On cannot understate how Hagia Sophia was built and decorated to maximize natural and artificial light. Light was important not only from a practical purpose but also from a symbolic and spiritual basis. For Christians Christ is Divine Light incarnate. He himself said, "I am the light of the world: he who follows me... shall have the light of life" (john 8:12). In Hagia Sophia light is associated with the presence of God in the the liturgy and prayers performed there. Like the Temple in Jerusalem, upon which Hagia Sophia was planned, built and decorated, the church contains the uncontainable, God Himself as made manifest in Christ. Light, Christ and salvation are intertwined. The church of Hagia Sophia - the Holy Wisdom of God - was dedicated to Christ. Beyond the building and the splendor of its furnishings, the brilliance of the illumination within Hagia Sophia was an end in and of itself.

Above is a picture of the Great and Holy Vatopedi Monastery Katholikon Church on Mount Athos which was dedicated to the Nativity of the Virgin. The church dates from the 10th century. This view of the church at dusk and lit by candlelight gives us an idea of what Hagia Sophia would have looked like. Please take a look at the tripod silver candlestands, the one on the far right has an extension on it. This church also has a beautiful example of a 12th century Byzantine opus sectile floor, like the one at the Studion.

Above is a picture of the Great and Holy Vatopedi Monastery Katholikon Church on Mount Athos which was dedicated to the Nativity of the Virgin. The church dates from the 10th century. This view of the church at dusk and lit by candlelight gives us an idea of what Hagia Sophia would have looked like. Please take a look at the tripod silver candlestands, the one on the far right has an extension on it. This church also has a beautiful example of a 12th century Byzantine opus sectile floor, like the one at the Studion.

The church of Hagia Sophia was a essentially a stage on which to perform the liturgy and other ceremonies associated with the Imperial court and civic events. The church was carefully planned to align in the direction of sunrise at the winter solstice when light pours into the nave at the time of the church service, pointing at and then passing through the Royal Doors. Services and events were planned in various parts of the church when the light was best. This would change with the seasons and the corresponding position of the sun. You could even plan a service where the light would strike the altar, the ambo or certain icons down to the minute. One can still stand in Hagia Sophia and follow beams of sunlight as they move around the floor, cross the Ottoman additions like the Sultan's Box, and then move up the nave walls.

Above is an image of the 13th century Serbian Decani Monastery in Kosovo - Metohija, lit by candlelight. In the center is a great round chandelier hanging from the dome cornice, which mimics the great circle of light in Hagia Sophia. Each grouping has 8 candles.

Above is an image of the 13th century Serbian Decani Monastery in Kosovo - Metohija, lit by candlelight. In the center is a great round chandelier hanging from the dome cornice, which mimics the great circle of light in Hagia Sophia. Each grouping has 8 candles.

The oil lamps used in Hagia Sophia were either single glass or multiple glass polykandelon chandeliers that used floating-wicks. The wick is suspended in the oil by means of a metal bar and was made of twisted linen or cotton. Some lamps were made completely of glass with looped handles, usually three for suspension chains. Other glass lamps had metal rings around a collar. Suspension chains were attached to these metal collars. This is what is commonly called a mosque lamp today.

The metal used in the oil lamps was made of silver, silver-gilt or brass. Some lamps in very special locations might have been solid gold. The Emperor Manuel I Comnenus made a gift of a huge gold icon lamp set with a glass cup to hang above the Tomb of Christ in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. It cost 20 talents of gold and had been made for his father John II who died before it could be presented. The lamp carried the inscription "the purple-blooming child, Manuel, the emperor, hangs this on you, oh life-bringing tomb!" and was kept perpetually burning with scented oil. Manuel was buried in the Pantokrator monastery that was founded by his father and mother. Near his tomb was installed a slab believed to have been the stone that Christ's body lay upon after His death; it was said to spotted with tears of His Mother. Manuel had carried this slab on his own back in procession when it arrived in Constantinople. He had a similar gold icon lamp installed here in the Imperial mausoleum of the Comnenian dynasty to hang above the slab. There were a number of places in Hagia Sophia were a solid-gold lamp might have been hung. Most of the year the relics of the Passion were kept sealed up in their jeweled golden cases. One a year they were brought to Hagia Sophia for pilgrims to venerate them. You could view them from Wednesday evening to Friday at noon during Holy Week. Vast numbers of people visited Hagia Sophia during this period to see and venerate them, coming as far away as Northern Russia. The Passion relics were considered the most important and valuable of relics in the City by far. After 1204 the Crusaders sold most of them to King Louis IX of France who built Sainte-Chapelle to house them. Another location would have been over the altar, where there could have been several gold lamps hanging.

All of the lamps in Hagia Sophia were silver or silver gilt, even up until 1453. They didn't require that much silver to make - they were relatively light-weight because they were cut from sheet silver and had many piercings in them. They usually had open work bottoms with glass inserts, which were an innovation from the fourth century. The lamps were often cast in unusual shapes, taking the form of things like ships, dolphins, peacocks, crowns, and most often, crosses. Sometimes the inserts were made not of glass but carved in rock crystal. Many of them would have carried inscriptions that either commemorated the donor, were bible verses or spiritual messages. Silver polykandelon would have also carried stamped hallmarks showing their weight, the reign in which they were made and purity of the silver.

Above, two Byzantine polykandela in brass or bronze. The top one has four lamps, the bottom has 10. Polykandela in Hagia Sophia were made of silver and silver gilt.

Above, two Byzantine polykandela in brass or bronze. The top one has four lamps, the bottom has 10. Polykandela in Hagia Sophia were made of silver and silver gilt.

The 6th century, cross-shaped polykandelon shown above is made of silver and was produced in Constantinople at the same time Justinian's Hagia Sophia was built. It weighs 7 lbs and is the same size as Hagia Sophia's and came from the so-called Zion Treasure.

The 6th century, cross-shaped polykandelon shown above is made of silver and was produced in Constantinople at the same time Justinian's Hagia Sophia was built. It weighs 7 lbs and is the same size as Hagia Sophia's and came from the so-called Zion Treasure.

Oil lamps were hung from the dome, vaults, between columns from wall brackets. Brackets could be shaped to carry dolphins, dove and even human hands. Many of these are still in place in Hagia Sophia, today.

Great polykandelon were suspended from the dome cornice (80) and inside the dome itself (60) on long chains suspended just above the heads of the faithful, from a 6th century historian we read:

"No words are sufficient to describe the illumination in the evening: you might say that some nocturnal sun filled the majestic temple with light. From the deep wisdom of our Emperors has stretched from the projecting stone cornice, on whose back is plated the foot of the temple's lofty dome, long twisted chains of beaten brass... And to each chain are attached silver disks, suspended circle-wise in the air round the central confines of the church. Thus, descending from their lofty course, they float in a circle above the heads of men. The cunning craftsman has pierced the disks all over with his iron tool so that they may receive shafts of fire-wrought glass, and provide pendant sources of light for men at night. Yet not from disks alone does the light shine at night, for same circle you will see, next to the disks, the shape of the lofty cross with many eyes upon it, and in its pieced back it holds luminous vessels. Thus hangs the circling choir of bright lights. You might say you were gazing on the effulgent stars of the heavenly Corona close to Arcturus and the head of Draco."

The original iron brackets - 80 in all - can still be seen attached to the cornice of the dome. They date from the 6th, 10th and 14 centuries in slightly different forms, which corresponds to the dates of repairs to the dome. Russian travelers tell us that there were 80 6-8 light silver polykandelon hanging from the dome cornice, so those numbers match up exactly. The lamps hanging from the inside of the dome were in three smaller, concentric circles. Each polykandelon would have been around two feet wide and was either circular or cross-shaped. Each one would have contained around 10 lbs of silver that would cost $1,750.00 each for the silver today. 80 of them would cost $140,000.00. These lamps, which hung on 164 ft gilded iron chains, would have been serviced from the floor of the church. Fragments of the chains still survive.

Above the railing surrounding the dome cornice were single glass lamps hung from brackets. On special occasions choirs were placed here in the dome to chant and sing.

Around the nave there were 100 lights suspended from the gallery cornice alone. The brass bars they hung from are still in place, about 6 ft apart. Historical accounts tell us the lamps were hung at different lengths to create waves of light around the church. There were several hundred lights hung between the gallery columns on the second floor. All of these chains would have created a forest of hanging lines that would have vanished into the darkness at night. All in all there would have been several thousand lamps that would have illuminated Hagia Sophia at night, which would have shimmered softly like stars in the night sky.

The aisles of Hagia Sophia had their own set of glass lamps that hung over the most important icons there. These lamps were kept constantly burning, even during the day. There were probably several hundred of these.

There was one celebrated great glass lamp that was shown to pilgrims. It was said this lamp had fallen to the floor from a great height, but was not broken and kept burning. It was believed that some great force had gently lowered it to the marble pavement. This story reminds us of the danger of so many lamps hanging in Hagia Sophia that could potentially fall or have their glass lamps shatter spontaneously while burning. They added salt to the oil in the lamps to prevent spattering.

Oil lamps were an expensive way to light churches which provided weak light. Olive oil was the most commonly used because it produced the brightest light. It has been estimated that the 12-light chandelier in Hagia Sophia would only emit around 40 watts of illumination. They were expensive to maintain as well. They needed to be refilled and cleaned daily or weekly; replacement glasses were constantly needed to replace broken ones. Hagia Sophia had to allocate the cost of lighting to its annual budget. The Great Church had the income from 1100 commercial shops in Constantinople to support it. Emperors would also donate funds to Hagia Sophia to cover the cost of lamp oil to expand the frequency of night services in the church.

Sometimes the chandeliers in Hagia Sophia were put into motion - swaying from side to side - making the lights dance. This is still done in the monasteries on Mount Athos today. It's an amazing spectacle to see.

Hanging glass oil lamps were used in homes and in Imperial palaces, where scented oil was usually used. Usually a cheaper grade of olive oil was used in lamps and candelabra. Adding scent masked its odor. Spikenard, a Valerian plant scent from India was often added to the oil in lamps in churches, especially in the early days of Byzantium. Rose scent was much cheaper and commonly available. Monasteries and private homes could make rose scented lamp oil themselves. Scented rose oil was used on special occasions in Hagia Sophia, the altar of Hagia Sophia was regularly washed with rose water. Rose oil was used in vigil lamps that illuminated the famous icon of the Hodegetria Mother of God in her shrine near the Great Palace.

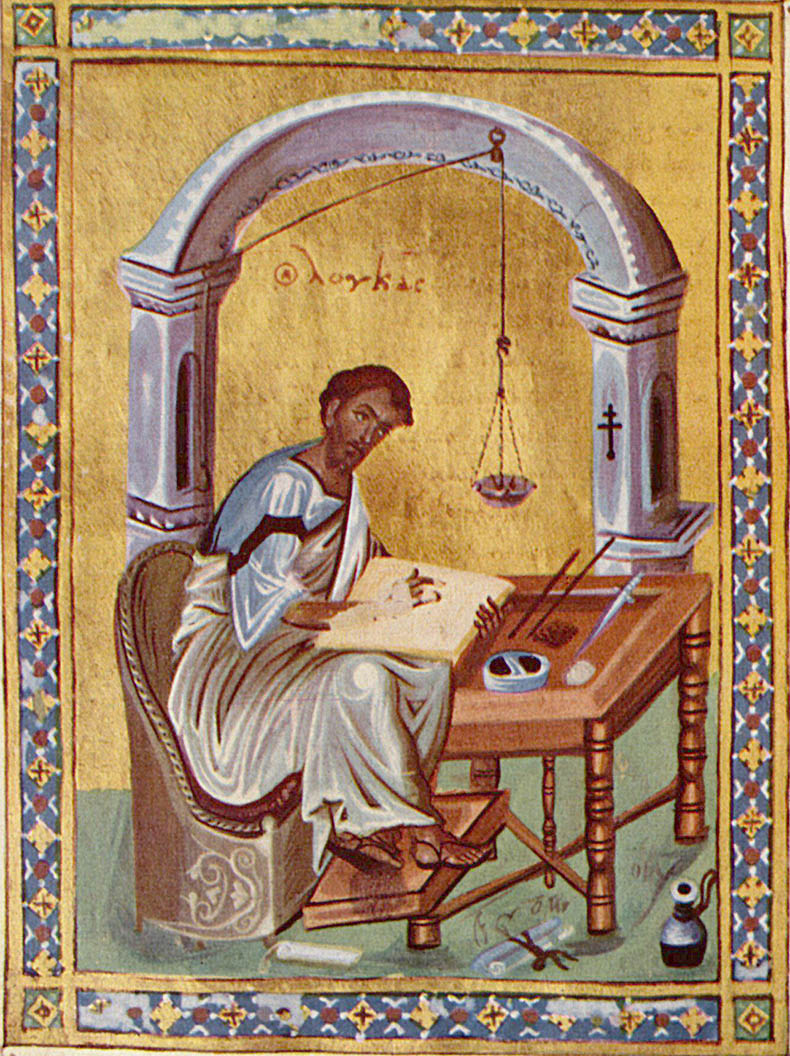

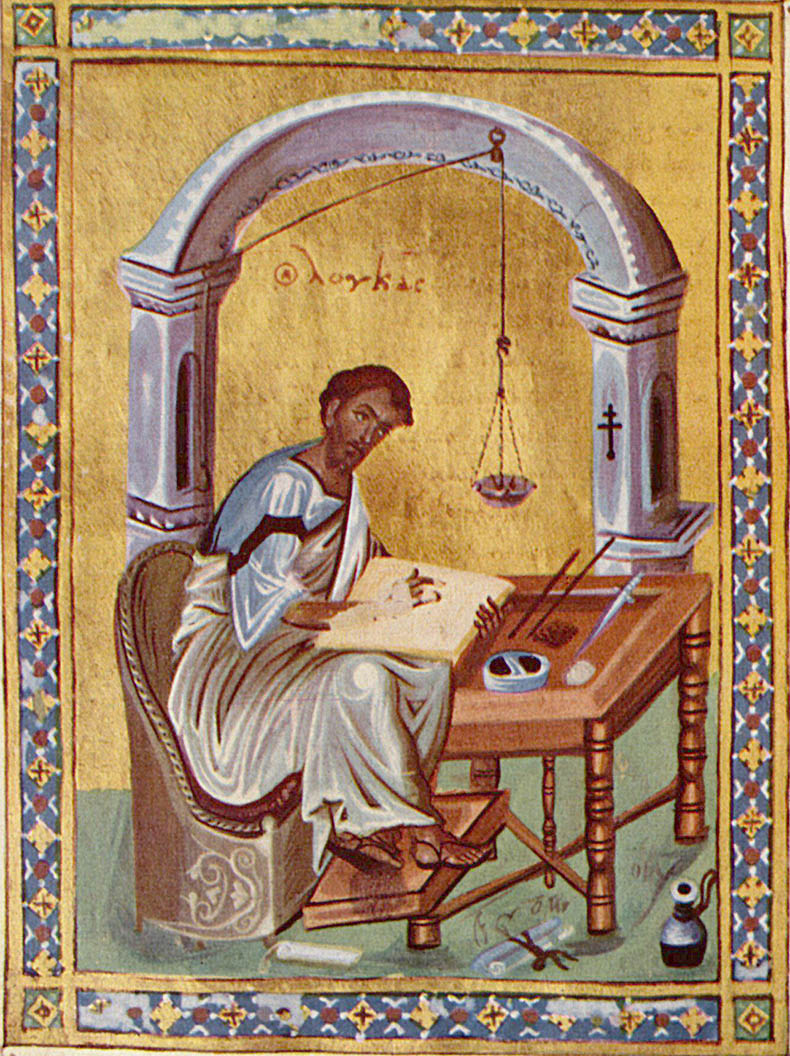

Above is an illustration of St. Luke at work compsong his Gospel. He is working using a glass oil lamp on an adjustable cord.

Above is an illustration of St. Luke at work compsong his Gospel. He is working using a glass oil lamp on an adjustable cord.

The oil from lamps that burned in front of certain hold icons was believed to have healing properties. There was a celebrated icon of the Archangel Michael "tou Eusebiou" in Constantinople that drew pilgrims for this very reason. It was believed that wrapping your head in the cord that held the lamp above an icon of Saint Stephen in Hagia Sophia could cure headaches. Russian pilgrims in Hagia Sophia were especially interested in an icon our their own Saints Boris and Gleb. It's an interesting fact that artists were waiting there to offer copies for sale.

After the 6th century and the loss of North African olive oil, there was a move to candles because the cost of burning oil lamps went up so much.

Lighting also came from candlestands, which followed Roman models. These could be single light or have multiple branches on them, they could be adjustable to raise and lower the lights. They could be placed in front of icons or used to read from lecterns, or light paths, stairways or corridors.

Candlestands were generally made as three-legged tripods and you can still see the places were they stood on the floor of Hagia Sophia. The marble floor in front of the Deesis still has the marks of it's candlestand. There were huge, elaborate 10 ft tall tree-shaped candlestands in silver-gilt on the stylobate around the altar of Hagia Sophia, on the ambo and two more along the parapet of the west gallery (their iron Ottoman replacements are there now). Each one of these would have contained around 300 lbs of solid silver - or $53,000 each. Justinian gave Hagia Sophia two rock crystal candelabra with feet of gold.

The advantage of candlestands is that they can be moved around where you want them to be. The danger is that - unless they are securely built - they could be turned over and cause fires.

Candles were used in huge numbers for processions in Hagia Sophia, of which there were dozens during the say. During everyday liturgy common people, as well as aristocrats, would be expected to hold candles, which would be left behind afterwards as votive lights. Pilgrims bought vast numbers of them during their visits to Hagia Sophia to place in front of relics and sacred icons. Russian pilgrims considered Hagia Sophia to be so sacred that they venerated the building itself and lit candles to it. After they left the unburned parts of their candles were recycled into new ones. Just like today pilgrims would have taken "sanctified" candles home as souvenirs. There were problems with people who swindled pilgrims who bought candles. Pilgrims were encouraged to buy big expensive candles, which were switched with smaller ones after they left. The big candles were then melted down and sold as raw wax.

There were professional tour guides who worked inside Hagia Sophia who could help you see all of the famous and sacred things that had been placed there over the centuries. they could get you access to many of the things that were off-limits to the general public. These guides spoke multiple languages and knew all the stories about Hagia Sophia, trues ones as well as the mythical fables. They knew what interested different nationalities and would take you to the things that were connected to them, like national saints or things that had been paid for by your prince. They could introduce you to the clergy of the cathedral and admittance to special services. These guides could also take you around to the other sites of the City. When pilgrims returned home they would recommend these guides to others. They were considered essential to the success of your pilgrimage.

There were professional tour guides who worked inside Hagia Sophia who could help you see all of the famous and sacred things that had been placed there over the centuries. they could get you access to many of the things that were off-limits to the general public. These guides spoke multiple languages and knew all the stories about Hagia Sophia, trues ones as well as the mythical fables. They knew what interested different nationalities and would take you to the things that were connected to them, like national saints or things that had been paid for by your prince. They could introduce you to the clergy of the cathedral and admittance to special services. These guides could also take you around to the other sites of the City. When pilgrims returned home they would recommend these guides to others. They were considered essential to the success of your pilgrimage.

The production and sale of candles in Constantinople was strictly controlled. Bad quality tallow candles of animal fat were dangerous, smelled bad and were banned in retail sales. Hagia Sophia ran its own candle production and retail sales through its own shops. While the primary objective of their candle making was to satisfy the needs of Hagia Sophia and its clergy, candles would have been big potential source of income for the cathedral through sales in the church itself to worshipers and pilgrims.

Wax and candle merchants were called Keropoioi. Candle makers were required to work out of shops and not sell their goods in the street or market. They often sold their wares by weight and with separate holders; broken candles might also be brought to them for repair. Not wanting to have to buy them from merchants, being sufficient in candles was the goal of every church which they produced for their own use. If the church didn't have their own beehives there were tens of thousands of them in around Constantinople that supplied both honey and wax. Many of these that were on lands that were connected to the great monasteries and convents of Constantinople in commercial activities. We know of one wax and honey producer, a 9th century saint named Philoretos, who owned and operated 250 hives in the Pontos on the Black Sea. Honey and wax was also imported from Bulgaria and Russia. Byzantine beehives that have survived were made of fired clay in cone-shaped cylinders. They also were also made in wood, which we know from manuscript illustrations. No examples have survived.

Constantinople had public street lighting using oil lamps. These oil lamps were polycandela made of brass with glass inserts. The owners of shops and workshops were required to provide lighting in the arcades in front of their places of business. Up until 1204 many of Constantinople's streets were columned porticos. In the 12th century there were around 6,000 shops in the city. Private homes used lots of oil lamps, houses had few windows, and they were absolutely essential for day-to-day life. They were made of glazed ceramic or brass. Thousands of these have survived and can be bought for almost nothing online.

For more consult "Lighting in Early Byzantium" by Laskarina Bouras and Maria G, Parani, a publication of Dumbarton Oaks.

For more consult "Lighting in Early Byzantium" by Laskarina Bouras and Maria G, Parani, a publication of Dumbarton Oaks.

There were professional tour guides who worked inside Hagia Sophia who could help you see all of the famous and sacred things that had been placed there over the centuries. they could get you access to many of the things that were off-limits to the general public. These guides spoke multiple languages and knew all the stories about Hagia Sophia, trues ones as well as the mythical fables. They knew what interested different nationalities and would take you to the things that were connected to them, like national saints or things that had been paid for by your prince. They could introduce you to the clergy of the cathedral and admittance to special services. These guides could also take you around to the other sites of the City. When pilgrims returned home they would recommend these guides to others. They were considered essential to the success of your pilgrimage.

There were professional tour guides who worked inside Hagia Sophia who could help you see all of the famous and sacred things that had been placed there over the centuries. they could get you access to many of the things that were off-limits to the general public. These guides spoke multiple languages and knew all the stories about Hagia Sophia, trues ones as well as the mythical fables. They knew what interested different nationalities and would take you to the things that were connected to them, like national saints or things that had been paid for by your prince. They could introduce you to the clergy of the cathedral and admittance to special services. These guides could also take you around to the other sites of the City. When pilgrims returned home they would recommend these guides to others. They were considered essential to the success of your pilgrimage. For more consult

For more consult

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints