less despised as he busied himself with portentous delusions and unceasingly heeded the divinations and oracles more ineffable than those of his first reign. If he imagined himself to be sole ruler as before, he also shamelessly contended that he would unite the East with the West, girding himself with universal rule. He expected that at that time he would rub the blindness from his eyes, shed the disease of gout like the snake's slough, and be utterly transformed into a godlike man. Therefore, the most cursed of the monks (who let their beards grow full like a deep cornfield, these God-haters who, to their shame, don the habit dear to God and chase after royal banquets where they gulp down fresh and fat dishes) joined in establishing him by word as sole ruler as they dined with him and were served wine of a fine bouquet, unmixed with water. At times they embraced his gnarled hands, and, touching them to his eyes, they prophesied that these would be restored and strengthened as never before. He was, so to speak, utterly delighted by such sayings and leaped with joy at these ribald jests as though they were infallible prophecies.

The devotees of astrology were also admitted to his presence and he submitted to their counsels. He resorted to other measures, such as re- moving from its pedestal in the Hippodrome the Kalydonian boar, bristling up the, flowing hair on its back, and placing it in the Great Palace in the belief that he could thus forestall the onrush of the swinish and reckless populace of the city.

The wine-bibbing portion of the vulgar masses smashed the statue of Athena that stood on a pedestal in the Forum of Constantine, for it appeared to the foolish rabble that she was beckoning on the Western armies. She rose to a standing height of thirty feet and wore a garment made of bronze, as was the entire figure. The robe reached down to her feet and fell into folds in many places so that no part of the body which Nature has ordained to be clothed should be exposed. A military girdle tightly cinctured her waist. Covering her prominent breasts and shoulders ...was an upper garment of goatskin embellished with the Gorgon's head [the aegis]. Her long bare neck was an irresistible delight to behold. The bronze was so transformed by its convincing portrayal of the goddess in all her parts that her lips gave the appearance that, should one stop to listen, one would hear a gentle voice. The veins were represented dilated as though fluid were flowing through their twisted ways to wherever needed throughout the whole body, which, though lifeless, appeared to partake of the full bloom of life. And the eyes were filled with deep yearning. On her head was set a helmet with horsehair crest, and terribly did it nod from above.1483 Her braided hair tied in the back was a feast for the eyes, while the locks, falling loosely over the forehead, set off the braided tresses. Her left hand tucked up the folds of her dress while she pointed her right hand toward the south; her head was also gently turned southward, and her eyes also gazed in the same direction. Whence they who were wholly ignorant of the orientation of the points of the compass contended that the statue was looking toward the west and with her hand was beckoning the Western armies, thus erring in their judgment and misapprehending what they beheld.

As the result of such misconceptions, they shattered the statue of Athena, or, rather, guilty of ever-worsening conduct and taking up arms against themselves, they discarded the patroness of manliness and wisdom even though she was but a symbol of these. The emperors busied themselves in no more important task than the collection of monies as there was no satiating the recipients: the more they were given, the greater was their gold lust. There were citizens, indeed, who were in travail over the collection of taxes. As this was not proceeding equably (for the disgruntled populace, like a vast and boundless sea lashed by a wind, were seething with insurrection), they put an end to this scheme and milked by selection those who were reputed to be very rich, not as required to make butter, but in order to appease the ravenous hunger of the Latins. The heavy golden movables of the Great Church, together with the silver lamps, were removed and consigned to the flames, and simply thrown to the dogs for meat, and there was an unholy mingling of the profane with the sacred.

Nothing, however, was accomplished by these lawless measures. The exactors of money, who delighted in the simplemindedness of the Romans and mocked the stupidity of the emperors, wished to relieve them of some of their precious possessions and to compel others to carry these off, while others were to come forward to lead them to gold and some were to prepare to receive the spoils, and to do this without stopping. The chiefs of the hosts appeared in turn before the luxurious estates around the megalopolis, the holy temples along the Propontis, and the most splendid imperial edifices, where they took up arms one after the other, stripped them of everything within, and put these buildings to the torch. Not a single structure was spared by these barbarians who were borne by the Fates and hated the beautiful.

They sailed many times over to the shores of the City [December 1203 to January 1204] and gave battle. Victory smiled in turn upon the Romans and did not favor the enemy with invincibility on all sides.

Whence the City's populace, acquitting themselves like men, pressed the emperor to take part with the troops in the struggle against the adversaries, as they were patriots, unless indeed he was siding with the Romans with his lips only and had inclined his heart to the Latins. The promises made proved to be ineffectual; Alexios could not bring himself to take up arms against the Latins, thinking this to be unnatural and inexpedient, and his father, Isaakios, encouraged him to ignore the idle talk of the vulgar populace and to bestow the highest honors on those who had restored him to his country. Those who were left of the imperial family concurred in these views, a matter of companions pleasing their comrade Alexios. Some who associated with the Latins as comrades ignored the citizens' deliberations as old wives' gossip, being quicker to avoid battle with the Latins than an army of deer with a roaring lion.

Whence the City's populace, acquitting themselves like men, pressed the emperor to take part with the troops in the struggle against the adversaries, as they were patriots, unless indeed he was siding with the Romans with his lips only and had inclined his heart to the Latins. The promises made proved to be ineffectual; Alexios could not bring himself to take up arms against the Latins, thinking this to be unnatural and inexpedient, and his father, Isaakios, encouraged him to ignore the idle talk of the vulgar populace and to bestow the highest honors on those who had restored him to his country. Those who were left of the imperial family concurred in these views, a matter of companions pleasing their comrade Alexios. Some who associated with the Latins as comrades ignored the citizens' deliberations as old wives' gossip, being quicker to avoid battle with the Latins than an army of deer with a roaring lion.

Of all men, only Alexios Doukas (who, because his eyebrows were joined together and hung over his eyes, was called Mourtzouphlos as an adolescent by his companions), contriving to win the throne and the citizens' favor, dared to give battle against the Latins. Displaying his valor beyond a doubt, he engaged the enemy at the site called Trypetos Lithos and round about the arch leading thither [7 January 1204]. None of our own commanders who were present made any attempt whatsoever to come to his assistance because they were forbidden to do so by the emperor. Alexios Doukas's mount stumbled and slipped to its knees, and the entire enemy force would have fallen on the polemarch had not a band of youthful archers from the City who happened to be present stoutly defended him.

Of all men, only Alexios Doukas (who, because his eyebrows were joined together and hung over his eyes, was called Mourtzouphlos as an adolescent by his companions), contriving to win the throne and the citizens' favor, dared to give battle against the Latins. Displaying his valor beyond a doubt, he engaged the enemy at the site called Trypetos Lithos and round about the arch leading thither [7 January 1204]. None of our own commanders who were present made any attempt whatsoever to come to his assistance because they were forbidden to do so by the emperor. Alexios Doukas's mount stumbled and slipped to its knees, and the entire enemy force would have fallen on the polemarch had not a band of youthful archers from the City who happened to be present stoutly defended him.

The City populace, finding no fellow combatant and ally to draw the sword against the Latins, began to rise up in rebellion and, like a boiling kettle, to blow off steam of abuse against the emperors, and their long suppressed and hidden sentiment surfaced to the light of day. It was the twenty-fifth day of the month of January in the seventh indiction of the year 6712 [25 January 1204] when a great and tumultuous concourse of people gathered in the Great Church; the senate, the assembly of bishops, and the venerable clergy were compelled to convene thither and deliberate together as to who should succeed as emperor. We were entreated earnestly to speak spontaneously on this matter, to the effect that an attack be launched forthwith against the emperors and another elected to the throne. But we made no attempt to nominate a candidate before the assembly, for we realized full well that whoever was proposed for election would be led out the very next day like a sheep led to slaughter, and that the chiefs of the Latin hosts would wrap their arms around Alexios and defend him. The multitude, simpleminded and volatile, asserted that they no longer wished to be ruled by the Angelos family, and that the assembly would not disband unless an emperor to their liking were first chosen.

Knowing through bitter experience the obstinacy of men, we kept our silence, and in our unhappiness we let many tears flow down our cheeks, foreseeing what the future likely held in store for us. They anxiously groped for a successor to the throne, and on impulse proposed as emperor now this scion of the nobility and now that one. Tiring finally of the rabble-rousers and demagogues among them, they exhorted several members of our rank to put on the crown. Alas and alack! What could have Isaakios and Alexios Angelos been more heartrending and grievous than the trial of that time, or more absurd and mindless than the fatuity of those assembled? "Thou hast raiment; be thou our ruler," was all that was required. It was only on the third day that, seizing a certain youth whose name was Nicholas and surname Kannavos, they anointed him emperor against his will [27 January 1204].

When Emperor Alexios heard of these events (for Isaakios lay breathing his last, the extensive predictions of sole rule having proved false, dissolving like the dream of feverish sleep), he summoned Marquis Boniface to examine with him the present circumstances, and they both concluded that it was necessary to bring Latin forces into the palace to expel the new emperor and the populace who had elected him in assembly.

As soon as these deliberations were detected, Doukas seized the opportunity to begin the rebellion over which he had travailed. Taking along many of his kinsmen, he won over the eunuch in charge of the imperial treasuries, a worthless fellow who succumbed to the preferment of dignities and was unable to resist the temptation of unjust gain. Assembling the ax-bearers, he told them about the emperor's intention and convinced them to consider taking as the right action that which was desirable and pleasing to the Romans. In consequence, the emperor's overthrow was acted out in this wise.

Doukas visited the emperor in the dead of night [27-28 January 1204] (he was more easily recognized than anyone else, as he had been honored with the dignity of protovestiarios and wore on his feet buskins that differed in color from most). Swayed by passion, he announced to the emperor that his blood relations as well as a host of nameless men, but above all the barbarian contingent armed with axes, were standing at the doors after making furious assaults, eager to tear him to pieces with their hands because it was obvious that he was of one mind with the Latins and was dependent on their friendship. Terrified and taken aback by this news, he pleaded to be spared this fate. Doukas threw an ample robe over the emperor which covered his body down to his feet and escorted him out through a little-known postern into the pavilion within the palace complex, ostensibly to save him.

The emperor, shortly after these things had taken place in this wise, expressed profound gratitude and softly chanted the verse of David directly applicable to Doukas, "For in the day of mine afflictions he hid me in his tabernacle: he sheltered me in the secret of his tabernacle. He followed with other verses from the psalms of David: "His lips are deceitful in his heart, and evil has he spoken in his heart," and "To me they spoke peaceably but imagined deceits in their anger. With his legs secured by irons, he was cast into the most horrible of all prisons and thus "made darkness his secret placei as Doukas decked himself with the imperial insignia [28 January 1204].

Following these events, one faction assembled before Doukas and saluted him as emperor with the customary acclamations: another sided with Kannavos, who had remained in the temple; he was a man who was gentle by nature, of keen intelligence, and versed in generalship and war and its business. Inasmuch as the worst elements prevail among the Constantinopolitans (for truth is dearer to me than my compatriots), Doukas grew stronger and increased in power, while Kannavos's splendor grew dim like a waning moon. Not long afterwards, he was overpowered by Doukas's armed troops and thrown into prison, receiving no assistance from his subjects, all of whom had dispersed immediately following Doukas's proclamation [2 or 6 February 1204]

Twice Doukas offered Alexios the cup that quenches life; but when the lad proved more vigorous than the poison, secretly taking antidotes, Doukas cut the thread of his life by having him strangled, squeezing out his soul, so to speak, through the straight and narrow way, and sprang the trap leading to hell. He had reigned six months and eight days.

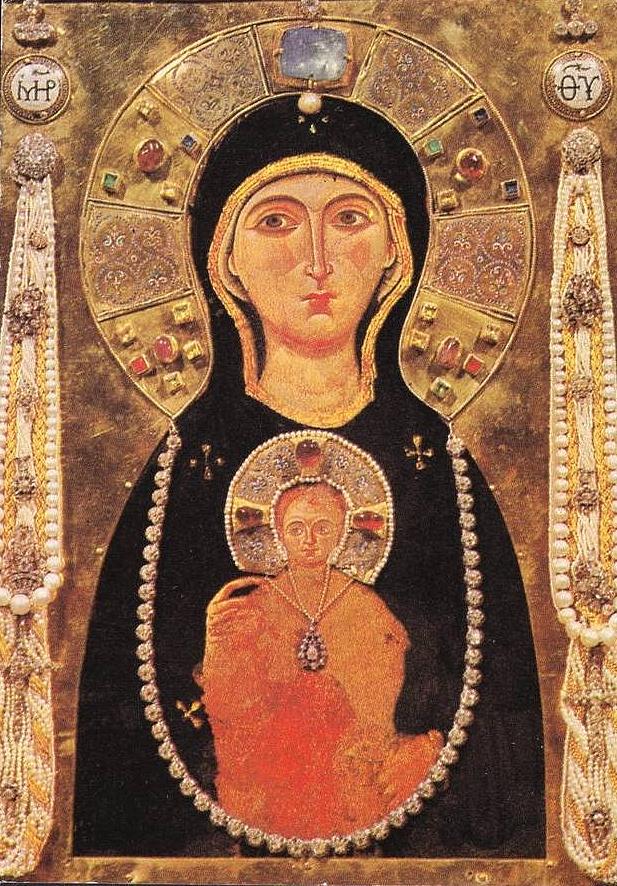

Above is the icon before its restoration showing the gems and pearls that were stolen in the robbery.

Above is the icon before its restoration showing the gems and pearls that were stolen in the robbery.

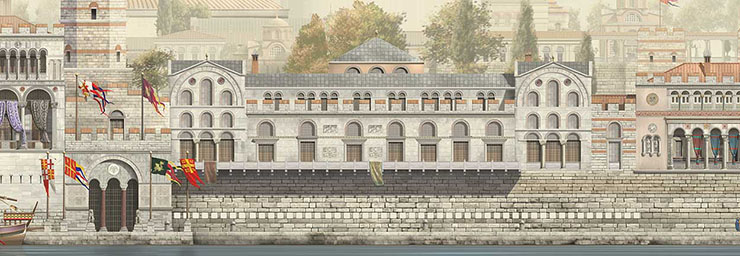

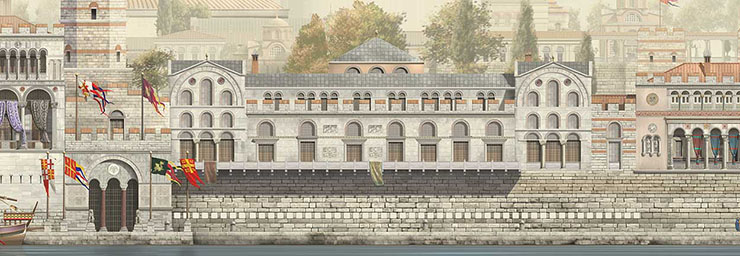

The Hodegetria icon in its shrine within the grounds of the Great Palace. you can see the 'angels'; on either side of the icon, attending to the curtain below:

The Hodegetria icon in its shrine within the grounds of the Great Palace. you can see the 'angels'; on either side of the icon, attending to the curtain below:

The first kindling of the fire, therefore, began at the synagogue of the Saracens (the latter is situated in the direction of the northern section of the City sloping toward the sea next to the church built in the name of Hagia Eirene, and, spreading breadthwise to the east, it abated at the Great Church; in the west it extended to the district called Perama, and thereafter it burst forth, enveloping the breadth of the City, and ex- pended its fury at the City's southern walls. The most extraordinary thing of all was that the fire, advancing gradually and leaping over the walls, so to speak, ravaged the dwellings beyond, and flying embers burned a ship sailing by. The so-called Porticoes of Domninos were also reduced to ashes, as well as the two covered streets originating at the Milion, one of which extended to the Philadelphion. The Forum of Constantine and everything between the northern and southern extremities were similarly destroyed. Not even the Hippodrome was spared, but the whole section towards the demes as well as everything leading down to [the harbor of] Sophia was engulfed in flames which extended to Bukanon and thence to all structures adjacent to the district of Eleutherios.

The first kindling of the fire, therefore, began at the synagogue of the Saracens (the latter is situated in the direction of the northern section of the City sloping toward the sea next to the church built in the name of Hagia Eirene, and, spreading breadthwise to the east, it abated at the Great Church; in the west it extended to the district called Perama, and thereafter it burst forth, enveloping the breadth of the City, and ex- pended its fury at the City's southern walls. The most extraordinary thing of all was that the fire, advancing gradually and leaping over the walls, so to speak, ravaged the dwellings beyond, and flying embers burned a ship sailing by. The so-called Porticoes of Domninos were also reduced to ashes, as well as the two covered streets originating at the Milion, one of which extended to the Philadelphion. The Forum of Constantine and everything between the northern and southern extremities were similarly destroyed. Not even the Hippodrome was spared, but the whole section towards the demes as well as everything leading down to [the harbor of] Sophia was engulfed in flames which extended to Bukanon and thence to all structures adjacent to the district of Eleutherios. The flames, encompassing the City from sea to sea and dividing it as by a great chasm or a river of fire flowing through her midst, made it perilous for loved ones to join one another unless they crossed over in boats. The majority of the City's inhabitants were stripped then of their possessions as the flames reached out to those who were taken by sur- prise; those who had transferred their goods to other places of shelter also failed to salvage them. The fire, taking a winding course and moving in zigzag paths and branching off in many directions and returning to its starting point, destroyed the goods that had been moved. Woe is me! How great was the loss of those magnificent, most beautiful palaces filled with every kind of delight, abounding in riches, and envied by all.

The flames, encompassing the City from sea to sea and dividing it as by a great chasm or a river of fire flowing through her midst, made it perilous for loved ones to join one another unless they crossed over in boats. The majority of the City's inhabitants were stripped then of their possessions as the flames reached out to those who were taken by sur- prise; those who had transferred their goods to other places of shelter also failed to salvage them. The fire, taking a winding course and moving in zigzag paths and branching off in many directions and returning to its starting point, destroyed the goods that had been moved. Woe is me! How great was the loss of those magnificent, most beautiful palaces filled with every kind of delight, abounding in riches, and envied by all. In the face of these most horrendous events, both Emperor Isaakios and his son Alexios were not in the least appalled. They prayed for the end of all things, these firebrands of the country, flaming in visage, thus personifying the incendiary angel of evil. Even before the conflagration had completely abated, a collection of sacred treasures again was made, more exhaustive than before, and melted down. The Latin host used the gold and silver provided them for their bodily needs as though they were profane metals and offered to sell them to whoever wished to buy. Considering themselves to be guiltless (for they were not ignorant whence came the monies awarded them), since they were only receiving what was owed them, they brought down the wrath of God on the Romans who prize their private possessions while defiling what belongs to God.

In the face of these most horrendous events, both Emperor Isaakios and his son Alexios were not in the least appalled. They prayed for the end of all things, these firebrands of the country, flaming in visage, thus personifying the incendiary angel of evil. Even before the conflagration had completely abated, a collection of sacred treasures again was made, more exhaustive than before, and melted down. The Latin host used the gold and silver provided them for their bodily needs as though they were profane metals and offered to sell them to whoever wished to buy. Considering themselves to be guiltless (for they were not ignorant whence came the monies awarded them), since they were only receiving what was owed them, they brought down the wrath of God on the Romans who prize their private possessions while defiling what belongs to God. Whence the City's populace, acquitting themselves like men, pressed the emperor to take part with the troops in the struggle against the adversaries, as they were patriots, unless indeed he was siding with the Romans with his lips only and had inclined his heart to the Latins. The promises made proved to be ineffectual; Alexios could not bring himself to take up arms against the Latins, thinking this to be unnatural and inexpedient, and his father, Isaakios, encouraged him to ignore the idle talk of the vulgar populace and to bestow the highest honors on those who had restored him to his country. Those who were left of the imperial family concurred in these views, a matter of companions pleasing their comrade Alexios. Some who associated with the Latins as comrades ignored the citizens' deliberations as old wives' gossip, being quicker to avoid battle with the Latins than an army of deer with a roaring lion.

Whence the City's populace, acquitting themselves like men, pressed the emperor to take part with the troops in the struggle against the adversaries, as they were patriots, unless indeed he was siding with the Romans with his lips only and had inclined his heart to the Latins. The promises made proved to be ineffectual; Alexios could not bring himself to take up arms against the Latins, thinking this to be unnatural and inexpedient, and his father, Isaakios, encouraged him to ignore the idle talk of the vulgar populace and to bestow the highest honors on those who had restored him to his country. Those who were left of the imperial family concurred in these views, a matter of companions pleasing their comrade Alexios. Some who associated with the Latins as comrades ignored the citizens' deliberations as old wives' gossip, being quicker to avoid battle with the Latins than an army of deer with a roaring lion. Of all men, only Alexios Doukas (who, because his eyebrows were joined together and hung over his eyes, was called Mourtzouphlos as an adolescent by his companions), contriving to win the throne and the citizens' favor, dared to give battle against the Latins. Displaying his valor beyond a doubt, he engaged the enemy at the site called Trypetos Lithos and round about the arch leading thither [7 January 1204]. None of our own commanders who were present made any attempt whatsoever to come to his assistance because they were forbidden to do so by the emperor. Alexios Doukas's mount stumbled and slipped to its knees, and the entire enemy force would have fallen on the polemarch had not a band of youthful archers from the City who happened to be present stoutly defended him.

Of all men, only Alexios Doukas (who, because his eyebrows were joined together and hung over his eyes, was called Mourtzouphlos as an adolescent by his companions), contriving to win the throne and the citizens' favor, dared to give battle against the Latins. Displaying his valor beyond a doubt, he engaged the enemy at the site called Trypetos Lithos and round about the arch leading thither [7 January 1204]. None of our own commanders who were present made any attempt whatsoever to come to his assistance because they were forbidden to do so by the emperor. Alexios Doukas's mount stumbled and slipped to its knees, and the entire enemy force would have fallen on the polemarch had not a band of youthful archers from the City who happened to be present stoutly defended him.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints