Charles XII, King of Sweden

Charles XII, Turkish Ambassador in Bender

Charles XII, Turkish Ambassador in Bender

Ottoman Sultan Ahmet III

Ottoman Sultan Ahmet III

Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia

Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia

These drawings are extremely important in understanding how Hagia Sophia looked in Ottoman times. Be sure to go all the way to the bottom of the page and see all of the pictures.

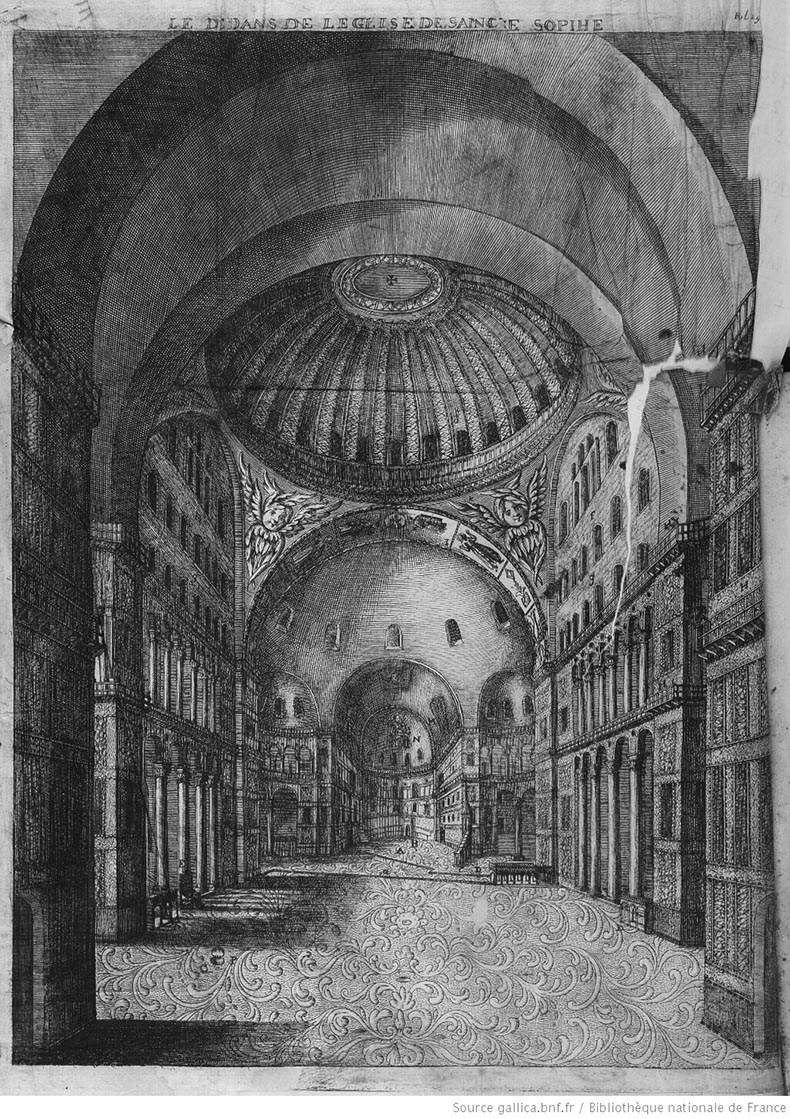

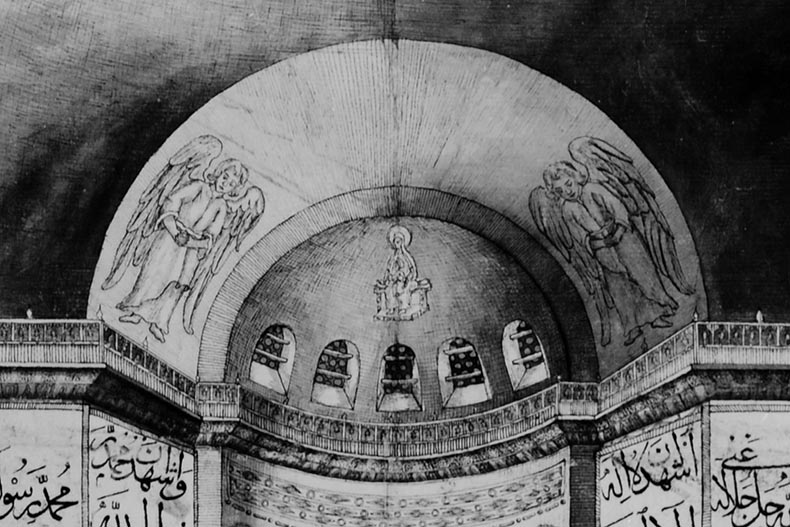

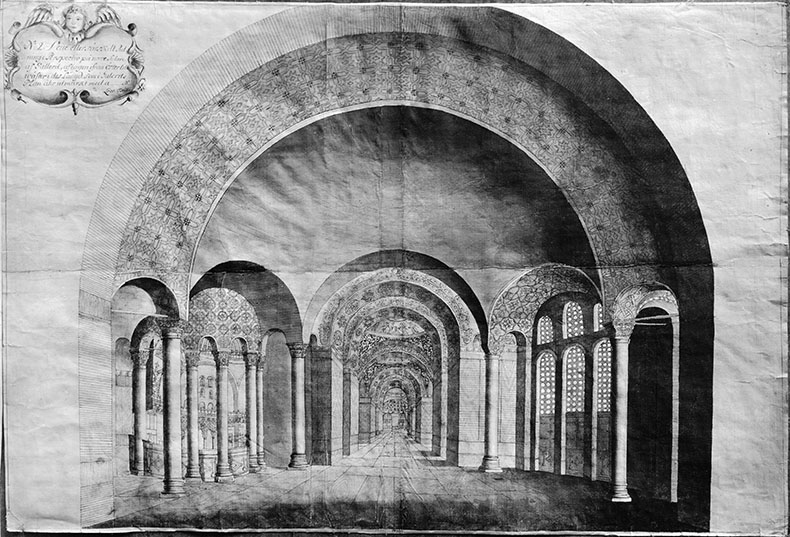

In 1680, Guillaume-Joseph Grelot, an artist-traveler, having spent some time in Constantinople, published a book of his drawings including views of Hagia Sophia. This is his drawing of the nave with a direct view of the apse. 230 years after the Muslim conquest of Constantinople and the mosaics are still to be seen.

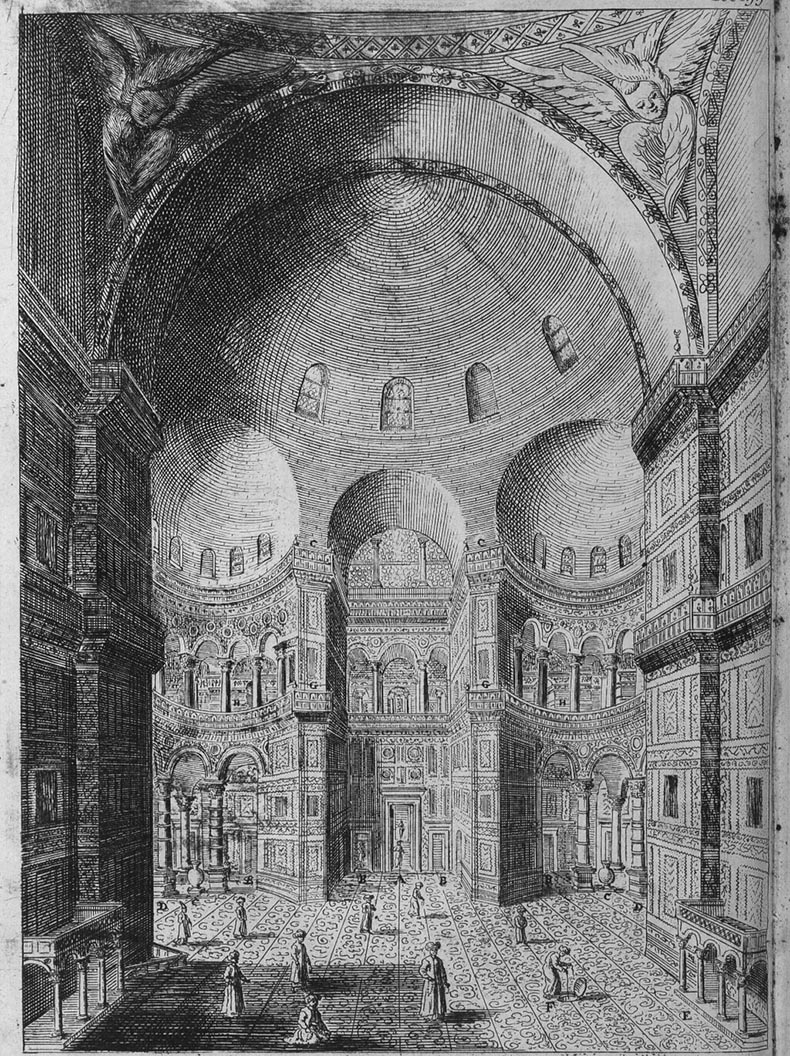

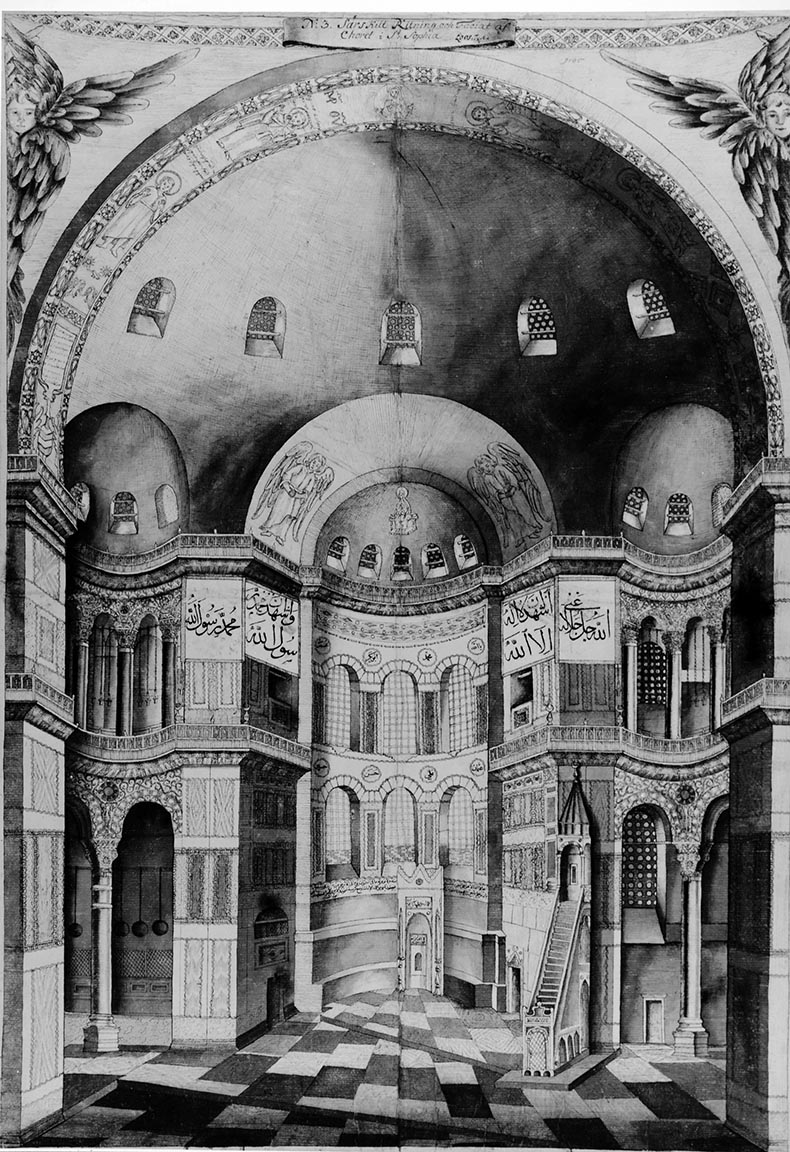

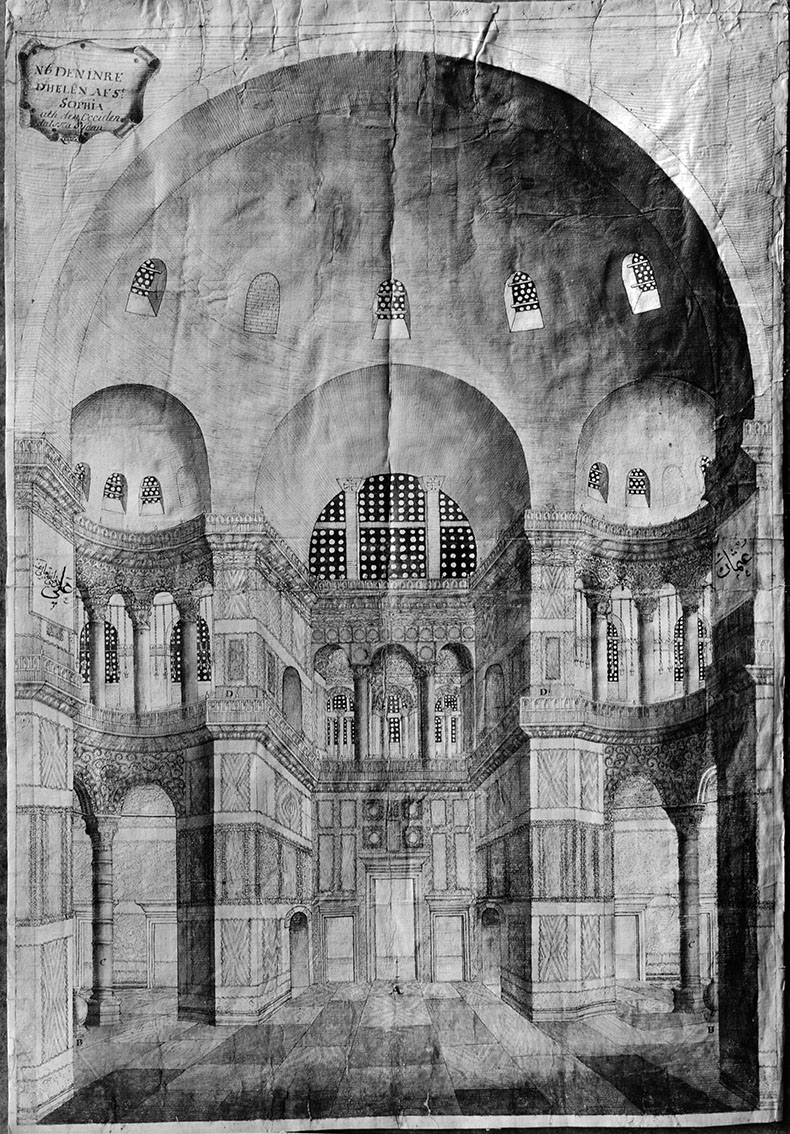

In 1710 Cornelius Loos (1686-1738) came from a humble background; was the son of a Stockholm tavern keeper (that's him on the right). He visited Constantinople where he stayed for around two years and made a series of drawings of the city including Hagia Sophia. He was able to get complete access to Hagia Sophia from Sultan Ahmet III because of his connection to the Swedish King Charles XII. He was trained as a military engineer - specializing in fortifications, hence his skill at drawing and his attention to detail.

Cornelius Loos was one of the young military officers who followed the king into Russia and he was at the Battle of Poltava where Charles was defeated by the Russian Tsar, Peter the Great. After the battle he followed Charles who fled along with the last remnants of his army into the lands of the Ottoman Sultan in 1709, seeking refuge there and an alliance against Russia. Being completely without funds the King became the ward of the Ottoman Sultan and all of his expenses were paid for out of the state budget. Ahmet III was fabulously wealthy and able to afford it. From the Swedish royal headquarters-in-exile (in what is at present is the republic of Moldova), Loos was sent to Istanbul on the King’s orders in 1710. His traveling companions were Conrad Sparre (who had been to Istanbul before) and Nils Gyllenskiepp.

Loos’ mission was to make drawings of the “rarities and monuments” that he would encounter on his journey. As a part of the King's entourage, Loos was living on credit for this entire trip. In Istanbul he was able to lodge with other Swedes who were representing the King at court there. He brought all of his equipment with him. Without any other responsibilities he must have had plenty of time to work on his drawings. The Sultan was a patron of the arts and a scholar; he established the first printing press in Turkey. He would have gladly supported a survey of Hagia Sophia, which was his own personal possession as Sultan. As the personal guests of the Sultan he would have received the red carpet treatment wherever he went. From there his journey continued by boat over the Mediterranean to Egypt and he returned by land through Jerusalem, Damascus, Aleppo, Konya and Izmir, making more drawings, to Istanbul.

Most of Loos's drawings were lost in a fire in Bender in 1713 when there was a Turkish uprising against the Swedish refugees who had taken refuge with the King there. One of the reasons for the uprising were the excessive unpaid debts to local merchants of the Swedes. During the disturbances Charles was captured by the Janissaries and sent to Istanbul under house-arrest.

Out of the drawings that have survived until today, one is from Palmyra, one is of the Tomb of Christ in Jerusalem, two from Rhodes and Bodrum and around forty drawings from Istanbul. Included in his work are three great panoramic views of Istanbul. Most of them are in the National Museum in Stockholm. He was made a noble by Charles XII, got married and had a son who was a military engineer like his father.

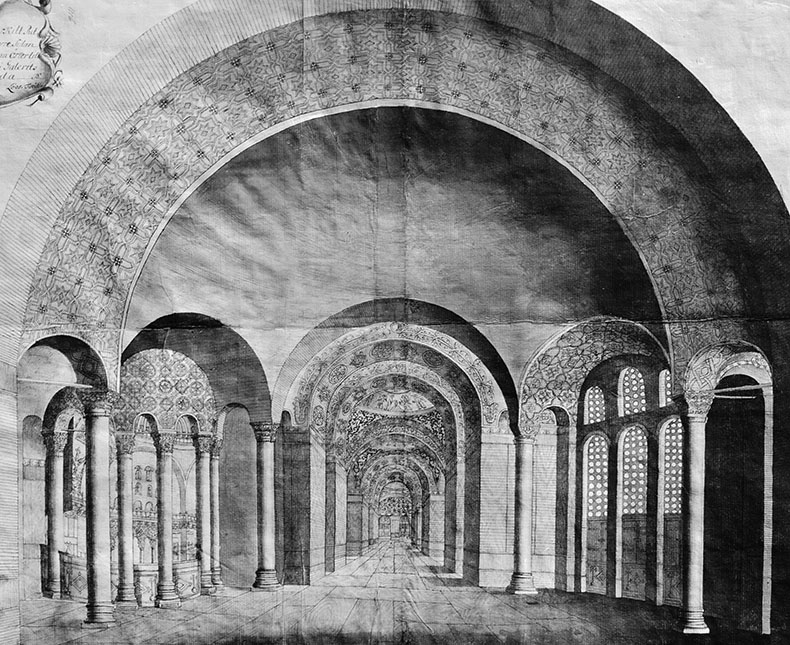

The first Loos drawing below shows the the same view as Grelot above. There are a few mistakes in details of the mosaic figures, but they are not significant. His angels in the bema arch are miss-drawn; he shows them with closed hands when they were holding staffs and orbs. When Loos was here the floor was covered by carpets. The vast eastern vault has plain gold mosaic. The most important thing about these drawings by Loos is that they we done almost 300 years after the fall of the city and the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque. The are an important historical record. The drawings are around 24 x 34 inches and he glued two sheets together for each one.

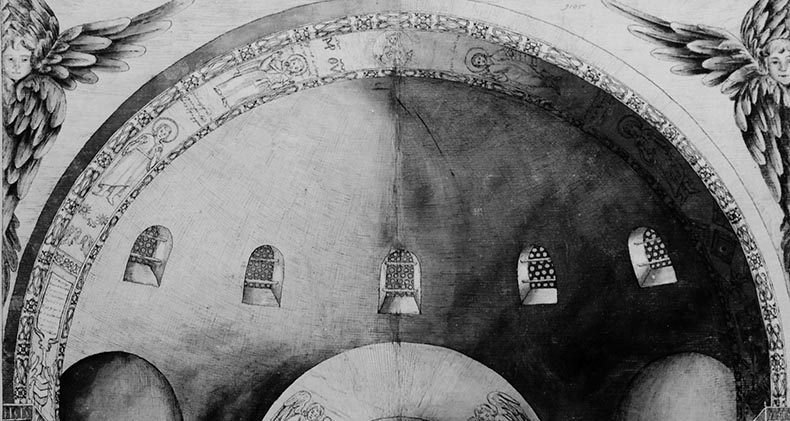

It's interesting that the big apse windows have different fenestration than the other windows. They still have big panes of glass while the other windows have round window glass. Those are the original Byzantine glass panes. The round window glass windows have been described as Ottoman mosque style and this the same type of window was used in churches like Hosias Lukas and Daphni in Greece. This choice of window cuts down the light drastically in the interior. In Justinian's time all of the windows would have had big square glass panes. Thousands of similar panes have been found all over the empire. They have been found in lightly tinted bluish or pale green glass.

It's interesting that the big apse windows have different fenestration than the other windows. They still have big panes of glass while the other windows have round window glass. Those are the original Byzantine glass panes. The round window glass windows have been described as Ottoman mosque style and this the same type of window was used in churches like Hosias Lukas and Daphni in Greece. This choice of window cuts down the light drastically in the interior. In Justinian's time all of the windows would have had big square glass panes. Thousands of similar panes have been found all over the empire. They have been found in lightly tinted bluish or pale green glass.

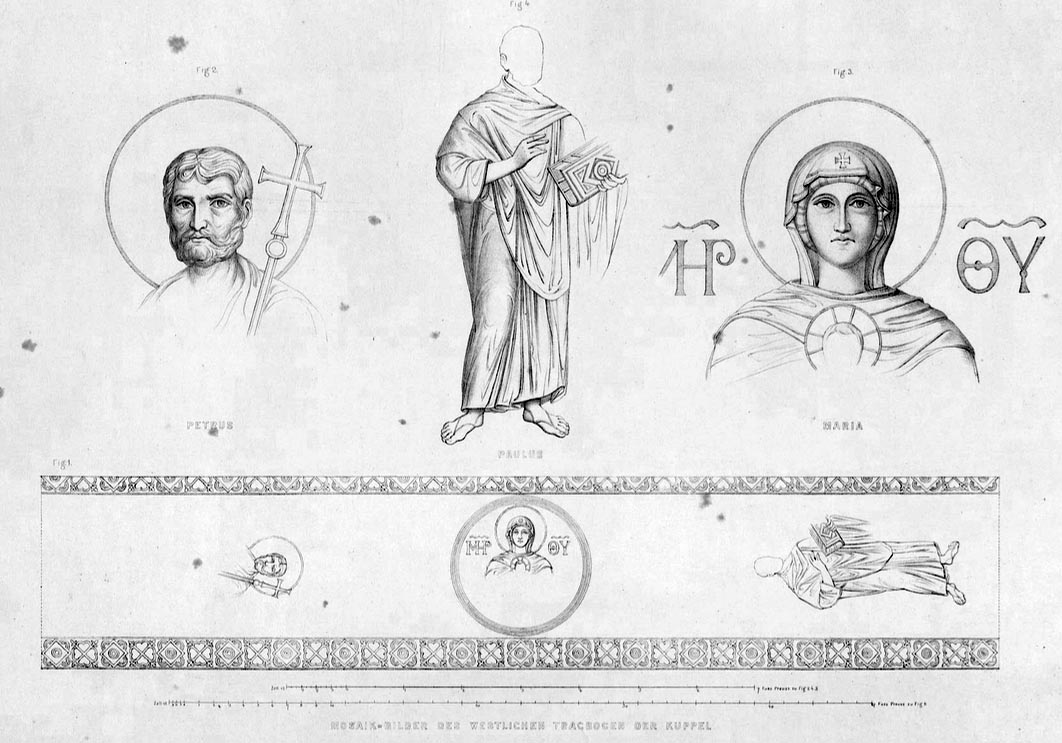

Looking at the eastern arch we can see the mosaics that were added in the 14th century after the repairs made as a result of the collapse of this part of the vaulting. The setting beds of these mosaics remain, but most of the mosaics have been intentionally mutilated and scraped off. All of these figures are gigantic. They consist of Mary the Theotokos in an unusual position oranta position lines from the Magnificat, John the Baptist, the Emperor John V Palaeologus and his wife Helena Kantakouzene. In the center of the arch is an image of the Hetoimasia, the Preparation of the Throne. Below is a view of the western semi-dome and entrance to Hagia Sophia. History tells us were mosaics were added by Basil II in the 10th century. From Saltzenberg (see below) in 1850 we know that there was a giant medallion of the Theotokas and Christ in the summit of the great western arch. On either side were huge mosaic portraits of Saints Peter and Paul. All of this vanished sometime between 1850 and 1930.

Below is a view of the western semi-dome and entrance to Hagia Sophia. History tells us were mosaics were added by Basil II in the 10th century. From Saltzenberg (see below) in 1850 we know that there was a giant medallion of the Theotokas and Christ in the summit of the great western arch. On either side were huge mosaic portraits of Saints Peter and Paul. All of this vanished sometime between 1850 and 1930.

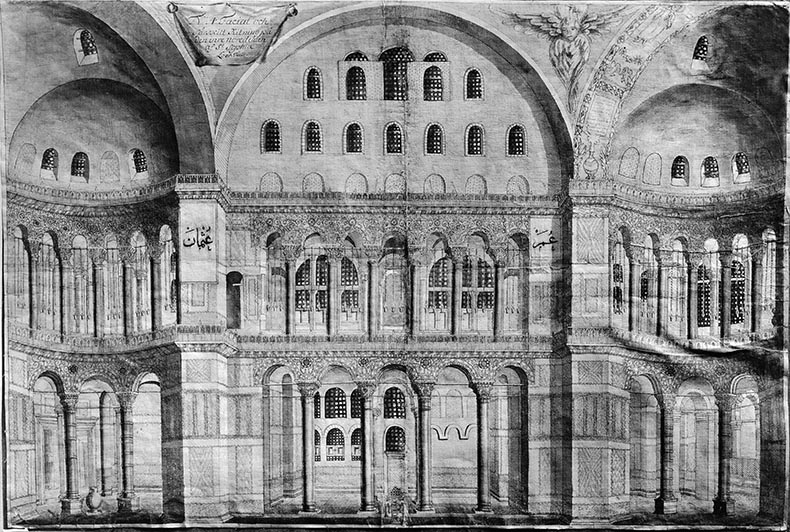

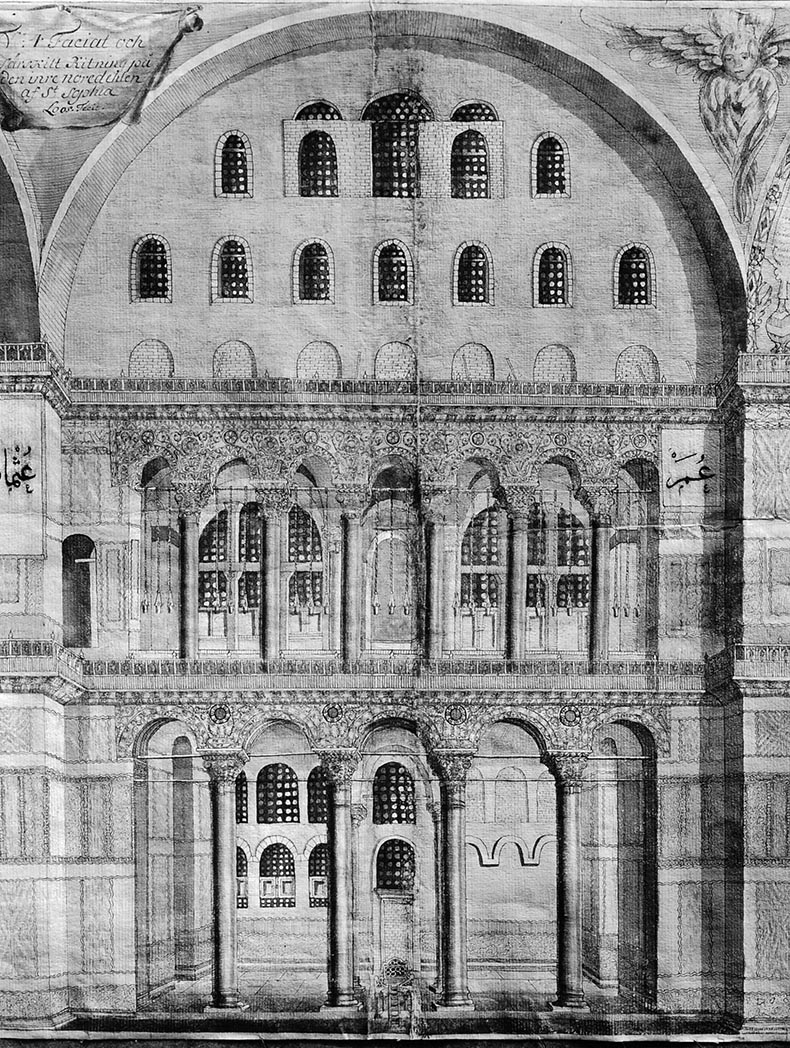

Here is another Loos drawing showing the north side of the church. The mosaics of the tympanum have been painted or plastered over. One can assume this was done during repairs conducted by Sinan in the 16th century when the three windows at the top were strengthened and made smaller. They also reduced the sizes of the other windows here. This, plus the use of the small round windows, would have reduced the daytime light tremendously in the interior.

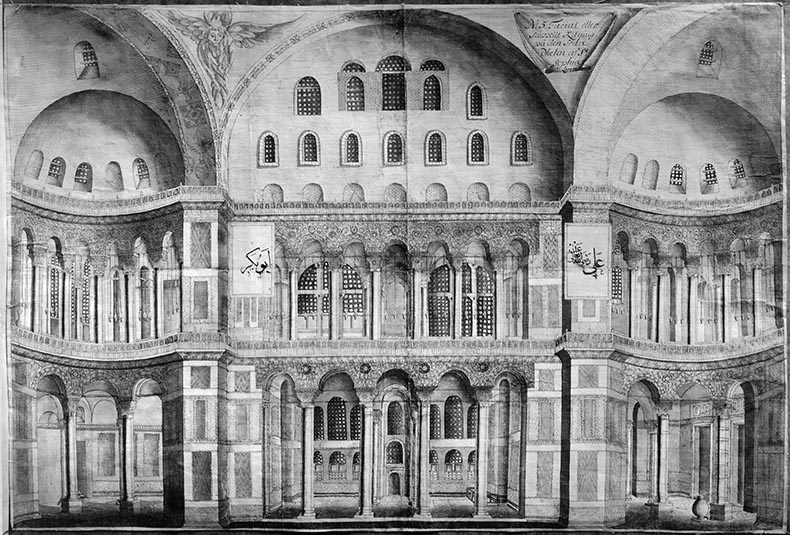

Below is the south side of the nave. There were dozens of figures in the typana that have been covered up - they survived until 1850. Now only a few are left. Loos has placed three glass lights hanging in every arch of the upper arcades. He omits these in his gallery drawings, I wonder why. It took twelve of these lights to produce the light of a 40 watt bulb. They were like twinkling stars in the sky at night, an amazing sight.

Below is the south side of the nave. There were dozens of figures in the typana that have been covered up - they survived until 1850. Now only a few are left. Loos has placed three glass lights hanging in every arch of the upper arcades. He omits these in his gallery drawings, I wonder why. It took twelve of these lights to produce the light of a 40 watt bulb. They were like twinkling stars in the sky at night, an amazing sight.

Next we will look at drawings the galleries of Hagia Sophia in drawings by Loos.

Next we will look at drawings the galleries of Hagia Sophia in drawings by Loos.

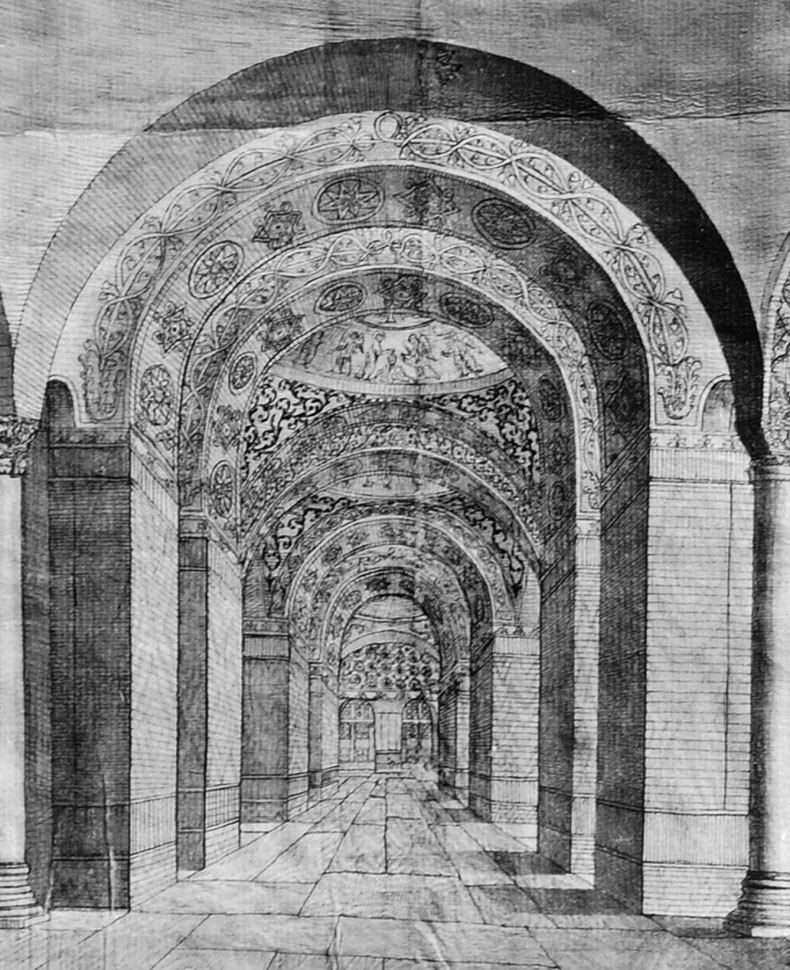

Above is a drawing of the South Gallery by Loos. He used some device - probably the Camera Obscura - to project a view of the south gallery onto a piece of paper and made an exact tracing. The camera obscure was used by many of the most famous artists of the time, including Canaleto. At precisely the time Cornelius Loos was in Istanbul a portable device had been just developed and I am certain he had it with him. "Camera Obscura" is Latin for 'dark room'. It describes an enclosed space with a small hole in one side, sometimes fitted with a lens, through which light enters to form an inverted image of the outside world on a screen placed opposite the hole. The concept of the Camera Obscura was known from at least the 4th century BC, but it was probably not adapted for use as an artist’s aid until the 15th century. An artist could use the Camera Obscura as a drawing aid by tracing the images projected on the screen. The Camera Obscura could be useful for establishing the fundamental structure or perspective of a composition, but the artist still has to translate the projected image into a work of art by making marks on the paper or canvas, which was Cornelius's next step.

Above is a drawing of the South Gallery by Loos. He used some device - probably the Camera Obscura - to project a view of the south gallery onto a piece of paper and made an exact tracing. The camera obscure was used by many of the most famous artists of the time, including Canaleto. At precisely the time Cornelius Loos was in Istanbul a portable device had been just developed and I am certain he had it with him. "Camera Obscura" is Latin for 'dark room'. It describes an enclosed space with a small hole in one side, sometimes fitted with a lens, through which light enters to form an inverted image of the outside world on a screen placed opposite the hole. The concept of the Camera Obscura was known from at least the 4th century BC, but it was probably not adapted for use as an artist’s aid until the 15th century. An artist could use the Camera Obscura as a drawing aid by tracing the images projected on the screen. The Camera Obscura could be useful for establishing the fundamental structure or perspective of a composition, but the artist still has to translate the projected image into a work of art by making marks on the paper or canvas, which was Cornelius's next step.

Sometime later he went back to his drawings and filled in details and drew some parts with rulers and compasses. Maybe he did while he was in Istanbul and he could check his work against the real thing. He decided not to replicate the distortions in the vaults and arches and regularized them. He filled in details of things like cornice around the view of the south gallery. In doing his he made mistakes. Hi drawing shows the leaf cornice wrapping around the entire south gallery and being above the Deesis, where it was not. He filled in mosaic detail in the corrected vaults which required him to make significant adjustments. In doing this we don't know if he filled in areas of lost mosaic, but I think he hasn't, although he has not shown any cracks. In filling in details of the mosaic pattern you can see him being forced to show off-center patterns that we know were in the arched vaults that way here and throughout Hagia Sophia. He has done an excellent job replicating these 6th century motifs without changing or correcting them. I think his biggest challenge was adjusting his depiction the mosaics in the northern arch of the bay here. He must have been perplexed by the difficultly of making this area work in his drawing and his obsession with getting the designs of the mosaics right. I think it is clear that his objections in these drawings was to showcase the architectural details in the sculptures and the vaults as a setting for the mosaics. It is easy to forget that the golden vaults of glittering mosaics was the first thing that impressed European visitors to Hagia Sophia after it's conversion to mosque, followed by the dazzling revetment and columns.

Besides the fact that these drawings tell us the the mosaics of Hagia Sophia were mostly uncovered from view for 300 years after the church was converted into a mosque, they (and Saltzenberg which takes us up to 1850) there is nothing here about what was happening to the Zoe and Comnenian panels. Maybe he didn't have time to do one - or there was less to see and he felt this view covered everything of important. Unfortunately, the museum where the drawings are now housed nothing nothing about their production.

From the drawing we can see that the Deesis was covered over with plaster. We don't know the condition of the Deesis when it was covered over, if it was damaged. We do know that at some point the figure of Mary had water damage. This could have happened before or after the panel was covered over, although it seems to me the plaster must not have been there when it happened. In these drawings we can see the windows are in excellent shape. They are Ottoman-mosque style so they had been switched out sometime post 1453. They would have had to erect a huge scaffold to do this. They did not do anything to the mosaics in the vaults - which would have been easy to do, so I believe someone - a Sultan, obviously - made the decision the have the mosaics and continue to leave them so people could see and admire them. I think, the mosaics on the lower walls had already been damaged by religious zealots and they were covered over to protect them from further damage. Again, here is another attempt to protect them . Could there have been Crypto-Christian converts to Islam who surreptitiously were protecting the mosaics? Were the workers afraid to damage them? Were there secret humanists in the Islamic Ottoman court? Were the mosaics preserved because they had been allowed to survive exposed by Mehmet II, and they were following his wishes? Mehmet II saw himself as the successor of Justinian and the ruler of the great now Muslim Eastern Empire? Somewhere in the Ottoman records I am sure something something will be found to explain this for us and fill in the history of Hagia Sophia as an Ottoman mosque.

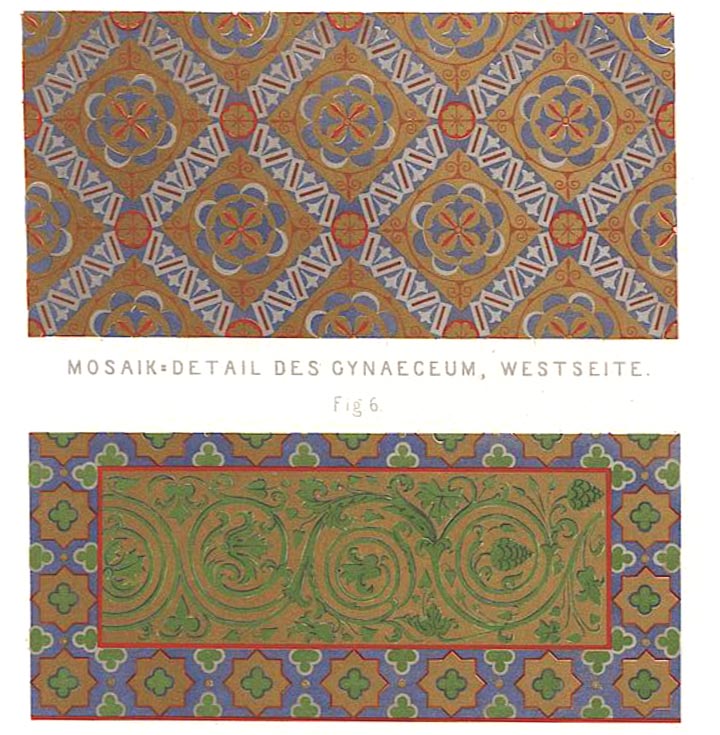

From Saltzenberg in 1850 we can see what the pattern was in golden mosaics of the arch-vault above the Deesis. It's the pattern on top. The other acanthus pattern was in the arches of the arcade.

Above are some Seraphim from the vaults of Cefalu Cathedral in Sicily which were made by artists sent from Constantinople that are very similar to those Loos has drawn in the South Gallery. Here you can see two-toned blue wings and golden eyes.

Above are some Seraphim from the vaults of Cefalu Cathedral in Sicily which were made by artists sent from Constantinople that are very similar to those Loos has drawn in the South Gallery. Here you can see two-toned blue wings and golden eyes.

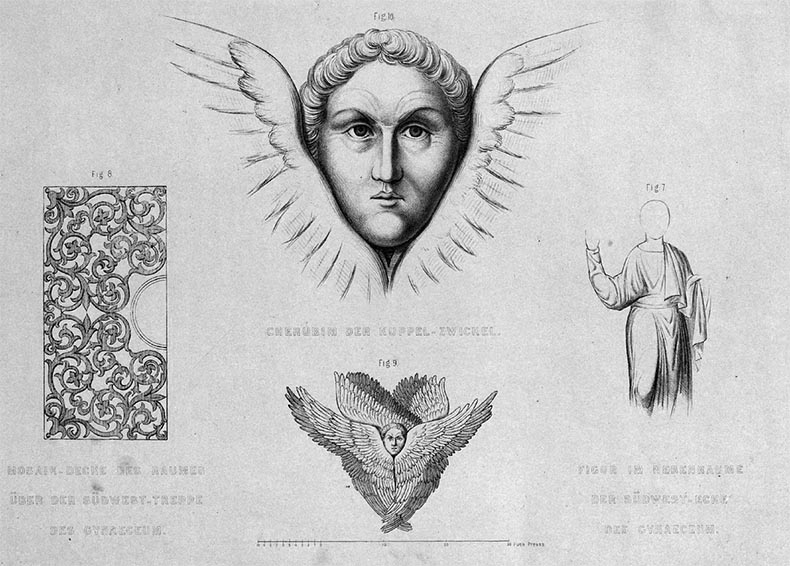

Cornelius's drawings show us the South Gallery was not dominated by the Deesis, but by the figures in the most easterly vault. This vast golden field of mosaic was filled with gigantic four-winged Cherubim and six-winged Seraphim. You can just see the tips of the wings of the Seraphim on the right and left. These angels are huge - at least twice life-size, perhaps 12 feet tall. The hands of the Cherubim were extended outwards and their wings are covered by eyes. The wings of the Cherubum were made of blue glass mosaic cubes and the eyes were drawn in gold. The flames were in orange and a darker red, the color of glowing coals. The faces would have been in natural flesh tones. There are fires in the corners of the vaults with white chariot wheels set with eyes. In the Old Testament figures of Cherubim decorated the sanctuary, by the decree of God Himself. Here they are in the vault closest to the sanctuary of the church. Looking outside of the South Gallery into the nave of Hagia Sophia these Cherubim join with the Seraphim in the pendentives of the nave in worshiping God and defending the throne of God. Imagine what it would have been like when the choirs of the church were singing the chant of the Cherubim during liturgy. It would have felt like the angels were actually there and participating in the service. Those shimmering white wheels with eyes are Ophanim, part of the throne of God. In Ezekiel we read of his vision of God:

"one wheel upon the earth by the living creatures, with his four faces. The appearance of the wheels and their work was like unto the color of a beryl: and they four had one likeness: and their appearance and their work was as it were a wheel in the middle of a wheel… As for their rings, they were so high that they were dreadful; and their rings were full of eyes round about them four."

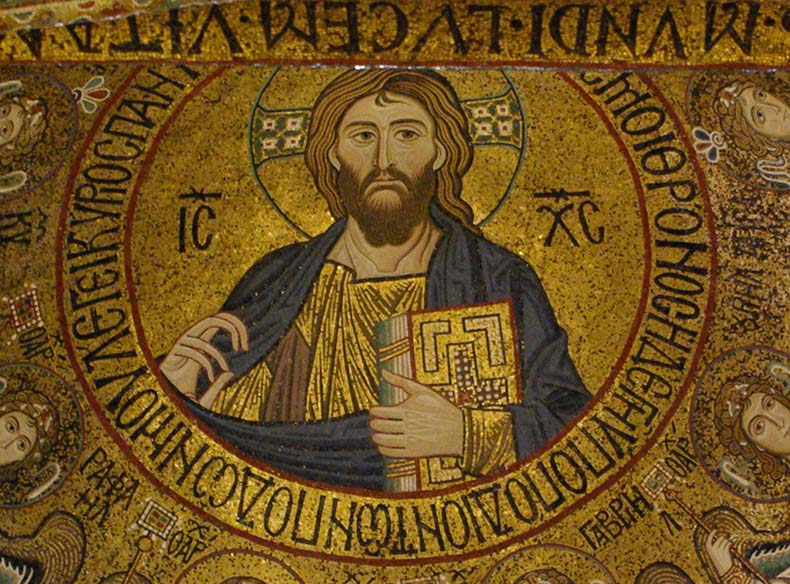

In the center is a larger than life circular medallion of Christ Pantokrator in a multi-colored rainbow-like pattern. Below it you can see the terrible watercolor Fossatti made of it around 1845.

Above is an image a similar mosaic Pantokrator in a dome of the Capella Palatina in Sicily. This mosaic was made by Comnenian artists from Constantinople.

Above is an image a similar mosaic Pantokrator in a dome of the Capella Palatina in Sicily. This mosaic was made by Comnenian artists from Constantinople.

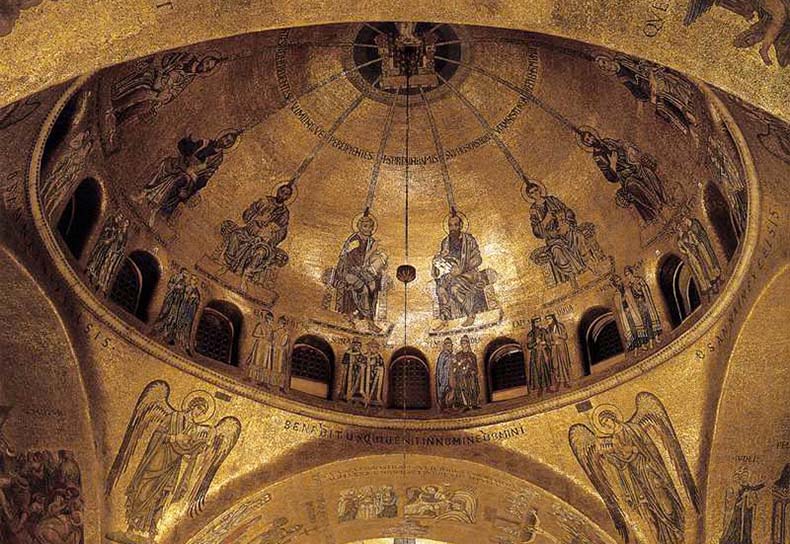

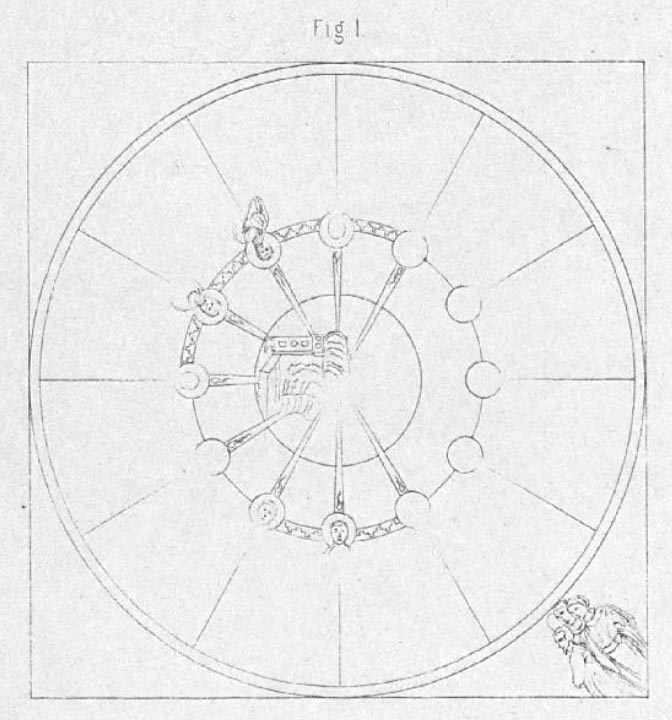

In the next vault, the one over the Deesis, there is a mosaic of Pentecost - the Descent of the Holy Spirit, a feast of the Orthodox church. The mosaic was a virtual, 3-d representation of the event. Standing beneath it you are right the center of the event. Above is a mosaic of the of the room in which the Apostles were baptized in the Holy Spirit and spoke in tongues. This would have been an appropriate subject for this space - councils of the church were held in this part of the South Gallery. In the center of the vault we can see a circular image with two feet, which are the feet of a throne. Here was an image of Christ on a blue circular field seated on a lyre-back throne. Below is a picture of a dome from St. Mark's in Venice that has a similar scene of Pentecost, which must have been a replica of decoration in Hagia Sophia. In the Loos drawing we can see is is sketchy about the figures in the pendentives. The angels we see in Saint Mark's would go perfectly there. below this picture is another Byzantine mosaic Pentecost from Hosias Loukos in Greece. This one has people in the pendentives representing the nations the apostles would be preaching to.

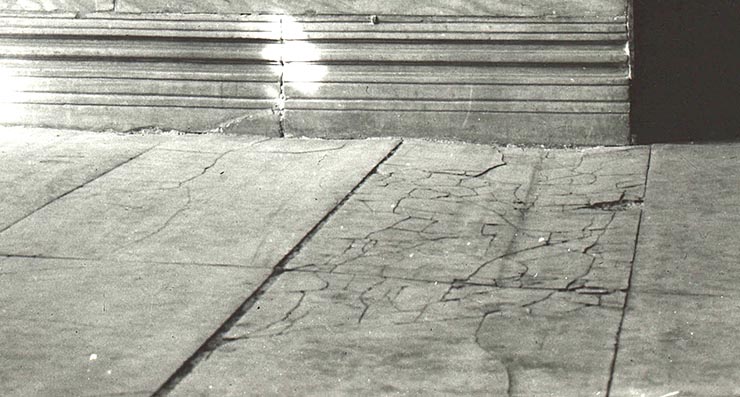

Above, on the left you can see a mysterious carved marble parapet. It is about 3 ft tall and originally extended all of the way to the column. This parapet had three panels in it from a chancel screen with different patterns. This could also have originally been the front of an altar. It is thin and braced from the back with a bronze or brass brace. there were several these in back and you can still see the their marks in the pavement. The marble floor is really messed up on the other side of the pediment with cracks and marks of things that were attached here. There once was a big candle stand further in. This barrier closed off the area of the Deesis with out obstructing a visitors view of it. It actually forces you to look at the Deesis at a certain angle which mysteriously corrects some of the distortions in the the face. This means the mosaic was always meant to be viewed from the right. This view - in raking light - shows-off the pattern in the gold background. That gold pattern is like a gold lampas silk fabric. Around this time the Byzantines had perfected the technique of subtle lampas weaves in silk. Perhaps there is a connection.

Above, on the left you can see a mysterious carved marble parapet. It is about 3 ft tall and originally extended all of the way to the column. This parapet had three panels in it from a chancel screen with different patterns. This could also have originally been the front of an altar. It is thin and braced from the back with a bronze or brass brace. there were several these in back and you can still see the their marks in the pavement. The marble floor is really messed up on the other side of the pediment with cracks and marks of things that were attached here. There once was a big candle stand further in. This barrier closed off the area of the Deesis with out obstructing a visitors view of it. It actually forces you to look at the Deesis at a certain angle which mysteriously corrects some of the distortions in the the face. This means the mosaic was always meant to be viewed from the right. This view - in raking light - shows-off the pattern in the gold background. That gold pattern is like a gold lampas silk fabric. Around this time the Byzantines had perfected the technique of subtle lampas weaves in silk. Perhaps there is a connection.

Below is a picture of the floor to the left of the location of that screen. You can see the floor is really messed up. It looks like there was a thicker marble parapet there for very long time that was removed and replaced with thinner one. There are many marks in the floor in front of the Deesis that are unexplained. It looks like this is an original slab that has almost 1600 years of wear and tear in it.

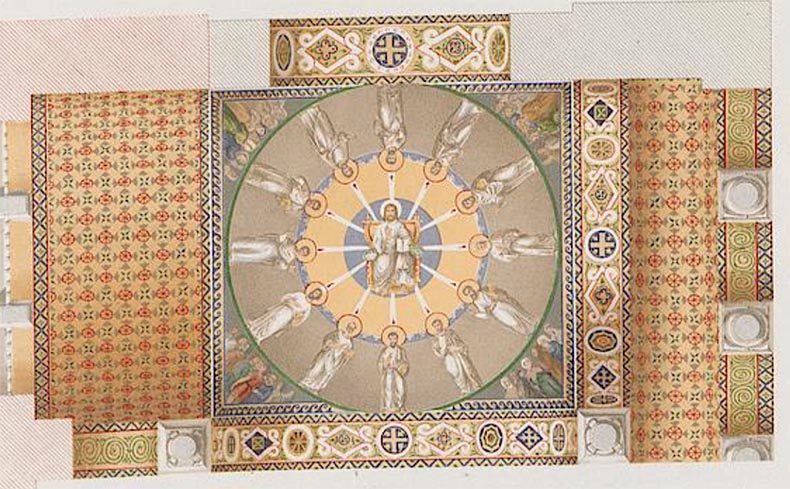

Another observation - the crosses on the marble screen were not damaged when the drawing was made. The furthest vault has a geometric design. Tongues of fire fall from the Holy Spirit to the heads of the apostles - they gesture with their hands in different ways - indicating they are speaking in foreign languages and preaching the Gospel. Although they were not present, Paul is usually added along with Mark and Luke. All of these figures would have been life-sized. From the drawings of Salzenberg we know mosaics in the vaults survived until at least 1850. It is impossible to know to what degree since Salzenberg restored missing parts of the Pentecost. From DOAKS -"Since the Fossati Brothers were already in Hagia Sophia in 1847, it seemed like a golden opportunity to draw this lovely building and some of its newly uncovered mosaics. So Salzenberg was sent by the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV to document the building, especially the ornamentation, to bring back ideas for the king to use when designing new buildings in Prussia." Here are drawings and watercolors he did of the dome and vault mosaics of Pentecost with details of the figures. There are many differences with Loos. Saltzenberg has the mosaics in the arches much better. He does a great job showing us that the carpet mosaics in the right and left vaults match (the right one has survived). Saltzenberg shows the Apostles standing and we see that Mary is with them. Saltzenberg shows no architecture behind the apostles. That's a big difference.

Tongues of fire fall from the Holy Spirit to the heads of the apostles - they gesture with their hands in different ways - indicating they are speaking in foreign languages and preaching the Gospel. Although they were not present, Paul is usually added along with Mark and Luke. All of these figures would have been life-sized. From the drawings of Salzenberg we know mosaics in the vaults survived until at least 1850. It is impossible to know to what degree since Salzenberg restored missing parts of the Pentecost. From DOAKS -"Since the Fossati Brothers were already in Hagia Sophia in 1847, it seemed like a golden opportunity to draw this lovely building and some of its newly uncovered mosaics. So Salzenberg was sent by the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV to document the building, especially the ornamentation, to bring back ideas for the king to use when designing new buildings in Prussia." Here are drawings and watercolors he did of the dome and vault mosaics of Pentecost with details of the figures. There are many differences with Loos. Saltzenberg has the mosaics in the arches much better. He does a great job showing us that the carpet mosaics in the right and left vaults match (the right one has survived). Saltzenberg shows the Apostles standing and we see that Mary is with them. Saltzenberg shows no architecture behind the apostles. That's a big difference.

He also tells us that these mosaics in the South Gallery could be easily seen from the nave and how beautiful they were shining in the sunlight pouring into the church. It's one of the few comments he made showing an emotional response to what he was seeing so he truly must have been impressed. His reaction echos other travelers from much earlier times who visited the church and commented on the magnificent, sparkling, golden vaults.

Saltzenberg tells us that:

"A repair of the church of St. Sophia in 1847 and 1848, which made it possible to examine it in more detail, prompted the order of His Majesty the King for my journey to Constantinople. I found the building full of scaffolding up to the highest dome top and the technical direction of the restoration work in the hands of prudent and meritorious architect Fossati; The scaffolding, preferably calculated to rid the highly interesting mosaic work on the vaults of their old whitewash, facilitated any desirable examination and measurement I wanted to make, and the obliging kindness of Mr. Fossati, who with a lively sense of art gladly supported any artistic research. I owe the privilege of being able to carry out the necessary work without considerable obstacles;"

He was not able to see all of the mosaics that were exposed. In particular he notes of one the great angels in the bema arch which had been described to him, but couldn't manage to see. The mosaics were being uncovered and recovered up fast and he simply missed seeing some. The following is his description of the mosaics in the vaults of the section of the gallery where the Deesis was. It's funny that he doesn't mention the Deeis, we have ghastly watercolors of it by Fossatti from the time of his visit. He doesn't mention the mosaics of Constantine and Zoe or John II and Eirene. Maybe they hadn't been uncovered yet, out the were obscured by scaffolding. So we can't be sure what else survived here other than what he describes. He eagerly got into the rooms of Hagia Sophia that were attached to the gallery on the south side what had been a part of the Patriarchal Palace and both describes and illustrates the mosaics he saw there.

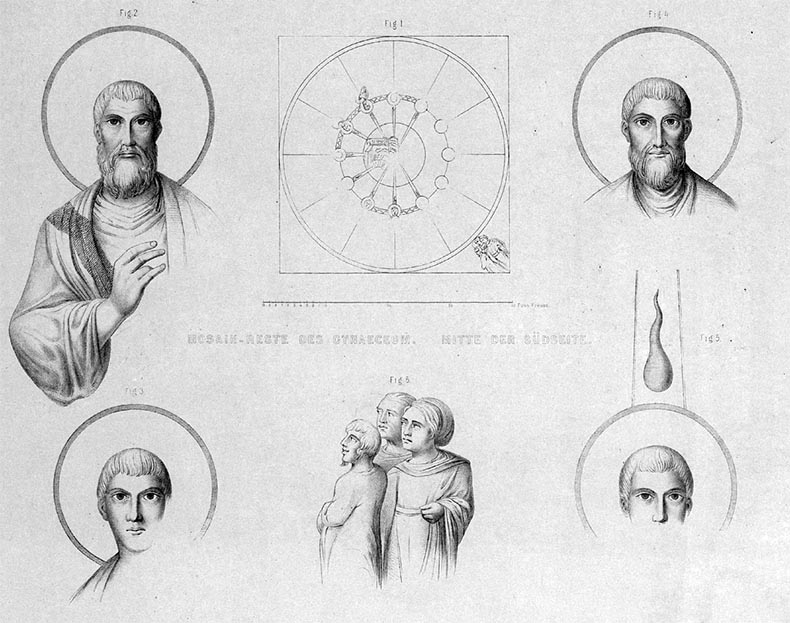

"Pictures of the Women's (south) Gallery. The domes of the Gynaeceum, seem to have contained representations of the New Testament; only one of them, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit over the twelve apostles, has remains, (he was not able to see anything else while he was there)... ( I have illustrated) the remains of the apostles on a larger scale, the individual heads are 1 foot 2 inches high. The garments are bright off-white with silver highlights, the strip indicated darker in Fig. 2 is half red, half blue. Behind the apostles was a brown field, the upper edge of which was decorated with a meander, half blue and half red. Only a part of the throne in the middle was preserved, on it is a green cushion and hanging down a piece of blue robe with gold ornaments. The illustration on page XXV. Fig. 1. is a restoration, from which the arrangement of the colors can be seen, with the exception of the picture of Christ, which is from the illustration sheet XXVII. is borrowed. Fig. 6. Sheet XXXI. illustrates the part of the surviving people in the cupola-vaults who are witnesses to the scene of Pentecost; striking is the characterization of the lower people as opposed to the noble apostles. If, standing in the middle of the room, one looks at this dome, then the apostles seem to stand upright and the light-gray rays with the red fiery tongues come out of the sky on them to shoot down."

Below is another drawing by Salzenberg. At the top is a drawing of a Seraphim's face. Below that on the left is a drawing of the mosaic in a room over the stairs to the gallery, next to the right is another drawing of a Seraphim (this is a drawing of one of the great seraphim in the pendentives), finally to the far right is an image of Christ from the corner of a side-room of the South Gallery.

Below is another drawing by Salzenberg. At the top is a drawing of a Seraphim's face. Below that on the left is a drawing of the mosaic in a room over the stairs to the gallery, next to the right is another drawing of a Seraphim (this is a drawing of one of the great seraphim in the pendentives), finally to the far right is an image of Christ from the corner of a side-room of the South Gallery.

Below is a picture of a room off of the South Gallery that is closed to the public. That mosaic in the center of the apse is obviously the Christ in Saltzenberg's drawing on the right. The doorway to room was walled off until the Fossatis opened it. It was in total darkness. They opened up a window in the vault to let in light.

Next we are going to look at Cornelius's drawing of the North Gallery. It looks west, away from the altar.

Next we are going to look at Cornelius's drawing of the North Gallery. It looks west, away from the altar.

We can see that the closest vault to the altar has plain mosaic with no images. This is surprising because it was one of the holiest spots in the church. One can see that the plain field extends into the arches. Unlike the eastern half of South Gallery, which was closed to the public even in Ottoman times, this part was open all the time. I don't know how much the gallery was used in Ottoman times so I can speculate on the amazing survival of the mosaics being a result of them being closed off and inaccessible to the public. The second vault has a scene of the Baptism of Christ.

We can see that the closest vault to the altar has plain mosaic with no images. This is surprising because it was one of the holiest spots in the church. One can see that the plain field extends into the arches. Unlike the eastern half of South Gallery, which was closed to the public even in Ottoman times, this part was open all the time. I don't know how much the gallery was used in Ottoman times so I can speculate on the amazing survival of the mosaics being a result of them being closed off and inaccessible to the public. The second vault has a scene of the Baptism of Christ.

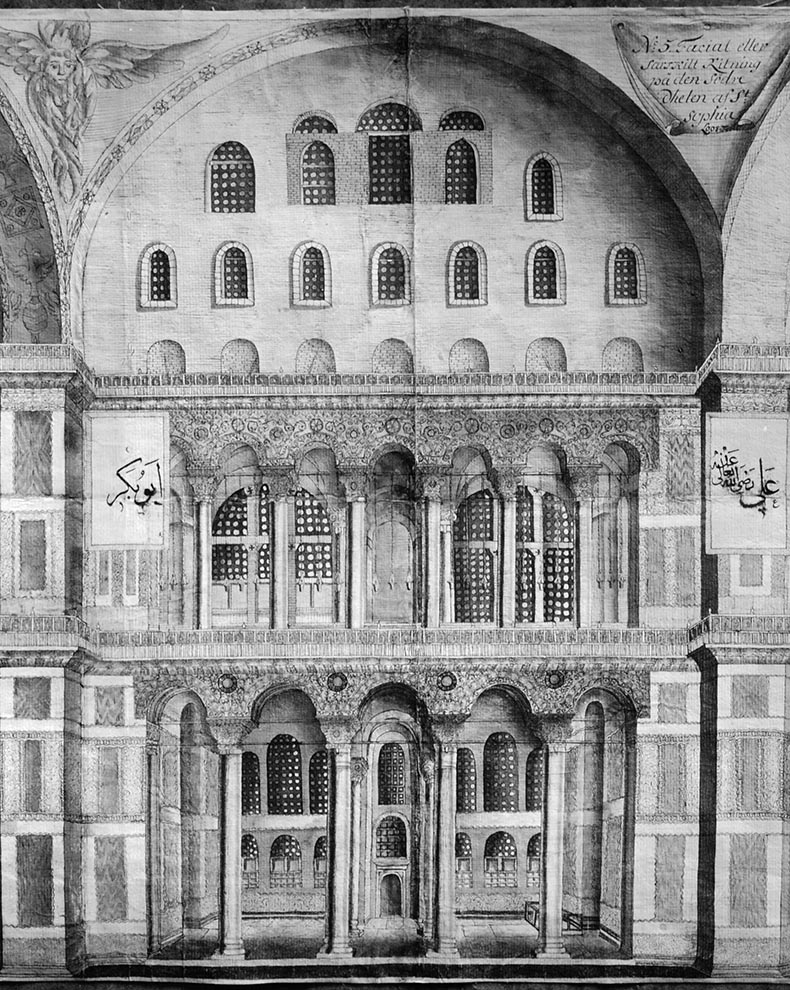

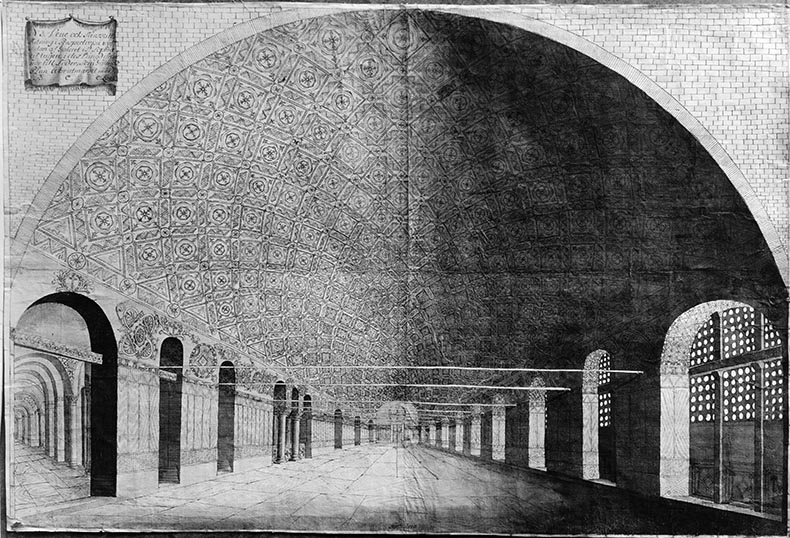

Below are two images of the West Gallery of Hagia Sophia. Cornelius did two drawings of it, the first one had a looser drawing of the pattern in the ceiling vault. Can you imagine how tedious drawing that pattern was? Not only did it have to be perfect he had to scale it down in perspective.

The floor is uncovered, so it was not used for Muslim worship at the time he drew it. I can't imagine they would have taken up the carpets just so he could draw the gallery. One can see the floor is marked up in the middle with replacement slabs.

Charles XII, Turkish Ambassador in Bender

Charles XII, Turkish Ambassador in Bender Ottoman Sultan Ahmet III

Ottoman Sultan Ahmet III Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia

Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints