The Empresses of Constantinople by Joseph McCabe

The Empresses of Constantinople by Joseph McCabe

In the year 1295 Michael, the eldest son of Andronicus II. and Anna, received the imperial title, and there ensued a remarkable competition of monarchs, great and little, for the honour of wedding a daughter to him. Charles of Sicily made an early offer of the hand of his daughter, but the legates returned disappointed to their master, and the smaller kings of the East sent in descriptions of the charms of their marriageable daughters. Amongst them was the King of Armenia, and the patriarch Alexis was deputed to go and examine the candidate. Alexis was captured by pirates as he crossed the sea, and, although the prelate made a skilful and vigorous escape, it was thought that Armenia was too remote and inaccessible. Legates were therefore sent to learn the terms of the King of Cyprus, and observe the merits of his daughter. When these also were unsuccessful, a stronger embassy was sent to Armenia, and the troop presently returned with two blushing candidates for the position of Empress.

The King of Armenia had, it seems, two marriageable daughters, and they were so equal in grace and beauty that no courtier could decide which was the more eligible. The Armenians insisted that both Ricta and Theophano should be conveyed to Constantinople, where noble husbands were still plentiful, and a message was sent to the capital to notify their coming. Andronicus gave them a princely welcome at the palace quay, and decided that the elder of the two should marry Michael. Their names were changed to Maria and Theodora, and, when the elder was united to the young Emperor, and received288 herself the imperial title, the younger was consoled by an alliance with the “Sebastocrator” John and a share of his sonorous title and more slender diadem. We do not know the age of Maria and are, as usual, without a description of her person; in fact, the quiet, unassuming ways of her very mediocre husband leave her in considerable obscurity for the first half of her life. We find her in 1306 setting out with him for the Bulgarian war and showing a fine spirit of patriotism. Andronicus had no money to pay the troops, and Maria, who remained in Adrianople, sold the jewels and melted the plate which had formed part of her dowry, in order to win success for her husband. They then returned to Constantinople to await, in exemplary patience, the natural transfer to them of the supreme power.

In 1318 their eldest son, Andronicus, was married to Irene, daughter of the Duke of Brunswick, and Michael and Maria went to Thessaly and engaged in the peaceful administration of that province. Two years later came a terrible message from Constantinople which put an end to the life of Michael and changed and saddened the whole course of Maria’s career. They had had two sons and two daughters. One daughter, Theodora, married the King of Bulgaria; the elder, Anna, married the Prince of Epirus, and, when he was assassinated, married his murderer. Tragedy seemed to dog the footsteps of the descendants of Michael Paleologus and Theodora, and a far more terrible experience was reserved for the sons, Andronicus and Manuel. Their father had consented to leave them at Court under the eye of the old Emperor, and that monarch’s idea of training them was unhappily consistent with a great deal of spoiling and pampering. Manuel, the younger brother, seems to have had a more sober and industrious character; the elder, Andronicus, was a vain, handsome and unscrupulous youth, whose light head was soon turned by the flattery of courtiers. His days were spent in hunting, his nights in the pleasures of the table, the dice-board, or the289 enervating chambers of courtesans. He was the natural heir to the throne, after his father, and already enjoyed the imperial title, so that parasites gathered thick about his person. He outran his ample income, and was forced to borrow large sums of money from the Genoese bankers of the suburb of Galata in order to maintain his luxuries and his mistresses.

The old Emperor did not fail to perceive the debasement of the character of his favourite grandson, and sharply to reprove him, but the young man sank more deeply into debt, and began at length to feel impatient of the long delay that must ensue before the keys of the imperial treasury would come into his hands. He contemplated a series of wild intrigues for the purpose of securing an immediate independence and control of at least a small dominion. At one moment he meditated seizing the throne of Armenia, on the pretext that it was his mother’s appanage; at other times he aspired to rule the island of Lesbos, the Peloponnesus, or any other fragment of the Empire from which he could wring the price of his pleasures.

The older Andronicus watched him vigilantly, and his intemperance soon led to a tragedy which definitely turned his grandfather against him. He was informed that a rival secretly visited the house of one of his mistresses, a lady of the Byzantine nobility and of very Byzantine laxness of morals, and he posted a band of archers and swordsmen near the house, with orders to fall upon any man who approached. It happened that on the same evening, about midnight, Manuel had occasion to see his elder brother at once, and expected to find him at the house of his mistress. He was not recognized by the assassins, and was murdered. This was the news which came to Michael and Maria in the autumn of 1320. Michael was in poor health at the time, and the shock ended his life. Maria seems to have taken the veil, as we generally find her named Xene in the chronicles after this date, but we290 shall find that she neither repudiated her elder son nor retired wholly from the world.

The older Andronicus watched him vigilantly, and his intemperance soon led to a tragedy which definitely turned his grandfather against him. He was informed that a rival secretly visited the house of one of his mistresses, a lady of the Byzantine nobility and of very Byzantine laxness of morals, and he posted a band of archers and swordsmen near the house, with orders to fall upon any man who approached. It happened that on the same evening, about midnight, Manuel had occasion to see his elder brother at once, and expected to find him at the house of his mistress. He was not recognized by the assassins, and was murdered. This was the news which came to Michael and Maria in the autumn of 1320. Michael was in poor health at the time, and the shock ended his life. Maria seems to have taken the veil, as we generally find her named Xene in the chronicles after this date, but we290 shall find that she neither repudiated her elder son nor retired wholly from the world.

The elder Andronicus now made it clear that his grandson should not inherit the purple, but he unfortunately committed a fresh blunder, which strengthened the hands of the young Emperor. The proper and most worthy—or least unworthy—heir to the throne was now the younger son of Anna of Hungary, Constantine, who had for some years been content with the lower title of “despot” and the government of Thessaly and Macedonia. He had, as we saw, married the daughter of the minister Muzalo. Finding a pretty maid among the common servants of his wife’s household, he had made her his mistress, and, as Muzalo’s daughter soon died, Cathara was raised to the rank of companion. They had a remarkably beautiful boy, who went by the name of Michael Cathara. After a time the roving eye of Constantine was arrested by the charm of the wife of one of his secretaries, and he proposed to bestow part of his affection on her. She pleaded the claims of her husband and the prescriptions of virtue; her husband promptly disappeared, as so many inconvenient husbands did in the Byzantine Empire; and the “new Hypatia,” as the chronicler calls her, shared the crown and the couch of the Despot of Thessaly. Her beauty, wit and culture are said to have placed her before all other women of her age, though there is a taint of sacrilege in the comparison with the virtuous, philosophical and venerable Hypatia of Alexandria. Cathara was dismissed, and Michael Cathara became a page at the Court of the elder Andronicus.

The Emperor, now a gouty and feeble old man of sixty-four, was again seduced by the superficial charm of a handsome boy, and treated Michael with a favour which clearly marked him for the ultimate possession of the throne. He gave the boy the imperial title, and kept him by his side when he received ambassadors. When the elder Michael died, and it was necessary, according291 to custom, to frame a new oath of allegiance to the Emperors, the name of the younger Andronicus was expressly excluded, and the officers swore only to obey the old Emperor and whomsoever he might associate with himself. This imprudent choice gave some of the discontented nobles a pretext to disregard their oaths, and they entered into secret alliance with the younger Andronicus. In order, however, to follow intelligibly the further fortunes of the imperial women, it will be necessary to give a brief account of this conspiracy and its leaders.

The most prominent figure among the discontented nobles was John Cantacuzenus, a very distinguished and cultivated noble, a later Emperor, and one of the chief historians of the period. The tortuousness of his career and the cloak of hypocrisy in which he foolishly imagines that he has concealed his ambition warn us to read his account of his times with discretion. His history opens with a deliberate concealment of the murder of Manuel and of the flagrant vices of his associate, Andronicus, and it remains mendacious and hypocritical to the last page. Such was the chief character who will mingle in the story of the Empresses for the next twenty years. He frowned on the low birth of Michael Cathara, was indifferent to the vices of Andronicus, and secretly cherished an ambition to occupy the throne. With him were Theodore Synadenus, a noble of equal distinction and more substantial character; Sir Janni (probably Sir John), an unscrupulous Choman adventurer; and Apocaucus, a successful financier, of low birth, who begged to be allowed to share the risk and profits of the speculation. Secret vows of fidelity were exchanged, and the more wealthy members of the group purchased the administration of distant provinces, in which they might raise and arm troops.

The most prominent figure among the discontented nobles was John Cantacuzenus, a very distinguished and cultivated noble, a later Emperor, and one of the chief historians of the period. The tortuousness of his career and the cloak of hypocrisy in which he foolishly imagines that he has concealed his ambition warn us to read his account of his times with discretion. His history opens with a deliberate concealment of the murder of Manuel and of the flagrant vices of his associate, Andronicus, and it remains mendacious and hypocritical to the last page. Such was the chief character who will mingle in the story of the Empresses for the next twenty years. He frowned on the low birth of Michael Cathara, was indifferent to the vices of Andronicus, and secretly cherished an ambition to occupy the throne. With him were Theodore Synadenus, a noble of equal distinction and more substantial character; Sir Janni (probably Sir John), an unscrupulous Choman adventurer; and Apocaucus, a successful financier, of low birth, who begged to be allowed to share the risk and profits of the speculation. Secret vows of fidelity were exchanged, and the more wealthy members of the group purchased the administration of distant provinces, in which they might raise and arm troops.

The old Emperor detected the conspiracy, and made an effort to check it. In the spring of 1321, on the292 morning of Passion Sunday, Andronicus was summoned to the palace of his grandfather and was forbidden to communicate with any person until he had seen the Emperor. The message was alarming, but the messenger was probably open to bribery, and the other conspirators were hastily warned. They decided to bring a troop of armed men into the hall of the palace, and, if the old Emperor were heard to speak angrily to his grandson in the inner chamber, rush in and despatch him. It will be noticed that the Byzantine Court was now but the shadow of its former greatness. The thousands of watchful Scholarians and Excubitors had long disappeared, even the stalwart and faithful English and Scandinavian Varangians could be hired no longer in any number, and a group of venal Cretan or Italian guards alone protected the approach to the throne. But the elder Andronicus, who had gathered the bishops in his chamber to hear him charge and convict his grandson, learned that a troop waited in the hall without, and the conference ended in hypocritical embraces and vows of mutual fidelity. The nobles, however, resented this solution. In their respective provinces, to which they were ordered, they raised their troops and concentrated at Adrianople. When Andronicus saw that they had a serious army he fled to join them, and they soon began to march over the provinces toward the capital.

Andronicus the elder was at first content to send a regiments of priests and monks into the streets of Constantinople with Bibles, making every citizen swear not to desert their lawful monarch. The oath was taken with the customary fluency, and the customary reserve; but the insurgents came nearer and nearer over the roads of Thrace, and a fresh peace had to be arranged. The grandson was now to have Thrace for his personal dominion, with Adrianople for capital, and the right of succession to the whole Empire. The young Empress Irene, who seems to have been little more than a spectator of the stormy seas into which her marriage had293 drawn her, joined her husband at Adrianople, presented him with a baby, and lived for a few months longer to witness his debauchery and infidelity. Before very long her reckless husband attempted to seduce the wife of one of his chief supporters, Sir Janni, and that commander, already jealous of the greater favour shown to Cantacuzenus, deserted to Constantinople and persuaded the elder Andronicus to try the fortune of war once more.

The Empress Maria, or the nun Xene, as she seems to have become, took the part of her son in the quarrel with the older Emperor. There is no evidence that she was a sincerely religious woman; indeed, the fact that she sided with her worthless son prevents us from supposing this. She probably trusted to return to Court in his train. She had remained in Thessalonica since the death of her husband, and she endeavoured to secure interest for her son in that province. The older Emperor, however, sent his son Constantine to Thessalonica, and Xene was arrested and shipped, in a very unceremonious fashion, to Constantinople. Constantine was now in a fair way to attain the Empire, and his “new Hypatia” must have enjoyed visions of a very speedy accession to power. But soon afterwards Constantine was captured by his nephew’s troops and committed to prison, from which he would never emerge. The unknown lady of such remarkable beauty and accomplishments, Constantine’s wife, now disappeared into the obscurity from which she had come, and Xene returned to hope.

The old Emperor was checked by the disaster of his son and sued for peace. He sent Xene to negotiate with him, and Andronicus and his friends were soon enjoying themselves once more in the capital. Irene had set out with him from Adrianople, but she died on the journey. Her life must have been unhappy, but the widower found consolation, and we find the earlier Irene’s daughter, Simonides, included in the list of the noble dames who consoled him. Simonides had entered the world encircled by a halo of miracle, but she was not294 destined to issue from it in a corresponding odour of sanctity. Few did in mediæval Byzantium. She had, as I said, returned from Servia after the death of the Kral, and was living in the city, a comfortable widow of thirty-three, when her handsome and profligate nephew came back to Court, more wealthy and luxurious than ever. There is no room for doubt that she entered into a liaison with Andronicus, since the old Emperor himself publicly referred to it as a notorious fact.

Xene had remained in Thrace, where, after a second marriage, which we will describe in the next chapter, Andronicus joined her. The town of Didymoteichus (now Demotica), about twenty miles to the south of Adrianople, became at this point the seat of a royal residence and a most important centre of intrigue in Byzantine history. From that town Xene and her son presently sent a most affectionate message to Xene’s daughter Theodora, who had married the King of Bulgaria, or two kings of Bulgaria in succession. The ladies of the Paleologi family were almost all remarkable for their adaptability to changes of domestic circumstances. It was twenty-three years since Xene had sent her daughter to Bulgaria, and she had not seen her since; Andronicus had never seen his sister. They now felt a sudden and most pressing desire to meet her, and she and King Michael came to spend a week at Didymoteichus. The real object was, of course, to arrange an alliance with Bulgaria, to counterbalance the older Emperor’s alliance, through Simonides, with Servia. Michael, a man of loose life and coarse and repulsive manners, was flattered by the liberal attentions of the imperial nun, and when Andronicus gave him a more substantial proof of their esteem, in the shape of a large promise of money and territory, he went home to mobilize his troops. In a short time the news reached Constantinople that the banners of civil war were to be raised once more. No one was surprised, as the year had opened with unmistakable portents. A muddy pig had295 scattered a procession of bishops, which accurately foreshadowed trouble in the Church; and there had been two eclipses of the moon in three months, than which there could be no surer foreboding of trouble in the State.

The senior Emperor had recourse at once to his futile diplomacy and his synods of bishops. He drew up a formidable indictment of his grandson, and submitted to the Empire that a man who had seduced his aunt, appropriated imperial funds, and committed many other grave crimes, was unfit to wear the purple. In his history of the time Cantacuzenus laboriously meets this indictment, but his answers are feeble and evasive, and, since he prudently overlooks the charge of a liaison with Simonides, we have little hope of relieving her character of that imputation. It does not seem to have made any difference to Xene’s loyalty to her son, and we must conclude that she was bent on returning with him to the Court. However, after some months of mutual incrimination, the troops were set in motion, Constantinople was taken (23rd May 1328), and the long and lively reign of Andronicus II. came to a close. Few tears were shed, or ever will be shed, over the fall of that selfish and incompetent ruler. He was granted a generous income, and he continued to live, in complete privacy, for four years.

Xene remained at Didymoteichus, which had now become an important centre of the shrunken Empire. The success of her son brought her to realize that he was surrounded by men and women who were bitterly hostile to her, and she no doubt felt it more prudent or agreeable to enjoy the tranquillity of the provincial palace. This tranquillity was rudely disturbed two years later, when Andronicus fell seriously ill at Didymoteichus, and the members of the Cantacuzenus family and faction betrayed their ambition.

The picture of the scene which we have in the pages of Cantacuzenus himself is just as affecting, and just as mendacious, as Anna Comnena’s picture of the scene296 at her father’s death. The dying Andronicus—it was, at all events, believed by all that he was dying—summoned his wife and friends to his couch, and, putting the right hand of the Empress in the right hand of his faithful Cantacuzenus, entrusts to him her safety and that of the Empire. When the mother of Cantacuzenus (a quaint type of nun whose acquaintance we shall make presently) asks him his wishes in regard to his mother, he feebly murmurs that “there cannot be two rulers.” Cantacuzenus weeps so copiously that he must retire to wash his face, in order to hide his grief from his beloved friend. Courtiers press him to seize the purple, and he refuses. They urge him to put to death, or put out the eyes of, the despot Constantine, Andronicus’s uncle, who still lingers in his prison. Again Cantacuzenus shrinks from the suggestion, and, in order to protect Constantine from their murderous designs, he hides him in an underground chamber.

One feels that the whole story is a masterpiece of lying, and it is not difficult to learn the truth. Round the bed of the unconscious Andronicus Cantacuzenus and his mother and friends pursued a desperate intrigue for power. Anna was young and helpless, and might be used for furthering their plan. Xene, however, watched their intrigue with furious anger and fear, and pitted her hatred against that of the mother of Cantacuzenus. Constantine was thrust in a loathsome and secret dungeon by Cantacuzenus, lest any faction should remember that he was the real heir to the throne. Even the old ex-Emperor at Constantinople was approached, and was offered the alternative of death, exile or the monk’s tonsure. With many tears he embraced the least painful of the three proposals and adopted the name of Antony. The triumph of Cantacuzenus seemed to be assured when, to their astonishment and mortification, Andronicus emerged from his stupor and returned to health.

Xene at once appealed to her son to punish the intriguers, but he was either deceived by the hypocritical professions of Cantacuzenus or not strong enough to face his hostility. Xene now felt that she had incurred their mortal vindictiveness and retired to Thessalonica. There she induced the citizens to swear that they would protect her, and she even adopted as her son the wily and accommodating Sir Janni, who governed the province. Sir Janni had not long to wait for his reward—the fortune of his “mother.” She died four years later (1334), and was buried at Thessalonica, having run a strange course since she had nervously quitted her Armenian home thirty-eight years before.

The older Andronicus had died two years before, at the age of seventy-two. Nicephorus Gregoras, our best authority for the time, tells us how he spent a night in pleasant conversation with the old man in February 1332. Andronicus, or Antony, died the next day, and was buried in his monkish robe. The same passage of Gregoras gives us our penultimate reference to the interesting Simonides. She was present at the conversation, and we seem to be justified in inferring that she “kept house” for her father. The last glimpse we have of her is a fitting crown to her strange career. We faintly discern her, some years later, as a royal nun in the Court of her nephew and former lover.

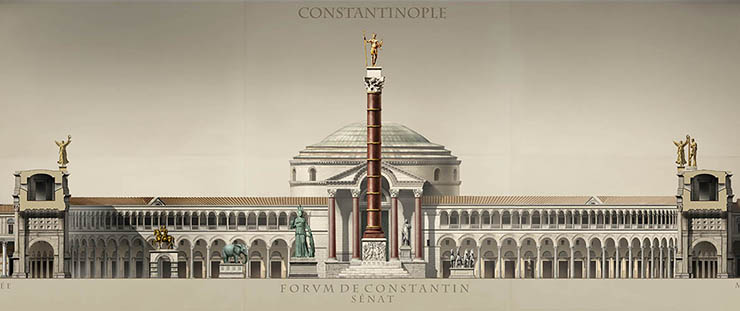

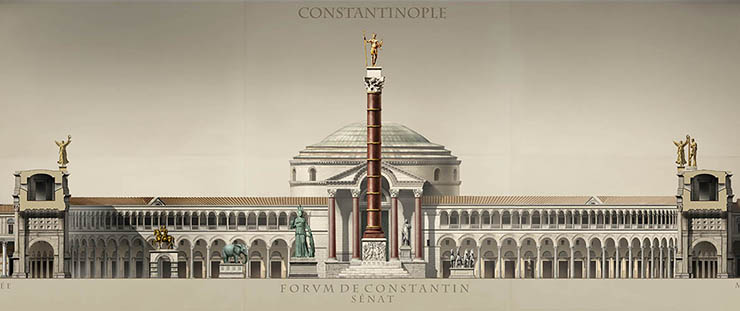

The last chariot race in Constantinople was in the huge courtyard of the Blachernae palaces for the wedding of a prince of the Angelid Dynasty in 1200. The wedding cost a fortune and the people had to pay a special tax to cover the cost.

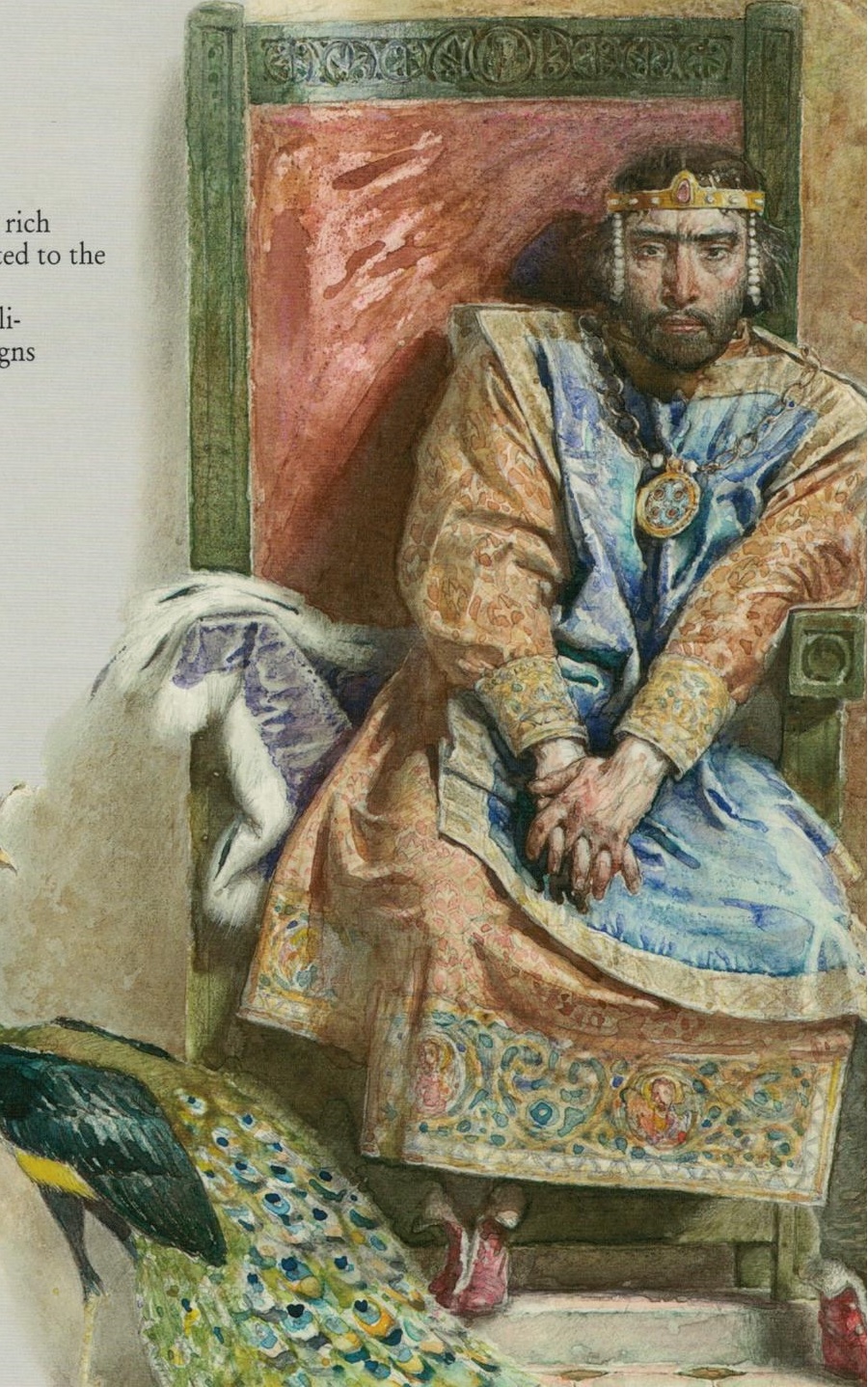

The last chariot race in Constantinople was in the huge courtyard of the Blachernae palaces for the wedding of a prince of the Angelid Dynasty in 1200. The wedding cost a fortune and the people had to pay a special tax to cover the cost. Emperor John I Tzimiskes, the murderer of his uncle Nikephorus II Phocas in his bed in the Boukoleon Palace. John married his uncle's wife, who was his co-conspirator in the assassination.

Emperor John I Tzimiskes, the murderer of his uncle Nikephorus II Phocas in his bed in the Boukoleon Palace. John married his uncle's wife, who was his co-conspirator in the assassination.

The Empresses of Constantinople by Joseph McCabe

The Empresses of Constantinople by Joseph McCabe The older Andronicus watched him vigilantly, and his intemperance soon led to a tragedy which definitely turned his grandfather against him. He was informed that a rival secretly visited the house of one of his mistresses, a lady of the Byzantine nobility and of very Byzantine laxness of morals, and he posted a band of archers and swordsmen near the house, with orders to fall upon any man who approached. It happened that on the same evening, about midnight, Manuel had occasion to see his elder brother at once, and expected to find him at the house of his mistress. He was not recognized by the assassins, and was murdered. This was the news which came to Michael and Maria in the autumn of 1320. Michael was in poor health at the time, and the shock ended his life. Maria seems to have taken the veil, as we generally find her named Xene in the chronicles after this date, but we

The older Andronicus watched him vigilantly, and his intemperance soon led to a tragedy which definitely turned his grandfather against him. He was informed that a rival secretly visited the house of one of his mistresses, a lady of the Byzantine nobility and of very Byzantine laxness of morals, and he posted a band of archers and swordsmen near the house, with orders to fall upon any man who approached. It happened that on the same evening, about midnight, Manuel had occasion to see his elder brother at once, and expected to find him at the house of his mistress. He was not recognized by the assassins, and was murdered. This was the news which came to Michael and Maria in the autumn of 1320. Michael was in poor health at the time, and the shock ended his life. Maria seems to have taken the veil, as we generally find her named Xene in the chronicles after this date, but we The most prominent figure among the discontented nobles was John Cantacuzenus, a very distinguished and cultivated noble, a later Emperor, and one of the chief historians of the period. The tortuousness of his career and the cloak of hypocrisy in which he foolishly imagines that he has concealed his ambition warn us to read his account of his times with discretion. His history opens with a deliberate concealment of the murder of Manuel and of the flagrant vices of his associate, Andronicus, and it remains mendacious and hypocritical to the last page. Such was the chief character who will mingle in the story of the Empresses for the next twenty years. He frowned on the low birth of Michael Cathara, was indifferent to the vices of Andronicus, and secretly cherished an ambition to occupy the throne. With him were Theodore Synadenus, a noble of equal distinction and more substantial character; Sir Janni (probably Sir John), an unscrupulous Choman adventurer; and Apocaucus, a successful financier, of low birth, who begged to be allowed to share the risk and profits of the speculation. Secret vows of fidelity were exchanged, and the more wealthy members of the group purchased the administration of distant provinces, in which they might raise and arm troops.

The most prominent figure among the discontented nobles was John Cantacuzenus, a very distinguished and cultivated noble, a later Emperor, and one of the chief historians of the period. The tortuousness of his career and the cloak of hypocrisy in which he foolishly imagines that he has concealed his ambition warn us to read his account of his times with discretion. His history opens with a deliberate concealment of the murder of Manuel and of the flagrant vices of his associate, Andronicus, and it remains mendacious and hypocritical to the last page. Such was the chief character who will mingle in the story of the Empresses for the next twenty years. He frowned on the low birth of Michael Cathara, was indifferent to the vices of Andronicus, and secretly cherished an ambition to occupy the throne. With him were Theodore Synadenus, a noble of equal distinction and more substantial character; Sir Janni (probably Sir John), an unscrupulous Choman adventurer; and Apocaucus, a successful financier, of low birth, who begged to be allowed to share the risk and profits of the speculation. Secret vows of fidelity were exchanged, and the more wealthy members of the group purchased the administration of distant provinces, in which they might raise and arm troops.