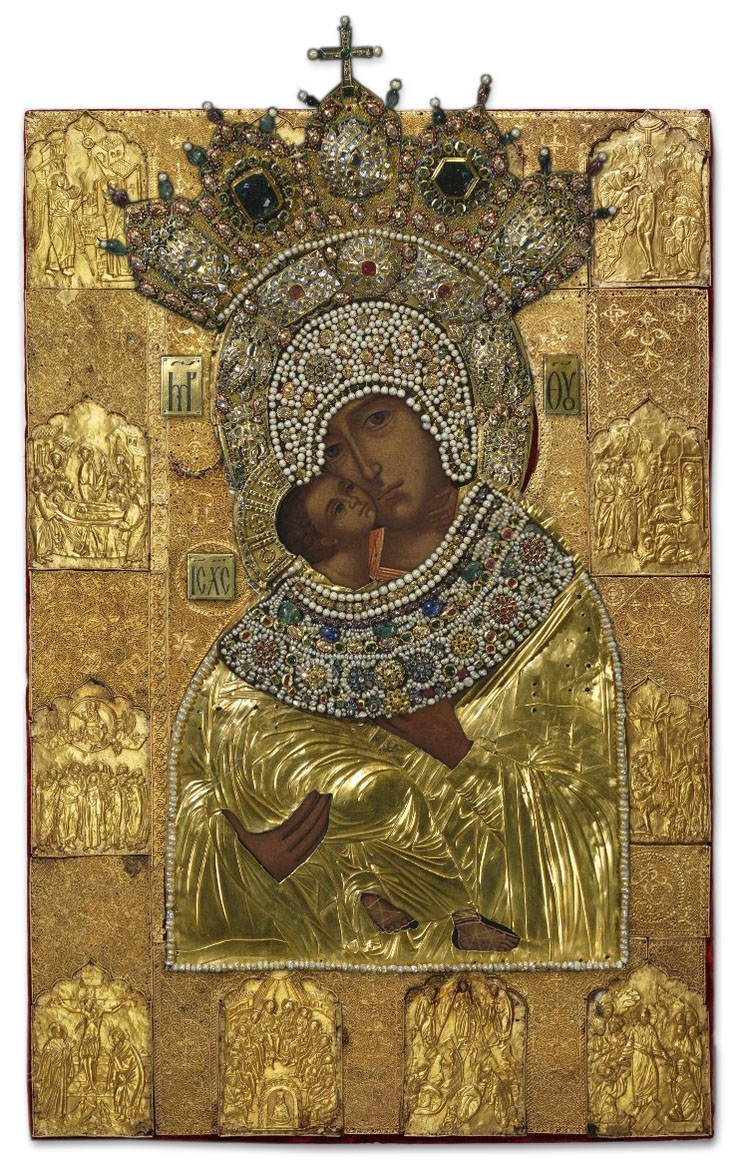

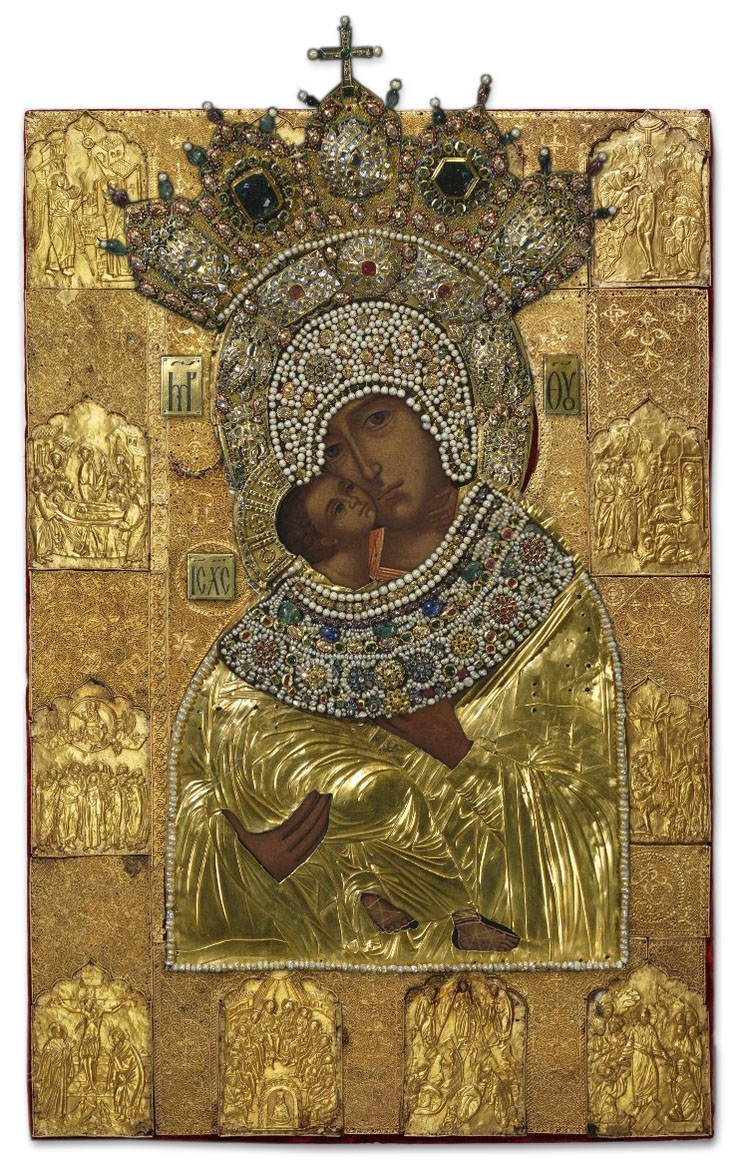

Above is the 15th century Byzantine gold cover (oklad) and 17th century gold clothing-halo of the Virgin of Vladmir. I have restored the painting, the covers are no longer on the icon, they are in the Kremlin Armory Museum. I have used Andrei Rublev's perfect, 15th century copy here. This oklad was brought in 1410 from Constantinople to Moscow by Metropolitan Photius, a Byzantine ecclesiastic newly appointed Metropolitan of all Russia by the patriarch of Constantinople.

Above is the 15th century Byzantine gold cover (oklad) and 17th century gold clothing-halo of the Virgin of Vladmir. I have restored the painting, the covers are no longer on the icon, they are in the Kremlin Armory Museum. I have used Andrei Rublev's perfect, 15th century copy here. This oklad was brought in 1410 from Constantinople to Moscow by Metropolitan Photius, a Byzantine ecclesiastic newly appointed Metropolitan of all Russia by the patriarch of Constantinople.

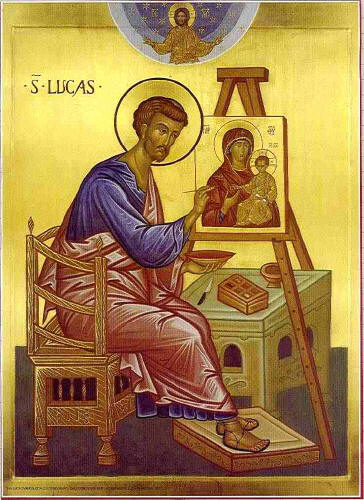

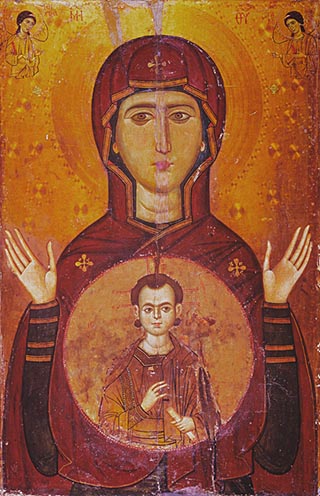

Left, St. Luke painting the Hodegetria icon.

Left, St. Luke painting the Hodegetria icon.

In Russia it is called Vladimirskaya Presvyatuiya Bogoroditsui — the “Vladimir Most Holy Mother of God" and the Russians believed it was painted by St. Luke.

Russian Chronicles report the icon arrived in Russia before 1131. It was brought to Kiev and placed in the convent of the Virgin in Vyshgorod. The icon is of the "Eleuosa" or "Tenderness" Mother of God holding the Christ child close to her body. It was painted during the reign of John II Comnenus and was probably either a gift from the Emperor or the Patriarch John IX Agapetos who held the throne from 1111 - 1134. It could not have been sent by Patriarch Luke Chrysoberges, as it is generally claimed, since he served from 1156 - 1169 and the icon was already in Russia by then. The icon may be associated with events surrounding the betrothal and marriage of John's first son, Alexios to the Russian princess Dobrodeia-Evpraksia, daughter of Grand Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich and Christine of Sweden of Kiev in 1122. A Byzantine delegation bearing gifts was set from Constantinople to prepare Dobrodeia for her voyage to Constantinople and to act as escorts for her trip. The delegation would have consisted of aristocratic members of the Byzantine court and members of the Comnenian family. They would have brought Dobrodeia's wedding clothes so she could arrive in Constantinople fully attired as an Imperial bride. Alexios was made co-emperor in 1122 in the same year he married his wife who was crowned with him. This was a huge honor for the Grand Prince of Kiev, who had married into the Imperial family.

John II Comnenos and his wife, the Hungarian princess Piroska-Eirene, were the builders of the a great double church complex in Constantinople. One church was dedicated to Christ Pantokrator and the other was dedicated to the Virgin Eleousa. The church of the Virgin was established as stopping point on the great weekly procession of the icon of the Virgin Hodegetria from her shrine near the Great Palace along the the streets of the city which ended at the church of the Virgin of Blachernae. This procession was one one the great events that occurred in the city, up to 100,000 people participated in it as pilgrims or spectators. When the Hodegetria icon reached the Church of the Virgin Eleuosa it stopped for prayers at the altar, where it was joined by a processional icon of the Eleousa which accompanied it to the Blachernae.

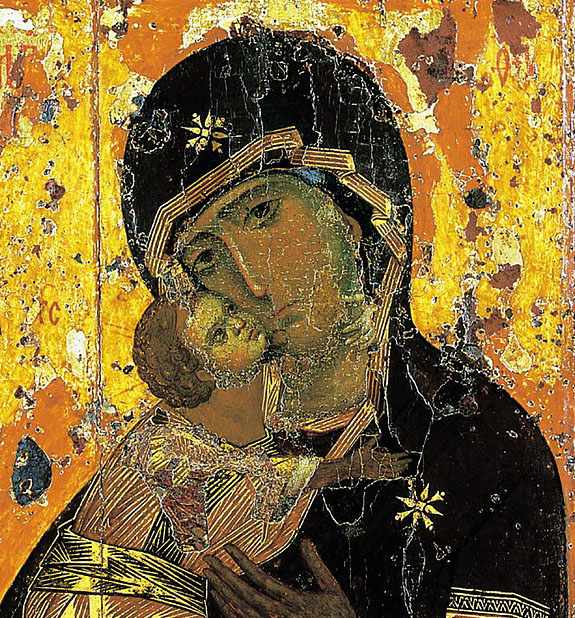

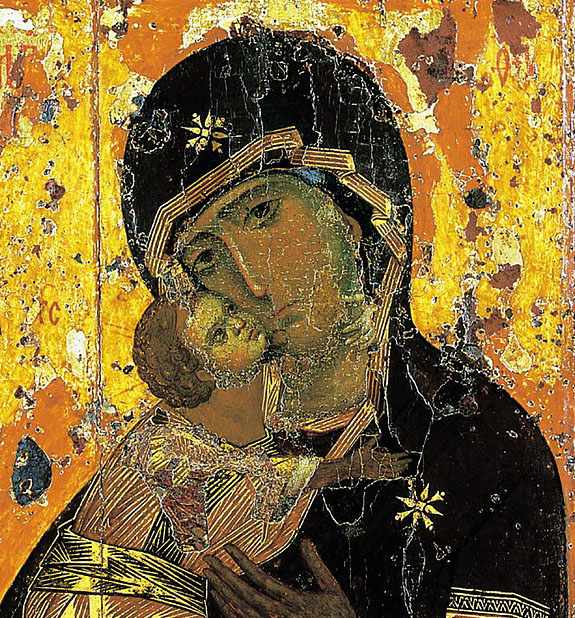

Above is Our Lady of Vladimir as restored in 1918-19, a full view and a close up of the 12th century faces.

Above is Our Lady of Vladimir as restored in 1918-19, a full view and a close up of the 12th century faces.

John II and Piroska-Eirene and their family were deeply devoted to the veneration of this icon and all the members of the family would have carried copies of it with them. The Virgin of Vladimir would have been sent to Mstislav as he was now married into the Imperial family through his daughter. Her husband Alexios was crowned co-emperor with his father and Dobrodeia-Eirene became Empress. John's famous historian-sister, Anna Comnena encouraged her interest in medicine and she translated the works of the ancient physician Galen into Russian. She even wrote her own treatise on medical ointments, which was the first of its kind by a woman author. It's interesting that her brother-in-law, Manuel I, also made his own medical ointments and medicines. Part of Dobrodeia-Eirene's treatise still survives in a manuscript in the Medici library in Florence. Her three Russian sisters were all intellectuals who became Queens of Norway, Denmark and Hungary. She died in November of 1131 leaving a daughter behind.

The face of the Christ-child is very similar to His image in the mosaic of John II, Eirene, Alexios, the Theotokos and Christ in Hagia Sophia. The face of the Virgin could have been painted by the same artist. It is also very close in style to the Kahn Madonna. The faces of the Virgin and child could have been painted by the same artist. You can compare below.

It is also said the icon was ordered in Constantinople in 1131 by the Greek Metropolitan of Russia Michael II, as a gift for Mstislav, who died in 1132. The icon would have traveled on one of the many merchant ships that were moving back and forth across the Black Sea and up river to Kiev. Michael, who came from the cathedral clergy of Hagia Sophia, occupied his see from 1130 until 1145 when he was forced out by Prince Vsevolod Olhovych because of a dispute over local hierarchs. Michael was appointing Greeks as bishops in sees that had been occupied by Russians. When he returned to Constantinople he forbade any Russian bishop to perform services.

It is also said the icon was ordered in Constantinople in 1131 by the Greek Metropolitan of Russia Michael II, as a gift for Mstislav, who died in 1132. The icon would have traveled on one of the many merchant ships that were moving back and forth across the Black Sea and up river to Kiev. Michael, who came from the cathedral clergy of Hagia Sophia, occupied his see from 1130 until 1145 when he was forced out by Prince Vsevolod Olhovych because of a dispute over local hierarchs. Michael was appointing Greeks as bishops in sees that had been occupied by Russians. When he returned to Constantinople he forbade any Russian bishop to perform services.

Right, Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky carrying the icon.

Right, Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky carrying the icon.

In 1155, Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky removed the icon of the Eleuosa Mother of God from Vyshgorod to Vladimir. He had enough of the infighting of the court of Kiev, packed up all of the valuables - including the icon - and packed them off to the north where he established his own principality. Prince Andrei showed great honor to the icon, lavishing an expensive silver and gold covering set with gems and pearls on the icon and placing it in his new Assumption Cathedral, which was finished in 1161. Prince Andrei wanted to transfer the seat of Metropolitan from Kiev to Vladimir but his request was turned down by the Constantinople Patriarch, Luke Chyrsoberges. Transferring the icon from Kiev to Vladimir was part of that effort.

In 1164 the icon was taken into battle by Andrei:

"In that year Grand Prince Andrei with the Greek Emperor Manuel dwelt in peace and love. And it befell them on the same day to go away to war: Manuel [went] against the Saracens; Andrei [went] against the Bulgars, [and] took with him the cross of Christ and the miraculous Vladimir icon of the Most Pure Mother of God, as was always the custom, She being the protectress against enemies, and by prayers to Her the Bulgars were vanquished. And the Russian army, without harm to itself, captured four of their towns and took Briakhimov which is on the Kama. From the icon of the Savior Jesus Christ and His Most Pure Mother was seen a divine light of fire which covered the whole army of the Grand Prince.... Now Emperor Manuel saw this vision at the very same time when a fiery light shined from the icon of the Mother of God"

Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky was assassinated in 1176 in bed by twenty of his "disgruntled retainers" in his beautiful palace of Bogoliubovo. His body was taken back to Vladimir, but the clergy were too scared to conduct his funeral. The city was racked by violence and riots, which miraculously ended when the monk Mikula paraded the Vladimir Mother of God icon around the city. Mikula had helped Prince Andrei move the icon from Kiev to Vladimir. During this time of troubles Prince Yaropolk Rostislavovich, short of cash, removed the precious setting from the icon. It was said that the gold of the covering weighed three pounds. Andrei's younger brother Mikhail restored the oklad and the icon to its place of honor in the Cathedral of the Assumption.

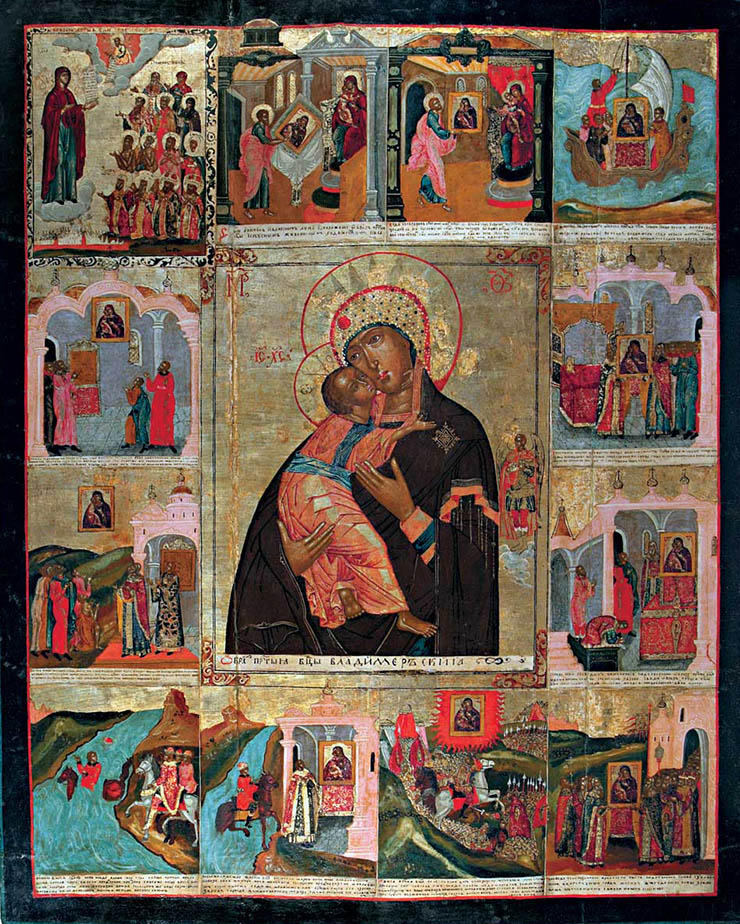

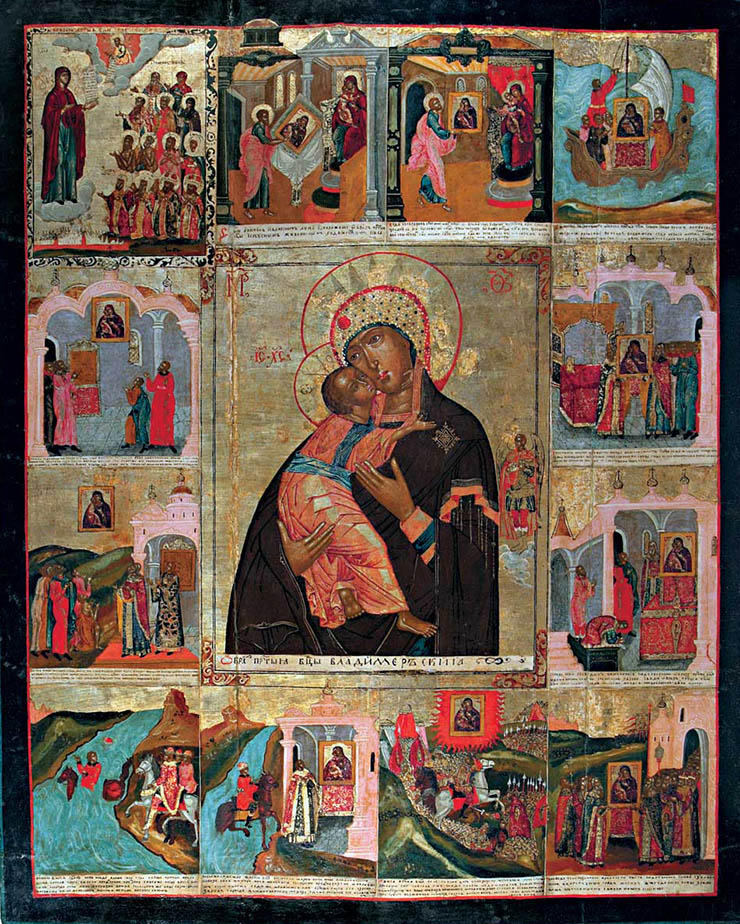

Above is a later copy of the Virgin of Vladimir surrounded by images of the Twelve Feasts. These were modeled in gold on the 15th century Byzantine cover.

Above is a later copy of the Virgin of Vladimir surrounded by images of the Twelve Feasts. These were modeled in gold on the 15th century Byzantine cover.

Another copy of the icon showing scene from the life of the icon including its creative, voyage to Kiev and miracles.

In 1237 the Tatars led by Khan Batu sacked and burned Vladimir, killing tens of thousands of Christians. The Cathedral of the Assumption was looted and burned with people still inside it. The city was destroyed but the brother of the ruling prince who died in the fire, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich survived to assume power. He considered this a miracle through the intervention of the Vladimir Mother of God, whose icon had emerged through the destruction like he did. The Tatars were only interested in the precious covering of the icon, which always had been stored separately from the icon in the sacristy and was taken without damaging the icon. However, it seems the icon was damaged in the sack. The church and the icon were restored by Prince Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, who placed the icon in a new shrine near the royal doors of the iconostasis. This was the first of four major restorations of the icon.

Above is Andrei Rublev's copy of the Virgin of Vladimir dating from around 1408.

Left, the icon arrives at the gates of Moscow.

Left, the icon arrives at the gates of Moscow.

In 1395 the icon was moved from Vladimir to Moscow. Tamerlane was invading Russia and the icon was moved both to protect it and the whole and of Russia from Moscow. Thousands of people greeted the icon when it arrived at the gates of Moscow, the icon was received with this prayer:

"Thou, 0 Mistress Mother of God, hast given all to every faithful people in countless lands who have petitioned for [Thy] favor, and have saved each of them from evil! Thou, o Mistress Mother of God, didst not despise our newly illuminated Russian land. Thou didst promise to remain with we who are humble when Thee, Thyself, Lord manifestly didst send artisans from Constantinople and with gold to raise to Thyself a church in the Pecherskii Monastery which is in Kiev, and Thou didst exclaim, "and I wish to live in Rus' "..... Thou, 0 Mistress Mother of God, today didst make worthy to look at Thy image and bow down to it having trust without fear, we who are unworthy. And thou, [who] as of old didst favor us by moving from Palestine and from Tsargrad, Kiev and from Vladimir to be here with we who are humble now and forever, take pity on us and save us."

The great Moscow Prince Vasilli, had already left the city to face Tamerlane. The Metropolitan of Moscow Kiprian placed the Vladimir icon in the Kremlin Cathedral of the Dormition. A procession was ordered with the icon. On that exact day Tamerlane perished in agony when his retainers poured water that was too hot on him during a freezing cold spell. His stomach burst open! He also had a terrifying dream sent to him by the Mother of God to warn him from attacking Russia. Russia was saved.

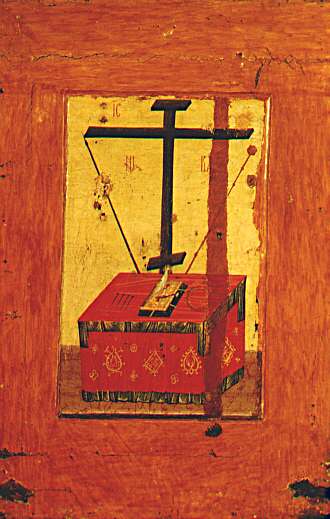

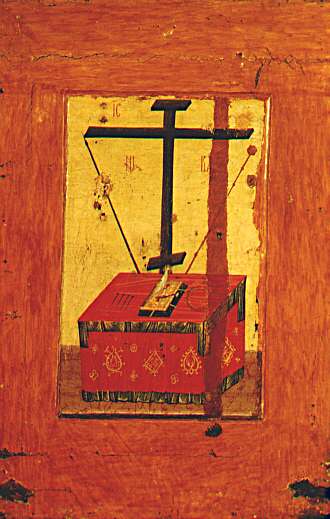

On the left is the painting on the reverse side of the icon.

On the left is the painting on the reverse side of the icon.

Vladimir commissioned the famous painter Andrei Rublev to make an exact copy of the icon to replace the one which had gone to Moscow. This one remained in place until it was removed in Soviet times. It now is housed in the Andrei Rublev museum in Moscow.

There were many times when it was believed the icon had saved Moscow from destruction.

At the same time Andrei Rublev made the copy of the icon for Vladimir he restored the front and the back of the original. His work is plainly visible on the icon today. He completely - and masterfully - replaced the feet of Christ. He replaced the back image, probably of Saint Nickolas, with an icon of the "Hetomasia", a throne with the emblems of the Passion of Christ.

In 2014 the ghostly outline of a bishop was revealed after secret x-rays were taken of the icon. These were the nail holes that attached the basma silver-gilt cover to the back of the icon.

Above is later copy of Our Lady of Vladimir, which duplicates the cover of the 15th century.

Above is later copy of Our Lady of Vladimir, which duplicates the cover of the 15th century.

In 1514 a major repainting of the icon took place, which covered most of it. This renovation was ordered by Vasilii III. A new icon case was also ordered at this time.

Patriarch Adrian paraded it around Moscow in 1698 when he appealed to the emperor Peter the Great to show mercy to the Streltsy after their rebellion. Peter cut off dozens of heads himself with an axe, until he exhausted himself and had to stop. 1200 were tortured and killed.

During the war of 1812 and Napoleon's occupation of Moscow the icon was taken back to Vladimir. It returned to Moscow in 1813.

More interventions took place in 1566, then in the 18th and 19th centuries. All of these took place on top of the original varnish which preserved the original Byzantine painting of the faces. The covering of the icon by its precious decoration obscured what was going on underneath. There was a thick covering of mold, soot and dirt that most have alarmed those who were aware of it. Nicholas II, the last Tsar, was very interested in the history of icons and took great interest in the Virgin of Vladimir. Work was done on the icon in preparation for his coronation in 1896 and also during WWI. In August 1914, Nicholas, his entire family and Grand Duchess Elizabeth (his sister-in-law) prayed before the icon for God to save Russia. The cover was removed this last time before the revolution so that people could venerate the full icon.

From Maurice Paleologue, An Ambassadors Memoirs:

"We entered the Ouspensky Sobor. This edifice is square, surmounted by a gigantic dome supported by four massive pillars, and all its walls are covered with frescoes on a gilded background. The iconostasis, a lofty screen, is one mass of precious stones. The dim light falling from the cupola and the flickering glow of the candles kept the nave in a ruddy semi-darkness.

The Tsar and Tsaritsa stood in front of the right ambo at the foot of the column against which the throne of the Patriarchs is set.

In the left ambo the court choir, in XVIth century silver and light blue costume, chanted the beautiful anthems of the orthodox rite, perhaps the finest anthems in sacred music.

At the end of the nave opposite the iconastasis the three Metropolitans of Russia and twelve archbishops stood in line. In the aisles on their left was a group of one hundred and ten bishops, archimandrites and abbots. A fabulous, indescribable wealth of diamonds, sapphires, rubies and amethysts sparkled on the brocade of their mitres and chasubles. At times the church glowed with a supernatural light.

Buchanan and I were on the Tsar's left, in front of the court.

Towards the end of the long service the Metropolitan brought their Majesties a crucifix containing a portion of the true cross which they reverently kissed. Then through a cloud of incense the imperial family walked round the cathedral to kneel at the world-famed relics and the tombs of the patriarchs.

During this procession I was admiring the bearing and attitudes of the Grand Duchess Elizabeth, particularly when she bowed or knelt. Although she is approaching fifty she has kept her slim figure and all her old grace. Under her loose white woolen hood she was as elegant and attractive as in the old days before her widowhood, when she still inspired profane passions. To kiss the figure of the Virgin of Vladimir which is set in the iconostasis she had to place her knee on a rather high marble scat. The Tsaritsa and the young grand duchesses who preceded her had had to make two attempts - and clumsy attempts - before reaching the celebrated ikon. She managed it in one supple, easy and queenly movement."

For his coronation Nicholas had famous icon painters and restorers, Osip Chirikov and Mikhail Dikarev, restore the image. It was removed from the iconostasis, its covering was removed and the icon was then moved to a private secure workroom in the Kremlin. Both of these painters worked for Nicholas and Alexandra who had many of their icons in their personal collection. They issued a report to the Tsar which said the icon was very dark and obscured by many layers of varnish. They did nothing to it except what was necessary to preserve it from further damage. during their work on the icon another copy replaced it. When they were done the icon went back to the church.

Above is a copy of the icon from 1551 with a beautiful silver cover.

After the Bolsheviks seized power in October 1918 a team of 12 revolutionaries, scientists, art restorers and priests arrived at the Kremlin on December 14th with the order to remove the icon for study. This group included Grigorii Chirikov, the famous art historian Igor Grabar, and a specialist in restoration, Aleksandr Ivanovich Anisimov. The found the icon in dreadful condition, its surface covered with mold and suffering from obvious wood rot. During the revolution the Kremlin had been defended by White Guard cadets. The Reds bombarded the Kremlin and damaged the domes and vaults of Uspensky Cathedral. As a result water and snow poured into the church, doing lots of damage to its contents, especially its iconostasis, kiots and icons. This work of 1918-19 was the last one done to the icon. Chirikov started work on December 20 and began to uncover the various layers of original work and restoration. It came as a great surprise that the faces of Mary and the Christ were the original Byzantine painting of 1130. They had been protected because the oil varnish covering the faces had never been removed and the various layers of egg tempera had been laid on top of it. Other parts of the icon were also found to date from the 12th century. In later centuries other parts of the icon were scraped away to receive new layers of gesso. The restorers left parts of the 15th restoration that was done by Rublev, since these were of both historical and artistic merit. In March 1919 Chirikov finished his work and the first pictures of it appeared. Anisimov and Grabar then founded the Central State Conservation Workshops in Moscow, TsGRM. In summer 1918, Grabar and Anisimov led a series of expeditions to the ancient towns and monasteries along the Volga to study and conserve their icons and frescoes.

In 1918 Patriarch Tikhon blessed the work of Asinimov, Grabar and Georgievsky in studying and preserving icons.

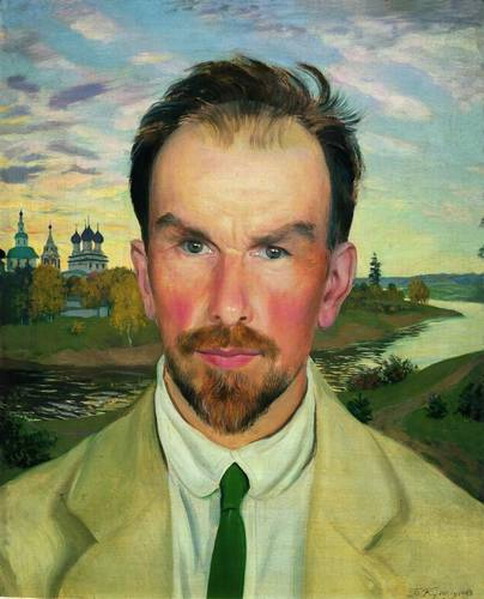

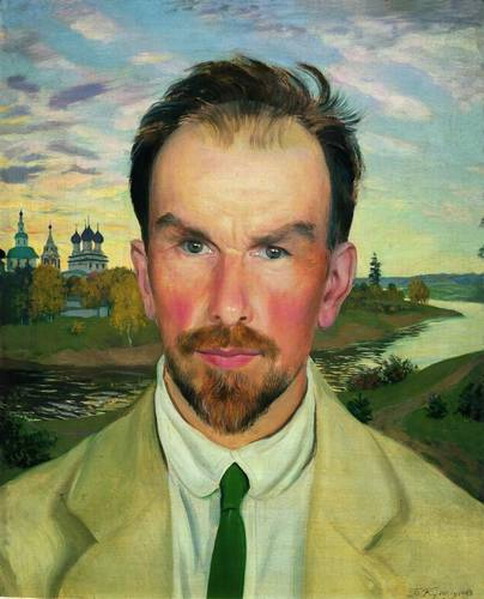

Aleksandr Anismov, painted by Boris Kustodiev in Petrograd, 1915. In the background is the city of Novgorod. After the revolution this portrait was hidden in the storerooms of the Russian Museum until the late 1950s

Aleksandr Anismov, painted by Boris Kustodiev in Petrograd, 1915. In the background is the city of Novgorod. After the revolution this portrait was hidden in the storerooms of the Russian Museum until the late 1950s

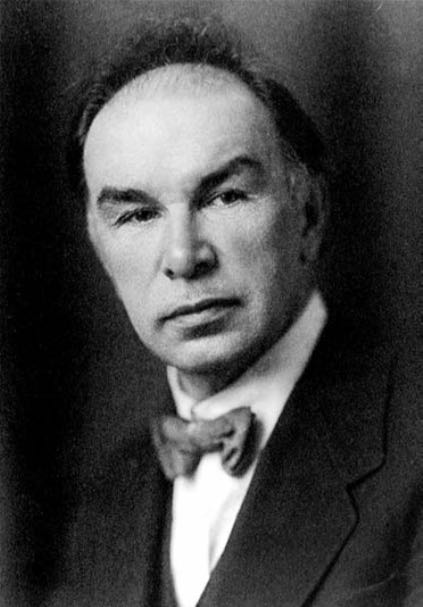

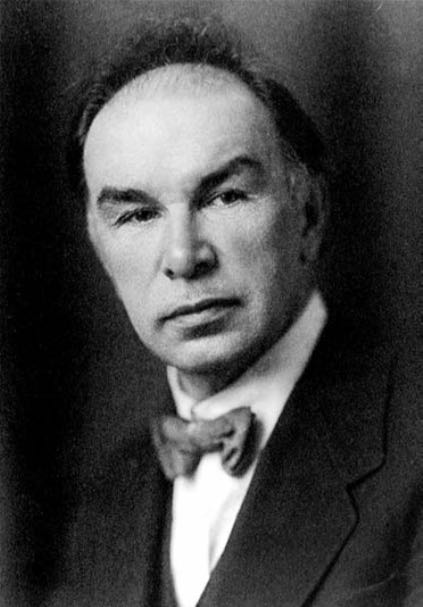

Left, Anisimov in 1929.

Left, Anisimov in 1929.

In summer 1919 Anisimov was arrested as a former member of the Cadet Party by the Cheka at Peterhof and was sentenced to be shot immediately in retaliation for the murder of a CHEKA officer in Petrograd. His life was saved at the last minute by the intervention of an influential freind.

He was described by the director of his institute, Evgraf Konchin, as "an obstinate, impetuous person who did not hide his patience with barbarism nor mince words". He constantly criticized the Soviet authorities for their destruction of old Russian monuments, paintings and icons. This would get him in a lot of trouble later.

In 1930 he was arrested again because his book on the restoration of the icon had been published in Prague by the Seminarium Kondakovianum. He had tried without success to have it published by the Soviet press. He was worried the scientific record of what they had done would vanish forever and took the great risk of publishing it abroad. Indeed, no one would have known the results had it not been published in Prague.

On Feb. 28, 1929, Anisimov wrote to Nikolai Mikhailovich Beliaev in Prague:

“A few words about the exhibition that is currently in Berlin. It cost me dearly, for, first, in quantitative and qualitative terms I put together its base, but Grabar traveled with it, never, of course, dreaming of making for himself a ‘world reputation’ from it, and, second, it stirred up against me here a whole gang of crooks and screamers who joined in one voice to sing about me selling out the pride of Russia, helping the Bolsheviks to make money on this... . It took great effort to stand up to all this and, faithfully and honestly, finish my job: it was my thought that it was time to show the world this great Russian art, to acquaint the world with the Russian soul, enriching its soul with new streams of human goodness, and that it was necessary to give all of you who are cut off from the homeland but who have as much right to it as other Russians a chance to see what is yours and to immerse yourselves in the native source.”

Right, Igor Grabar in 1929.

Right, Igor Grabar in 1929.

The "Berlin" exhibition Asinimov refers to was organized by TsGRM and Igor Grabar of Russian icons on the direct orders of Stalin and Mikoyan. The exhibition traveled to Germany, Great Britain and went all across the United States. The Soviet Government supported it because they hoped to use it to promote the sale of icons and church treasures they had pillaged from Russia's churches and monasteries. The show was a great success in promoting the study of icons, but it did not increase sales. Grabar was forced to resign from TsGRM in part because of this failure.

Grabar discusses the exhibition and its objectives in a 1928 letter to Abram Moiseevich Ginzburg, head of the Antikvariat :

“[We] need to take all measures for the creation of market conditions that will be favorable for the sale of Russian icons... . If the Commissariat of Trade wishes to do really well with icons, we must quickly begin to talk up ‘Russian icons’ and create a fashion for them. ... [T]he оnly reliablе means for this is to publish appropriate books and organise exhibitions.... In this case, therefore, exhibitions must be organized in Berlin, Paris, London and New York and at the same time a well-produced book must be published, with abundant illustrations . . . The exhibition must be held under the banner of our achievements in the field of restoration, and not be simply an exhibition of icons . . . The exhibition must consist both of exhibits of fine museum quality which are to be sent back and of works which are also of high museum quality but which may, after the exhibition has closed ... be sold.”

The selection of which icons would be going abroad was very painful for Russian art historians. Alexei Vasilevich Oreshnikov wrote in his diary in 1928:

“G.O. Chirikov [the restorer of the Virgin of Vladimir] turned up at the Museum along with a Communist whose name was probably Feit (he was English), an architect by training; they were to inspect the icons selected for sale abroad; Grabar came in; we were sitting in the Religious Section, and Grabar told us that the government, primarily Stalin and Mikoyan, had given orders to send the very best icons abroad, and if the museums sent second or third-rate works, then they would go directly to the museums and repositories of icons – the churches and monasteries – and remove all that was best; that would be the end of icons like the Vladimirskaia Bogomater’, Donskaia Bogomater’, Oranta and so forth. These harsh instructions produced a painful impression on Evgeny Ivanovich [Silin] and myself: when Grabar and the others had left, Silin burst into tears. On Grabar’s advice, it was decided not to send icons from the collections of persons living abroad: Zubalov, Yusupov et al.”

In 1931 Asinimov was sentenced to ten years in labor camp. His famous collection of icons and church textiles was confiscated. They took his library, too. Fortunately his first exile took him to the Sovoletsky islands were he ended up restoring the icons and paintings in the churches there. He taught icon history in the camp school. His activities were discovered by the authorities and an important 15th century was smashed in front of him as part of his interrogation, which gave him a heart attack. In 1932 he was then exiled to forced labor on the White Sea-Baltic Canal project in Karelia. Nothing could break his spirit. In August 1937, during the Great Stalinist Terror, Anisimov was sentenced to death for being a “glaring monarchist, fascist sympathizer, and slanderer of Soviet literature and art.” He was shot on September 2.

The state cleared him of all charges in 1989.

In 1930 the icon of Our Lady of Vladimir was given to the State Tret’iakov Gallery and put on public display. In 1931 the TsGRM, the Central State Restoration Workshops and all its branches, were closed and their work terminated. All of the its members who had criticized or complained were sent to camps. Many were shot like Asinimov.

At times the icon became a hot potato being transferred to the authority of different Soviet organizations. During one transfer in 1934 the icon was dropped and damaged. The story has been told that during WWII, in December 1941 Stalin ordered the icon loaded onto a plane and flown around Moscow for several hours in order to protect the city from the Nazis and bless the advance of Soviet forces. The Nazis were stopped just a few miles from the city. It could be true Stalin; was a paranoid narcissist without any religious or ideological convictions. His primary urge was self-preservation.

I first visited the icon in the Tret’iakov Gallery in 1976. When I entered the room where it was displayed I went up to the icon to pray. The elderly women guard saw me walked over to the door and blocked it with a corded drape. She then took my hand, smiled and told me to pray pointing at the icon, we both crossed ourselves. On that same trip I went to Vladimir and visited the Church of the Assumption and saw where the icon originally was. The church was open for worshipers and was packed - what singing! It was my first of 30 visits I made to Russia since then. On my first trip I came back lugging a dozen heavy books on Byzantine and Russian art and history from hard currency stores. These books were expensive - I could not really afford them - but they were impossible to find in the West then.

In 1993 Patriarch Alexis II and mayor of Moscow Luzhkov ordered the icon brought from the Gallery during the democratic revolution in Moscow and displayed in the Epiphany Cathedral at Elokhovo. This was done in hope the icon would deliver the country from anarchy and chaos.

Finally, in 1999 the icon was moved to the Church of St. Nicholas in Tolmachi that was attached to the Tret’iakov Gallery via a tunnel. It this time the first official prayers since the revolution were said in front of the icon. This location and the circumstances of its display a great compromise and has worked out well for the icon. It is displayed in a special case that is monitored by special devices to detect any change in the atmospherics within the case. It is available to scholars and the faithful who want to venerate it.

At right you can see the icon in the Church of St. Nicholas in Tolmachi.

The earliest depictions of the Virgin of Vladimir show it was placed on a three-pronged carrying device. Traces of it can still be seen in the base of the icon today. This holder was mounted in a shrine or kiot of the icon when it was displayed in church. The icon of the Hodegetria in Constantinople had the same three pronged holder that made it easy to carry the icon in processions.

Technical Specifications - How It Was Made

The original measurements are 78cm x 55cm (31 x 22 inches), the size with the outer additions is 100cm x 70cm (39 x 28 inches).

There were merchants who specialized in the sale of icons. There are examples of middle-men who ordered 100-700 icons from a workshop and then took them to Venice and other cities to sell. Icons were ordered by subject, size and style of painting. Contracts show that the icons were expected to take 45 days to produce. Most of the wood panels were made in advance to standard sizes. Many icons were produced in an assembly line like process where workers prepared the boards for painting, others applied the drawings, and painted the robes and backgrounds. The most important and skilled artist did the faces and was expected to do seven faces of the Virgin in one day. There is no way for us to know if Our Lady of Vladimir was produces in such a fashion. We don't know if it was a unique work of art or produced for the open market and exported to Russia as trade. If it was a gift from the Church or Court it could have been bought by a member of the sophisticated clergy of Hagia Sophia from one of the best workshops in the city. They knew where to find first-class style and technique.

It took three months to create the Virgin of Vladimir. One month was needed to prepare the prime the board assuming the panel had been made of seasoned wood. The painting and gilding would have taken two or three weeks. Egg tempera sets quickly and solidly. It is a very stable medium for most colors. Next the panel was varnished and allowed to set for several weeks.

This icon is made of linden wood. Some years after it arrived in Russia it was expanded on all four sides to fit into a larger space, probably a kiot or shrine, using the same type of wood. Besides being carried in processions the icon moved around a lot inside the churches that housed it. Sometimes it was placed in the iconostasis itself. Other times it was hung from the vaults. The board was covered with linen canvas that was attached using fish or rabbit skin glue. The surface was then primed with many layers of gesso that was then smoothed. The gold background was applied and polished using agate or tooth burnishers before the icon was painted. The outline of the figures was usually scratched into the surface of the gesso, but I don't know if this was true of the Vladimir icon. Some artists did not need drawings to trace the figures onto the board. They knew all of the potential subjects of icons very well through experience.

The Painter’s Manual by Dionysios of Fourna, written between 1728 and 1733, provides a description of the process of producing a cartoon from an original icon. The relevant chapter is entitled ‘How to Make a Copy’ and reads as follows:

"Put some black color into a scallop shell with some garlic juice like that which you use for gilding fine lines, and mix them; then go over the forms of the whole figure of the saint that you are copying [...] Then you mix red color with garlic juice and go over the whites of the face and clothes, if you wish taking a third or fourth color and forming the highlights [...] Then wet a sheet of paper the same size as the prototype, and put it between other sheets so that they can absorb some of the water, just ensuring that the paper remains a little moist; then place it on the archetype and press it down carefully with your hand in such a way as not to displace it. Carefully lift up one corner and see if an impression has been left; if it has not, press it a second time more thoroughly. You will thus have made a printed copy in every way identical to the prototype."

One you had a cartoon you could cover the back with black chalk and then prick the outlines through the paper. Many of these drawings survive, they were used over and over again.

A dark green underpainting, called sankir underlays the faces. For this dark undercoat, you mix Constantinopolitan ocher (or more ocher with a little cinnabar) and green, as well as a tiny bit of white. The flesh tones are laid on in layers of yellow-red ochre, ocher comes in two varieties, the Constantinopolitan mentioned earlier and plain, which are reddish and yellowish earth. One had to be careful that the ochre was not too red. It was mixed with cinnibar - vermilion - and lead white to create the flesh tones. The eyelids are drawn in dark red. The eyes are greenish-brown. Lead white highlights have been added.

The style of painting is fused - the modeling is done by a combination of thousands of finely drawn lines and delicate red glazes that can be laid on by broad brushes or even rubbed in by hand. The Virgin wears a cap painted in blue azurite or ultramarine mixed with lead white. Azurite is made of crushed blue glass. Ultramarine is very difficult to mix with water or egg tempera and can take hours of labor to prepare for painting.

She wears a maphorian that was painted in dark brownish-red to imitate imperial purple. All of these colors were easily found in Constantinople and could be purchased in stores along with brushes, pigment grinders and all the other things an artist would need. Some precious colors - like lapis-ultramarine - where sold in measured sizes by the same shops that sold expensive spices and perfumes.

Both the Virgin and Christ Child's clothes were adorned with gold decoration that was added after the painting was completed. To add gilded highlights to an icon, do not put so much egg in the pigment that goes under the gilding, the gold will stick to everything if you do. If you inadvertently put in a lot of egg, tie some silica clay in a cloth and shake it over the place where you want to make gilded highlights. Add cinnabar to the glue and paint as many lines as you want. Once the glue dries, you apply the gold in sheets and blow lightly. Polish it with your tooth or agate burnisher and remove the blank spots with a feather.

Finally the icon is covered with a thin layer of oil as a varnish. The oil is applied by allowing to run down the surface when the panel is tilted. Then the icon is set side in a dust free area and is left to dry.

The technique of painting is very fine and represents the finest Byzantine work of the 12th century. It comes from a workshop attached to Hagia Sophia or the Imperial court. The icon is closely related to the Deesis mosaic in Hagia Sophia and the Kahn Madonna in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C..

There are two surviving covers made for the icon. The oldest one is early 15th century and was made in Constantinople or by Greek goldsmiths working in Russia. It was made at the time of the Rublev restoration. There was a cover made for the icon on the back of a Bishop, most likely Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker. This one has vanished. The golden robe and halo was added in 1657 by Patriarch Nikon. Both of these, the Byzantine cover and the golden robe, are now displayed in the Armory Museum in the Kremlin.

Below is a beautiful copy of the icon by Simeon Feodorovich Ushakov from 1652.

Virgin Enthroned

Virgin Enthroned Mellon Madonna

Mellon Madonna Kahn Madonna

Kahn Madonna The Great Panaghia

The Great Panaghia Hodegetria

Hodegetria The Playing Child

The Playing Child Andrei Rublev Theotokos

Andrei Rublev Theotokos Sinai Theotokos

Sinai Theotokos Hodegetria

Hodegetria Hodegetria

Hodegetria Palaiologian Reliquary

Palaiologian Reliquary Hagia Sophia Theotokos

Hagia Sophia Theotokos Cefalu Theotokos

Cefalu Theotokos Monreale Theotokos

Monreale Theotokos Theotokos Blachernitissa

Theotokos Blachernitissa Nicopeia Icon

Nicopeia Icon.jpg) The Third Rome

The Third Rome

Above is the 15th century Byzantine gold cover (oklad) and 17th century gold clothing-halo of the Virgin of Vladmir. I have restored the painting, the covers are no longer on the icon, they are in the Kremlin Armory Museum. I have used Andrei Rublev's perfect, 15th century copy here. This oklad was brought in 1410 from Constantinople to Moscow by Metropolitan Photius, a Byzantine ecclesiastic newly appointed Metropolitan of all Russia by the patriarch of Constantinople.

Above is the 15th century Byzantine gold cover (oklad) and 17th century gold clothing-halo of the Virgin of Vladmir. I have restored the painting, the covers are no longer on the icon, they are in the Kremlin Armory Museum. I have used Andrei Rublev's perfect, 15th century copy here. This oklad was brought in 1410 from Constantinople to Moscow by Metropolitan Photius, a Byzantine ecclesiastic newly appointed Metropolitan of all Russia by the patriarch of Constantinople.

Above is Our Lady of Vladimir as restored in 1918-19, a full view and a close up of the 12th century faces.

Above is Our Lady of Vladimir as restored in 1918-19, a full view and a close up of the 12th century faces.

Right, Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky carrying the icon.

Right, Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky carrying the icon. Above is a later copy of the Virgin of Vladimir surrounded by images of the Twelve Feasts. These were modeled in gold on the 15th century Byzantine cover.

Above is a later copy of the Virgin of Vladimir surrounded by images of the Twelve Feasts. These were modeled in gold on the 15th century Byzantine cover.

Left, the icon arrives at the gates of Moscow.

Left, the icon arrives at the gates of Moscow. On the left is the painting on the reverse side of the icon.

On the left is the painting on the reverse side of the icon. Above is later copy of Our Lady of Vladimir, which duplicates the cover of the 15th century.

Above is later copy of Our Lady of Vladimir, which duplicates the cover of the 15th century.

Aleksandr Anismov, painted by Boris Kustodiev in Petrograd, 1915. In the background is the city of Novgorod. After the revolution this portrait was hidden in the storerooms of the Russian Museum until the late 1950s

Aleksandr Anismov, painted by Boris Kustodiev in Petrograd, 1915. In the background is the city of Novgorod. After the revolution this portrait was hidden in the storerooms of the Russian Museum until the late 1950s Left, Anisimov in 1929.

Left, Anisimov in 1929. Right, Igor Grabar in 1929.

Right, Igor Grabar in 1929.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints