SAINT GEORGE OF THE MANGANA

All of the great monuments of the Mangana - the name means Arsenal - have vanished. This image of a monastery on Mount Athos can give us a very good idea of what it looked like with its towers, loggias, balconies, churches and gardens mixed together. Here you can see stone, brick and wood construction. Many of the walls are plastered - almost all Byzantine buildings were at the time. The blue color in the center is interesting. That is the color Hagia Sophia was painted in Byzantine times. Churches were often painted that red color you can see on the 6-domed church on the right. The shapes of the domes and their windows on tall drums are very close to those of Saint George, which were gilded. The outside walls of churches were often painted with frescoes or had mosaics on their facades.

All of the great monuments of the Mangana - the name means Arsenal - have vanished. This image of a monastery on Mount Athos can give us a very good idea of what it looked like with its towers, loggias, balconies, churches and gardens mixed together. Here you can see stone, brick and wood construction. Many of the walls are plastered - almost all Byzantine buildings were at the time. The blue color in the center is interesting. That is the color Hagia Sophia was painted in Byzantine times. Churches were often painted that red color you can see on the 6-domed church on the right. The shapes of the domes and their windows on tall drums are very close to those of Saint George, which were gilded. The outside walls of churches were often painted with frescoes or had mosaics on their facades.

The Church of St. George, the Great Martyr and Trophy-Bearer - Tropaiophoros - was consecrated on April 21, 1047 and was very large - the sanctuary was around 120 feet square. That was the same size of the great Katholikon church of the Pantokrator.

The Church of St. George, the Great Martyr and Trophy-Bearer - Tropaiophoros - was consecrated on April 21, 1047 and was very large - the sanctuary was around 120 feet square. That was the same size of the great Katholikon church of the Pantokrator.

On the left you can see an icon of Saint George, who carries his own head in his hand. He had been executed by decapitation and his head was kept in this church encased in gold and pearls for pilgrims to venerate.

The church would have been brightly lit - it had huge windows in the nave and in the apse. Although it the church has vanished we can get an idea of it's decoration by looking at another church built at the same time by Constantine, Nea Moni, on the island of Chios. Here are two pictures of it below. The marble revetment is particularly rich; Constantine Monomachos was really into colorful marbles. Many of the original mosaics survive.

Here is a view into the vaults. This church has a very interesting and unusual layout. The dome is really big. Notice the mosaics in the arched squinches and the inlaid marble frieze. There is a lot of sculpture here in the marble panels at gallery level. The marble revetment incorporates dark purple and blue stones, like an Imperial chamber in a Constantinople palace. Those are expensive materials. Imagine what they would like if they were highly polished. Like Saint George, Nea Moni was a monastery, what an expensive jewel box Constantine created for them!

Here's a view of the iconostasis in Nea Moni. It has been replaced with a simpler one. The plain slab panels and capitals in it make it much too heavy. One capital and part of the original cornice survived. You can see them above the painting of the Theotokos. It is a shame they didn't copy these. The icon on the right side of the center archway of Christ is really nice - I think it is 15th century. Like the walls the floors are set with beautiful marble slabs and opus sectile. Nea Moni is about the same size of Saint George and you can see how bright it was inside. The same workshop of mosaic artists who worked in Nea Moni probably would have worked in Saint George. The church also had a splendid baptistry attached to it.

Saint George of the Mangana was built by Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos who was married to the Empress Zoe in 1042 when he was 42 and the empress was 62. Zoe chose the handsome and charming bureaucrat Constantine to rule with her, and she even allowed him to bring his mistress, the bewitching Georgian Princess Maria Sklerlaina, to court with him and gave her the title of Despina. Constantine intended the Mangana Palace to be his own private love-nest where he could live with Maria in luxury. After she died he brought another mistress, the Alan princess Eirene, to the palace to replace her. Work on the church and palace began when he ascended the throne. When he died 1055 he was buried in his monastery in a magnificent marble tomb. Throughout his life he wore an golden enkolpion around his neck that contained relics that included a fragment of the sword of Saint George.

Michael Psellos, who knew Constantine well wrote:

"In this catalogue of the emperor's foolish excesses, I now come to the worst example of all -- the building of the Church of St. George the Martyr."

"Constantine pulled down and completely destroyed the original church; the present one was erected on the site of its ruins. The first architect did not plan very well, and there is no need for me to write of the old building here, but it appears that it would have been of no great dimensions, if the preliminary plans had been carried out, for the foundations were moderate in extent and the rest of the building proportionate, while the height was by no means outstanding. However, as time went by, Constantine was fired by an ambition to rival all the other buildings that had ever been erected, and to surpass them altogether. So the area of the church and its precincts was greatly enlarged. The old foundations were raised and strengthened, or else sunk deeper. On these latter bigger and more ornate pillars were set up. Everything was done on a more artistic scale. with gold-leaf on the roof and precious green stones let into the floor or encrusted in the walls. And these stones, set one above another, in patterns of the same hue or in designs of alternate colors, looked like flowers. And as for the gold, it flowed from the public treasury like a stream bubbling up from inexhaustible springs."

"The church was not yet finished, however, and once again the whole plan was altered and new ideas incorporated in its construction. The symmetrical arrangement of the stones was broken up, the walls pulled down, and everything leveled with the ground. And the reason for it? Constantine's efforts to rival other churches had not met with the complete success he hoped for: one church, above all, remained unsurpassed. So the foundations of another wall were laid and an exact circle described with the third church in its center (I must admit that it certainly was more artistic). The whole conception was on a magnificent and lofty scale. The edifice itself was decorated with golden stars throughout, like the vault of heaven, but whereas the real heaven is adorned with its golden stars only at intervals, the surface of this one was entirely covered with gold, issuing forth from its center as if in a never-ending stream. On all sides there were buildings, some completely, others half-surrounded by cloisters. The ground everywhere was leveled, like a race-course, stretching further than the eye could see, its bounds out of sight. Then came a second circle of buildings bigger than the first, and lawns full of flowers, some on the circumference, others down the center. There were fountains which filled basins of water; gardens, some hanging, others sloping down to the level ground; a bath that was beautiful beyond description. To criticize the enormous size of the church was impossible, so dazzling was its loveliness. Beauty pervaded every part of the vast creation, so that one could only wish it were even greater and its gracefulness spread over an area still wider. And as for the lawns that were bounded by the outer wall, they were so numerous that it was difficult to see them in one sweeping glance: even the mind could scarcely grasp their extent..."

"People marveled at the size of the church, its beautiful symmetry, the harmony of its parts, the variety and rhythm of its loveliness, the streams of water, the encircling wall, the lawns covered with flowers, the dewy grass, always sprinkled with moisture, the shade under the trees, the gracefulness of the bath. It was as if a pilgrimage had ended, and here was the vision perfect and unparalleled."

BYZANTINE HOSPITALS

The church of Saint George had several free hospitals attached to it, one for the aged, another for the poor, a hospital for homeless migrants and a general hospital for everyone else. One reason Alexius I Comnenus was transferred to the Mangana in his last days, was because his doctors wanted him to be close to the hospital here. There was a pharmacy system in the city and workshops that produced medicines. In the 12th century Manuel I Comnenus himself created new drug compounds to be distributed throughout hospitals in the city, so we can see that hospitals had - for good or bad -the attention of emperors. The Emperor Theophilus established a hospital designed for the healthy exposure to gentle breezes and beautiful views for the benefit of the patients.

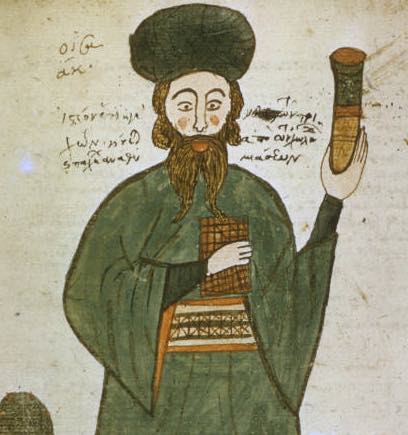

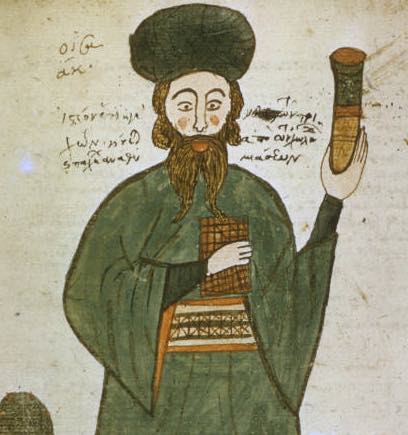

On the right you can see an image of a Byzantine doctor in his official uniform (notice the turban), he is holding medicine in a glass or metal vial. This is a portrait of a real man. He must have been very proud of his forked beard. Doctors would have carried medical handbooks like this.

On the right you can see an image of a Byzantine doctor in his official uniform (notice the turban), he is holding medicine in a glass or metal vial. This is a portrait of a real man. He must have been very proud of his forked beard. Doctors would have carried medical handbooks like this.

Byzantine hospitals were major business ventures, with specialized services and highly professional support staffs. In Constantinople the doctors ran the hospitals, which also had out-patient facilities. Doctors who worked in the hospitals also had their own private practices; they worked for six months in the hospital and the rest of year was free. Doctors were not paid for their work in the public hospitals and were discouraged from accepting tips. Women could be doctors, the famous Princess-Historian Anna Comnena was a doctor who ran her father's 10,000 patient hospital, which was the largest in Constantinople in the 12th century. Anna was a specialist in the treatment of gout. Hospitals had big support staffs. Beyond nurses and orderlies there were cooks, maids, errand boys and people who kept the medical instruments sharp and clean. Indeed, cleanliness was a great concern and there were many laundresses and people who operated water boilers. All of this went on until the end of the empire. We know the Mangana hospitals were still functioning in the mid-15th century.

There was also a famous school of law attached to the monastery in 1047.

Travelers remarked on the beautiful wide court that proceeded the church with its big 30 ft wide columned and domed Phiale - fountain. The church was set right in the midst of the gardens which surrounded it on all sides.

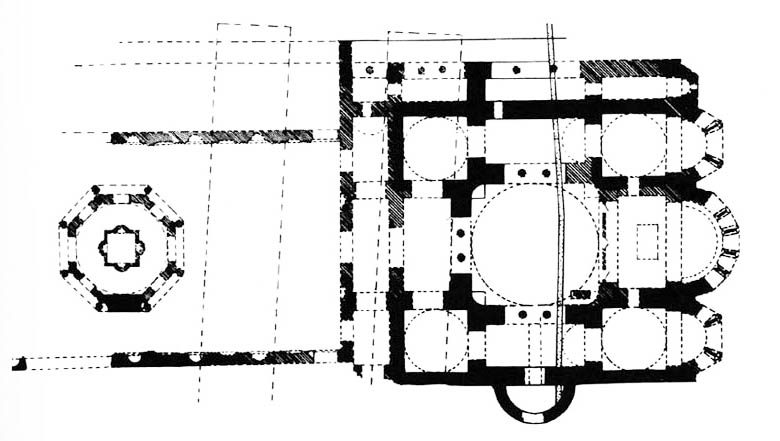

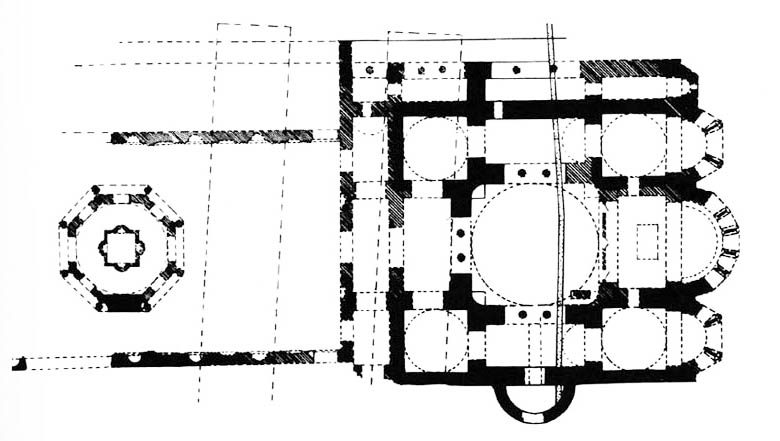

Above is a plan of the church; you can see the great covered fountain to the left in the center of the atrium. Bread was distributed the poor here weekly.

Above is a plan of the church; you can see the great covered fountain to the left in the center of the atrium. Bread was distributed the poor here weekly.

In the 14th century, after his abdication, the Emperor John Catacuzene became a monk by the name of Joasaph and joined the monastery for a time before moving on another one on Mount Athos.

Monastery operations were financed by the properties it owned, real estate in Constantinople, a wheat mill, bakery and vineyards in Thebes. Every year on April 23rd, Saint George's day, the Emperor made a large gift of cash to it.

The Mangana district was not burned in the fires of the Fourth Crusade, but it was pillaged. In the late 13th century and up until the conquest it was a sacred region because of all of the churches and monasteries here and a primary destination for pilgrims because Relics of Christ's Passion were kept here. Because of its position at the very tip of the city and its height, the dome of St. George of the Mangana was a landmark on maps of the city. You can see it in drawings of skyline of the city made by European visitors. It was the last landmark you saw before turning into the Golden Horn.

In 1453 perhaps 100 monks stayed in the monastery and church to protect the patients in the hospitals, the relics, the holy icons and books in their library. When the Muslim troops entered the church they ransacked and looted it first looking for treasure. All of the monks were either killed or sold into slavery. The icons were smashed and the altar was desecrated. It was the end of the monastery. One wonders what happened to the doctors and their patients. There were still 18 monasteries functioning in 1453.

THE MANGANA PALACE

Above is a picture of a room in a 12th century Norman palace in Sicily. It was decorated with mosaics by artists from Constantinople. The walls are covered with marble revetment and there are columns of rare marble set in the corners. This room was planned and built as a copy of similar palace rooms in Byzantium. This is an excellent example to show what a room in the Mangana Palace might have looked like.

Above is a picture of a room in a 12th century Norman palace in Sicily. It was decorated with mosaics by artists from Constantinople. The walls are covered with marble revetment and there are columns of rare marble set in the corners. This room was planned and built as a copy of similar palace rooms in Byzantium. This is an excellent example to show what a room in the Mangana Palace might have looked like.

Constantine IX Monomachos built the Mangana Palace as a harbor where he could find complete rest and absolute tranquility with his mistress and surrounded by his friends. He was criticized for hiding out in the palace to avoid his responsibilities as Emperor. He used the excuse of the building of the palace to spend time with Maria Sklerlaina; he had given her a house that was near the construction site, where he set out food and refreshments for them. After it was built he established an apartment for her there, pretending that she was just another member of the court. Then he abandoned the charade and lived openly with her in public. Constantine built a celebrated great Triklinos - "Hall" in the palace which may have occupied one entire floor. Similar great halls in Byzantine palaces can be seen at Tekfur Saray and the Palace of the Despots in Mistra. This hall would have been a semi-public space that was used in ceremonies and for Imperial banquets. It seems to have had an open air aspect, possibly with great open windows that overlooked the gardens.

Above is another view of the same room in the Norman Royal Palace in Palermo showing the secular decoration of a room in a Byzantine palace.

The wife of the deposed Emperor Nikephoros II Botaneiates, Maria of Alania, moved to the spacious, five-storied, Mangana Palace in 1081, when Nikephoros was overthrown, by Alexis Comnenos, along with her family. Anna Comnena, daughter of Alexis, was raised in the Mangana Palace by Maria of Alania because Anna had been betrothed to her son Constantine. In the end she married someone else.

It was a palace of great luxury, designed for everyday Imperial life, divorced of most of the court ceremonial which was kept to a minimum here. There were great throne rooms and reception halls, but they were of secondary importance to the function of the palace as a type of Imperial in-city resort.

The private rooms were luxurious, with marble columns and sumptuous colored revetments in rare stones. We know from surviving elements from the palace that some column capitals were decorated with the heads of lions and bulls.

The private rooms were luxurious, with marble columns and sumptuous colored revetments in rare stones. We know from surviving elements from the palace that some column capitals were decorated with the heads of lions and bulls.

You can see one of the capitals on the left.

The walls and ceilings were encrusted with beautiful secular mosaics of birds, trees and mythical animals like centaurs and unicorns. The furniture was made of fine woods - the Byzantines were exceptional wood-carvers - and covered with silken feather beds and pillows. These rooms also had tables, desks and chairs for dining and work. Furniture was made to be portable so it could be moved from room to room and palace to palace as needed. Natural light was provided through window shutters with big panes of clear glass. In evenings and at night hundreds of glass oil lamps both single and in big chandeliers provided light. There also were many candlestands, and hand-held candle holders. These lamps burned throughout the night and guided servants and guests on the dozens of staircases and down the many corridors. There were vast closets full of fine silk garments for residents and guests to wear. The rooms were fragranced by incense made from exotic eastern woods like sandalwood and by rosewater.

On the left is an Imperial glass and enamel oil lamp, loot from 1204 now in Saint Mark's in Venice.

On the left is an Imperial glass and enamel oil lamp, loot from 1204 now in Saint Mark's in Venice.

The palace had it's own private baths and internal plumbing. The kitchen was near to the palace in separate buildings. Prepared food would be brought to the palace and 'finished' and kept warm in small kitchenettes. These kitchenettes would also prepare short-order foods like eggs and bread. A Royal had the option of doing this for themselves if they wanted. The palace was kept extremely clean and was thoroughly washed and scrubbed for aesthetic and well as health reasons. For security reasons the servants (often eunuchs) lodged in the palace and there meals there. The court provided everything they needed including their clothes. There were also singers and entertainers who were stationed here when the Emperor of his family were in residence. Priests and clergy would come over from one of the great nearby churches to perform liturgy in the palace chapels. It was state-of-the-art in palaces of the time.

Just prior to the Fourth Crusade the Emperor Isaac II Angelos Comnenos (1185-95) removed some things from the palace - including marbles and a set of great bronze doors - to decorate his own building projects for which he was criticized. We don't know for sure how much damage he did to the palace. He had an excessive obsession with the Archangel Michael and built new - and unnecessary - churches and chapels to him in and around the city. It's possible the two famous gold and enamels icons of the Archangel in Saint Mark's were crusader loot from them.

The palace was noted for it's breezy location and fresh air. You could open the windows on either side of the palace in summer high above the walls and sleep in the cool air from the north wind. The palace was set in gardens and trees so there was the sweet smell of flowers and fresh leaves. It was surrounded with the sound of water from flowing streams and gurgling fountains.

Its secluded location and monastic setting made it the ideal refuge. In his last days the emperor Alexis Comnenus was brought from the Great Palace to the Mangana Palace. The mid-summer heat had been unbearable at the sea-level rooms where he had been staying. His wife had carrying poles added to his bed and relays of men were assigned to carry him. Thus, he was carried up many flights of stairs to the Imperial suite, where he stayed for eleven days in great agony, unable to breathe or eat normally. His family was with him and did everything possible to try and help. Alexis had three primary doctors, Nicholas Callicles, Michael Pantechnes and a eunuch named Michael. They had been with him throughout his last illness, but they failed to be able to do anything. Finally, they carried him even higher to the top floor facing north where there were no buildings up against the palace. In an attempt to relieve his suffering and so he might catch his breath - the windows were all flung open, to no avail. His daughters Maria and Anna (the doctor) gave him rosewater in a last attempt to revive him, which worked briefly. He died at the Mangana on Thursday, August 15, 1118. His son, John II, was proclaimed emperor in the Mangana Palace.

GARDENS OF THE MANGANA

Above is a Byzantine manuscript illumination showing the Evangelist Mark writing his gospel in a flowering garden with fountains and pavilions. The trees sway in the breeze, a metal barrier surrounds the fountain. This could even be the Mangana garden. The walls are plastered and painted in beautiful pastel colors. Mark, who is lost in thought, sits and writes on typical palace furniture of the 10-12th centuries. The gardens are flowing over terraces and there is even a grotto with a marble basin on the lower right. A servant enters the palace through a silken curtain.

The expansive and open gardens surrounding the church and palace gave the area the look and feel of an earthy paradise. The sound of water from the marble fountains added to this impression. The Mangana gardens were semi-public and could be used by members of the court, bureaucrats working for the government, pilgrims and residents of the hospitals. Some of the doctors lived with their families in houses that opened onto the gardens. The monks worked in the hospitals and schools connected to the Mangana so they could enjoy the gardens, too, as they went about their business. They also had their own private garden attached to the monastery. The gardens would cycle through the seasons as trees flowered and then bore fruit. Flowers like lilies, roses and crocus bloomed in season. The roses were planted so different species would bloom right after one another, another extending the flowering season to three months or more. The lawns were cut after the wildflowers planted in them had bloomed. There were many herbs planted here as well. Byzantine gardens were semi-formal in their planting.

Not every palace in Constantinople had a garden. Some were truly urban palaces with no room for them, like the Myrelaion Palace. The appreciation and cultivation of flowers and gardens was an important virtue and an outward sign of being well-educated. Having gardens set with statues, fountains, flowering trees and vines was an accepted way for an emperor to show off both his magnificence and good taste. So, if there was room for a garden next to your palace, you planted one. The Blachernae Palace near the city walls was a 200-room campus of Imperial halls, churches and villas spread out over acres of lawn and flowers. It had one of the most splendid gardens in Constantinople that was also the home to birds, tame deer and water fowl.

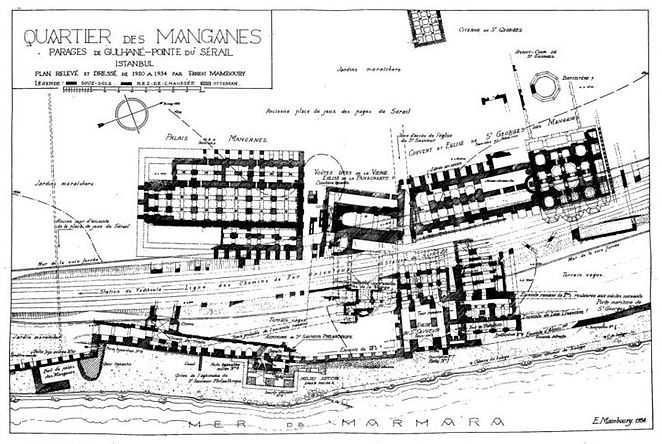

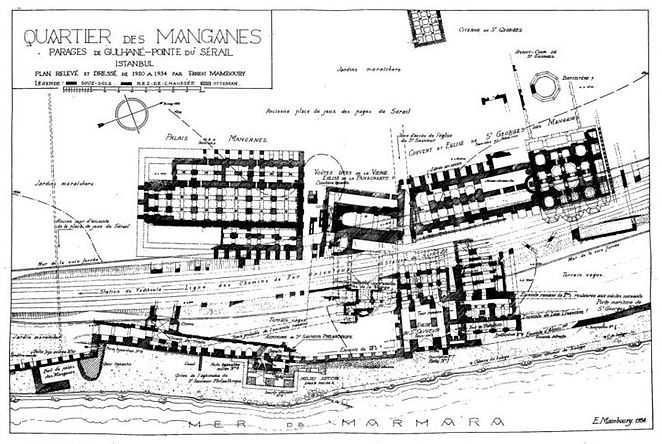

On the left is a reconstruction of the Mangana district of Constantinople. St. George of the Mangana is to the left of center in the picture near the sea. The Mangna Palace is to the right below the that big white church of Christ. It was here on the wall that Our Lord had miraculously appeared, followed by the building of the church.

After the conquest of the city the Saint George of the Mangana stood abandoned for a long time. All of its marbles and columns were removed and used in the nearby Topkapi Palace. The rest of the church was dismantled and used in the building of nearby walls and terraces. All the parts are still there.

MY VISIT TO THE MANGANA

Many years ago I had the honor to spend a day at the site of the Saint George Monastery and Mangana Palace as a guest of the Turkish military. The area is now called Gülhane, which means roses in Turkish. I remember seeing the mist on the grass just as Psellos described it. I met a number of officers and, I think I remember, a general. They were amazingly hospitable; we had lunch followed by sweet Turkish coffee and sweets. I came with a friend, a Byzantinist, who spoke fluent Turkish, which helped. We had permission to rove all over the hillside above the Bosphorus down to the sea wall from the Mangana and then to the Monastery of Hodegetria. We were able to see where an excavation was underway which had earthed a columned doorway in the subterranean level of the palace. I had my Alexiad with me and remembered how Anna Comnena had seen her father die on the top floor of this palace. This was the spot! Anyway, my point in mentioning this visit is that the site of the gardens overlooked the Bosphorus in the most amazing way. You could see ships sailing along the walls and all the way across to the Asia side. Since the ground was flatish. One could visualize the gardens and the ground was covered with a flowering grassy meadow.

Being on the backside of the sea wall one could see the Byzantine buildings that had built up to it and in it. There had been a church in the walls at the exact spot where Christ had be said to have miraculously appeared on the walls. We could also see where the foundations of the apse of St. George of the Mangana had been damaged railway tracks which were cut through it in 1871.

The church and the palace were demolished for building materials to be used in Topkapi Palace. Being a military zone this area was devoid of people and almost free of buildings. What a wonderful and unforgettable day! Here's a plan of the area. You see how the train tracks cut across the apse on the right. The gardens were to the north of the palace and church. In front of the church was an atrium with its famous fountain:

.jpg)

The icon was taken through the city and every week and taken to the Pantokrator Monastery were the icon stayed overnight and was attended by monks in an all night vigil before returning to the monastery, where it was protected by a great red-silk curtain, that was lifted to reveal the icon. The icon was adorned in silver-gilt and, enamels and jewels. These were ripped off after the fall of the city in 1453 and the icon was split into many pieces and burned by the Turks. The icon had been taken to the Chora Church near in the walls in a a vain attempt to protect the city. It was one of the first of the great treasures of Byzantium that perished that day. The last Emperor, Constantine XI, venerated this icon before dying in battle nearby.

The icon was taken through the city and every week and taken to the Pantokrator Monastery were the icon stayed overnight and was attended by monks in an all night vigil before returning to the monastery, where it was protected by a great red-silk curtain, that was lifted to reveal the icon. The icon was adorned in silver-gilt and, enamels and jewels. These were ripped off after the fall of the city in 1453 and the icon was split into many pieces and burned by the Turks. The icon had been taken to the Chora Church near in the walls in a a vain attempt to protect the city. It was one of the first of the great treasures of Byzantium that perished that day. The last Emperor, Constantine XI, venerated this icon before dying in battle nearby.![]() Tradition states that the monastery held the Icon of the Hodegetria, believed to have been painted by Saint Luke. The church of the monastery was a pilgrimage site, where the blind and people with eye disorders came to be healed. The Holy Virgin was said have appeared to there to two blind people, miraculously guided them to the icon and restored their vision. The sanctuary was rebuilt by Emperor Michael III.

Tradition states that the monastery held the Icon of the Hodegetria, believed to have been painted by Saint Luke. The church of the monastery was a pilgrimage site, where the blind and people with eye disorders came to be healed. The Holy Virgin was said have appeared to there to two blind people, miraculously guided them to the icon and restored their vision. The sanctuary was rebuilt by Emperor Michael III.

All of the great monuments of the Mangana - the name means Arsenal - have vanished. This image of a monastery on Mount Athos can give us a very good idea of what it looked like with its towers, loggias, balconies, churches and gardens mixed together. Here you can see stone, brick and wood construction. Many of the walls are plastered - almost all Byzantine buildings were at the time. The blue color in the center is interesting. That is the color Hagia Sophia was painted in Byzantine times. Churches were often painted that red color you can see on the 6-domed church on the right. The shapes of the domes and their windows on tall drums are very close to those of Saint George, which were gilded. The outside walls of churches were often painted with frescoes or had mosaics on their facades.

All of the great monuments of the Mangana - the name means Arsenal - have vanished. This image of a monastery on Mount Athos can give us a very good idea of what it looked like with its towers, loggias, balconies, churches and gardens mixed together. Here you can see stone, brick and wood construction. Many of the walls are plastered - almost all Byzantine buildings were at the time. The blue color in the center is interesting. That is the color Hagia Sophia was painted in Byzantine times. Churches were often painted that red color you can see on the 6-domed church on the right. The shapes of the domes and their windows on tall drums are very close to those of Saint George, which were gilded. The outside walls of churches were often painted with frescoes or had mosaics on their facades. The Church of St. George, the Great Martyr and Trophy-Bearer - Tropaiophoros - was consecrated on April 21, 1047 and was very large - the sanctuary was around 120 feet square. That was the same size of the great Katholikon church of the Pantokrator.

The Church of St. George, the Great Martyr and Trophy-Bearer - Tropaiophoros - was consecrated on April 21, 1047 and was very large - the sanctuary was around 120 feet square. That was the same size of the great Katholikon church of the Pantokrator.

The private rooms were luxurious, with marble columns and sumptuous colored revetments in rare stones. We know from surviving elements from the palace that some column capitals were decorated with the heads of lions and bulls.

The private rooms were luxurious, with marble columns and sumptuous colored revetments in rare stones. We know from surviving elements from the palace that some column capitals were decorated with the heads of lions and bulls.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints