From O City of Byzantium by Niketas Choniates

Emperor Isaakios anchored the succession of his family on the three children begotten of his former marriages: two females and one male. He tonsured the older daughter a nun and at great expense converted the so-called house of Ioannitzes into a nunnery (Empress Xene wanted very much to do this after the death of her husband, Emperor Manuel) to cloister her within, setting her apart and consecrating her as a ewe lamb. His second daughter he sent to wed the son of Tancred [1193], the king of Sicily, who had succeeded William after his death; the latter, as we have related, was he who waged war against the Romans on both land and sea. He educated his son Alexios as heir to the throne, although he never imagined that his own life would come to an end so soon, nor did he suspect his own fall from power, forecasting without doubt that he would reign for thirty-two years as though he could forsee the divine will or that he himself could stake out the limits of life which God had put in his own power.

Emperor Isaakios anchored the succession of his family on the three children begotten of his former marriages: two females and one male. He tonsured the older daughter a nun and at great expense converted the so-called house of Ioannitzes into a nunnery (Empress Xene wanted very much to do this after the death of her husband, Emperor Manuel) to cloister her within, setting her apart and consecrating her as a ewe lamb. His second daughter he sent to wed the son of Tancred [1193], the king of Sicily, who had succeeded William after his death; the latter, as we have related, was he who waged war against the Romans on both land and sea. He educated his son Alexios as heir to the throne, although he never imagined that his own life would come to an end so soon, nor did he suspect his own fall from power, forecasting without doubt that he would reign for thirty-two years as though he could forsee the divine will or that he himself could stake out the limits of life which God had put in his own power.

It was not only Alexios Branas and Theodore [Mangaphas] the Lydian who lifted their heels against this emperor; but many others also conferred upon themselves the title of emperor. For example, a certain Alexios, who claimed to be the son of Manuel, emperor of the Romans, so excellently played his role in the drama and so brilliantly donned the mask of Emperor Alexios that he dyed his hair the same yellowish brown color and even affected the young emperor's stammer. The lad set out from Constantinople and was first seen in the cities along the Maeander [1189]. He took up quarters in a small town called Harmala, and there he was entertained as the guest of a certain Latin to whom he announced his identity (he said, in accordance with our brief account above, that when he was delivered over by Andronikos to be cast into the deep of the sea, the men who were commanded to carry out this deed took compassion on him because they had sworn allegiance to his father). Together they traveled to Ikonion, where the old sultan (his son Qutb al-Din had not yet removed him from power) looked upon him as the true son of Emperor Manuel and never addressed him or dealt with him as an outsider and an impostor. He would often rebuke the sultan; reminding him of the benefactions his alleged father Manuel had bestowed upon him, he called him an ingrate and reproached him for lack of human feeling should he not be moved to come to the aid of the unfortunate child of his friend.

Moved to honor him both by his shamelessness and his resemblance [to his so-called father], the sultan gratified him with many gifts and gladdened him with great expectations. Once, when a Roman envoy in attendance listened to the young man exalting the eminence of his noble birth, the sultan asked whether he knew him to be Emperor Manuel's son. When he answered nothing more than that this son had truly perished and in vain did the lad Alexios fabricate such falsehoods, surfacing with the name of one seen lying dead in a watery grave, the youth, who boiled with rage and was hot with wrath, would have seized the envoy by the beard had not the latter, provoked to anger, stalwartly repulsed the false-Alexios. The sultan then admonished them for behaving ill and commanded them to remain calm.

Giving in to the youth's persistent entreaties, the Turkish ruler did not even then limit his excessive demands, but issuing a special letter of the sultan which the Turks called mansur, he allowed him to enlist with impunity as many of his subjects as he could. Alexios departed, and when he showed the letter to the Turks, he attracted the amir Arsan and many others who habitually plundered the Roman provinces. Within a short time, eight thousand troopsTM62 chose to follow him to war against the cities along the Maeander. Some capitulated without a fight, while those that resisted were completely destroyed. He even laid waste the planted fields and, as a result, was called Crop-burner.

Giving in to the youth's persistent entreaties, the Turkish ruler did not even then limit his excessive demands, but issuing a special letter of the sultan which the Turks called mansur, he allowed him to enlist with impunity as many of his subjects as he could. Alexios departed, and when he showed the letter to the Turks, he attracted the amir Arsan and many others who habitually plundered the Roman provinces. Within a short time, eight thousand troopsTM62 chose to follow him to war against the cities along the Maeander. Some capitulated without a fight, while those that resisted were completely destroyed. He even laid waste the planted fields and, as a result, was called Crop-burner.

Many and more were sent to wage war against the lad, but they were unable to perform any dashing feat and returned without accomplishing anything, afraid lest they be betrayed by their Roman comrades, espe- cially those who inclined towards the one who called himself the emperor's son and preferred him to the reigning Emperor, Isaakios. He was hailed by the common masses and the rural populace, adored, it seems, by word and name and on sight. Those who frequented the imperial court and knew for a certainty that the Emperor Manuel's son Alexios had long ago departed this life marveled at these developments; they knew the facts but indulged in speculations to their own pleasure.

Among others, the emperor's brother Alexios, who reigned later, led an expedition. He did not engage Alexios in a single battle but encamped apart and at a distance in defense of the remaining territories that had not gone over to Alexios and checked the flow of defectors who would pass over to the resurrected Alexios. As the issue thus hung in doubt, and Alexios gained ground and waxed strong while the sebastokrator cowered and shunned face-to-face conflict, God, in a novel manner, terminated the civil war in a moment as only He knows how. After a drinking bout in Harmala, to which Alexios had returned, a certain priest cut Alexios's throat with his own sword, which was lying by his side [before 6 January 1193]. When his head was carried back, the sebastokrator Alexios gazed at it intently; picking it up frequently by the golden hair with a horse's spur, he commented, "It was not altogether out of ignorance that the cities followed this man."

Among others, the emperor's brother Alexios, who reigned later, led an expedition. He did not engage Alexios in a single battle but encamped apart and at a distance in defense of the remaining territories that had not gone over to Alexios and checked the flow of defectors who would pass over to the resurrected Alexios. As the issue thus hung in doubt, and Alexios gained ground and waxed strong while the sebastokrator cowered and shunned face-to-face conflict, God, in a novel manner, terminated the civil war in a moment as only He knows how. After a drinking bout in Harmala, to which Alexios had returned, a certain priest cut Alexios's throat with his own sword, which was lying by his side [before 6 January 1193]. When his head was carried back, the sebastokrator Alexios gazed at it intently; picking it up frequently by the golden hair with a horse's spur, he commented, "It was not altogether out of ignorance that the cities followed this man."

In this way did this fellow receive his just dues for the crimes he wrongfully committed. When he armed Turks against Romans and inflamed those who came streaming in to him against his own countrymen, the wretch damaged the celebrated Church of Michael, the commander-in-chief of the divine and incorporeal hosts, in my city of Chonai; he defiled the all-hallowed tabernacle of God by entering with Turks, and before his very eyes the accursed man tolerated the destruction of the multicolored representations of Christ and the saints, the smashing by ax and stonecutter's tool of the holy pulpit, and the desecration and dashing to the earth of the all-hallowed table of offerings.""

Not many days later, another impostor took the same name and falsely claimed the emperor as his father. He stole secretly into Paphlagonia, and certain provinces went over to him. Theodore Choumnos, chartularios of the stables, was sent against him, defeated him in battle, and, taking him captive, killed him.

In addition, Basil Chotzas initiated a rebellion at Tarsia, near Nikomedia; his tyranny made strides for some time, but then he, too, was seized, blinded, and cast into prison.

Not only these but also others rebelled and so often that it is impossible to say how many times; springing up like giant Sown-men,"" and as hollow as blown bubbles, they would fall and burst. Isaakios Komnenos, Emperor Andronikos's nephew, escaped from prison and entered the Great Church, where he proceeded to incite the mob. When he was apprehended, he was suspended in the air and subjected to grievous afflictions to force him to reveal the names of his accomplices in his attempt to usurp the throne. His internal organs suffered damage and he died the next day.

Constantine Tatikios, who secretly set up a cabal of five hundred plotters and hid out in the City, thus escaping detection for a considerable time, was informed against, taken captive shortly afterwards, and his eyes were gouged out. And a certain ragged fellow, descended from the Komnenos family, who followed the same course as the others, was arrested and deprived of his sight.

The cause of these frequent rebellions was the feeble manner in which Isaakios governed the empire. Isaakios was absolutely convinced that he had received the throne from God, who alone watched over him. The emperor's indifference in directing the empire's affairs aroused the ambitions of power to open rebellion. Deceiving themselves, the majority of those who wished to reign often compelled those who gave ear to their appeals to tread the same path that Isaakios opened up straightway into a highway the evening that he killed Hagiochristophorites and hurried to the Great Church and reigned as emperor the next day. Because of their perverse judgment, they suffered grievously. In lieu of the purple robe they donned the double cloak of shame1G5 and were sometimes subjected to dark Death.

For the divinity does not like to change and direct the course of human events by the very same means or methods; expressing variety in the management and administration of all things in this world, at different times and in different ways He disposes of powers and removes authorities, attending even to the slightest detail."" And He delivers Pharaoh and his captains to the watery deep;" He cuts off the head of another with a sword wielded by a woman fair-cheeked and white-armed;"" another is delivered into the hands of the enemy and dispatched. Then there is he who goes mad and is reckoned as one dead in mind; condemned in the end to oblivion, he is carried out of the palace with malignant joy and escorted to the grave, crying out in a feeble voice that he longed only for the light of day and laid no claim to the throne; he is left thus to perish and as the worst of men is deservedly allowed to take the road to his death." Many succumbed to a gentle death and crossed over to the other side as though they closed their eyes in sleep. Then there are those who, because a horse neighed, mounted the throne. Another, leaving behind plow and furrow, put on the tebenna,' and a shepherd boy, taken from following the ewes great with young, was made a God-anointed king. But why should one relate all or most of the situations which manifold providence creates and alters for the benefit of each man?

The emperor, who was prone to anger and imagined great things about himself, grievously afflicted many at the slightest provocation, at times on the basis of mere suspicion or the insinuation of certain men. He ordered the immediate arrest of Andronikos Komnenos (he was the son of Alexios, born of the kaisar Bryennios and Anna, the daughter of Alexios, the first of the Komnenoi to reign as emperor), the governor of Thessaloniki, accused of lusting after the throne and of conspiring with the former sebastokrator Aiexios, Emperor Manuel's bastard son, who resided at Drama. The officials sent to perform this task met Andronikos, who was on his way back to the emperor. They did not carry out their orders, deeming it imperative not to scare away the prey as they came in sight so as to capture the quarry as in a weasel trap as he approached to enter Constantinople. Summoned before Emperor Isaakios, Andronikos was reproached for treachery. When he demanded the opportunity to refute the charges, Isaakios only pretended to agree to submit his case for adjudication. Andronikos was arrested without a trial and led away to prison, and shortly afterwards his eyes were gouged out.

Alexios, his alleged accomplice in this plot, was also apprehended and tonsured a monk under our supervision in one of the many soul-saving monasteries on Mount Papykios. Although there is much I could say about him, I will be mindful of brevity.

Not only was he tall and manly and extremely intelligent, bearing the exact features of his father, with strong arms topped by broad shoulders,"" but, above all, he was gentle and kind and affable. For these reasons, the much-enduring Andronikos, contemning his own daughter, betrothed her to the man, thus approving of the solemnization of an illicit marriage, if only to list him among his nearest relatives. He was more attached to him than to his own sons and gave thought to leaving him behind as his succes- sor.l"5 Later, he changed his mind and elected his son John instead, saying to those to whom he disclosed the secrets of [God's] purposes that the empire would not pass from alpha to alpha but would rather incline towards iota, and this according to divine plan. Once Andronikos changed his mind about Alexios, the ardor of his affection gradually cooled. No longer was Alexios's association desired as being of one mind with him, and he was treated with respect and honor only because he cohabited with his beloved daughter. After some time and for the reason recounted above, Andronikos also deprived him of his sight.'

Afterwards, when he was recalled by Emperor Isaakios and was restored to the rank of kaisar from that of sebastokrator, he would retire from the palace whenever possible to seek privacy, but even in so doing he was unable to attain a life without grief. Then the course of events took a turn for the worse. When he was about to be tonsured a monk against his will, he did not ask for a loaf of bread, a sponge, and a lyre as did a certain individual of old when he was sorely tried by a bitter and cruel fate:1177 bread to restore the tone of his human frame, weakened by lack of food; the lyre to accompany him as he sang plaintively of his misfortunes; the sponge to wipe away the stream of tears flowing from his eyes as though from a hollow rock. He bore his plight meekly, without grumbling against Providence or blaming the instability and fickleness of Fortune in human affairs, and he looked upon his confiscated possessions as though they belonged to another.

After we left Drama, we came to Mosynopolis and were about to ascend Papykios to perform the prescribed ritual for his initiation into the monastic life when, overwhelmed by emotion and unable to endure his inner anguish, he was wrapped in thought, and his face darkened. When I pressed him and asked the cause of this sudden change, he said, "It is not the habit that I fear, my good friend (for what dread does the exchanging of colors hold?), but I am terrified by the vows that I must take with the habit and by the fact that whoever has put his hand to the plow, yet still looks back frantically is in no way fit for the kingdom of heaven. "

Having said these and other things, for he was sententious, he donned the Christian habit against his will; heedless of the prayers and hymns, the long-haired Alexios was shorn of his locks and renamed Athanasios. One can only marvel at this event, since, I daresay, it did not take place fortuitously. Of all the monasteries on Papykios, he chose to reside in the one in which the former protostrator Alexios was shorn of his layman's locks when apprehended by Emperor Manuel for no evident reason what- soever, as we recounted when discussing his reign""' (for he abounded in riches and was competent in giving counsel and accomplished in getting things done). It seems that this Alexios Komnenos was condemned to suffer that the son's teeth be set on edge because the father ate sour grapes.

Three months had not elapsed before the emperor recalled him, proving once again that he acted out of caprice and was subject to sudden changes like the backward flow of the straits at Aulis. He received Alexios as his table companion and honored him with long chine of meat as Agamemnon of old had honored Aias; and urging him freely to lay hold of the food spread out before them, he would say repeatedly, "Eat, O Abbot."

Thus did Isaakios dispose of Alexios and Andronikos. And when Constantine Aspietes was strongly exhorted to pursue the war against the Vlachs with the troops under his command and replied only that he could not bear that his soldiers should contend against both famine and the Vlachs, two evils that were difficult to withstand, and that it was neces- sary to pay them their annual wages, Isaakios was unable to contain his anger. Straightway he removed him from his command and deprived him of his sight because he suspected that he would stir up the army on the pretext of taking up their defense.

The son of Andronikos Komnenos, whose fate we have recently discussed I know not whether he wished to fill up the measure of his father's revolt or whether he intended to come to his father's aidentered the Great Church shortly after his father was blinded in an attempt to seize the throne and be acclaimed by the assembled populace. But the manner in which he had entered was unknown to those who had congregated in the temple, and he was subdued as a rebel and deprived of the light of his eyes. Although another should have been the last to be punished for seeking the throne by going into the temple, he was the seal and the last of the rebels; henceforward, no one was to follow the same course.

As the affairs in the West had worsened and the Vlachs, together with the Cumans, made unremitting incursions, plundering and ravaging Roman lands, the emperor once again marched out against them [summer 1190 or 1191] and came to Haimos, bypassing Anchialos. Since nothing noteworthy was accomplished by the emperor's arrival, he brought the expedition to a close after two months. He found the fortresses and citadels there more strongly fortified than before with newly built walls marked off at intervals by crowned towers. The defenders without set their feet as harts upon high places,"" and as wild goats that haunt precipices shunned hand-to-hand combat. The emperor suspected an in- road by the Cumans (for the time of year was favorable for their crossing) and ordered a hasty departure (after summer].

Instead of leaving by the way he had come, he searched for a shorter route. As he was making his way to Beroe by descending into the valleys, he lost the greater part of his army, and were it not for the fact that the Lord was with him, he, too, would be dwelling in Hades."" In places the ground was so rough as to be almost impassable and to cross the moun- tain passes he had to squeeze his troops through holes and defiles where a mountain stream flowed. The vanguard was led by the protostrator Manuel Kamytzes and Isaakios Komnenos, the son-in-law of the future emperor Alexios; the Sebastokrator John Doukas, the emperor's paternal uncle, commanded the rear guard. Emperor Isaakios and his brother, the sebastokrator Alexios, were in charge of the main body in the center which was preceded by the pack animals and followed by the camp attendants. The barbarians, positioned on both sides of this narrow pass, were clearly in a position to do harm at any time.

Instead of leaving by the way he had come, he searched for a shorter route. As he was making his way to Beroe by descending into the valleys, he lost the greater part of his army, and were it not for the fact that the Lord was with him, he, too, would be dwelling in Hades."" In places the ground was so rough as to be almost impassable and to cross the moun- tain passes he had to squeeze his troops through holes and defiles where a mountain stream flowed. The vanguard was led by the protostrator Manuel Kamytzes and Isaakios Komnenos, the son-in-law of the future emperor Alexios; the Sebastokrator John Doukas, the emperor's paternal uncle, commanded the rear guard. Emperor Isaakios and his brother, the sebastokrator Alexios, were in charge of the main body in the center which was preceded by the pack animals and followed by the camp attendants. The barbarians, positioned on both sides of this narrow pass, were clearly in a position to do harm at any time.

The vanguard did not encounter the Vlachs along the narrow pass and went through without resistance. The enemy deemed it more advanta- geous to allow the first troops to proceed through without bloodshed and by outflanking both ends to rise together against the center. Thus they could smash the main body, which included the emperor, his attendants, and those of his noble kinsmen who followed him. And they were not disappointed in their expectations. Once the emperor had advanced a good distance over this rugged ground and there was no possibility of escape, the barbarians attacked with a mighty din. The Roman infantry was not remiss, but hastened so as not to be surrounded; they rushed up the steep slope and, with great toil and danger, repulsed the barbarians as they descended the mountain ridges. But the Romans were hard pressed by the throng and sustained many casualties from the stones rolled down upon them, and they gave way to flight, but slowly, not headlong, and only briefly; as men of strange speech who are forever grasping, they swarmed and fell upon the army in disorder.

As a result of the confusion, each man attempted to save himself, but they were as sheep shut up in a pen; whomever the enemy overtook, as well as all captives, they slew. No one put up a fight or was able to do so, and as many pack animals were killed, they say, as were Roman soldiers trapped in the defile because of the crush. As though caught in a net, the emperor attempted again and again to repulse the barbarian attack, but he could accomplish nothing, and he removed his helmet. At last, many of the mightiest warriors gathered around him, and thus he alone was able to escape while many perished. When he reached the regiments that had gone on ahead, he followed the example of David and offered up a thank-offering for his deliverance from danger to God, who overshadowed his head during this battle. The sebastokrator Doukas had seen that the way ahead was impassable, and had taken another route, thanks to a certain capable commander among his troops named Litoboj, whom he had lured away from the barbarian forces, and thus he came through the danger unscathed.

The emperor traveled by way of so-called Krenos and arrived safely at Beroe, where he met up with the troops who had gone on ahead unharmed. They had imagined that the worst had happened to him, for it was rumored that he had perished with the rest of the troops. For a few days longer he remained in these parts to dispel the false rumor and then returned to the queen of cities. The ill-omened rumor that was being bruited about concerning the emperor was superseded by another announcement proclaiming him victor, to which the emperor, in the manner of the Carthaginian Hanno, gave wings and let fly over the cities. But neither did Hanno long delight in his collection of singing birds which had been taught one phrase by striplings who sat patiently beside them and continually recited, "Hanno is a god." After the birds had been released in all directions so that their song would be about him everywhere, they no longer sang that Hanno was a god but warbled the melodies of birds as before. Nor did the emperor long enjoy the song of joyous tidings, for the loss of so many men filled the cities with wailing and the countryside with impassioned dirges.

After entering the queen of cities, the emperor, stung bitterly by these events, knitted his brows. Heretofore, when he had gone out against the barbarians, he had presumptuously applied the words of the prophet to himself, "He shall go forth and return with gladness: for the mountains and the hills shall exult to welcome him with joy, and all the trees of the field shall applaud with their branches; instead of the bramble shall come up the cypress, and instead of the nettle shall come up the myrtle. Often he would reveal those things hidden in the innermost recesses of his heart. He did not speak of the sins which we have committed in common and the abandonment of us all to the judgment of God (for the ear of the Lord has become heavy and hears us not,' and we have been given over to be chastised by a people foolish and unwise but instead Isaakios exacted retribution from those who followed Alexios Branas in rebellion,"" craving to deliver over the plunderers to such evils.

O the schemes and instructions of the Evil One which mislead some men to interpret these prophecies to mean that God delivers over to the barbarian nations, that rise up together in revolt, countless numbers of the pious in recompense for some fault of one of them, and allows these to be led away and killed as sheep for slaughter."' For which much- weeping Jeremias has lamented in full measure the captives, the slain, and those removed to distant lands where the name of Christ is not invoked.""

Isaakios expounded on these things in an extraordinary manner and also made it clear that he would become the sole ruler, that he would suck the milk of the Gentiles,"" and that he would be the one to liberate Palestine and acquire the glory of Lebanon, slaughtering and plundering the Ismaelites beyond the Euphrates and sweeping away the barbar- ians round about. He added that the rulers under him would not be like those of today, but that they would acquire absolute power and eat the wealth of nations"" and drain the marrow, 1201 that they would be ap- pointed to the very same authority and distinction as that of kings and governors.

It was said that Isaakios had appointed as instructor in all these things Patriarch Dositheos, who, like a moth, entered unseen and corrupted his nature, which was inclined toward novel tales, with vain babblings; in the manner that wet nurses lay new-born babes on their stomach to relax them, he made the emperor recline in order to enervate him with the enchantments of fabulous tales. He told him that Fate, without Isaakios lifting a hand, had decreed that all kingdoms should submit to him in the same way that the artists of old portrayed Timothy as he lay asleep while Fortune gathered cities in a fishnet to hand to him.

Even more astonishing was his express statement that Andronikos Komnenos, whom Isaakios had dethroned and delivered over to a grievous death, had been destined to reign over the Roman empire for nine years, but that God had contracted his nine-year reign to three because he was a malefactor; indeed, these six years were cast over the purple robe of Andronikos's reign like a tattered garment, and he was destined during these three years to be not at all good or temperate, nor was he in any way made glad by good deeds, so that his evildoing by necessity affected and disposed his nature. Whether these things have resurrected the rotted Destiny of old and prove the existence of Necessity, and whether they vindicate Andronikos of blame for his baneful rule, I leave to the speculation of those who wish to do so. Since the six years had passed, it was shown from the events themselves that it is not a matter of time but a peculiarity of the mind which prevents some from attaining that which they desire, for although Isaakios promised his subjects greater blessings in the years to come, he did nothing better than he had done in the past.

Elated by their endless victories against the Romans, the Vlachs, who had captured splendid treasures and all kinds of armament from the Romans, were irresistible in their assaults. No longer did they only attack and plunder villages and fields; now they took up arms against lofty- towered cities. They sacked Anchialos, took Varna by force, and ad-vanced on Triaditza, the ancient Sardica, where they razed the greater portion. They also emptied Stoumbion'203 of its inhabitants, and at Nis, they carried away no small measure of men and animals.

Although the emperor was compassed about as a honeycomb by bees and had no one to come to the aid of those who were grievously afflicted, and in the end no one to provide assistance, he divided the army under several commanders. Thus he recovered Varna; Anchialos he fenced with towers and installed garrisons within. It does not appear that these successes were the result of imperial foresight, but these cities here- after proved to be superior to the enemy.

saakos marched out towards Philippopolis at the time of the autumnal equinox [1191 or 1192], taking along the women of the court (for it was possible to do so), and checked the inroads of the Vlachs and Cumans. He also set out against the Zupan of the Serbs for having ravaged the land and destroyed Skoplje. When the two armies clashed at the Morava River, the barbarians gave way and many, submerged in the waters and transfixed by spears, perished 12111 in the pursuit that followed. Bypassing Nib, he arrived at the Sava River, where he met with his father-in-law Bela, king of Hungary. After a stay of many days, he returned again to Philippopolis, avoiding the Haimos, and entered the megalopolis.

Isaakios wanted to change the administration of the province of Philippopolis because of the unending sufferings visited on the inhabitants. He dispatched his cousin Constantine'20" and appointed him general and dux of the fleet. Although he was but a mere lad, high-spirited in the manner of lion cubs which, from the very moment of birth, show forth their pride, their shaggy manes, and their sharp claws, so he trained his troops to obey and fear him that they readily submitted to his orders and re- sponded to a mere nod or thought. He commanded his troops, therefore, with a native cleverness. If, at times, because of his youthful impetuosity, he fell short of his responsibility, his experienced subordinate commanders would hold him in check, admonishing him not to overstep the rules of tactics. The rebel Vlachs cowered in fear of him and were more panic-stricken at the sight of him than of the emperor. Often when Peter and Asan went out with the intention of ravaging the lands around Philippopolis and Beroe, they did not escape Constantine's notice, and he pursued them, routing the battalions,""' so that they did not make as many sallies as before.

But whereas Constantine should have pursued these successes for the benefit of the fatherland and its cities, he did just the opposite. Because he was young, he was elated at these minor achievements and became erratic in his behavior. He began to win over the commanders who were associated with him and those of the native troops he knew to be of noble birth and expert in military affairs. With some small support from these men in the achievement of his objective, he chose the imperial robe instead of that of the general and put on his feet the purple-dyed boots in readiness to take the throne by force. By way of letters he informed his wife's brother, the grand domestic of the West, Basil Vatatzes, of his actions. But Vatatzes did not praise Constantine's daring, or take heed of his puerile actions and the letters which he had presumptuously sent him at Adrianople. Instead, he mocked his untimely and foolish ambition and mourned him as though he had already perished-a fate which quickly ensued.

Constantine set out from Philippopolis for Adrianople, intending to make his brother-in-law an accomplice in the deed against his will. Upon reaching Neoutzikon, as it is called (this is a place on the border of both provinces; I speak of Adrianople and Philippopolis) he was seized and given up to the emperor by those who had prodded him to rebel and had proclaimed him emperor. In defense of their actions, they told the emperor that they had submitted to and inclined towards the rebel only because at this time and in these circumstances there was nothing else they could do but change sides and join him. (They saw that to oppose the dictates of Constantine would not have been without danger and physical harm to themselves, for he was irascible towards the generals who stood before him, and those who did not abide by his decisions suffered his bared sword.) By their present action, they pointed out, they had demonstrated to the emperor the proof of their loyalty. The emperor saw through the subterfuges and specious excuses of these untrustworthy men, but he praised their action, nonetheless, because it was advanta- geous to him; he did not openly punish any of the accomplices of Con- stantine, whom he blinded.

So greatly did the Vlachs rejoice, and Peter and Asan exult, over the fate of Constantine that they spoke of making Isaakios emperor over their own nation, for he could not have benefited the Vlachs more than by gouging out Constantine's eyes. This showed how clever they were in these matters, and they sneered at the progressive decline of Roman affairs as they succumbed more and more to an evil lot. They prayed that the Angelos dynasty would be granted a reign of many years over the Roman empire and earnestly entreated the Divinity that, if it were possible, they should never see death""' or be removed from the throne. These accursed indulged in predicting future events, giving as their reason that as long as the Angeloi reigned, the successes of the Vlachs would increase and be magnified, that they would acquire foreign provinces and cities, and that rulers and princes would come forth from their loins.121 I know not whence and how they arrived at such elaborately worked-out conclusions.

The Vlachs, therefore, set out with a Cuman battalion to sack a for- tress, plunder villages, or lay waste cities. They destroyed everything on the way, one time attacking Philippopolis, at another besieging Sardica, and at other times assaulting Adrianople. Although the Romans prosecuted the war slothfully, whenever they opposed or engaged the enemy in battle they afflicted them in good measure.

The emperor, like a runner on the long course or racing in the stadium, stopped running the course of excellent government right at the turning post. For he was unable to complete many circuits around the track of virtue; as soon as he began to tire, the intensity of his efforts flagged and his praiseworthy intention was wholly enervated. Transferring the bridle and reins of the empire from one official to another so that he might avoid the weighty responsibility of governing the state, he finally handed over the conduct and administration of all public affairs to his maternal uncle, Theodore Kastamonites.

This man, extremely skillful in wielding power and especially in the collection of public taxes, was also eloquent in speech. Promoted to logothete of the sekreta, he conducted the affairs of state as though he were emperor so that all ministers carried out his every order almost without question. Kastamonites, who suffered a disease in the joints of his legs, was often carried in to the emperor on a folding chair by two bearers who were like the handles of amphorae of wine; after discussing useful topics with the emperor or, rather, exploiting the state of Roman affairs, of which he rendered a brief account, he was carried out again. The people, the state senate, and the emperor's blood relations followed behind him in escort, and surrounding the chair as though it were a casket, they bewailed not him but their own fortunes. Nothing was done without his knowledge, and no one in authority was allowed to sit down with Kastamonites, but must stand in his presence in a servile attitude. The emperor was not troubled in the least by all this. Seeing his own glory passing unpropitiously to another and his power being snatched from him, he perceived nothing improper whatsoever in this absurdity and gave his approval to these developments without any evident justification. When Kastamonites went in procession on horseback, Isaakios allowed him to have the imperial purple trappings and to wear the purple military cloak; he was allowed to sign the public decrees and rescripts in dye of the same color. The state of affairs had truly taken a strange turn, inconsonant with Nature herself, until a certain merciful disease that showed compassion for those who took no pity on themselves befell the man. Its spreading noxious matter affected the joints of his body and afflicted his reason even more strongly.

It was the fifteenth day of the month of August when Kastamonites, escorted with great festivity by a huge crowd of officials, visited the Monastery of Pantanassa by way of the agora to celebrate the rites of the death of the Mother of God and for the first time heard himself acclaimed despot and emperor, for this is how flatterers and wheedlers choose to address those who rule. It appeared the more perceptive of those who had assembled that the novelty of what he heard brought on an attack of epilepsy. A judge of the velum, who was standing nearby (I purposely omit his name), loosened his clothing and bound the calves of the logothete's legs with his waist belt in an attempt to stem the upward flow of matter. While Kastamonites fell into a state of delirium, the judge of the velum became the butt of hearty laughter because his garments were undone, and he had shown himself to be so naive. Kastamonites briefly recovered from his cachexia and spent the rest of the day in better spirits, but then he fell ill once again, and a few days later he died. The disease had spread to other parts of the body, and his buttocks were covered with sores.

Next to beauty, ugliness appears to be even more conspicuous. Following Kastamonites' death, a youngster, who should have been studying with an elementary schoolmaster, writing tablet in hand, succeeded to the emperor's favor.

While the one departed this life from among us, a small boy [Constantine Mesopotamites] assumed the administration of public affairs less than a year after he had put down pen and ink; not only did he lead the emperor about in the manner of a leader whale12" but he also took charge of troop registers as though he had been trained from infancy to adminis- ter momentous affairs, or as if even before birth he had been entrusted with worldly concerns as was Sibyl, about whom it is said that as soon as she issued from her mother's womb she began to philosophize about the composition of the universe. He assumed far greater power than that of Kastamonites and deemed lawful whatever the emperor desired.

He was simply a bumblebee or a mosquito buzzing around the lion's ear or a black-skinned ant-man leading about the elephant, the most ponderous burden on earth, or a fine rope pulling a camel by the nose; one could say, and not without some elegance, that the thick earwax that formed in the emperor's auditory canal blocked out the flow of sound from both sides, or that small is the side door, strait is the little gate, and narrow the way leading into the palace. The wide entrance gates, through which petitioners formerly visited the emperors, were tightly shut, and those who attempted to enter through them were like those foolish virgins, for there was no one to open to him who knocked. 1121 Should someone late in the day set eyes upon those who persisted in knocking at the closed gates, he would answer no question but instruct them to go to the side gate where they would find easy entrance if they put some money in the fold of their garment or in their double-folded mantle. This aged youth strove diligently to be loved beyond measure by the emperor and to be reckoned indispensable; he was sophistic in his character, quick in repartee, capricious, secretive, and crafty, as was evidenced by the growth of his eyebrows in a single line without separation.1221 Moreover, his aptitude for trade and his insatia- ble gathering in of unjust gain endeared him to the emperor; he stealthily snatched up coins from all kinds of business dealings and set ambushes for those under investigation, and he also had a passion for round cakes, ravened for melons, and craved to taste all the delicious eatables of the earth.

Let the narrative return now from its digression to the track whence it had set out from the beginning. To make a long story short, the actions of this emperor during the time he remained in the queen of cities may be clearly articulated as follows. Daily he fared sumptuously and served up a Sybaritic table, tasting the most delectable sauces, heaping up the bread, and feasting on a lair of wild beasts, a sea of fish, and an ocean of deep-red wine. On alternate days, when he took pleasure in the baths, he smelled of sweet unguents and was sprinkled with oils of myrrh, and he surpassed the likeness of a temple with his fine, long robes and curled hair. The dandy strutted about like a peacock and never wore the same garment twice, coming forth daily from the palace like a bridegroom out of his bridal chamber or the sun rising out of a beauteous mere.

As he delighted in ribaldries and lewd songs and consorted with laughter-stirring dwarfs, he did not close the palace to knaves, mimes, and minstrels. But arm and arm with these must come drunken revel, followed by sexual wantonness and all else that corrupts the healthy and sound state of the empire. Once at dinner Isaakios said, "Bring me salt." Standing nearby admiring the dance of the women made up of the emperor's concubines and kinswomen was Chalivoures, the wittiest of the mimes, who retorted, "Let us first come to know these, 0 Emperor, and then command others to be brought in. At this, everyone, both men and women, burst into loud laughter; the emperor's face darkened and only when he had chastened the jester's freedom of speech was his anger curbed. In the country he chased after the delights of climate and location at the resorts and returned to the megalopolis only at intervals; from time to time he made his rare appearance like the bird called the phoenix.

Above all, he had a mad passion for raising massive buildings, and carried away by the magnitude of his duty, he pounced upon the City's beloved structures. Within both palace complexes he built the most splendid baths and apartments; along the Propontis he constructed extravagant buildings, and, filling in the sea with earth, he formed islets. To erect a tower which, he contended, would defend the palace of Blachernai as well as serve as his residence, he razed the ancient churches that stood neglected in the eastern district and made a desolation of most of the outstanding dwellings of the queen of cities; there are those who pass by to this day and shed tears at the spectacle of the exposed foundations.

He even leveled the magnificent building of the genikon. He also pulle down the renowned house of Mangana with no regard for the building's beauty or fear of the trophy-bearing martyr [St. George] to whom it was dedicated.

In his restoration of the Church of Michael, the commander-in-chief of the heavenly hosts, he brought to Anaplous the most beautiful polished marble slabs embroidered with multicolored veins, which covered the floors and overlaid the walls of the palace buildings. As many painted and mosaic images of the archangel, the works of ancient and marvelous hands, as were sheltered in the City or set up in villages and provinces as talismans, he gathered together in the same shrine. This emperor's zealous exertion to bring back from what today is called Monemvasia the image of Christ being led away to his crucifixion, an admirable work of art and beauty, was not the least of his mad passions: for he put all his hopes in this image until he took possession of it through deceit. This undisguised undertaking was not wholly without danger. He also trans- ported there the broad and high bronze gates that formerly barred the entrance of the Great Palace and in our day secured the prison that took from them its name, Chalke. He stripped bare the renowned church called Nea in the Great Palace of all its sacred furniture and holy vessels. As a result, he pridefully gave himself airs and plumed himself as though no other had ever built such marvelous works. He thought that removal was the same as augmentation, and transposition the same as addition, and he preferred the shadow-filled depiction of the good deed which paints the form of piety but sketchily or not at all; of a truth, he believed that the Divinity would be not angry but pleased should this temple be despoiled of its former splendor and left to become a nesting place for birds and the habitation of hedgehogs while another was consecrated with relics removed from their rightful place and magnificently embellished with ornaments taken from elsewhere.

He was, to put it mildly, brazen enough to defile the sacred vessels which he snatched from the holy churches and used at his meals. When carousing, he would clasp the goblet-like votive offerings to God decorated with precious gems and made of refined gold that hung in the tombs of the emperors, and there were carried about exquisite, elegant pitchers for hand washing which the Levites [deacons] and priests use to cleanse themselves when they approach the Holy Mysteries. Removing the precious adornments from the holy crosses and the tablets of the undefiled sayings of Christ,"" he used these to make necklaces and collars, and at his pleasure shamelessly fastened these to his imperial robes.

Towards those who attempted to persuade him that such actions did not accord with a God-loving emperor upon whom piety had descended from his forebears, and that such deeds were clearly acts of sacrilege, he became indignant, irritated, and he rebuked them for being manifestly.

The house of the sebastokrator Isaakios, which was situated on the slope of the harbor of Sophiai, was made over into an inn. There, board and lodging were provided for a hundred men, and stables were built for the same number of pack animals; transients were daily taken in as guests and remained on for many days without paying any money. He converted into a hospital the imperial edifices which Emperor Andronikos had built near the Church of the Forty Martyrs. In addition, he purchased from its owner what is known as the House of the Grand Droungarios and likewise set it apart as a rest home for the infirm, sparing nothing that was needed for the recovery of the sick. And when the northern region of the City was destroyed by fire, he dispensed monetary relief to those who lost homes and possessions. During his reign he distributed five hundred pounds of gold to the citizens. With the arrival of Holy Week, during which the Passions suffered by the God-Man on our behalf are commemorated with reverence, he succored many widows for the loss of their husbands by bestowing benefactions upon them, and he provided virgins with the requisites for the nuptial torch, bridal chamber, and wedding song.

Not only did he lavish gifts upon individuals, households, and kins- men, he was also a benefactor of whole cities by remitting taxes. In other words, he rejoiced in alms giving and was eager to expend the collected devoid of intelligence and woefully ignorant of the good. He contended that all things are permissible to reigning emperors and that between God and ruler in the government of earthly affairs there is nothing disparate or contrary which sets them at variance in the manner that affirmation is opposed to negation. To assure them that these actions were beyond reproach, he cited the example of Constantine, the most excellent and the very first of the Christian emperors, who fastened to his horse's bridle one of the nails by which the Lord of Glory was transfixed to the accursed tree and attached a second nail to his helmet. He intentionally ignored that the emperor and author of the faith121' did these things to demonstrate to the Hellenes, who looked upon the preaching as foolishness, that the Word of the Cross was the power of God.

Adulterating the silver, he minted debased coinage and gathered in revenues not altogether without reproach; he both increased the collection of public taxes and squandered the monies in riotous living. And he hawked the public offices as venders peddle their fruit. At times, however, in accordance with the apostolic injunction, he would send into the provinces without purse or scrip1240 officials who, he knew, would dispense to the just man his portion and not be beguiled by gold; neither would they stash away the collections in their homes but would deposit the adjusted debt in the public treasury.

As none before him, he lavished gifts upon churches, shrines, oratories, and holy monasteries. Those edifices which in time had fallen into disrepair he restored, and those whose splendor had faded he embellished with adornments of mosaics and paintings. He had such faith in the Mother of God that he poured out his soul to her icons. a greater number of these he ha overlaid with gold and adorned all around with precious gems and set them up as votive gifts to be venerated in those, churches where the pious most often congregate. revenues, using both hands to empty out what poured in, whence the idea of gathering in monies from sources which were not always justified slipped in secretly and surreptitiously stole into his mind. The majority, who did not suspect that the enormous expenditures approached prodigality, were assigned the task of contriving novel tax collections, kneading together the ill-gotten and illegal revenues with those justly collected like millet being planted in a cultivated orchard or the anemony with the rose. Although prone to anger, he was not devoid of a sympathetic nature, and often compassion moderated his wrath and his disposition was altered towards goodwill. Moved to pity by the misfortunes of men, he would measure out to each individual the mitigation of his sufferings.

Because he did these things and other such things which we have passed over in our narration, he thought that his throne was more firmly established than the sun in the heavenly sphere, or that it was as the stem of a palm tree that grows green from the scent of water, or that like the towering cedar of Lebanon it would be preserved through the cycles of many long years. Another would have been suspicious, would have chosen and embraced the good part, not only giving the seven days their portion but also keeping the mystery of the eighth day before his eyes; and even though as lord he could have turned the scale both ways, he would ever be inclined towards the better part, swimming readily against the enemy but not sinking beneath the surface. But God did not wish this to be. Who has known the mind of the Lord? Or with whom has He taken counsel? The Divinity, having taken forethought for the man's removal, roused him to noble deeds and the highest zeal, and by endowing him with courage, made him beloved by the many even after his deposition from the throne.

Isaakios could not endure the raids of the Cumans and the pillaging of the Vlachs and decided to wage his own war against the adversary. And he was smitten by the debacle of Alexios Gidos and Basil Vatatzes, the commanders of the eastern and western divisions, who, on engaging the enemy [1194] near the city built by Arkadios [Arkadiopolis], accomplished nothing useful. Moreover, Gidos fled in disarray, losing the better part of his army, while Vatatzes perished along with his troops. There- fore, Roman troops were levied and placed on the military registers and fit mercenary troops were enlisted. Dispatching envoys to his father-in- law, the king of Hungary, Isaakios requested auxiliary forces; the king gladly consented to help and agreed to send troops by way of Vidin.

He collected a sufficient number of troops, supplied himself with fifteen hundred pounds of gold and more than six thousand pounds of silver, provided other useful supplies for the army and then departed from the queen of cities during the days of March [1195]. His trust he put in God, and he set his face against the enemy' like a solid rock, making as a condition of his return the completion of his task; should it be fortunate, he would return, thanks to God, but should it be ill-fated (heaven forbid!) he would continue to rely upon the judgments of Him who uses the rod of sinners to chastise the lot of the righteous.

It was with such zeal that he set out to meet supreme danger; the hand which is stretched out over all things and turns the scale remained sus- pended on high; neither was the wrath of the Almighty turned aside, since the Vlachs prevailed in all the battles they fought. Thus did the eye of the emperor look upon the provoking rebels, and the issue of rebellion was far removed from his mind. Because he who was to overthrow him from power was near at hand and related to him, he was overlooked, and since the stumbling block at his own hearth was no annoyance, he leaped over it. There is nothing novel in this, since the evils that sprout alongside or amidst the virtues the majority of us men neither choose to see nor are able to see as we should. I forebear to say that Nature has implanted within us a passion for our own. Thanks to the bonds of affection it yields to and shows weakness before their bad habits and at times is constrained to do the same for friends. Not easily controlled, it gives its ear to those who pour out a flood of words, as into a perforated cask, and recount the misfortunes we have endured.

The emperor was warned by many that his brother Alexios plotted against his throne and his life, but the latter concealed his hatred for his brother behind a screen of affection, and so Isaakios dismissed these reports as so much nonsense; he did not bring forth the Herakleian touchstone to investigate and examine the charges against his brother but bitterly accused those who made them of wanting to expunge his love for his brother, the love that was indelibly branded into the depths of his soul, inasmuch as Alexios was the only one to have remained unharmed by the destroyer Andronikos.

When Isaakios arrived at Rhaidestos beside the sea and celebrated the preeminent feast of our Lord's Resurrection, he sacrificed and ate the mystical pascha [2 April 11951. 121' Here he met with Basilakios. The latter led a strange life and was believed by everyone to have the power to prophesy, to foresee the future, and the masses streamed towards him in the manner of worker ants moving in and out of an ant hill or of visitors to the oracles of Ammon and Amphiaraos in antiquity.1257 But his predictions were never accurate: his words were erroneous, contradictory, and enigmatic. Although many of the things he contrived were laughable, he attracted nonetheless the cattleman, the plowman, and the rower. He would examine the breasts of women who came to him and scrutinize their ankles and make nonsensical observations and vague predictions. He did not reply to the majority of questions put to him by those who came, and his successes were achieved on false pretenses and by moving from place to place. Certain Greek women, his disciples and kinswomen, mad with passion and inebriated, would relate to those who drew near that the rites performed by Basilakios foretold the future, and they interpreted his silence as proof that he was a wise oracle. This man, therefore, appeared to many, as I have said, to be a prophet and diviner of future events. There were those women who asked indecent questions and wore immodest frocks to make sport of him, but the sober-minded held him to be a curiosity, a buffoon, and a prattling old man. And there were those, among whom I was included, who said that he possessed a spirit of divination.

When he appeared before the emperor, he neither heeded his great power nor replied to his salutation of "Hail, 0 Father Basilakios," or even greet him in return by silently nodding his head, but bounding about hither and thither like some frisky colt and making frenzied gestures, he insulted those present, not even sparing the emperor. When at last he put an end to his fitful motions, he extended his hand in which he carried his staff and damaged the emperor's painted image set up on the wall of his private chapel, mutilating the eyes. Then he rushed forward and snatched the emperor's cap. These things then did Basilakios do. The emperor, who regarded the man as quite mad, removed himself thence. Although those who were assembled and had witnessed these events with their own eyes did not consider this to be an auspicious portent of things to come, others did not think that these omens augured a baneful outcome; more- over, the general opinion of Basilakios was reinforced, since it was, as I have stated, ambiguous and disputable in most cases.

When Isaakios arrived at Kypsella, he divided his forces into companies while he awaited the arrival of the other troops. His brother, who over a long period of time had lay in wait to seize the throne, then brought to light those things that lay hidden in his heart and that secretly smoldered in his breast. The emperor was fond of the chase, and as he prepared to mount his horse [8 April 1195], he sent for his brother Alex- ios to join him and take delight with him in the grass green and flowery meadows in that place. Alexios, who was preparing to carry out the task at hand, declined the invitation on the pretence that he was ailing and being made ready to have a vein opened for bleeding.

So Isaakios set out without him and happily went on his way. When Alexios had observed that the emperor had advanced some three stades from the tent, he and his closest friends and fellow conspirators who had plotted with him to achieve his purpose entered the imperial pavilion. These were Theodore Branas, George Palaiologos, John Petraliphas, Constantine Raoul, Manuel Kantakouzenos, and many other perverse and weak-minded men, the emperor's kinsmen as well as a swarm of the common herd who for a long time had roamed gaping through the sebastokrator's banqueting hall, rejoicing at the complete change about to take place in the government. As soon as they got wind of the revolution, all the divisions of the army defected, as did those who were inclined towards Isaakios, such as his attendants and domestics, and these were joined by those who had been raised to the dignity of senator.

At first, the emperor could hear only unintelligible sounds, but soon he observed a huge throng running towards the imperial pavilion and heard his brother being acclaimed emperor. Shortly afterwards messengers told him of the shameless coup d'etat and he came to a halt.,_ whereupon he made the sign of the cross over himself and cried out, "Be merciful to me, 0 Christ, my Emperor!" and invoked God many times to save him from this hour. Pulling out his pectoral icon of the Mother of God, he embraced it many times, all the while confessing his sins and promising to make amends, and in anguish of heart he prayed to escape the impending evils. As he saw that his appointed captors gave-- free rein to their horses in their determination to seize him, he took flight. At great risk he crossed the deep-eddying river [Maritza] which courses through the plain and then kept to the road, for he could find no clear avenue of escape. In his desire to avoid certain destruction, he determined to ride as fast as possible to elude the furious onrush of his followers, but when he reached Stageira, now called Makre, he was apprehended by a certain Pantevgenos and turned over to his pursuers.

At the Monastery in Vera founded by Isaakios, the father of Emperor Andronikos, he looked upon the sun for the last time, and his eyes were soon gouged out. As to whether retribution was requited of him at this place by divine Nemesis, I leave for others to ponder. Providence, which administers everything for the best, desires that avengers treat their most despicable enemies with humaneness, since they must suspect that power is never permanent, that one political action which ungirds sovereignty often is reversed with a new throw of the dice.

After this calamity, no food was brought to Isaakios for many days. To alleviate his chastisement he was incarcerated temporarily within the palace and later transferred to the opposite shore of the Double Column, where he drained to the dregs the rustic life, living on wine and measured bread. His brother ascended the throne peacefully and without factional strife, and the two could be compared to the Dioskouroi who agreed to set and rise on alternate days in the firmament of the empire.

Isaakios reigned over the Romans for nine years and seven months. He had a ruddy complexion and red hair, was of average height and robust in body, and was not yet forty years old when dethroned.

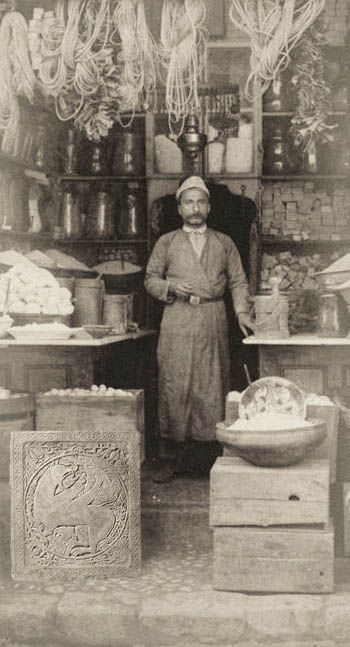

Shops operated from columned porticos. Merchandise was offered on the street and within the store. Most shops were family operated.

Shops operated from columned porticos. Merchandise was offered on the street and within the store. Most shops were family operated. Constantinople was served by aqueducts to fountains and open air cisterns around the city. Fountains would have been decorated with ancient statues and sculpture like this. People drew much of their water from wells that accessed underground cisterns.

Constantinople was served by aqueducts to fountains and open air cisterns around the city. Fountains would have been decorated with ancient statues and sculpture like this. People drew much of their water from wells that accessed underground cisterns. The city had many gardens and even vineyards. Many of the streets were arcaded.

The city had many gardens and even vineyards. Many of the streets were arcaded.

The streets were full of people who delivered fresh and prepared foods or every kind. Water was also delivered right to your door.

The streets were full of people who delivered fresh and prepared foods or every kind. Water was also delivered right to your door. Constantinople was a late antique city of columns, forums and paved streets. Some streets and shops were lit at night.

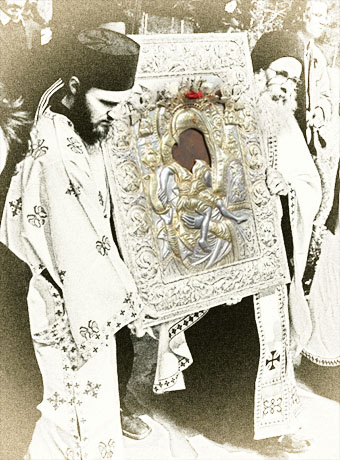

Constantinople was a late antique city of columns, forums and paved streets. Some streets and shops were lit at night. There were many priests, monks and nuns. Aristocrats and rich merchants founded and endowed convents for the female members of their family to retire to. Not all of them became nuns. Women could spend long periods of time living in nunneries as places of refuge.

There were many priests, monks and nuns. Aristocrats and rich merchants founded and endowed convents for the female members of their family to retire to. Not all of them became nuns. Women could spend long periods of time living in nunneries as places of refuge. The city was the destination of pilgrims from all over the world. Every year, at Easter, the relics of Christ's Passion were exhibited in Hagia Sophia. Hundreds of thousands of people viewed them.

The city was the destination of pilgrims from all over the world. Every year, at Easter, the relics of Christ's Passion were exhibited in Hagia Sophia. Hundreds of thousands of people viewed them. Women were very involved in the production of textiles and clothing. They also operated shops.

Women were very involved in the production of textiles and clothing. They also operated shops. Fashions changed rapidly in the 12th century. Men's fashions could be outlandish - even foppish. All men wore hats or turbans. Belts were decorated with buckles of bronze, silver and gold.

Fashions changed rapidly in the 12th century. Men's fashions could be outlandish - even foppish. All men wore hats or turbans. Belts were decorated with buckles of bronze, silver and gold. Imperial clothing was made in specialized shops near the Great Palace.

Imperial clothing was made in specialized shops near the Great Palace. Women wore beautifully ornamented clothes. Much of this work was done at home. Byzantine women were expert seamstresses and tailors.

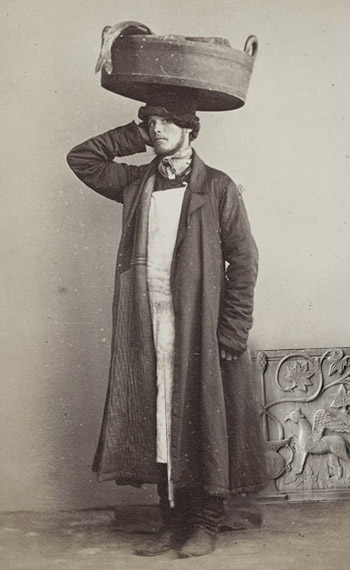

Women wore beautifully ornamented clothes. Much of this work was done at home. Byzantine women were expert seamstresses and tailors. Hauling water and food was a hard job which was done by both men and women. Many of them could serve you wine, bread or fried delicacies in the streets. Some of them were attached to taverns.

Hauling water and food was a hard job which was done by both men and women. Many of them could serve you wine, bread or fried delicacies in the streets. Some of them were attached to taverns. Most Constantinople homes had courtyards. Residents would get water here, do cooking or their washing here. Since people normally lived in family compounds or near their work these activities could be communal.

Most Constantinople homes had courtyards. Residents would get water here, do cooking or their washing here. Since people normally lived in family compounds or near their work these activities could be communal.

Emperor Isaakios anchored the succession of his family on the three children begotten of his former marriages: two females and one male. He tonsured the older daughter a nun and at great expense converted the so-called house of Ioannitzes into a nunnery (Empress Xene wanted very much to do this after the death of her husband, Emperor Manuel) to cloister her within, setting her apart and consecrating her as a ewe lamb. His second daughter he sent to wed the son of Tancred [1193], the king of Sicily, who had succeeded William after his death; the latter, as we have related, was he who waged war against the Romans on both land and sea. He educated his son Alexios as heir to the throne, although he never imagined that his own life would come to an end so soon, nor did he suspect his own fall from power, forecasting without doubt that he would reign for thirty-two years as though he could forsee the divine will or that he himself could stake out the limits of life which God had put in his own power.

Emperor Isaakios anchored the succession of his family on the three children begotten of his former marriages: two females and one male. He tonsured the older daughter a nun and at great expense converted the so-called house of Ioannitzes into a nunnery (Empress Xene wanted very much to do this after the death of her husband, Emperor Manuel) to cloister her within, setting her apart and consecrating her as a ewe lamb. His second daughter he sent to wed the son of Tancred [1193], the king of Sicily, who had succeeded William after his death; the latter, as we have related, was he who waged war against the Romans on both land and sea. He educated his son Alexios as heir to the throne, although he never imagined that his own life would come to an end so soon, nor did he suspect his own fall from power, forecasting without doubt that he would reign for thirty-two years as though he could forsee the divine will or that he himself could stake out the limits of life which God had put in his own power. Giving in to the youth's persistent entreaties, the Turkish ruler did not even then limit his excessive demands, but issuing a special letter of the sultan which the Turks called mansur, he allowed him to enlist with impunity as many of his subjects as he could. Alexios departed, and when he showed the letter to the Turks, he attracted the amir Arsan and many others who habitually plundered the Roman provinces. Within a short time, eight thousand troopsTM62 chose to follow him to war against the cities along the Maeander. Some capitulated without a fight, while those that resisted were completely destroyed. He even laid waste the planted fields and, as a result, was called Crop-burner.

Giving in to the youth's persistent entreaties, the Turkish ruler did not even then limit his excessive demands, but issuing a special letter of the sultan which the Turks called mansur, he allowed him to enlist with impunity as many of his subjects as he could. Alexios departed, and when he showed the letter to the Turks, he attracted the amir Arsan and many others who habitually plundered the Roman provinces. Within a short time, eight thousand troopsTM62 chose to follow him to war against the cities along the Maeander. Some capitulated without a fight, while those that resisted were completely destroyed. He even laid waste the planted fields and, as a result, was called Crop-burner. Among others, the emperor's brother Alexios, who reigned later, led an expedition. He did not engage Alexios in a single battle but encamped apart and at a distance in defense of the remaining territories that had not gone over to Alexios and checked the flow of defectors who would pass over to the resurrected Alexios. As the issue thus hung in doubt, and Alexios gained ground and waxed strong while the sebastokrator cowered and shunned face-to-face conflict, God, in a novel manner, terminated the civil war in a moment as only He knows how. After a drinking bout in Harmala, to which Alexios had returned, a certain priest cut Alexios's throat with his own sword, which was lying by his side [before 6 January 1193]. When his head was carried back, the sebastokrator Alexios gazed at it intently; picking it up frequently by the golden hair with a horse's spur, he commented, "It was not altogether out of ignorance that the cities followed this man."

Among others, the emperor's brother Alexios, who reigned later, led an expedition. He did not engage Alexios in a single battle but encamped apart and at a distance in defense of the remaining territories that had not gone over to Alexios and checked the flow of defectors who would pass over to the resurrected Alexios. As the issue thus hung in doubt, and Alexios gained ground and waxed strong while the sebastokrator cowered and shunned face-to-face conflict, God, in a novel manner, terminated the civil war in a moment as only He knows how. After a drinking bout in Harmala, to which Alexios had returned, a certain priest cut Alexios's throat with his own sword, which was lying by his side [before 6 January 1193]. When his head was carried back, the sebastokrator Alexios gazed at it intently; picking it up frequently by the golden hair with a horse's spur, he commented, "It was not altogether out of ignorance that the cities followed this man." Instead of leaving by the way he had come, he searched for a shorter route. As he was making his way to Beroe by descending into the valleys, he lost the greater part of his army, and were it not for the fact that the Lord was with him, he, too, would be dwelling in Hades."" In places the ground was so rough as to be almost impassable and to cross the moun- tain passes he had to squeeze his troops through holes and defiles where a mountain stream flowed. The vanguard was led by the protostrator Manuel Kamytzes and Isaakios Komnenos, the son-in-law of the future emperor Alexios; the Sebastokrator John Doukas, the emperor's paternal uncle, commanded the rear guard. Emperor Isaakios and his brother, the sebastokrator Alexios, were in charge of the main body in the center which was preceded by the pack animals and followed by the camp attendants. The barbarians, positioned on both sides of this narrow pass, were clearly in a position to do harm at any time.

Instead of leaving by the way he had come, he searched for a shorter route. As he was making his way to Beroe by descending into the valleys, he lost the greater part of his army, and were it not for the fact that the Lord was with him, he, too, would be dwelling in Hades."" In places the ground was so rough as to be almost impassable and to cross the moun- tain passes he had to squeeze his troops through holes and defiles where a mountain stream flowed. The vanguard was led by the protostrator Manuel Kamytzes and Isaakios Komnenos, the son-in-law of the future emperor Alexios; the Sebastokrator John Doukas, the emperor's paternal uncle, commanded the rear guard. Emperor Isaakios and his brother, the sebastokrator Alexios, were in charge of the main body in the center which was preceded by the pack animals and followed by the camp attendants. The barbarians, positioned on both sides of this narrow pass, were clearly in a position to do harm at any time.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints