Would you like to see the beautiful illuminated family Gospels of John and Eirene? Click here to see it.

Originally these three figures were part of a collection of royal portraits, pictures of patriarchs, other church figures, icons of Christ and saints of the Orthodox church in the South Gallery. All of the walls and vaults were covered with gold mosaics. Everything is much larger than it appears in photographs, the angels in the vaults were three times life-size. The figures in the eastern part of the Southern Gallery had grown to several hundred over 500 years as successive reigns added to them. The gold backgrounds and the wide spaces between figures made it feel less crowded. The figures on the walls are high up so they could be seen above the crowds of people who assembled here for special ceremonies and meetings.

The mosaics are directly tied to illustrations done for John II in an illuminated gospels that were produced for his family by the Imperial scriptorium, probably located by the Nea Church on the grounds of the Great Palace. In John's gospels there are duplicates of these mosaic portraits in miniature. There is a very interesting - and tiny - portrait of Eirene. There are other manuscripts created in the same workshop, among them the famous Kokkinobaphos Homilies on the Life of Mary, the Codex Ebnerianus, a New Testament in the Bodleian Library and was also still in Constantinople in the 17th century. It was created for Manuel I's uncle, Isaac Komnenos, who was one of the founders of the Chora Church. His portrait appears in it. Another manuscript from the workshop is the Gospel Book of Theophanes in Melbourne, Australia.

The mosaics are directly tied to illustrations done for John II in an illuminated gospels that were produced for his family by the Imperial scriptorium, probably located by the Nea Church on the grounds of the Great Palace. In John's gospels there are duplicates of these mosaic portraits in miniature. There is a very interesting - and tiny - portrait of Eirene. There are other manuscripts created in the same workshop, among them the famous Kokkinobaphos Homilies on the Life of Mary, the Codex Ebnerianus, a New Testament in the Bodleian Library and was also still in Constantinople in the 17th century. It was created for Manuel I's uncle, Isaac Komnenos, who was one of the founders of the Chora Church. His portrait appears in it. Another manuscript from the workshop is the Gospel Book of Theophanes in Melbourne, Australia.

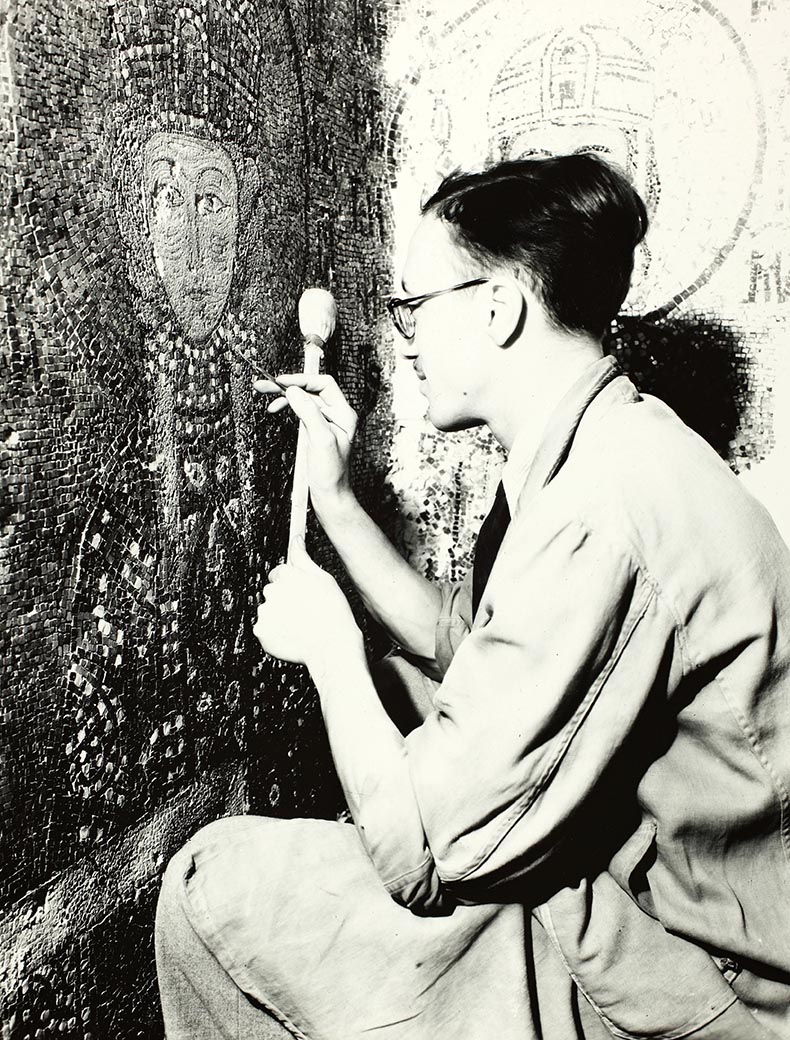

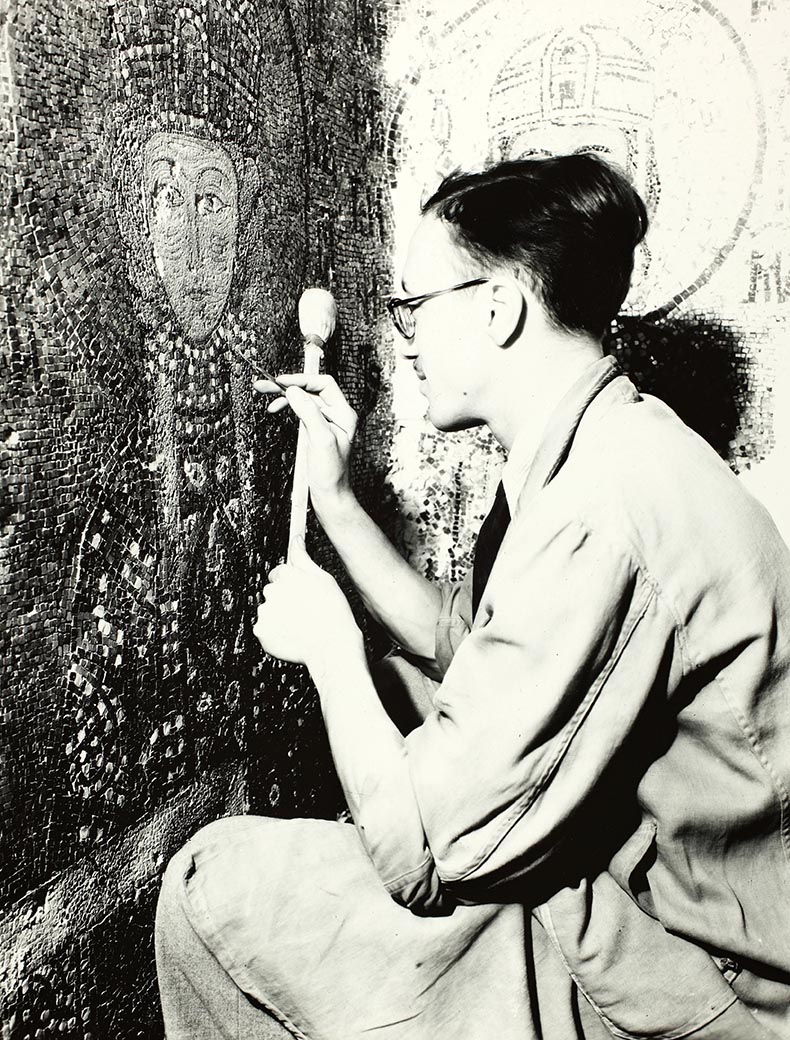

The guys who worked on this mosaic in 1934-35, included Richard "Dick" Gregory, who took extensive notes on the condition of he panel and what they did to conserve them. While they were working on the John panel they were also working on the Deesis. While they were removing plaster that had been applied to conceal the mosaics they discovered some parts of the mosaic were in precarious state and were about to fall off of the wall. Many copper clamps had to be inserted to reattach them.

There are three different types of gold mosaic used in the panel. The tesserae used in John's and Alexios's haloes are gold laid on green translucent glass, elsewhere in the panel the gold tesserae are laid on yellow and red translucent glass. This was an intentional choice which makes a subtle difference in the gold of the backgrounds and the halos. It was only done on John's halo. The gold background and the halos was laid on a red-painted background. John's and Alexios's haloes are outlined in blue while Eirene's is sea-green.

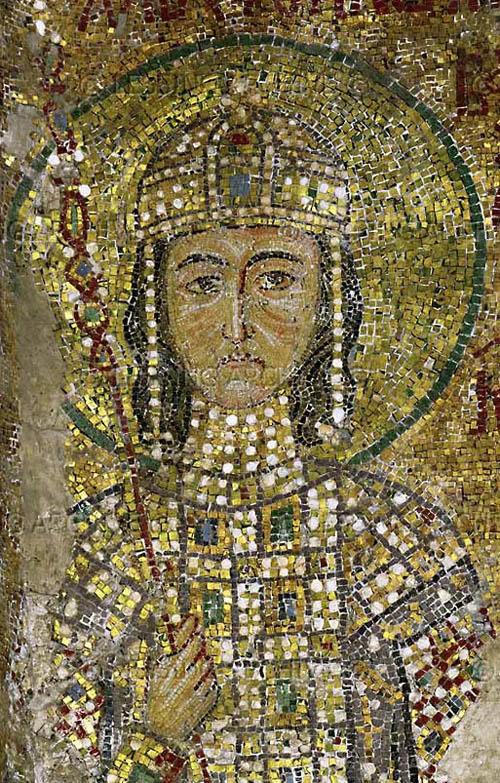

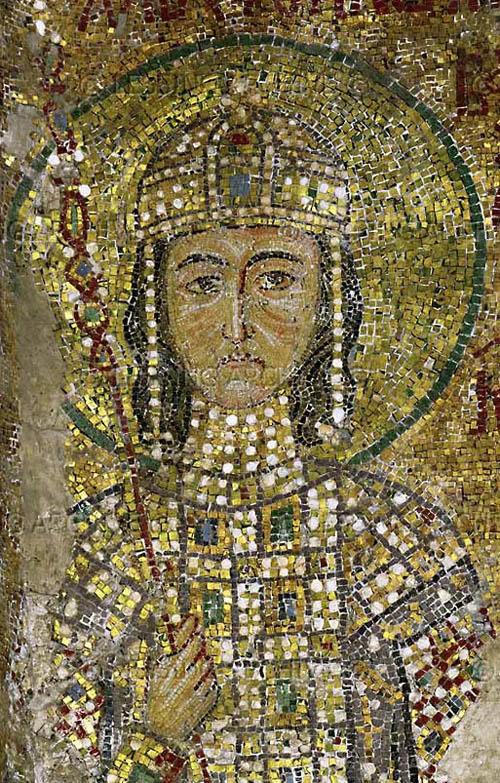

The face of John II was intentionally hacked at with a sharp spear and was in bad condition, the right eye was the best preserved. This vandalism reminds me of what happened to Christ on the cross, when His side was pierced by a lance. Today some of what looks like mosaic is actually brown wash underpainting. The face of Eirene was in better shape, which most of the damage done to the sides of her eyes. Eirene's face looks very pale because it is entirely made up of flat stone cubes without hardly any glass. The figure of their son Alexios was in really bad shape and required lots of attention to stabilize and save it. There was no intentional damage to the bodies of John and Eirene. Part of the right eye and the mouth of Christ were hacked out.

The entire panel was carefully painted in fresco colors to prepare it for the mosaicists. It is remarkable how detailed it was and extra attention was given to the inscription which was drawn in blue and then laid in sealing wax red. It was noted that the red letters of the inscription of Eirene's name were laid so they were raised slightly above the gold background. The letters were carefully laid with many tesserae, as many as 100 per letter.

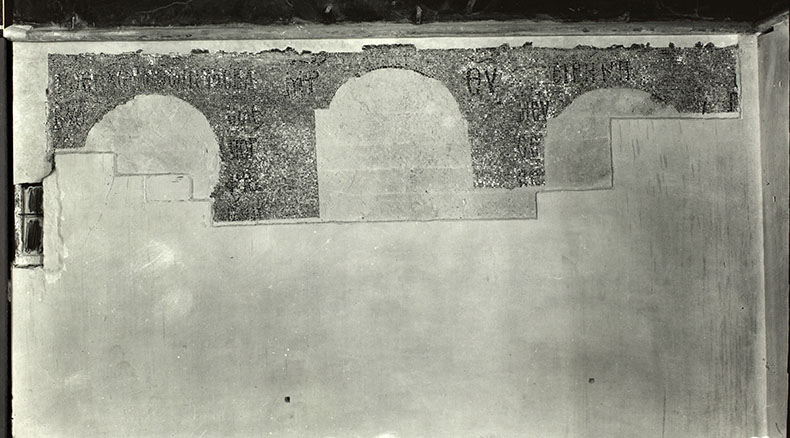

90% of these mosaics in the South Gallery been destroyed since 1850. Only ten figures in the South Gallery survive. During the restoration the wooden scaffold used in apse was dismantled and brought up to examine the vaults for mosaics. Some small traces were found of figures and the feet of Seraphim angels but no further action was taken to uncover them.

The image on the left is John II Komnenos after I restored his face. The original face was badly damaged after 1453. Look below to see it in its current state.

The image on the left is John II Komnenos after I restored his face. The original face was badly damaged after 1453. Look below to see it in its current state.

The John and Eirene panel has four full-length standing figures. In the center is the Mother of God holding her Divine Child, on her right is the Emperor John II Komnenos (1118-43), and on her left the Empress Eirene, daughter of Ladislas I of Hungary, and their son, Alexios. Her original name was Piroska. The name in Hungarian has it's root in the word red, which related to her complexion - not her hair color, which is a different word in Hungarian. She was an orphan, the ward of her cousin, King Coleman the Learned, and was raised in a Greek-speaking convent in her native Hungary. She must have come to Byzantium speaking the language of her new husband. She also would have known something of the ceremonies of the Greek church, having seen them performed in her convent-school. During her youth she saw a large number of new churches and cathedrals going up in her native land - all decorated with sculpture and paintings in the latest styles, inspired by Byzantine culture. Piroska would have seen the famous golden crown of Hungary that had been a gift of the Byzantine emperor and knew of it's history.

She was sent to Constantinople in 1104 to marry John when she was 16. That is when her name was changed from Piroksa to Eirene, as was the custom in the Byzantine court. 16 was a rather late age for a princess to marry a Byzantine prince. As a teenager who had been on her own most of her life she must have had a well-developed personality and some independence. She is described as "the Most Pious Augusta" in her inscription, which was a title given uniquely to her. We know that she was very, very religious and her father had been the same. He became a saint in the Catholic church.

Piroska-Eirene became pregnant immediately after their marriage and had twins, a boy Alexios and a daughter, Maria, 9 months later. Eventually she bore John eight kids - all of whom lived into adulthood. In 1118, when she ascended the throne, she had just borne her last child, Manuel, and was only 31. Two of her children had already married and she was a grandmother. Her family affairs were growing and taking up a lot of her time and energy.

Her mask-like portrait shows that she was both a foreigner and a great beauty of her time. She was a northerner, a blond type that the Byzantines were familiar with because of the the Varangian Guard were Viking and English. Her eyes are gray, outlined in blue. Her hair is made of two shades of light brown mosaic outlined in red. They would have also seen blond female warrior knights in the Crusader armies who came through Byzantium on their way east to the Holy Land. Her red dress also tells us she was not a 'born-in-purple' Byzantine princess, but a foreign one. After 8 children she still has a great figure.

In contrast to the Zoe Panel, attention seems here to have been divided almost equally among the the three central figures. Although the Virgin stands higher than them on a (now-missing) footstool, the Emperor and his wife assume the greater importance. Their heads are larger than the head of the Virgin and only by the slightest gesture in making their offering is a unity established between them and the Mother of God that tends to bring the three figures into a single composition. Although it may not be obvious there is also a hierarchical relationship between the Emperor and Empress. John is taller than his wife and has a slightly larger halo.

This panels differs from that of Zoe and Constantine on the left. The figures of John and Eirene are much higher on the wall. I think this was due to an altar set up below them. We know the South Gallery was used as an imperial chapel; the emperor would follow the service - especially the reading of the Gospels in this chapel. Perhaps it was here. The panel depicts an actual event in the chapel, the payment of salaries to the staff of Hagia Sophia. One can envision the other blank wall panels in this corner of the South Gallery once had their own illustrations of other emperors performing this act.

The panel was put up by the patriarch to commemorate the gift of money given by John to the church at his coronation that took place here. John's first-born son Alexios was made co-emperor with him. Alexios had three other brothers and four sisters, There was probably trouble among the brothers over the succession. The third boy, Issac, was lots of trouble throughout his life and was intentionally passed over by John when he died in favor of his youngest son, Manuel. Alexis died before his father and his brother Andronikos died escorting his brother's body back to Constantinople. Alexis and Andronikos were then accompanied by Issac to the Pantokrator Monastery for burial. Alexios, Andronikos and Manuel were all military men - generals in the army - who fought alongside their father in battle. Issac was more interested in literature, art and culture, it seems he had a different, more peaceful, nature than his brothers. John knew Issac as emperor would be a disaster for the empire, which needed a fighting emperor to defend it from the many foes that surrounded it.

Eirene died in an epidemic which struck the army in Bithynia in 1134. Her husband caught the same disease and had to return to Constantinople to recover from it. Her body was taken to the Pantokrator and interred in a great verde antico tomb.

John was described by his sister Anna, who detested her younger brother, as an ugly baby "The child had a swarthy complexion, broad forehead, lean cheeks a nose neither snub nor aquiline but something between the two, and very black eyes" although when he grew up he was known as "Handsome John". William of Tyre, a French crusader who knew John in later life greatly admired him as a soldier. He saw John in heroic hand-to-hand battles. He writes John was of medium height, had black hair and a black beard and had a swarthy complexion. William also knew Manuel, John's successor, very well and liked him very much. He says that Manuel was a noble ruler who was like a Frenchman in every way. Manuel spoke French which would have made easy for him to communicate with crusader knights like William. He was taller that his dad and had the same dark hair and complexion. Both of them lived most of their lives on military campaigns and would have had ruddy, sun-burnt faces.

John disliked court ceremony and was away from Constantinople most of the time which greatly curtailed it during his reign. Like his father, Alexis, he preferred to stay in the Blachernae Palace, which was 3 miles from Hagia Sophia in the northwest corner of the city. He and his wife attended daily religious services in a private chapel when they stayed there. They would come to Hagia Sophia for special events and the high feast days that were celebrated there, around 10 or 12 times a year including Easter. They could either stay in the Great Palace on those days or come by procession or on horseback from Blachernae. Their new foundation of the Pantokrator Monastery with its hospital was half way between there and Hagia Sophia.

The Emperor only wore the loros, a heavily gold-embroidered, gaudy kind of scarf that encased and immobilized the wearer in sewn-on gold ornaments, pearls and jewels, on a few very special occasions. It was heavy and cumbersome. You could not sit down or move around much when you were wearing it. It was claimed that one Imperial outfit like this had 30,000 pearls. The loros conveyed the earthly power and authority of the throne as made manifest in the wearer. The loros, it is said, recalls the winding sheet and symbolizes the death and resurrection of Christ. The word loros derives from the Latin word for leather; it was also called the diadema. The loros was worn draped over the divetesion, a long silk tunic.

The Empress Eirene is also dressed in a loros and a female tunic called a delmatikon in red silk.

In late Byzantine times the loros became thinner and had fewer gems.

In Hagia Sophia it was worn at Easter and Pentecost. There were three special guilds involved in the making of the loros, one that made Imperial clothes, another one that did gold embroidery and a third that made the attached jewels and enameled ornaments. Byzantium produced three kinds of gold embroidery; one that was made of sold gold wire, a second that was made of silk wrapped in gold and a third that was silk wrapped in flat silver bands that had been gilded. Gold embroidery was done on silk, wool and fine linen. Their work on linen was especially prized as Imperial gifts. These luxury workshops were located near the Chalke Gate of the Great Palace.

The crown would have been worn with many different costumes as well as military uniforms. The big stone in front was changeable and came in four colors associated with the circus factions of the Hippodrome, red, white, blue and green. The gem was laid on a backing of silk in a matching color. Wearing a crown on horseback was particularly hazardous and there are recorded incidents of Imperial crowns being thrown off and breaking on the pavement.

John believed his personal patroness was the Theotokos and he attributed all of his military successes to her active intervention (he called her his co-general), and thus wrapped all of his wars in the cloak of religion. He saw himself as the primary military defender of Christianity and Western civilization, a heavy spiritual responsibility and tremendous physical and psychological burden on him. Fighting the enemies of the empire was his number one job, by far. He spent most of his time outside of Constantinople fighting and was away for years at a time. John had mixed success in making the empire more secure and expanding the reconquest of territory that had been lost to crusader barons and the Turks. In the end he was killed by agents of the Latins of Antioch who poisoned him in order to end his interference and military pressure on their lands in the east. The Latins believed that his son Manuel was pro-Latin and "one of them".

John spent a great deal of time and treasure on the reconquest of the Komnenian homelands around Kastamon in Asia Minor. After capturing it following a siege of the fortress, John held a public triumph in Constantinople to celebrate it and thank the Theotokos for her role in it. Unfortunately, the Turks soon recaptured Kastamon. John had to return to Constantinople to recover from illness and was not with his troops in Asia Minor when Kastamon was attacked. John was deeply embarrassed by the loss of Kastamon and was compelled to negotiate with the Sultan for its return. Unfortunately, after gaining the fortress through treaty, it was lost once more to the Turks and John was forced to abandon it forever and evacuate the Christian population.

John had a serious plan to make the Byzantine lands of Asia Minor secure through the creation of a series of interconnected fortresses and cities along the border and deep right up to the sea. These strategic points were connected by roads to enable the army to move rapidly to deal with Turkish raids. He built new cities and fortresses that functioned as refuges for the civilian population and their farm or pastoral animals. He also built large city with a new palace for his family, courtiers and government officials that traveled with him.

John usually took his family with him on campaign and some of his children were born virtually on the battlefield. His family 'occupation' was military and he did not bother to give his boys a formal education. They learned about diplomacy and combat from their dad and his generals in the field. It was a great shame that he lost his oldest two boys before they could succeed him, since they were the best prepared for the job. The third, Isaac, was a mess and his father cut him out of the succession. The last born boy, Manuel, was made heir on John's deathbed.

Out of the hundreds that were made there are just a few surviving portraits of John. His portrait in Hagia Sophia shows him around 37 years of age tells us he was solidly built and sunburned from his years living outdoors.

Below is a marble relief possibly of John II. Perhaps it was set into the facade of the Pantokrator Monastery. The sculptor has carved the Imperial robes incorrectly; a chlamys was not worn over a loros. It is not clear what this means. Also, the emperor holds an orb surmounted with a Patriarchal cross, which is odd. Is this marble a Venetian creation imitating a Byzantine original? There is a second, almost identical relief in Venice, where this relief was found. These two reliefs have a possible third example in the Istanbul Archeological Museum.

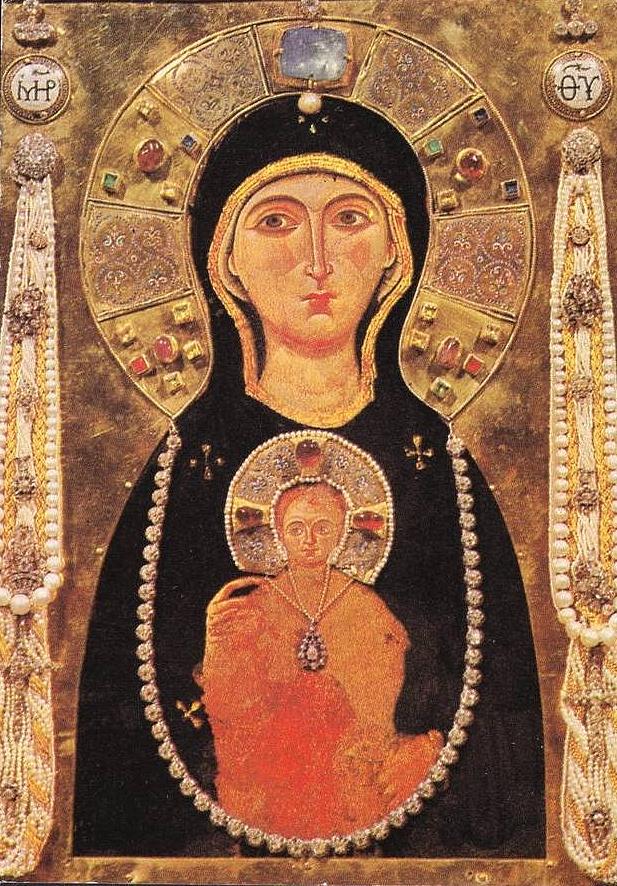

The Theotokos had been seen as the protectress of the Empire since the sixth century, but John took this relationship to a new, personal level. The icon was with him at all times, wherever he went. In this mosaic you can see the Theotokos side-by-side with the Imperial couple. An icon of the this image of the Theotokos was paraded around his military camps to inspire the troops, which was an innovation of his reign. Stories were circulated among the troops that the Theotokos spoke directly to John. He showed is devotion and humility by walking in front of his Imperial chariot carrying this icon in procession through the streets of Constantinople in thanks for a military victory in 1133. Although it may not be apparent to us now, the image of the Theotokos would have appeared hyper-realistic, vivid and even 'alive' to a Byzantine viewer. Her face is modeled with many lines of pink glass which give a vibrant rosy color to her cheeks and chin. The artist has also used bright red to drawn the lines of the eye-lids and the side of the right nostril. The eyes of the Theotokos and Christ both look directly at the viewer with a disturbing intensity. Thankfully, the sides of the Virgin's mouth are softened, which makes the face feel more human.

The Theotokos had been seen as the protectress of the Empire since the sixth century, but John took this relationship to a new, personal level. The icon was with him at all times, wherever he went. In this mosaic you can see the Theotokos side-by-side with the Imperial couple. An icon of the this image of the Theotokos was paraded around his military camps to inspire the troops, which was an innovation of his reign. Stories were circulated among the troops that the Theotokos spoke directly to John. He showed is devotion and humility by walking in front of his Imperial chariot carrying this icon in procession through the streets of Constantinople in thanks for a military victory in 1133. Although it may not be apparent to us now, the image of the Theotokos would have appeared hyper-realistic, vivid and even 'alive' to a Byzantine viewer. Her face is modeled with many lines of pink glass which give a vibrant rosy color to her cheeks and chin. The artist has also used bright red to drawn the lines of the eye-lids and the side of the right nostril. The eyes of the Theotokos and Christ both look directly at the viewer with a disturbing intensity. Thankfully, the sides of the Virgin's mouth are softened, which makes the face feel more human.

Below is an image of the Imperial Door to the South Gallery. Now this door opens out into space. The wooden staircase was attached to this door. Tomas Thomov has provided me with this image. It shows the lcation of graphi of a blessing hand. This area was covered with graffiti. The mosaic of John II and Eirene is to the left. She how the floor is messed up. This indicates the amount of traffic that went through the door.

On either side of the Theotokos the Emperor presents a bag of money and the empress offers a donation to the church and clergy of Hagia Sophia. This ceremony took place in the South Gallery and the mosaic records the actual event, which would have been attended by hundreds of people who worked in the Great Church. It has been calculated that the upper galleries of Hagia Sophia could hold around 2,500 people. The South Gallery would hold around 600 people. In order to save money John and his father had recently reduced the paid clergy of Hagia Sophia from 700 to 500, which is still a huge number. All of them could be assembled at one time in the South Gallery. This does not include the thousands of staff that ran and maintained the day-today operations of the church. Once a year the clergy was paid their full salary in a money bag like the Emperor holds. Each bag had the amount they carried in gold written on the outside and was tied with a red silk ribbon that carried the Imperial seal in red wax. Sometimes they received special bonuses or grants during the year outside their annual wages. The emperor was seated at sturdy long table during the presentation of annual salaries with the bags of gold and coin. All of the senior clergy and staff were handed their bags directly from the hands of the emperor. Annual salaries usually included gifts in kind like food and clothes.

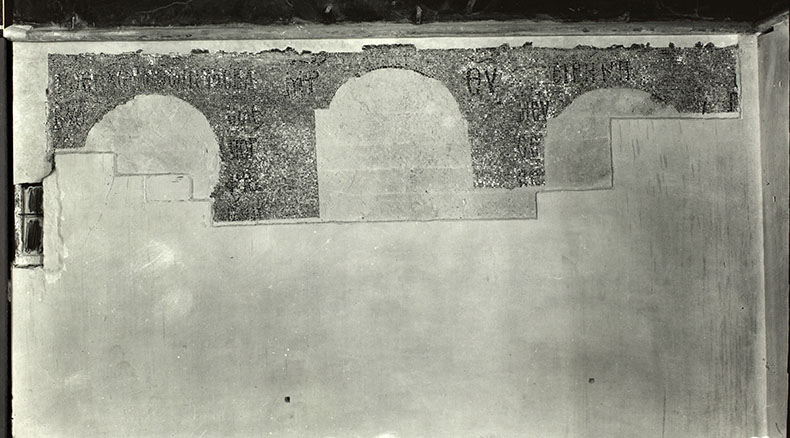

Below you can see an exterior view from the 19th century of the eastern wall of the South Gallery. You can see the famous door that used to open onto a great wooden spiral staircase that opened onto an elevated passageway to the Great Palace via the Chalke Gate. John and Eirene would have used this path to privately enter Hagia Sophia; and would have used it to move up and down between the south gallery and the nave of Hagia Sophia though the Chapel of the Holy Well. The door now opens out into space, because the staircase and passage disappeared long ago. On the inside, on both sides of the door, you can still find graffiti, including one left by a servant named Philip of the Metropolitan of Kiev, Cyprian, probably in 1387 (he made three trips to Constantinople, so it could have been any one of them) which reads "Lord help thy slave Philip, Mikita's son, panter of Cyprian, metropolitan of Kiev and all Russia" in Cyrillic. There are lots of graffito here, including many inscriptions and drawings of thing like birds and ships.

There was some sort of shrine in front of this mosaic. This would have been a place where candles could have been placed. You can see in this diagram of the floor and the marks in the floor. It looks to me like there was a parapet with columns, too.

At Hagia Sophia the clergy was highly trained in the study and interpretation of scripture and preaching. Everything was done in an everyday, educated Greek that everyone could understand. The clergy was the primary way the people learned about world events and Imperial proclamations through homilies and sermons. The reduction in the number of paid clergy pushed this highly-educated and sophisticated clergy from Great Church out to the provinces, which raised the level of culture there. There was a lack of clergy outside of Constantinople, most priests had multiple churches they served there, so extra priests and deacons were welcome. Education in the provinces was centered on churches and these clerics would have had an immediate positive impact on their schools. In the late 12th century several of these provincial academies grew in size and reputation to the point that they started to function as self-governing institutions with their own staff and traditions. These teachers, whether they were in the capital or places like Thessalonika, were focused on two things; one, teaching their students to speak, read and write good Greek and two, instructing them in Orthodox Christian theology. Village students often learned the gospels by memorization before they learned to read.

While he was on campaign John would send regular newsletters to the clergy of Hagia Sophia for them to 're-broadcast' to the city the latest news and events from the front. These scrolled newsletters were copied over hundreds of times and sent all over the empire from where ever the Emperor was residing at the time. A Byzantine Emperor could easily send out 500 letters a day when he was traveling. Imagine the number of secretaries and scribes that were required. One can expect at least some of them would have been illustrated. These newsletters were a long standing practice. Hundreds of years of them were stored in the Great Palace and were used by historians. The Imperial bureaucrats saved everything. In Byzantium three copies of every contract were required. One copy was for each of the signers and the third was sent to the Imperial archive. When these letters and documents perished they left behind hundreds of thousands of lead seals that were attached to them.

In the middle of this panel the Theotokos offers her precious Son to the world. Thus the Emperor and Empress witness and participate in this act of divine love and share in her grace. Ceremony was very important to court life and everyone in Constantinople was a participant on one level or another. At the very top was the Imperial family who had a special sacred role and spiritual responsibility to play. Whenever they visited Hagia Sophia they became part of ceremonies that had been refined over hundreds of years. This primarily involved the celebration of the Divine Liturgy and prayer services. It is hard for us to imagine a world in which people completely believed that God and saints personally intervened in human history by defending cities and protecting emperors. The Byzantines believed Christ and his mother had really appeared on the walls of the City and intervened to save Constantinople several times in the past. However, they hoped and prayed for deliverance in 1204 and 1453 without success. Tens of thousands of them were raped and massacred in Hagia Sophia on May 29th, some in front of this very mosaic. Why did God abandon them?

The panels extend down to almost the level of the windowsill. The marble frame around the Zoe panel is not original and might have been added in the 19th century. It looks like the plain marble cornice above the John panel has been reset, too.

When complete, the height of the mosaic was 2.47 m - 8.5 feet. The width of the panel, from the window which bounds it on the right to the pilaster, is 2.76m - so it's a square panel. Originally it filled the space between two marble fillets which framed it above and below; now a strip of gold background 5 to 5.5cm. in width, just under the upper fillet, as well as all the lower part of the mosaic, to the height of 1m, 3.3 feet, from the lower fillet, no longer remain. On the left of the panel, a vertical band of gold background, 13 cm. wide, which extended to the embrasure of the window, has also disappeared. The surface of the gold background of this panel is somewhat smoother than that of the Zoe Panel. In consequence light is not quite so luminously scattered, but the interstices between the cubes are assertive and prevent the face of the panel from becoming anything like burnished gold or a blank metallic plane.

Technical Descriptions

Mother of God

The figure of the Theotokos is slightly higher in the picture than the figure of the emperor and of the Empress. It may be supposed that she stood on a low footstool. She holds in front of Her the Christ Child represented in a seated position.

Her nimbus is gold with outline of sealing-wax-red, and on either side of her head, in large letters made of black violet glass tessellae are the usual monograms Mother of God.

Her nimbus is gold with outline of sealing-wax-red, and on either side of her head, in large letters made of black violet glass tessellae are the usual monograms Mother of God.

Her countenance is treated as for an icon. The features are sharply drawn was with wide heavy brows, long straight nose, thin, firm-set lips, and blue eyes looking forward in soft serenity. Marble cubes of deep rose-red suffused with shining white are set closely, interstices scarcely visible, with a conscious assurance that every change from cube to cube will add to the general incorporeal radiance.

In contrast to the representation of flesh and blood attained in the portraits of the Imperial Family, this is a devout religious image, which fondly expresses its creator's understanding of the relation of the Virgin to mankind.

In contrast to the representation of flesh and blood attained in the portraits of the Imperial Family, this is a devout religious image, which fondly expresses its creator's understanding of the relation of the Virgin to mankind.

The head and the upper part of the body of the Mother of God are wrapped in a maphorion of white-violet blue, giving the semblance of wool, with crosses woven in gold thread for the forehead and shoulders. Gold edging frames the face in an unbroken line and hangs almost vertically from the forearms. The end of the mantle, thrown over the left shoulder, is fringed with gold crosses. The cap, covered by the maphorion, is lightest in hue of the vestments, and the chiton, with tight-fitting sleeves, is of the same material and colour. The garments are not of the fathomless blue found in the figures of the vestibule where the structure and setting of the glass result in indescribable vibration. The impression is of applied colour rather than of colour attained by the breaking of surfaces.

Her hands are relatively small. Around the left thumb is twisted a handkerchief of the appearance of raw silk with a light tendril-green stripe on the sides and fringe.

The Holy Child

The Child Jesus has a round chubby face, with large prominent forehead and full chin. Grave black-violet eyes stare from dark hollows. Darkest auburn hair at the back of the head falls in short curls below the ears. Three tiny locks lie in the center of the brow. With a tender sense of color, cubes are set in close precision as in the face of the Virgin. Only the pale-pink tones of the stone here are softer, the range more restricted and the contrast less severe as in the actual fresher flesh of the child.

Christ is dressed in a chiton and himation of tissue of gold, its highlights breaking into crests of silver-green. He wears an undershirt of dark teal-blue (the same color is in His halo) silk that has been lined in white. Christ gives the Orthodox blessing and holds a parchment scroll of the Gospels. His head is surrounded by a cruciform nimbus outlined in pale silver-green; silvery limbs of the cross, in gold ground, set off the head in strong relief against stretches of blue.

Here we do not find the simple, pervading, childlike character of the young Christ in the Vestibule panel, but a somewhat hypnotized being superposed on infancy in an effort, perhaps, to evoke a more dogmatic image of ageless divinity.

Upwards from the ragged line of the mosaics at the level of the knee the figure of the Mother of God is well preserved. Her face and hands are slightly scarred by the loss of cubes; more seriously damaged by time is the Child's face, but happily His features are better preserved than John's.

The Emperor

The Emperor holding the bag of gold is vested in full ceremonial robes encrusted in jewels; he is drawn like all these figures with firmest contours, his head imperceptibly turned towards the Mother of God. The face is much damaged by time; many cubes had fallen but the fresco painting of the setting-bed, from which we painstakingly removed the plaster, together with the remaining mosaics completely preserve his features. A study of this head in its shattered state of fresco and mosaic again reveals, as in the figure of Zoe, the technical procedure of the artist. In his fresco painting the artist was able to clarify and integrate his perception, and to prepare for the subtle and baffling organization of his cubes. His individual perception and the symbolism of his subject merge in the final achievement.

John has a broad, full, swarthy face, prominent lower jaw, and s lightly protruding chin, a deeply care-lined forehead, brown eyes with dark arched eyebrows, a firm mouth and tightly closed lips. His long, thin, wavy moustache is carefully brushed to the sides of a parting and his semicircular well-kept beard is still thick on the lower side of the chin but is growing grey and is thinning towards the cheeks and below the mouth. The moustache and beard are a lighter tone than the hair. Long dark locks frame the face and hang to the level of the chin. His complexion is slightly florid although the artist depicts a certain heaviness in an aging face. John stands here august, serious, and in deep gravity - a soldier and a statesman, looking every inch the man in whom his father Alexios placed unalterable confidence as his successor.

John has a broad, full, swarthy face, prominent lower jaw, and s lightly protruding chin, a deeply care-lined forehead, brown eyes with dark arched eyebrows, a firm mouth and tightly closed lips. His long, thin, wavy moustache is carefully brushed to the sides of a parting and his semicircular well-kept beard is still thick on the lower side of the chin but is growing grey and is thinning towards the cheeks and below the mouth. The moustache and beard are a lighter tone than the hair. Long dark locks frame the face and hang to the level of the chin. His complexion is slightly florid although the artist depicts a certain heaviness in an aging face. John stands here august, serious, and in deep gravity - a soldier and a statesman, looking every inch the man in whom his father Alexios placed unalterable confidence as his successor.

The emperor wears the kamilaukion, a conical helmet-shaped crown of gold, divided with reddish violet lines of enamel and studded with pearls. Two frontal jewels are surmounted by an equal-limbed cross of pear-shaped stones fixed with their pointed end to the round pearl which forms the center. The vertical limbs of the cross have the light of rubies, the horizontal, the gold blue of lapis-lazuli.

The divitission of the usual imperial reddish-violet silk with floral designs woven in gold is close fitting: the sleeves, adorned with armlets and cuffs, are loose at the shoulder and tight at the wrist; armlets are inlaid with pearls and jewels, the shoulder-piece slopes to the chest beneath the loros.

Much like those worn by Constantine IX, three-quarters of a century earlier, the shoulder-piece and loros are woven in gold thread and violet silk, bedecked with pearls and with carnelians, beryls and lapis-lazuli, mounted in squares and rectangles whose edges flash with sprays of pearls. The loros, attached to the collar, falls to the waist where it is covered by the part from behind, which is drawn close across the body and is caught up to hang over the wrist. The lining of the loros, woven a a white silk pattern on a cinnabar-red ground, showing a dentellated circle with a row of short oblique strokes, is visible below the hand.

The head of John is framed by an inscription in lambent red. It begins above the head, continues at his left, and finishes at the right. The inscription of John reads: John in Christ the God, faithful King born in the purple and Autocrat of Romans, the Komnenos.

The Empress

Eirene's real name was Piriska. She was born in 1086, the daughter of the Hungarian King Ladislaus I and Adelheid of Rheinfelden. She married John when she was 18 and had four daughters and four sons with him (including at least one set of twins) , the last being born in 1116. Their youngest son became the Emperor Manuel I. Eirene, who died on August 13, 1134, was canonized in the eastern church because of her extraordinary acts of charity for the poor. It should be noted that crowns could not be worn in church like this, that her hair is a wig (was she really a blond?) - and she is heavily made-up. Women of all classes wore makeup in Byzantium wore face power, rouge, eyeliner and eyeshadow. Eirene died in Bithynia where she was traveling with her husband on a military campaign to retake Kastamouni which had been captured by the emir of Melitene. Eirene traveled with her husband on most of his military campaigns which tells us she and her husband were close and enjoyed each other's company . The fact she bore him so many healthy children so close together also tells us she had a strong constitution and she and John were seldom apart.

Eirene's real name was Piriska. She was born in 1086, the daughter of the Hungarian King Ladislaus I and Adelheid of Rheinfelden. She married John when she was 18 and had four daughters and four sons with him (including at least one set of twins) , the last being born in 1116. Their youngest son became the Emperor Manuel I. Eirene, who died on August 13, 1134, was canonized in the eastern church because of her extraordinary acts of charity for the poor. It should be noted that crowns could not be worn in church like this, that her hair is a wig (was she really a blond?) - and she is heavily made-up. Women of all classes wore makeup in Byzantium wore face power, rouge, eyeliner and eyeshadow. Eirene died in Bithynia where she was traveling with her husband on a military campaign to retake Kastamouni which had been captured by the emir of Melitene. Eirene traveled with her husband on most of his military campaigns which tells us she and her husband were close and enjoyed each other's company . The fact she bore him so many healthy children so close together also tells us she had a strong constitution and she and John were seldom apart.

The stiff jewel-robed figure of the empress is represented holding in her long and slender hands a scroll of parchment known to record donations. Her foreign birth is betrayed by her broad face, wide forehead, and long cold grey eyes. She is pictured in strong contrast to the dark coloring of the emperor. Pallor representing the white powder and pale rouge in her make-up renders her face almost devoid of shadows: mask-like, without a blemish. In the fashion of the time, her eyebrows are shaved or plucked and are drawn here with cubes imitating the color of walnut juice and honey. Black eyebrows with blond hair were much admired in Irene's time, and the royal coiffeur for this occasion, in acknowledged conformity to taste, elaborated a head-dress for the empress, perhaps by adding to her own hair long, heavy blond tresses. Her sidelong glance is directed hesitatingly towards the central figure, her lips are pursed, her expression constrained.

Above is the tomb of Eirene in Verde Antica Serpentinite Breccia, which was formerly in the Pantokrator Monastery. Until at least the late 19th century it was seen outside the former church, where it had been moved and was used as a fountain. In 1960 it was moved to Hagia Sophia where you can see it in the outer narthex. It was carved with simple crosses in circles, which have almost vanished with time. Recently, the foremost authority on the Pantokrator, Robert Ousterhout, has pointed out that this tomb is too large to have been moved in through any of the doors of the church. He feels that this tomb came from one of the mausoleums of the nearby Church of the Holy Apostles. When the church was demolished by Mehmet II this tomb was saved. There are 14 marble tombs preserved in Hagia Sophia today, most of them are in the garden.

The raiment of the empress is like that of other imperial personages, whose representations in Byzantine art make possible the reconstruction and description of the here partly vanished mosaics. Over a tunic of which only the high jeweled collar is seen, Irene wears the long imperial divitission of heavy flaming red silk into which is woven with gold thread a profusion of curves, spirals, and flowering scrolls. Their designs are found in earlier Fatimid and pre-Fatimid weavings and stucco, and later in the rich figured silks of the Bursa (Brusa) and Usküdar (Scutari). In the hundred years denoted by the art of these panels, the taste of the the imperial weavers shows no predilection for motives of birds or animals. Wherever in the Near East the origin of the bifurcation of the ivy leaf is sought, the ambit union of these particular forms here creates a new synthesis and reveals a secondary nature from a fresh intuition in the artists of Constantinople in the time of the genius of the Komnenoi.

The long wide opening of the right sleeve is bordered by a running design in blue and gold thickly set with pearls, and the same ornament is repeated on the arm-bands. Partly hidden by the loros, the shoulder-piece is woven in blue floriated design on gold ground, bordered with a double row of pearls, interspersed with gems and trimmed on its edge with sprays of pearls. Around the neck the opening has a string of pearls between rows of small garnets or carnelians. Like the shoulder-piece the loros is of heavy cloth of gold woven with floriated scroll pattern in deep sapphire blue terminating in jewels and is similarly bordered: it ends over the forearm in a lengthwise fold, leaving only half of the scroll pattern visible.

The girdle is woven in deep sea-green with an oval buckle composed of a carbuncle set in pearls. Below the girdle the shield shaped lower part of the loros is ornamented with a heart-like design in deep blue enhanced by jeweled flowers on a gold ground. The center is a beryl.

The empress wears a gold modiolos greatly surpassing all the other crowns in magnitude. It has the usual semblance of battlemented walls and gates, shining translucently with the lustre of jewels: beryls, carnelians, carbuncles, lapis-lazuli, and with rows of pearls tier upon tier, until sparkling particles on invisible wires appear actually to fly upwards around the cross that surmounts the crown.

Beneath the crown a diaphanous red flame-like veil, thrown back over the head is visible about the hair on both sides and in its pearl trimmed edges above the shoulders.

The earrings are pear shaped carnelians or carbuncles in gold setting with three pearl pendants much like the Roman crotalia.

Silver green rims the nimbus of Eirene.

The head of Eirene, like that of John, is framed by an inscription in the same red. It begins above the head, continues at her right, and finishes at the left. The inscription of Eirene reads: Eirene the most pious Augusta.

Alexios

Alexios was born in 1006 and had a twin sister, Maria. He was born while on campaign with his father and mother in the Balkans. He and his three brothers grew up with the army, seeing most of the empire first-hand and even entered some foreign lands. His father had made him co-emperor in 1122 when he was 16. This mosaic was most likely created around the time of his coronation. Alexios married Dobrodjeja Mstislavna, Princess of Kiev, who was renamed Eirene. The name Eirene was commonly given by the Byzantines to foreign princesses who married into the Imperial House. It was an arranged marriage and Alexios had no real choice in the selection of his first wife. Like Holbein and Henry VIII portraits were made of prospective wives and delivered to Constantinople for review by Alexios and his parents. There were professional portrait artists who worked for the Imperial court. Hundreds of portraits in paint, mosaic and marble depicting the Imperial family for both domestic and international audiences. All of the royal courts of Europe and the Mid-East were sent copies.

We don't know what happened to Dobrodjeja Mstislavna, she must have died because Alexios married a second time to a Georgian princess named Kata, whom he may have met before they married since he traveled all over Asia Minor with his father and could have been presented to her. Alexis had one daughter, named Maria Komnene, who after a wild and troubled life died insane in 1167. Alexios died of a brain fever at the age of 36 while on a military campaign against the Turks in Asia Minor with his father in 1142 and was buried in the Pantokrator Monastery near his mother. Tragically, his brother Andronikos died at sea bringing the body of his brother back to Constantinople. His father, John, followed them into death a year later and was laid to rest alongside his wife and sons.

The transition from the gold surface of the main wall, on which the John panel is set, to the side of the pilaster with the portrait of Alexios, is effected by a slight rounding of the corner. The mosaic is preserved on Alexios' right side to a point a little below his waist and, on the left, to a little below his shoulders.

The treatment of the figure of Alexios is freer and more forceful than that of the other figures, as if done at one sitting, straight from the artist's soul in realization of vision. There is a great feeling for the power of fundamental colours which set at varying angles to the light produce and endless variety of tones. The modeling of the face is in greens and reds and yellowish greys with dashes of whitish cubes that recall the manner of Van Gogh. The hair is darkest lustrous brown, the large sad eyes are hazel with dark lashes and thick eyebrows, the nose thin and straight with delicate wings, the mouth small and sensitive with grieved drooping corners. A slight swelling is noticeable in the upper part of the face: the boy looks nephritic. It is a troubled, transient face. And this impression is intensified by the nimbus and the robes, where gold leaf is laid over translucent pale green glass enveloping the figure in changeable greenish lights deepening the gloom. This portrait even more than the others painted in ultra-photographic Roman-portrait vision seems yet to recognize the ordinance in Semitic religions against representation.

The treatment of the figure of Alexios is freer and more forceful than that of the other figures, as if done at one sitting, straight from the artist's soul in realization of vision. There is a great feeling for the power of fundamental colours which set at varying angles to the light produce and endless variety of tones. The modeling of the face is in greens and reds and yellowish greys with dashes of whitish cubes that recall the manner of Van Gogh. The hair is darkest lustrous brown, the large sad eyes are hazel with dark lashes and thick eyebrows, the nose thin and straight with delicate wings, the mouth small and sensitive with grieved drooping corners. A slight swelling is noticeable in the upper part of the face: the boy looks nephritic. It is a troubled, transient face. And this impression is intensified by the nimbus and the robes, where gold leaf is laid over translucent pale green glass enveloping the figure in changeable greenish lights deepening the gloom. This portrait even more than the others painted in ultra-photographic Roman-portrait vision seems yet to recognize the ordinance in Semitic religions against representation.

The crown worn by Alexios is like the one worn by the emperor his father, only the top is a little less pointed and its ornamentation is in different gems. The upper stone in front has the glow of the ruby, the lower, the pallor light sapphire. In both crowns the cross is of pearls, with a gold centre, and the prependulia are alike, save in the form of the crosses at the ends. This crown - and the crown of his father - really depict the ones they wore. In the Gospel of John II, which was produced for the use of his family, there are miniatures of John and Alexios wearing these crowns.

The crown worn by Alexios is like the one worn by the emperor his father, only the top is a little less pointed and its ornamentation is in different gems. The upper stone in front has the glow of the ruby, the lower, the pallor light sapphire. In both crowns the cross is of pearls, with a gold centre, and the prependulia are alike, save in the form of the crosses at the ends. This crown - and the crown of his father - really depict the ones they wore. In the Gospel of John II, which was produced for the use of his family, there are miniatures of John and Alexios wearing these crowns.

Alexios is vested in a divitission of the same material and pattern-weaving as that worn by the Autocrator. Of this we see but a part of the right shoulder and the outline of the right sleeve, and the entire left shoulder and a narrow strip along the loros. The ornament adorning the sleeve is a plaque of heavy gold tissue crossed by red squares on which pearls are applied and in the centre of which are stones of the hues of amethyst and beryl. From the open end of the right sleeve projects the tight gold wristlet of the chiton adorned with a stone of beryl and two pearls. Pearls encrust the high collar of the chiton.

The shoulder-piece and the loros are also similar to those worn by his father. Throughout the execution of these vestments is more rapid and free than in the figure of the emperor.

Alexios' hand is small and slender with a narrow wrist. He holds a scepter, pressed close to his chest. The jewel-topped staff of the gold scepter casts its red shadow; a succession of carbuncles, emeralds, and amethysts, separated at inverts by pearls is tipped with a pearl cross.

Near the lower margin of the existing mosaic there is a fragment of design difficult to identify: it consists of a red triangle with three pear shaped pearls mounted in a gold, disposed fan-like from a round central pearl. Beneath the base of the triangle is a line of tessellae of fine red brick, the use of which here is unique to these panels. This fragment we venture to think represents the end of a case containing the scroll held by Alexios in his left hand.

The red inscription runs around Alexios, like the one which frames the head of his father, runs first above his head, then to his left, and continues down the right on the John panel at Irene's side. It reads: Alexios in Christ, faithful King of the Romans, the born in the purple.

Chronology of John Panel

No trace of juncture is visible in the mosaic background or is to be detected in the setting bed between the figures of Alexios and the other personages of the panel. Yet marked differences in the mosaic painting may be noted. The figure of Alexios is not set on the same level as the other figures, the gold tessellae filling his nimbus, as was said, are of a greenish hue, whereas the other nimbi are of yellow gold. The green outline of the nimbus of Alexios is also of a different hue from the green outline of the nimbus of Irene. The jewels on his vestments are not in claw-setting, and in this respect differ from the setting of the jewels on John's garments, and finally, as again it has been noted, there is remarkable difference in the handling of the Alexios and of the other imperial figures. Thus it seems probably that the John and Alexios mosaics are the work of different years but, we think, of the same unknown hand; the figures on the wall we conjecture, in the autumn of 1118, to commemorate John's accession, and the figure on the pilaster was added in 1122 when Alexios, in his seventeenth year, was proclaimed co-emperor. Indeed, Alexios here looks like a youth of this age. I don't agree with Whittemore's opinion that the mosaic was made in two stages because the setting bed is continuous.

Lettering, Position of Panels, Iconography

The dates of the inscriptions are set, within narrow limits, by the events. The writing on the Zoe Panel is formal and architectural; the lines balance the figures and heighten their faces. Freer and less easily disengaged from the figures are the John and Alexios titles. They seem to have been conceived as emanations from the personages they surround.

The Position of the Panels

The place assigned to the imperial panels - far from the entrance, in the Eastern part of the South Gallery is exceptional. But the placing of the figures of emperors and founders in or near the Sanctuary is not without analogy in a number of churches. Their position is perhaps not without a liturgical significance in that the persons represented were commemorated in the prayers of the Holy Services and they themselves often took their place beside their dramatic counterparts.

This explanation holds good for the position of the mosaics in Hagia Sophia.

Originally the Galleries of the Great Church were designed for the assemblage of women. Later the South Gallery served a more specific and official purpose. From the ninth century on councils were certainly held here. The mosaic representation of the Church, in the hands of the figure of Justinian in the Vestibule reveals the fact that the Patriarchal Palace and consequently the metatorion, or private liturgical imperial apartment on the second floor, which it contained, were connected with this part of the Church. Here, in the South Gallery, is also a marble-paved ramp, obviously for imperial use, leading from the South-West Vestibule and further, built into the thickness of the buttress, is a small and exquisitely domed chapel for the use of two or three imperial personages. The Book of Ceremonies vividly describes the emperor praying in this Gallery with lighted candle in hand and passing through it when returning to the Palace.

Thus these imperial portraits form an appropriate decoration for a part of the Church which was the scene of private imperial ceremony.

Iconography

The iconographical significance of both the Zoe and John Panels is identical. Each represents an "imperial offering", in composition similar to that of the panel of the South-West Vestibule which has been discussed in a preceding Report. Only instead of the model of the City and of the Church, presented by the Founder of the City and the Builder of the Church, here the figures hold the purse and the scroll. Into the John Panel was brought the figure of young Alexios in a revival of an ancient custom for an emperor to portray himself with his heir apparent.

The symbolism of such a picture is revealed by an epigram of Theodore Prodomos, referring to a painting in which John II Comnenos is represented. In the verses the emperor worships Christ, the God, and brings to Him 'A tribute of gold and silver', such as his subjects render to himself. The offering is made in thanksgiving and in the hope of new favors to come. These successive offerings spoken of by the poet give us a Byzantine conception of the Christian World in which individual life was of small moment compared with the unified effort of society.

A panegyrist of the twelfth century, Eustatios of Thessaloniki, paraphrasing a verse from the Psalms, tell us that the greatness of the emperors is evident from the fact that God is in the midst of them as their guide and prototype. Imperial portraits like these in Hagia Sophia, in which Christ or the Mother of God is the central figure, present pictorially this idea.

The image of Christ on the Zoe panel is characteristic of the art at the end of the eleventh century and throughout the twelfth. A similar treatment of details is fond in many monuments of this period - the closed book, the throne without back, the rounded footstool. The figure is sharply drawn, the scrutiny of the oblique gaze is accented by the uplifted eyebrow. Although some of these traits already appear in the ninth century in a miniature of Cosmas Indicopleustes in the Vatican, this image of Christ is in definite contrast to the more solemn type with the calm, benignant gaze 'of the large eyes that see all things from above', fostered, until this moment, in Christian art. Representations closely related to that of the Zoe Panel begin to appear only from the end of the eleventh century, and during the twelfth century, at Torcello; in St. Mark's on the soffit of an arch leading from the southern apse to the sanctuary; at Mount Athos; in the Deesis of the tympanum at Vatopedi, and more generally in Sicily in the dome of the Martorana and at Monreale in the scene of the coronation of King William.

A survival of this type looms unexpectedly much later on the Russian icons of the Novgorod School. There, however, Christ is never represented full length; the treatment of the beard is essentially Russian, but the piercing gaze directed aslant and the raised eyebrows are preserved. Moreover, the icon bears the significant title - 'the Saviour of the angry eye."

Yet this is but a reminiscence. Christ of the Zoe Panel, while representing a typical variant of the iconography of the eleventh to twelfth centuries, is chronologically at the beginning of the series. Most surviving examples, as we have seen, are distributed on the periphery of the empire, but the creation of this image must be in this way attributed to Constantinople.

Now the figure of the Virgin with the Child in the John panel is of a much earlier type. Various representations - designated sometime by the title Kyriotissa - spring probably from a venerated icon on the Church of Theotokoy ta Kyroi, founded during the reign of Theodosius II by the Prefect of Constantinople Kyros Constantine. The earliest example known to us emerges from the sixth century on a lead seal of Mauricios Tiberios. In the twelfth century the type appears on the coinage of Manuel I Comenneos, and the image of the Kyriotissa is found in paintings from the eight century on to post Byzantine times.

It is possible that the popularity of this icon was due largely to a fervent imperial devotion. On a seal of the seventh century four emperors - probably Constantios II with his sons - are represented, as on the John Panel, around a Virgin of the Kyriostissa type. It has lately been suggested that, until the time of the Isaurian Dynasty, this icon was considered a palladium of the Byzantine emperors. If this be true, the discovery of the mosaic in Hagia Sophia tends to prove that it was held as an object of the same veneration as late as the time of the Komneni.

In the faces of the Virgin and Child new elements are discernible which the artists of the twelfth century imparted to the interpretation of an ancient theme. The aquiline nose and heavy eyebrows of the Virgin are characteristic of Oriental types introduced into the art of this period. The drawing of the Child lacks the freshness and spontaneity of the tenth century Christ in the South-West Vestibule. He is here characterized by a round head, fleshy nose, heavy jaw. A Christ Child of this type appears in the next reign on the coins of Manuel I Komnenos and in contemporary paintings, and further under the name of Emmanuel, this image obtained a wide popularity which it has held to the present day in religious art of the Orthodox Eastern Church.

The Panghia and the Child of the John Paul and the Christ in the Zoe Panel are characterized by an iconic rigidity resulting from a sustained repetition of forms.

The figures of John and Irene, and to a lesser degree the imperial portraits of the Zoe Panel reflect this same conventionalism.

Far different is the face of Alexios. Although a contemporary composition it is painted in an intensity of vision which entrains the stimulus of the identification of spirit and establishes a conduit by which a tide of sentiment is caused to flow to us.

Such in part is an account of the rediscovery of these mosaics and a record of the first reflections produced by a study of them.

In the enclosure of Hagia Sophia is revealed a gallery of imperial portraits and religious paintings uniting palaces with the Great Church.

The Zoe Panel is one of the last works of the Macedonian Dynasty, the panel of John and Alexios is among the earlier works of the Komnenoi. On the same wall is represented the art of the end of one epoch and that of the beginning of the next.

Our knowledge of both Byzantine art and history is enriched by these paintings, for they are the abstract and brief chronicles of the time.

The technical descriptions at the bottom of the page are from The Mosaics of Hagia Sophia at Istanbul, Third Preliminary Report Work Done in 1935-1938 by Thomas Whittemore and published in 1942

Bob Atchison

Above is the icon before its restoration showing the gems and pearls that were stolen in the robbery.

Above is the icon before its restoration showing the gems and pearls that were stolen in the robbery.

The Hodegetria icon in its shrine within the grounds of the Great Palace. you can see the 'angels'; on either side of the icon, attending to the curtain below:

The Hodegetria icon in its shrine within the grounds of the Great Palace. you can see the 'angels'; on either side of the icon, attending to the curtain below:

The mosaics are directly tied to illustrations done for John II in an

The mosaics are directly tied to illustrations done for John II in an

The Theotokos had been seen as the protectress of the Empire since the sixth century, but John took this relationship to a new, personal level. The icon was with him at all times, wherever he went. In this mosaic you can see the Theotokos side-by-side with the Imperial couple. An icon of the this image of the Theotokos was paraded around his military camps to inspire the troops, which was an innovation of his reign. Stories were circulated among the troops that the Theotokos spoke directly to John. He showed is devotion and humility by walking in front of his Imperial chariot carrying this icon in procession through the streets of Constantinople in thanks for a military victory in 1133. Although it may not be apparent to us now, the image of the Theotokos would have appeared hyper-realistic, vivid and even 'alive' to a Byzantine viewer. Her face is modeled with many lines of pink glass which give a vibrant rosy color to her cheeks and chin. The artist has also used bright red to drawn the lines of the eye-lids and the side of the right nostril. The eyes of the Theotokos and Christ both look directly at the viewer with a disturbing intensity. Thankfully, the sides of the Virgin's mouth are softened, which makes the face feel more human.

The Theotokos had been seen as the protectress of the Empire since the sixth century, but John took this relationship to a new, personal level. The icon was with him at all times, wherever he went. In this mosaic you can see the Theotokos side-by-side with the Imperial couple. An icon of the this image of the Theotokos was paraded around his military camps to inspire the troops, which was an innovation of his reign. Stories were circulated among the troops that the Theotokos spoke directly to John. He showed is devotion and humility by walking in front of his Imperial chariot carrying this icon in procession through the streets of Constantinople in thanks for a military victory in 1133. Although it may not be apparent to us now, the image of the Theotokos would have appeared hyper-realistic, vivid and even 'alive' to a Byzantine viewer. Her face is modeled with many lines of pink glass which give a vibrant rosy color to her cheeks and chin. The artist has also used bright red to drawn the lines of the eye-lids and the side of the right nostril. The eyes of the Theotokos and Christ both look directly at the viewer with a disturbing intensity. Thankfully, the sides of the Virgin's mouth are softened, which makes the face feel more human.

Her nimbus is gold with outline of sealing-wax-red, and on either side of her head, in large letters made of black violet glass tessellae are the usual monograms Mother of God.

Her nimbus is gold with outline of sealing-wax-red, and on either side of her head, in large letters made of black violet glass tessellae are the usual monograms Mother of God.

John has a broad, full, swarthy face, prominent lower jaw, and s lightly protruding chin, a deeply care-lined forehead, brown eyes with dark arched eyebrows, a firm mouth and tightly closed lips. His long, thin, wavy moustache is carefully brushed to the sides of a parting and his semicircular well-kept beard is still thick on the lower side of the chin but is growing grey and is thinning towards the cheeks and below the mouth. The moustache and beard are a lighter tone than the hair. Long dark locks frame the face and hang to the level of the chin. His complexion is slightly florid although the artist depicts a certain heaviness in an aging face. John stands here august, serious, and in deep gravity - a soldier and a statesman, looking every inch the man in whom his father Alexios placed unalterable confidence as his successor.

John has a broad, full, swarthy face, prominent lower jaw, and s lightly protruding chin, a deeply care-lined forehead, brown eyes with dark arched eyebrows, a firm mouth and tightly closed lips. His long, thin, wavy moustache is carefully brushed to the sides of a parting and his semicircular well-kept beard is still thick on the lower side of the chin but is growing grey and is thinning towards the cheeks and below the mouth. The moustache and beard are a lighter tone than the hair. Long dark locks frame the face and hang to the level of the chin. His complexion is slightly florid although the artist depicts a certain heaviness in an aging face. John stands here august, serious, and in deep gravity - a soldier and a statesman, looking every inch the man in whom his father Alexios placed unalterable confidence as his successor. Eirene's real name was Piriska. She was born in 1086, the daughter of the Hungarian King Ladislaus I and Adelheid of Rheinfelden. She married John when she was 18 and had four daughters and four sons with him (including at least one set of twins) , the last being born in 1116. Their youngest son became the Emperor Manuel I. Eirene, who died on August 13, 1134, was canonized in the eastern church because of her extraordinary acts of charity for the poor. It should be noted that crowns could not be worn in church like this, that her hair is a wig (was she really a blond?) - and she is heavily made-up. Women of all classes wore makeup in Byzantium wore face power, rouge, eyeliner and eyeshadow. Eirene died in Bithynia where she was traveling with her husband on a military campaign

Eirene's real name was Piriska. She was born in 1086, the daughter of the Hungarian King Ladislaus I and Adelheid of Rheinfelden. She married John when she was 18 and had four daughters and four sons with him (including at least one set of twins) , the last being born in 1116. Their youngest son became the Emperor Manuel I. Eirene, who died on August 13, 1134, was canonized in the eastern church because of her extraordinary acts of charity for the poor. It should be noted that crowns could not be worn in church like this, that her hair is a wig (was she really a blond?) - and she is heavily made-up. Women of all classes wore makeup in Byzantium wore face power, rouge, eyeliner and eyeshadow. Eirene died in Bithynia where she was traveling with her husband on a military campaign

The treatment of the figure of Alexios is freer and more forceful than that of the other figures, as if done at one sitting, straight from the artist's soul in realization of vision. There is a great feeling for the power of fundamental colours which set at varying angles to the light produce and endless variety of tones. The modeling of the face is in greens and reds and yellowish greys with dashes of whitish cubes that recall the manner of Van Gogh. The hair is darkest lustrous brown, the large sad eyes are hazel with dark lashes and thick eyebrows, the nose thin and straight with delicate wings, the mouth small and sensitive with grieved drooping corners. A slight swelling is noticeable in the upper part of the face: the boy looks nephritic. It is a troubled, transient face. And this impression is intensified by the nimbus and the robes, where gold leaf is laid over translucent pale green glass enveloping the figure in changeable greenish lights deepening the gloom. This portrait even more than the others painted in ultra-photographic Roman-portrait vision seems yet to recognize the ordinance in Semitic religions against representation.

The treatment of the figure of Alexios is freer and more forceful than that of the other figures, as if done at one sitting, straight from the artist's soul in realization of vision. There is a great feeling for the power of fundamental colours which set at varying angles to the light produce and endless variety of tones. The modeling of the face is in greens and reds and yellowish greys with dashes of whitish cubes that recall the manner of Van Gogh. The hair is darkest lustrous brown, the large sad eyes are hazel with dark lashes and thick eyebrows, the nose thin and straight with delicate wings, the mouth small and sensitive with grieved drooping corners. A slight swelling is noticeable in the upper part of the face: the boy looks nephritic. It is a troubled, transient face. And this impression is intensified by the nimbus and the robes, where gold leaf is laid over translucent pale green glass enveloping the figure in changeable greenish lights deepening the gloom. This portrait even more than the others painted in ultra-photographic Roman-portrait vision seems yet to recognize the ordinance in Semitic religions against representation. The crown worn by Alexios is like the one worn by the emperor his father, only the top is a little less pointed and its ornamentation is in different gems. The upper stone in front has the glow of the ruby, the lower, the pallor light sapphire. In both crowns the cross is of pearls, with a gold centre, and the prependulia are alike, save in the form of the crosses at the ends. This crown - and the crown of his father - really depict the ones they wore. In the Gospel of John II, which was produced for the use of his family, there are miniatures of John and Alexios wearing these crowns.

The crown worn by Alexios is like the one worn by the emperor his father, only the top is a little less pointed and its ornamentation is in different gems. The upper stone in front has the glow of the ruby, the lower, the pallor light sapphire. In both crowns the cross is of pearls, with a gold centre, and the prependulia are alike, save in the form of the crosses at the ends. This crown - and the crown of his father - really depict the ones they wore. In the Gospel of John II, which was produced for the use of his family, there are miniatures of John and Alexios wearing these crowns.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints