One of the largest cities in the world

One of the largest cities in the world

In the middle of the twelfth century Constantinople the population of the city was 400,000 or more. The city still had the appearance of a late Roman metropolis with public forums, shopping streets and apartment blocks. Even with this population there were still large tracks within the walls that were given over to farming. The population had not been this big since Justinian's time when plague wiped out two-thirds of the population in just three months time. The growth in population was due to expanding economic activity, increasing wealth, and immigration from Asia Minor - as people fled the advancing Turks. Much of the wealth of the Byzantine Empire was now generated by Constantinople itself, a huge consumer market created by the surrounding businesses, farms and fisheries that supplied its residents. This trade focused entirely on the day-to-day need to house, cloth and feed almost half a million souls and the taxes, rents and fees it generated financed the Imperial court. One thing that set Constantinople apart were her luxury industries, like the manufacture of fabrics, gold-working, glass, perfumes, books, furniture and works of art. The export of many luxury products was restricted to the aristocracy. The Imperial court was always the number one consumer of them. In earlier times the throne supplied court officials with their uniforms, a practice that ended in the 11th century. Court officials were paid enough to buy their own clothes and there was a big supply at reasonable prices on the open market. While luxury trades focused on the rich and elites of Constantinople, every home had its own - if more humble - furnishings. The middle-class market was huge, even for art. Every Christian household would have proudly owned and piously displayed at least one icon. These domestic icons were inexpensive; one icon was equal to the cost of a good pan. People placed them over the doors of their houses for protection and in thanks for the services that a saint had already provided. They gave icons as gifts for all occasions. Neighborhoods had a special attachments to icons in their local churches and had copies at home. This connected the home spiritually to the original icon and its saint. The glinting gold and bright colors of icons would have given their owners a bit of luxury and beauty, no matter how poor they might be.

A living history and art museum

A living history and art museum

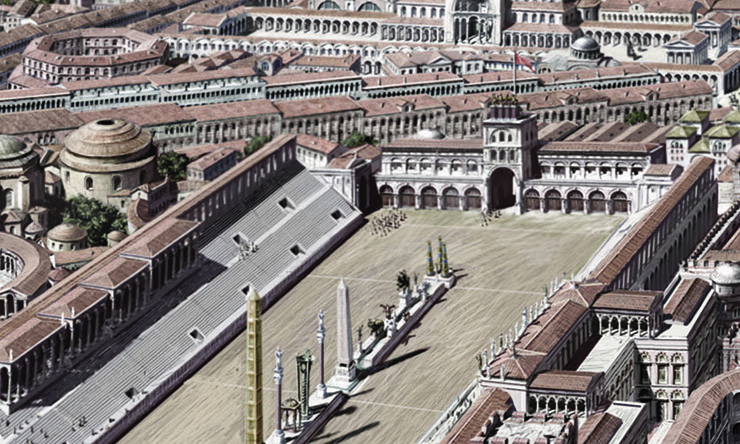

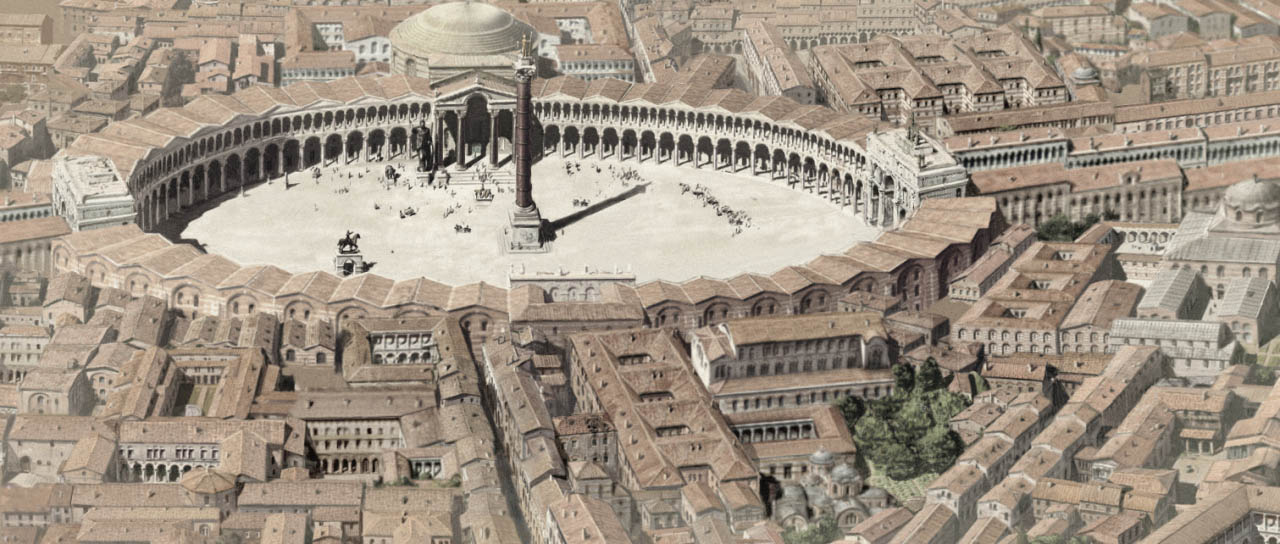

Beyond icons, the common people had an appreciation for non-religious art, since they were surrounded by secular works from ancient Greece and Rome in the city's forums, squares, colonnaded streets and the famous Hippodrome. The statues in the city were masterpieces by the most famous artists of antiquity that had been gathered up and brought to the city by Constantine and his immediate successors. As the Roman world became Christian temples were closed. Their cult statues of Zeus, Hera and Aphrodite came to Constantinople where they were put on public view. There were hundreds of churches and chapels crammed with beautiful things that people saw everyday. With so much to see in every quarter of the city, people took them for granted, although they could be very superstitious about this statue or that column, giving them supernatural powers over the fate of the city. The educated citizens of Constantinople cared about their history and the many famous and beautiful things to be found there. The Hippodrome was lined with dozens of statues, columns and other things the common people saw when they were at the races or games in the stadium. Sitting in the stands and crunching on snacks they would discuss the myths associated with the statues of men, beasts and giant insects which were placed along the spina - which ran down the center of the race track. No matter what your level of education or how rich you were Byzantines had an appreciation for art and beautiful things. They were also great followers of sport, fashion and stars of the theater.

The city of Constantinople was said to have been built on seven hills, just like ancient Rome. Many of the most important monuments were built along the high spine of the city and could be seen from just about everywhere. Byzantium was dominated by great columns which towered above the city that were crowned by statues and crosses. Some of these marble columns were wrapped in spiraling bands of sculpture glorifying the achievements of emperors. The column of Justinian was built by him right outside Hagia Sophia. It was as tall as the great dome and was crowned by a giant gilded statue of the emperor facing east in military gear on horseback. The tradition of erecting columns continued into 13th century. The Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus set up a column with a bronze statue of himself offering a model of the city to the Archangel Michael outside of the Church of the Holy Apostles. Soon after its erection the statue fell from the column in n earthquake and it was put back on its column by his son, Andronikos II. We don't know if it was a new creation or assembled from bits of other statues.

Life in the BIG city

Life in the BIG city

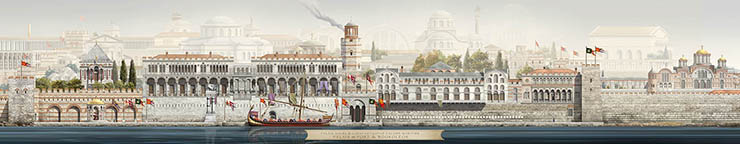

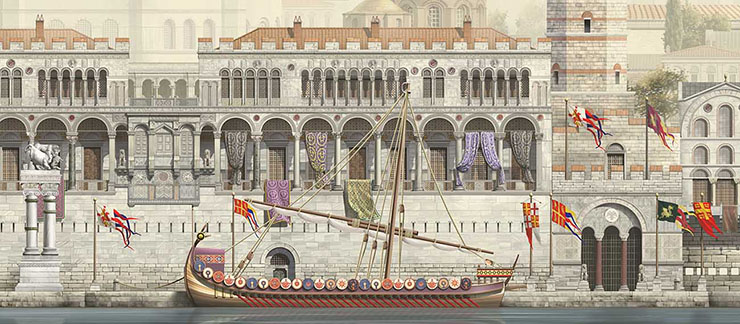

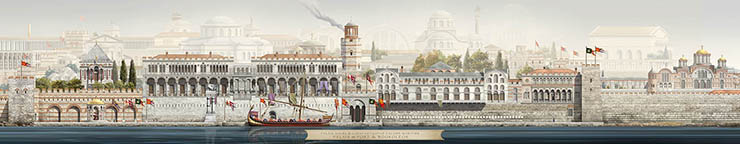

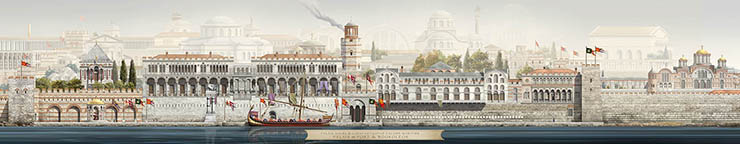

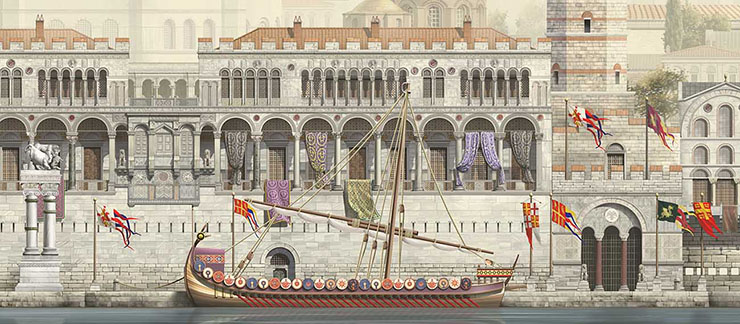

We can't loose sight of how filthy and over-populated parts of Constantinople were in the late 12th century. The population density varied greatly from neighborhood to neighborhood, there were still large areas given over to gardens and even small scale farming within the walls Constantinople looked like a fairy tale kingdom if you approached the city from the sea. The city was built upon a series of hills, and the horizon was dotted with domes colonnades and gilded monuments. There was a towering marble palace that had been built into the seawall, covered with balconies set with statues of marble beasts. It was called the Boukoleon Palace and it had its own a marble quay and private harbor to welcome guests. Towering above everything was a mammoth column crowned with a gilded statue of Justinian on horseback facing east. Next to it was the enormous Church of Hagia Sophia, justly world famous for its size and beauty. Throughout the city there were the splendid stone mansions of the rich which boasted paintings, mosaics, luxurious furnishings and walls of precious marble revetment. However, once you entered the city the city you would discover a shocking juxtaposition of wealth and poverty to be seen everywhere, even in the most desirable of neighborhoods. The rich and poor lived right next to one another.

Most private homes in Constantinople were courtyard homes. There would be communal big dome ovens in them for cooking - especially the making of bread. These ovens required wood which was delivered directly to homes and building by commercial companies. Different kinds of wood and charcoal were used for various purposes. There were portable braziers kept on upper floor for warmth and to prepare small meals. As a highly developed urban society Byzantine homes had a wide variety of pots and utensils used in the preparation, storage and eating of food. Homes also had large tanks for water storage in their courtyards and smaller ones in homes.

Water was brought to your door in wooden tanks on carts for sale or extracted from wells. Many homes had direct access to cisterns - there were thousands of them all over the city. Homes in Constantinople had evolved from Roman style apartment buildings and courtyard houses. You could find fine nobles living in palaces -- right next door to five-story tenements of incredible squalor. The smell at ground level would have been dreadful, all of the sanitary facilities were on the ground floor. When more people were added to a building there was no way to add more toilets. Wealthier people lived on the top floors, but they still had to climb down to the ground floor to use them - or use chamber pots emptied by others. As more people moved to the city landlords built up - adding floors to existing buildings and dividing up great houses. Not a wise move when the additions were often constructed of wood and the streets were so narrow. Fires were frequent and an indicator of the decline in the quality of life as the city became more crowded. Before 1204 most of the private homes were built of stone and brick, in late Byzantine times - and throughout the Ottoman period - homes were built mostly in wood. The fires set by the Crusaders of the Fourth Crusade did more damage to the fabric of city than pillage. Vast areas were reduced to ashes and the fires marked the true end of the ancient city as its porticoes, shops and forums were destroyed. The fires came very, very close to Hagia Sophia and reached the edge of the atrium.

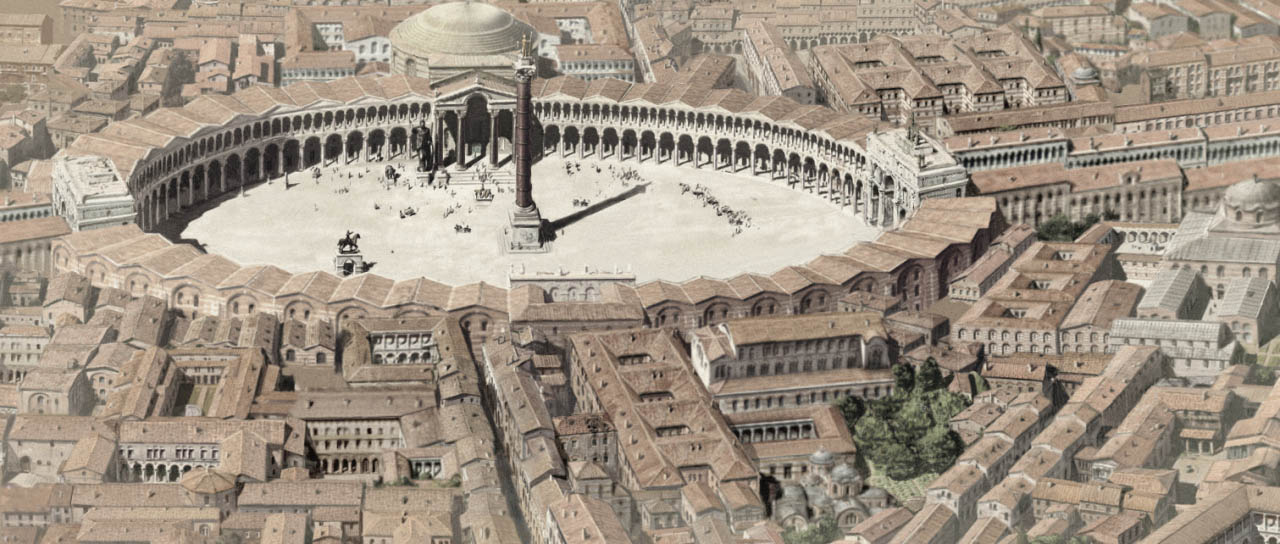

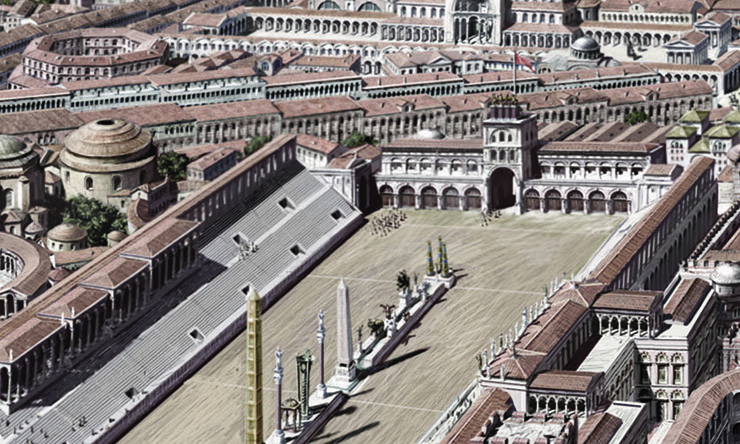

The image above is of the Forum of Constantine. In the center is his red Porphyry column topped with his statue. Here you can see the Roman-style apartment blocks and courtyard homes.

The image above is of the Forum of Constantine. In the center is his red Porphyry column topped with his statue. Here you can see the Roman-style apartment blocks and courtyard homes.

A city built of wooden houses

Outside of the public buildings and churches, the city in the 12th century was mostly built of wood. Even the brick and stone shops in the forum had wooden roof beams. They were imported from the great forests of the Pontic mountains facing the Black Sea. The forest stretched all the way from Georgia to the Sea of Marmora and the Black Sea coast of Bulgaria. There were vast supplies of Nordmann Fir that could grow to 255 ft tall. It was soft, white and easy to work. It came in very long planks and was perfect for private homes, the beams of basilicas and scaffolds, too. There were lots of other woods to be harvested, Oriental Beech, Sweet Chestnut, Black Alder and Scotch Pine among them. There were many types of wood used in the building of homes and furnishing them.

The city had many skilled craftspeople who were woodworkers. Carpenters roamed the streets and forums carrying their tools of the trade on their backs, like big two-handled saws, looking for work from door to door. You could order chairs, chests, doors or beds right from them. The cost of furniture was cheap. The largest expense was often the wood. Carpenters made furniture without nails using elaborate mortising and joinery. Furniture was ornately carved and ornamented with inlays, turned spindles and friezes of leaves and flowers. Some pieces were then gilded and painted in bright colors. Amazingly, some furniture from Byzantine times has survived so we can appreciate the craftsmanship of the carpenters who made it and the beauty of the designs. Furniture was also sold through shops.

The main problem with the lumber used in large scale construction, like Nordmann Fir, was how easy it was to burn. To prevent its flammability the sap was removed during processing of its logs. One of the reasons the city was so quickly rebuilt after fires was the availability of cheap lumber in inexhaustible quantities that could be delivered in a few days.

Pontic wood was also used in shipbuilding. Constantinople had thousands of ships of all sizes supplying its needs in port every day. It has been calculated that at least 500 ships would have been needed to supply the grain for the city's daily bread requirements.

Pontic wood was also used in shipbuilding. Constantinople had thousands of ships of all sizes supplying its needs in port every day. It has been calculated that at least 500 ships would have been needed to supply the grain for the city's daily bread requirements.

Taverns and bars

There were hundreds of taverns and wine bars in Constantinople all over the city. As today, location was very important to a tavern's success and one could find big ones in business districts near the Golden Horn. Being an innkeeper could be a very profitable business. There are business records of their resale that tell us how much they sold for along with their location, descriptions of the type of business they were in and how popular they were. Taverns served food as well as wine and could be operated by men or women. They were often run by families. One tavern, owned by Goudeles, was situated outside the city wall on the Golden Horn, proudly advertised that they served the finest Cretan wines, like malvasa. There seem to have been chains of taverns that were operated by importers and wholesalers of wine. The Venetians operated too many taverns and were forced by treaty to reduce their number to 14. This did not satisfy the city authorities who proceeded to tax them out of existence. They were more profitable because they were exempted from paying taxes as a result of their trade treaties with the empire. These exceptions were resented by native operators of taverns and their patrons. As a result Venetian merchants were the target of riots, they were driven from the city and their businesses confiscated on more than one occasion. The loss of revenue from their taverns in Constantinople was so significant that the resident Venetian official who oversaw their operation could not be paid his salary of 1,000 ducats a year.

Favorite Wines and Foods

The citizens of Constantinople were sophisticated consumers of wine of all kinds. Grapes were grown on low stakes and as rampant vines and in trees. The best wines came from nearby Bithynian Bursa, Cyzikus and Nicaea. The finest Bithynian wine was the white theraia ampelos grape, sweet and thick like honey. It came in three grades with the finest being reserved for the Imperial court. The rarest wines were created in small batches and came in small amphora, they were described as being "fit for a king". Cheaper wines were described as watery. Sweetness was what made a wine more desirable. in 1307 the Ottoman Sultan Osman ordered the destruction of the Bithynian vineyards in order to drive all of the Christian farmers from the land. The Turks were nomadic herders, not settled farmers. This created the first-ever shortage of wine in Constantinople. It also increased the cost of wine and the value of vineyards. Another result was the migration of wine production to coastal producers and the shores of the Sea of Marmora. Soon after the Turkish conquest of Asia Minor they became passionate consumers of Bithynian wines themselves, which could only be grown by Christians.

The citizens of Constantinople were sophisticated consumers of wine of all kinds. Grapes were grown on low stakes and as rampant vines and in trees. The best wines came from nearby Bithynian Bursa, Cyzikus and Nicaea. The finest Bithynian wine was the white theraia ampelos grape, sweet and thick like honey. It came in three grades with the finest being reserved for the Imperial court. The rarest wines were created in small batches and came in small amphora, they were described as being "fit for a king". Cheaper wines were described as watery. Sweetness was what made a wine more desirable. in 1307 the Ottoman Sultan Osman ordered the destruction of the Bithynian vineyards in order to drive all of the Christian farmers from the land. The Turks were nomadic herders, not settled farmers. This created the first-ever shortage of wine in Constantinople. It also increased the cost of wine and the value of vineyards. Another result was the migration of wine production to coastal producers and the shores of the Sea of Marmora. Soon after the Turkish conquest of Asia Minor they became passionate consumers of Bithynian wines themselves, which could only be grown by Christians.

The Byzantines ate very well, food was cheap and plentiful. They loved cheese and imported a lot of it from Crete. The Venetians got control of the market created a monopoly on the supply. In the 12th century the Venetian Quarter of the city is recommended for the best cheese. People ate lots of fish, shellfish. mussels and calamari - all cooked in oil and heavily spiced. Fish came from the thousands of boats that supplied the city with goods on a daily basis. Seafood was delivered from the Sea of Marmara to the south side of the city and then brought into the city by middlemen who bought the catch dockside. The docks were controlled by great commercial ventures, mostly churches and monasteries of the city. Unlike meat, there was no central marketplace for fish, you could buy it anywhere in the city.

Besides fish people ate lots of bread. The main bread market was located between the Forum of Constantine and the Forum of Theodosis, which may have focused on the main ingredients of bread, since you could buy the finished product all over the city. Dinner was often just wine and bread. Lunch was the principle meal of the day. Sausage was another source of protein that was widely produced on small farms. Partridges, pigeons, blackbirds and goose were also commonly eaten. Enormous geese were stuffed with all sorts of herbs and small game birds at feasts.

Eating at home

At home people in the 12th century ate meals communally - they used their hands to serve themselves from large, rimmed platters and footed bowls. In Comnenian times fine white-glazed ceramics were produced in vast quantities, were inexpensive and came in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Some were plain and others were highly decorated with animals, loving couples and geometric shapes. Knives and forks were used increasingly throughout the century. Tables were tall, square, and covered with white linen table cloths. Everyone used linen napkins, which were folded and embroidered. The napkin was held in the right hand while dining. Lots of bread was provided - the Byzantines ate huge amounts of it, and they were developing new types for the table, including bread made into pretzel shapes. Wine was served on trays of glass bottles and large glass goblets. At the table they were refilled directly from small amphora and large flask-like bottles by servants. Sophisticated banquets served multiple main and side dishes and throughout the 12th century there is an increase in the serving of rare and exotic dishes. Truffles were considered a great delicacy, a food suited for princes. that was an expensive present. Caviar was widely popular. Just like today the most treasured was sturgeon caviar from Russia, the Black Sea and the Caspian. Salt-cured fish eggs were very common and inexpensive.

More on Byzantine cuisine - what they ate

Vegetables were fresh and dried. Fresh fruits and nuts were locally supplied from gardens in the city and other operated just outside the walls. People also ate lots of dried fruit which was shipped into Constantinople from exotic places. Raisins came from Syria and the Peloponnesus. Dried figs also came from the Peloponnesus and were imported in vast quantities. Sweet fruits like figs were preserved in honey and sold in glass containers sealed with wax in Constantinople. Apples, quinces and citrus were also cooked in honey and combined with spices. Naples was the source for the large scale importation of chestnuts, hazelnuts, walnuts, as well as almonds in shell, shelled or crushed. Nearby Bulgaria also produced honey and candle wax for the city. It was also produced locally in and around Constantinople, where it was produced on farms and in monasteries. There were many hives in the city. A single producer could easily manage 150 hives or more. It's interesting that monks were encouraged to eat as much honey as they could find in the wild or produce in the monastery. Honey was considered a gift from God. Sugar was a luxury item that came from Syria and Cyprus and does not seem to have been used much. Fried foods were easily produced at home, but a large amount of food was sold by street peddlers and roadside kiosks, largely operated by women.

An important factor in what people ate was the religious calendar which regulated what Christians could eat and when.

The wine trade and olive oil

The wine trade and olive oil

Wine was supplied by private enterprises and monasteries. It came from all over Greece, Italy, Crete and Asia Minor and was transported in clay amphorae - just like in ancient times - until the 14th century when wine barrels became the norm. The shift to barrels strained the Cretan wine industry because they quickly ran out of wood and had to import barrels from abroad. Wine and its transportation was a big business in Byzantium and very profitable. A single ship carrying 20,000 amphora each holding 7-8 liters of wine - 140,000 to 160,000 liters - was shipwrecked on its way to Constantinople in the Sea of Marmora in the 11th century. This means each amphora contained the modern equivalent of 5 bottles of wine and a huge shipment like this one could serve around 50,000 people for just one day. A large quantity of red wine was exported from Southern Italy to the city. It was popular for its high level of alcohol which also made it easier to ship and store. There as a market for rare and exotic wines. The imperial court was a customer for them. We have records showing wines that were shipped to specific emperors. Amphora often carried the mark of their wine's origin.

The city consumed lots of olive oil and this came increasingly from growers in Greece where production expanded greatly during this time period. Olive oil came primarily from a narrow band of producers around the Aegean Sea. Ships would annually visit local ports and buy up and ship their access production to Constantinople. Olive oil was used both for cooking and also for lighting.

Flowers and plants at home

In spring and summer the city was covered with flowering vines, roses and fruit trees. Late May and the first week of June was the height of fragrant rose production, which were used to decorate rooms, streets, palaces and churches - and to produce rosewater. Where ever there was a space or a pot to plant something in people did. They filled their windows and balconies with beans, peas and flowers. If they living in a house with a flat roof the inhabitants would plant anything they could that could be harvested and eaten. People who were fortunate enough to live in a house with a courtyard could plant fruit trees, grape vines and even roses. In summer all of this greenery could have made life in the city more fragrant and pleasant. Home-grown flowers and herbs were the primary source for the fragrant essences women used in cosmetics and to scent their clothes or create sachets. Christians were encouraged to adorn beds with flowers like roses. Rosemary, which was easy to grow at home, was added to soap. It was also scattered on floors to freshen up rooms. People burned aromatic woods and incense in their homes to freshen the atmosphere. Fragrant unguents were added to the oil in lamps to perfume homes. Visitors were always anointed with rosewater to welcome them to your home.

Lots of events & celebrations in the Hippodrome - Popular Sports

The city had a full calendar of events, both secular and religious. Some of the annual religious holidays associated with specific saints had devolved into excuses for drunkeness, ribaldry and licentiousness. There were processions through the city continuously filling the streets and forums with scent, music, color and ceremony. There was gambling on professional sporting events like chariot racing. A marble gambling machine has survived where money was wagered on the outcome of the chariot races; here colored balls would be rolled down the tracks and through the holes, with gamblers placing bets on which ball would emerge first at the back. A Byzantine churchman complained about the obsessions of the fans of chariot racing:

"There are those who are in a state of excited distraction over the spectacle of horse racing and are able to state with complete accuracy the names, the herd, the pedigree, the place of origin, and the rearing of the horses, as well as their age, their performance on the track, which horse drawn up against which other horse will be victorious, which horse will begin best from which starting-gate, and which charioteer will be victorious over the course and outrun the opposition"

The people were mad about chariot racing. Drivers of the chariots had big fan bases and were dressed in splendid uniforms in bright colors so you could easily spot your favorites. White horses were much admired and fans followed horses in their stables, studying them to ascertain winners. Betting on horses was widespread. Drivers could come from any class, even Imperial princes and emperors drove chariots in races. One emperor, Michael III, acted as godfather to the children of his favorite charioteers and gave gifts of 50 to 100 lbs of gold for each of their children. He promoted his coarse chariot-driving buddies to the ranks of patricians. One of Michael's favorite drivers was named Himerios, which means "Most Longer For" in Greek, was nicknamed "Pig" because he was ugly. Michael gave Pig 100 lbs of gold. This scandalized the court because he invited Himerios to formal dinners were he demonstrated disgusting habits in front of everyone and used gutter language.

Michael melted down the famous golden trees with singing birds, the beaten-gold lions and griffins of the throne, and golden organ that so impressed visitors to the Imperial palace to cover his sporting expenses. Even then he was unable to make the annual payroll of the court or pay any of the bonuses they expected.

The Emperor Alexander, whose portrait can be seen in the North Gallery of Hagia Sophia, took tapestries and silver candelabra from the churches of the city to decorate the Imperial box during races. He was also a fan and daring - even reckless - participant in polo matches. He played a match while drunk and died afterwards.

Drivers could be very young - just boys with their first beard. The bellows of pipe-organs were set at the turning point of the Hippodrome and roared out as the chariots went by. You could hear the roar of the crown within the walls of the Hippodrome which magnified the din. It is hard to imagine this in the 12th century. Constantinople was the only place in the world where chariot races still took place. The Crusader princes and kings who passed through Constantinople were offered races as part of the spectacle of life in the city. One can only imagine what they thought of Constantinople and daily life of the people. The last chariot race in Constantinople we know of took place in 1200 and was held in the huge courtyard of the Blachernae Palace during the celebration of an imperial wedding. There were other race tracks in the city, including one within the walls of the Great Palace.

Polo was another popular sport in Constantinople, which was played by mounted military officers and Imperial princes. It was very dangerous and often resulted in death. There was an Imperial polo field within the Great Place and others to the west, outside the walls of the city.

The Hippodrome was still the location of games, wild beast fights and public assembly. Women attended all of the events.

Every year the city celebrated carnival when its residents dressed in outlandish costumes, wore masks and danced in the streets. There were acrobats, animal acts, dancers, singers, burlesque pantomimes, group chants and organized cheers for the emperor - all backed by musical instruments like harps, guitars, zithers, trumpets, clarinets, drums and water organs. There were even giant bears that played musical instruments. Just like today musicians played in the streets for tips and could be hired or employed in places like taverns to attract business. Trumpets, kettle drums and clarinets could be very loud and were played out of doors while stringed instruments were used for intimate occasions.

Al-Marwazi, the Arab physician who visited Constantinople in the early twelfth century, saw concerts,wrestling matches, and races, all in the presence of the emperor (Manuel I) and empress in the Hippodrome, he says:

"They set dogs upon foxes, then cheetahs upon antelopes, then lions upon bulls, while (the onlookers) feast and drink and dance.” In addition the Jewish world traveler Benjamin of Tudela visited the Hippodrome on Christmas day and reported “men from all the races of the world come before the king (Manuel I) and queen with jugglery and without jugglery, and they introduce lions, leopards, bears and wild asses, and they engage them in combat with each other; and the same thing is done with birds. No entertainment like this can be found in any other land.”

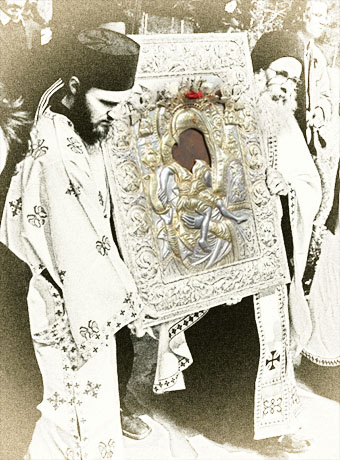

From time to time emperors would celebrate military victories by public triumphs through streets lined with tapestries and hung with garlands of flowers. The streets were also strewn with fragrant herbs like rosemary and myrtle, grape leaves and flowers. The most celebrated procession in the city was the weekly move of the Hodegetria icon of the Theotokos from its monastery in the area of the Great Palace along the main street of the city, the Mese. It it stayed for short periods of time in various churches along the route before returning home. The icon was conveyed by a guild of men dressed with wings - like angels - and wearing red silk uniforms.

Augusteon & Antechamber of Hagia Sophia - Archangel Michael Chapel

At Easter the great square in front of Hagia Sophia - the former Augusteon which the Byzantines later called the Agora - was full of wooden stalls selling food, drink, icons and other crafts. The Augusteon was a location of restaurants and hostels serving locals and pilgrims. It had many columns and statues including the towering Column of Justinian, mentioned earlier, which soared above the roof of Hagia Sophia and bore a gigantic bronze statue of the emperor on horseback facing east. There were many lofty churches and chapels surrounding the Augusteon, you could look into the square from their roofs and watch the people milling about. The primary entrance was a great triumphal gate of marble called the Milion. The Augusteon had locked gates and was packed between 6 and 9AM. There was a local tradition of having breakfast here after the morning service in Hagia Sophia. The emperor and the Imperial family would use their own private restaurant in the nearby Great Palace.

On Sundays it was traditional for people to also bathe after attending liturgy. There were public baths built nearby, and an Imperial one for the rulers and their families. People brought their own towels.

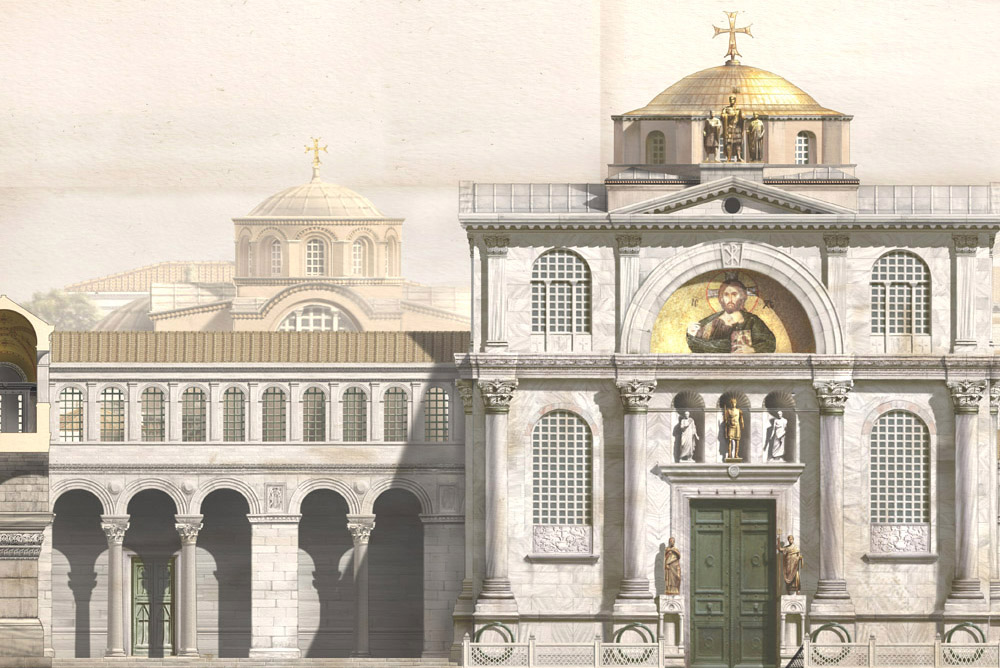

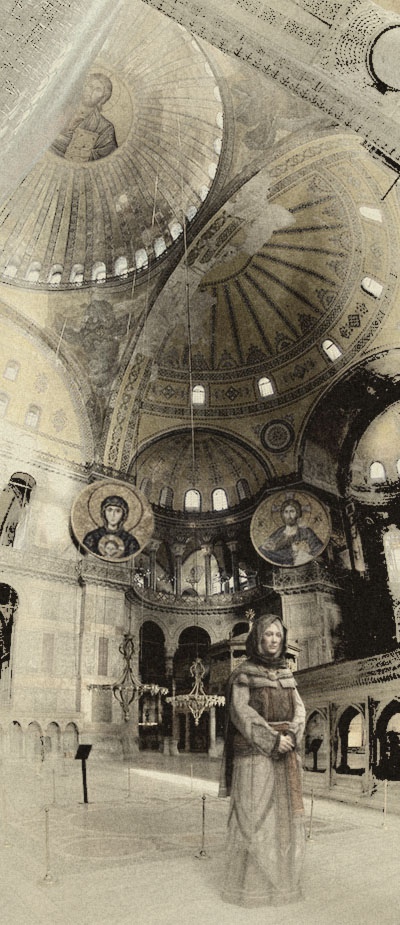

You would enter Hagia Sophia through the Antechamber-Chapel of the Archangel Michael, which was adorned with a beautiful mosaic of the head of the angelic host holding a sword. The entrance to the church was locked at night. The entrance through the South Vestibule was rather narrow and dangerous if too many people tried to enter the church at one time, especially if a uncontrollable mob was involved.

There were still many theaters in the city which hosted performances of plays and pantomimes, incorporating dancing and music. Some of the theaters were late-antique marble buildings while others were wooden shanties that doubled as taverns with in-house entertainment. In Byzantium women were actresses and singers, there were no prohibitions against them.

Byzantine dress and jewelry

Clothes were mostly professionally made and sold either through shops or through street peddlers who bough and sold both new and used clothes. Professional tailor shops, regulated by the city prefect, controlled the supply of thread and fabric. Clothes were made in pre-made batches by cloth, color and style. Individual tailoring was done at the point of sale to fit the customer. Most day-to-day clothes were made of wool. Linen was also extensively used for clothes, towels, sheets, curtains and under-garments. It came in many levels of quality and whiteness. There was a high-status production of fine linen that was embroidered in silk or even gold thread. Linen was grown outside the city and processed as thread or cloth before it was brought to Constantinople. Dying cloth was a dreadful and smelly business that was often done by Jewish workers. Dye colors could be extremely expensive and many were difficult to apply. Multiple dyings were often required to get the right hue or intensity of color. It was easy to ruin fabric during the dying process. Silk was a prestige material for clothes that became widely available to the consumer market in the 12th century in lower quality thread and in combination with other fibers, like linen. Silk was also produced with recycled thread from old clothes. The local market in Constantinople became so large that it could no longer satisfy local production. Jewish families created new silk weaving workshops outside Constantinople in cities like Thebes and Corinth in Greece. Silk worms were grown there so it was close to the source of production. It was also outside he control of the city prefect who controlled production in and around the city. Silk worms grew on mulberry leaves from groves of trees in Greece (the medieval name for Greece, Moreos or Morea, means Mulberry tree) and the cocoons were processed there. Local production would have also included dying of the thread or woven cloth. Once it was completed the product was easy to export - east or west - by ship.

People stored their clothes in flowers, herbs and perfumed essences which kept them fresh.

There was a big market in clothes - both and used - at the annual festival in honor of St. Demetrius in Thessalonica, where there were more that a thousand booths in big rows selling them. People came to buy and sell at the fair from all over the world. Your personal purchases could be tailored on the spot or bulk purchases could be bundled and shipped by land or sea right from there. Most of Greece, both villages and towns, was probably supplied with clothes from the annual fair.

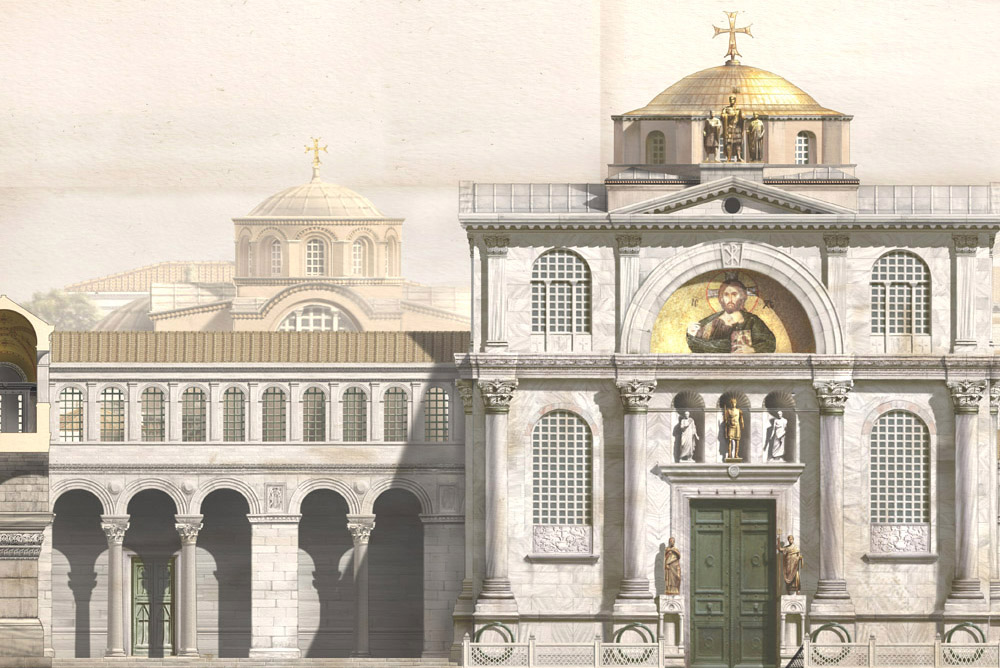

Above is a wonderful reconstruction of the Chalke - Bronze - Gate to the Great Palace Above the door on the right is the famous mosaic icon of Christ. The Chalke Gate was decorated with bronze and marble sculptures and had huge bronze doors. On the left is the famous elevated passage that led from the Great Palace to the South Gallery of Hagia Sophia. This passage was built by Justinian and was used by the Imperial court. Behind it is the Church of Christ Chalkes, rebuilt by John I Tzimiskes (969-976) in the late 10th century. He was buried there after a very short reign.

Above is a wonderful reconstruction of the Chalke - Bronze - Gate to the Great Palace Above the door on the right is the famous mosaic icon of Christ. The Chalke Gate was decorated with bronze and marble sculptures and had huge bronze doors. On the left is the famous elevated passage that led from the Great Palace to the South Gallery of Hagia Sophia. This passage was built by Justinian and was used by the Imperial court. Behind it is the Church of Christ Chalkes, rebuilt by John I Tzimiskes (969-976) in the late 10th century. He was buried there after a very short reign.

Styles of clothes changed rapidly during this time and were influenced by foreign styles of dress. There was even something of a youth fashion market in Constantinople. It was male-dominated because men lived their lives in public while most women's lives were defined by church and home where modesty and practicality was valued. Women dressed for comfort. Manuel I had no problem with foreign dress, he wore Latin clothes himself on occasion. Manuel was such a fan of Latin things that he competed in military jousting when he was in Antioch. His father, John II, had been concerned about the wearing of new fashions of grooming and dress at court and made his family conform to his tastes. This did not extend to foreign styles of military clothes - like tightly tailored silk kaftans - which he himself wore. For generations Emperors had given gifts of these silk kaftans to other men. Alexius I, Manuel's grandfather, gave gifts of his own clothes to friends and foreign generals and rulers he knew.

Women wore more jewelry than men did. Men wore signet rings of rings decorated with saints and religious inscriptions. The most decorated part of a man's apparel was his belt, which could sport a gold or gilded buckle with other ornaments. Women wore rings, bracelets and earrings. Bracelets of glass where popular at this time and many have been found. Earrings were often the most expensive pieces of jewelry a woman owned and could be very valuable heirlooms. While the most precious earrings were made of gold, pearls and gemstones, the common people wore earrings of gilded or silvered bronze set with small pearls and glass gemstones. Both men and women wore crosses and reliquaries around their necks. They were not worn on top of ones clothes, but underneath, next to the body. Thousands of examples have survived because they were generally made of bronze rather than gold. Of course the rich and powerful could wear very expensive jewelry. Only the Imperial family wore crowns. Men and women of all classes carried small purses for coins on their belts.

The life of women in Constantinople

Anna Comnena says that women veiled themselves when they went outside the home, but this certainly did not pertain to working women. One cannot imagine women running businesses and doing physically demanding jobs while being veiled. Adult women wrapped their braided hair and heads with turbans, which could be simple or used beautiful silks with tassels, knots and fringes following the current fashion. In the 12th century women wore a cylinder head wrap that had been sewn together that was easy to put on and take off. Working women in workshops, retail stores and in the fields would have wore what ever was practical based on the job. In church it was considered proper for women to wear a veil over her turban. An Arab traveler to Constantinople remarked that all of the shops of the city were manned and run by beautiful women. Many of the street peddlers and people selling foods and drink were women, too. There is a manuscript showing female silk weavers working inside with their heads covered. Another manuscript shows a silk merchant named Danilis wearing a loosely draped silk veils around her head and shoulders on a visit to the emperor. Her face is uncovered.

There was an annual female festival called Agathe on May 12th and had been organized around the birthday of Constantinople which was celebrated on May 11th, the previous day, in the Forum of Constantine and the Hippodrome. The woman's festival began with a great procession through the streets of the city by thousands of women who were involved in the craft of cloth making, spinners, weavers and carders of wool. We can be sure that the women would have worn the beautiful clothes and hats they had made themselves. It was a festival of professionals led by the older women who were recognized as the experts in their craft. The festival had organized activities of ritual and ceremony. The goal of the procession was a church where there were displays of the art of cloth-making and then the women made offerings of their best work to the church. After finishing at the church the women gathered for the singing of songs and engaged in group dancing accompanied by musicians.

Women washed their hair in special fragranced solutions that naturally lightened it, including saffron, turmeric, fern roots and citrin-colored sandalwood and rhubarb. The cloths they wrapped their hair in were usually brushed with perfume. People made their own scents at home. Lotions and creams were made fresh from natural sources and had to be used in a few days.

Spotting foreigners

You could recognize a person's nationality by the clothes they wore. Bulgarians were often pointed out for their outlandish clothes. You had to be careful wearing foreign clothes in Byzantium. It could be dangerous. People were killed by soldiers or police who mistook them for the nationality of the clothes they had on. Hats were also very popular and came in many styles. Dress was regulated by the government for professions or guilds - thousands of these uniforms were produced in silk annually and were the staple production for some firms who had government contracts to produce them. They were worn during group processions and stored by the government when not needed. They were kept in storerooms in the Great Palace. Maintaining and repairing them was an ongoing concern of the government workers attached to them.

Brothels and prostitutes

Constantinople had many brothels - the most famous were located in side streets near the Forum of Constantine. Foreign visitors were shocked by the vice they saw in the streets, especially the prostitutes who openly worked the streets. The Crusaders expressed dismay at them and then patronized them. The city regulated prostitution under the city prefect and they were taxed. Like Paris in the 19th century Constantinople had many famous courtesans who were sometimes also actresses and dancers in the public theaters. One can assume women also worked independently as sex workers throughout the city. They also worked privately in the neighborhoods of the city, living in shacks right alongside churches. One account says they could be very noisy - you could hear them in the local church during services - which indicates drinking was probably going on there, too. The church seems to have ignored the trade.

Bathing and the water supply

Bathing and the water supply

The water supply of the city was under stress because of the increase in population. The imperial administration was concerned about finding new sources to bring into the city and improving the supply from established aqueducts. The problem was not only finding new sources but how to get water into the center of the city. People were encouraged to open up old cisterns and make new ones. The water system seems to have been remarkably free of water borne diseases. Very deep cisterns were especially trusted as a source for street vendors of water. I had never read about outbreaks of typhoid in the city, but there are many accounts of outbreaks during military campaigns. The city seems to have done a good job in managing the drainage system.

There were many public baths; the Byzantines - even monks and nuns - bathed frequently. One was expected to bathe twice a week. One of these baths is still in operation Istanbul today. Clothes were cleaned at home or in commercial operations. Home cleaning could be communal by building or neighborhood involving boiling them in great tubs of water and soap. The Byzantines had a wide variety of cleaning products for bodies and clothes.

Safe behind the city walls?

People felt safe within the walls of Constantinople. However, the French Crusader, Odo of Deuil, who visited Constantinople for 23 days in 1147 with the French King, Louis VII and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, reports:

"The third side of the city's triangle includes fields, but it is fortified by towers and a double wall which extends for about two miles from the sea to the palace. This wall is not very strong, and it possesses no lofty towers; but the city puts its trust, I think, in the size of its population and the long period of peace it has enjoyed. Below the walls lies open land, cultivated by plough and hoe, which contains gardens that furnish the citizens all kinds of vegetables. From the outside underground conduits flow in, bringing the city an abundance of sweet water... The bishop of Langres, however, urged us to take the city. He proved that that the walls, a great part of which collapsed before our eyes, were weak... He added further that Constantinople is Christian in name, not in fact."

In just a few years the crusaders would take the city in the Fourth Crusade scaling the walls in this very spot.

Doctors and Hospitals

Constantinople had a large number of highly trained doctors. For example the church of Saint George of Mangana had several free hospitals attached to it, one for the aged, another for the poor, a hospital for homeless migrants and a general hospital for everyone else. One reason Alexius I Comnenus was transferred to the Mangana in his last days, was because his doctors wanted him to be close to the hospital here. There was a pharmacy system in the city and workshops that produced medicines. In the 12th century Manuel I Comnenus himself created new drug compounds to be distributed throughout hospitals in the city, so we can see that hospitals had - for good or bad -the attention of emperors. The Emperor Theophilus established a hospital designed for the healthy exposure to gentle breezes and beautiful views for the benefit of the patients.

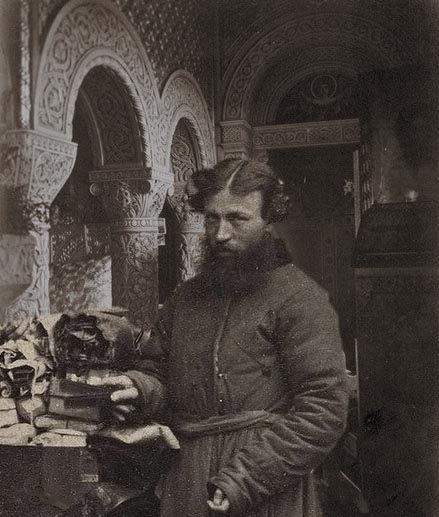

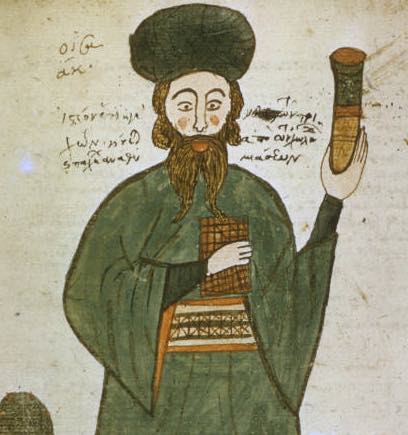

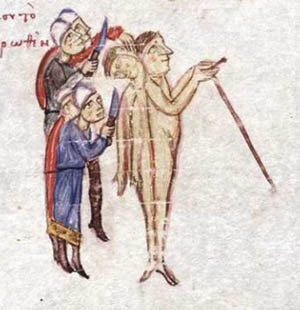

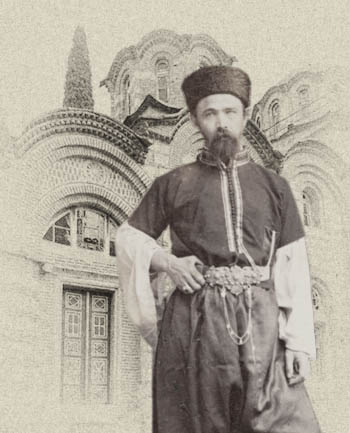

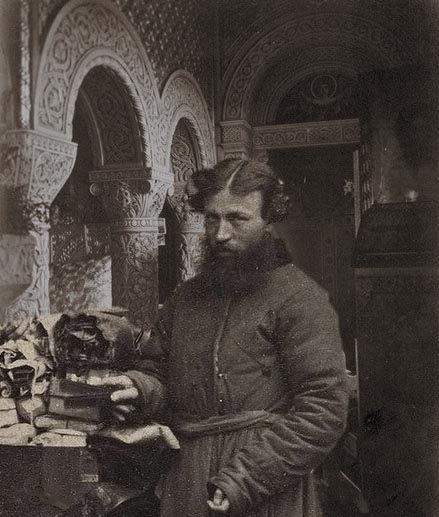

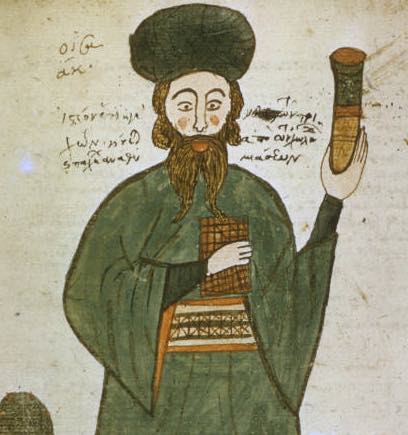

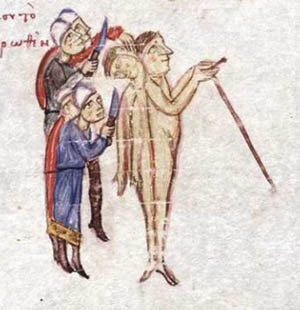

On the right you can see an image of a Byzantine doctor in his official uniform (notice the turban), he is holding medicine in a glass or metal vial. This is a portrait of a real man. He must have been very proud of his forked beard. Doctors would have carried medical handbooks like this.

On the right you can see an image of a Byzantine doctor in his official uniform (notice the turban), he is holding medicine in a glass or metal vial. This is a portrait of a real man. He must have been very proud of his forked beard. Doctors would have carried medical handbooks like this.

Byzantine hospitals were major business ventures, with specialized services and highly professional support staffs. In Constantinople the doctors ran the hospitals, which also had out-patient facilities. Hospitals operated in-house schools for the children of the doctors on staff. Doctors who worked in the hospitals also had their own private practices; they worked for six months in the hospital and the rest of year was free. Doctors were not paid for their work in the public hospitals and were discouraged from accepting tips. Women could be doctors, the famous Princess-Historian Anna Comnena was a doctor who ran her father's 10,000 patient hospital, which was the largest in Constantinople in the 12th century. Anna was a specialist in the treatment of gout. Hospitals had big support staffs. Beyond nurses and orderlies there were cooks, maids, errand boys and people who kept the medical instruments sharp and clean. Indeed, cleanliness was a great concern and there were many laundresses and people who operated water boilers. All of this went on until the end of the empire. We know the Mangana hospitals were still functioning in the mid-15th century.

Byzantine doctors performed dissections of corpses to study the internal organs of the human body. Unlike the Catholic west, the Orthodox church had no problem with this practice. Doctors in Constantinople were well known for their skill in the cleaning and dressing of wounds. I wonder what they used to prevent infection.

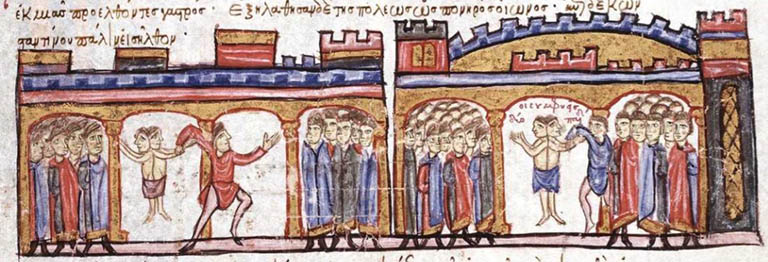

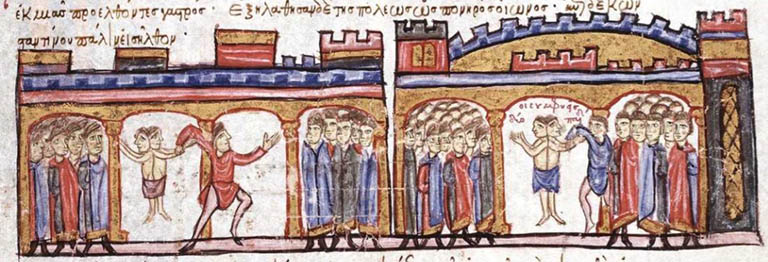

Doctors undertook some dramatic operations. There were a famous pair of Siamese twins from Armenia who were seen hobbling about the forums and streets of the city, walking with difficulty using a cane. Some people felt sorry for them and pitied their condition, but most thought they were a portent of great evil and they were driven from the city. They shared a belly. Returning to Constantinople in serious condition - one of the twins was dying - they were brought to a hospital in the city. A doctor there said they could separate them, one of the twins was near death anyway. He, along with a team of four doctors and assistants, operated on the twins. They were held down and no anesthetic was used! One of the twins - the one that was near death anyway - died after the pair was cut apart with large knives. That one lived, even for a short while - is an amazing fact. Who would have thought that a surgeon in the 10th century could perform such an operation without antibiotics. The incident was so famous it was recorded in the illustrated history of Skylitzes, you can see it below:

The twins are seen in the streets of Constantinople. A man drags them to a hospital.

The twins are seen in the streets of Constantinople. A man drags them to a hospital.

Doctors cutting the twins apart while the one on the left dies. His brother offers his walking stick in thanks to God for saving him.

People from foreign lands came to study medicine in Constantinople. The Norman Oto of Stigand came to the city with his brother Robert for three years and during his stay he became a doctor and veterinarian. In Byzantium human and animal doctoring were two different professions. The two brothers became fluent in Greek and served as commanders in the Imperial Guard. When they returned to Normandy (loaded with treasures including gold, jewels and the relics of St. Barbara) they intended to use their training to operate field hospitals for William, the Duke of Normandy, who invaded Britain.

Education of children

An educated guess would suggest a 30 per cent rate of basic literacy and numeracy among men in the Byzantine Empire, comparable to that in eighteenth-century China and superior to that in eighteenth-century France. This rate would have been higher in Constantinople, maybe as high as 50%.

Boys were educated until they were around 14 years old, girls until they were 12. Following Christian teaching in a perfect world children were seen as innocent and pure creatures, full of faith and not yet uncorrupted by the sins of adulthood. Most children were expected to follow in the footsteps of their families and work in the same professions or family businesses. Girls and boys generally married within their own social groups. Doctors and nurses are a good example of this, their kids were educated in their own schools and even lived close by one another. Girls were taught to read and write, while boys were also taught grammar, poetry, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and even music. Some girls were also educated in these other subjects if their parents wanted it. One can expect the children of professionals like doctors and nurses would have received as broad an education as possible. Language and grammar was taught through the study of the Bible and history. There were educational competitions at most schools, even orphanages. School began at 6 or 7 and elementary school lasted 3-4 years, it was called "First Letters". It was followed by "Circular" and then "Superior" studies. Children were also taught to sing and play musical instruments. Singing was an important part of religious instruction.

Scribes and documents

The residents of the city had frequent need of scribes and clerks. The profession was regulated by the state. There were thousands of documents created, notarized and sealed every day. This meany there were a huge number of people who could read and write professionally. You could find scribes all over the city, especially outside Hagia Sophia where they operated with portable desks, ink, quills and paper. Documents were often required in duplicate, a copy was supposed to kept on file forever. A huge number of these were kept in vast storage halls under the Hippodrome where they were filed and managed by government clerks. In the 12th century most of these documents were made on paper. Church documents were kept in storerooms attached to Hagia Sophia and were inventoried by church staff. All of these records, going back hundreds of years, were lost in the Fourth Crusade and its aftermath. Although all of these documents have been lost, many of the lead seals attached to them survived.

Church life

People attended the church that was nearest to their home or work. Everyone had to walk, so the distance to your chosen church was important. An emperor built a church in the Forum of Constantine so the merchants there had a church nearby. The idle public and the rabble could go where they liked. This often brought them to Hagia Sophia where they could incite riot and cause trouble. Hagia Sophia was well attended on feast days and special events like Easter. Some people would attach themselves to local popular shrines, like the Hodegon Monastery or the Blachernae shrine of the Theotokos, but the distance always placed a great part of the decision of where to go. People did seek out holy people, monks and hermits for their spiritual advice. Only priests or ordained monks could bless people or forgive sins. Unlike Roman Catholics, Orthodox Christians do not take weekly communion. This means they confess less often as well. Orthodox Christians attend church to hear and participate in the liturgy. Here they would venerate icons and relics. Miracles occurred all over the city and even repeated themselves on certain days of the week in particular churches. There were many Holy Wells in and around the city and some of these exist to this day in Istanbul where they are visited by Muslims and Christians. In Constantinople people received most of the official news in church from the priest. When the emperor was out of the city he issued a newsletter to the Hagia Sophia clergy which was in turn conveyed to the people from the pulpit of their local parish.

The famous Varangian Guard

The Imperial "Varangian" guard was composed mostly of Anglo-Saxon Englishmen during the reigns of the Comnenian emperors. Formerly it had been Viking, but this changed due to immigrants from England after the Norman Conquest. In 1088 5,000 of them were said to have sailed for Byzantium in 235 ships. They lived in a barracks on a street within the walls of the Great Palace that was protected by a great gate. Guardsmen integrated with the local population by taking wives and even being involved in commerce. When they returned home they took as many things, like clothes, jewelry and armor, back as possible. In retirement they maintained their connection to Constantinople and sometimes tried to recreate the lifestyle and thus enjoy the same high status they had known in Imperial service.

Muslims in 12th century Constantinople

In the 12th century there was a large mosque in the city that could hold thousands and was always crowded for Friday prayers. It served a large number of Muslims who were permanent residents or visitors to the city including ambassadors, merchants and Muslim soldiers who were in service to the emperor. The call to prayer was done publicly and could be recited by some Byzantines. Manuel I might have spoken some Arabic. There were many Arabic speaking people in the city, including Christians from Antioch and other eastern cities within the borders of the empire. The mosque existed for a long time without interference or harassment. Manuel I insisted that the profession of faith used when Muslims became Christians be changed so did not deny Allah by name; thus assuming the Christian God and Allah were one and the same. Crusading armies and their kings were horrified to discover the mosque as they passed through the city headed for the east. It must have been destroyed by the Fourth Crusade in the burning and sack of the city.

Icon Painters in Constantinople

Constantinople must have had 10,000 icon painters competing for business. Although we can assume that there were lots of freelance artists, most painters would have been part of a workshop or attached to a monastery. Icons, both new and antique, were sold in shops, from street kiosks, and even by street peddlers. There must have been a staggering range in artistic quality when so many painters are involved. Among potential patrons of icon painters the Imperial Court and the Patriarchal church would have been the most important. Every workshop and painter would have aspired to to work for them. Being an officially recognized painter could give an artist a level of protection, but you were only as good as your last icon. This is the eternal struggle of all artists - you can be famous one day and forgotten the next. No matter how good you think you are there is always someone better and cheaper competing for business. Icons could be created in cheaper materials to reduce their cost. Gold backgrounds could be substituted with cheap silver leaf which was then glazed in orange colored shellac to imitated gold. Icons could be painted on flat wood backgrounds instead of panels with hollowed out centers. Panels could be painted on cheaper woods (resulting in splits), be made of smaller pieces of wood glued together, or just made much thinner to save money on them. Painters could use cheaper pigments, too. One can assume that many Byzantine icons made for the mass market where produced in assembly line fashion, with one artist painting faces, another clothes and another doing backgrounds. Styles - even in icon painting - changed rapidly. Subject matter changed as well, pilgrims wanted icons of their own national saints, like Boris and Gleb for the Russians. The peddlers of icons who trolled the streets would also besiege potential customers inside and outside places like Hagia Sophia.

Fortunately for the 12th century Byzantine icon painter there were lots of of potential individual patrons with money. Many of them would have been people who knew artistic quality and fine technique when they saw it and would buy it when they found it. Below the Imperial court and the Patriarchate there were also wealthy nobles and rich monasteries who were knowledgeable patrons of art. There was also a business in the repair and restoration of old icons.

There were many portrait painters in the city, one named Andreas became famous enough that a historian recorded his name. His dad was a cleric in Hagia Sophia.

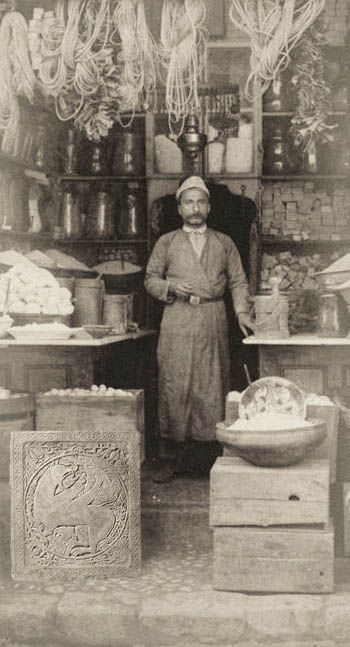

Shops operated from columned porticos. Merchandise was offered on the street and within the store. Most shops were family operated.

Shops operated from columned porticos. Merchandise was offered on the street and within the store. Most shops were family operated. Constantinople was served by aqueducts to fountains and open air cisterns around the city. Fountains would have been decorated with ancient statues and sculpture like this. People drew much of their water from wells that accessed underground cisterns.

Constantinople was served by aqueducts to fountains and open air cisterns around the city. Fountains would have been decorated with ancient statues and sculpture like this. People drew much of their water from wells that accessed underground cisterns. The city had many gardens and even vineyards. Many of the streets were arcaded.

The city had many gardens and even vineyards. Many of the streets were arcaded.

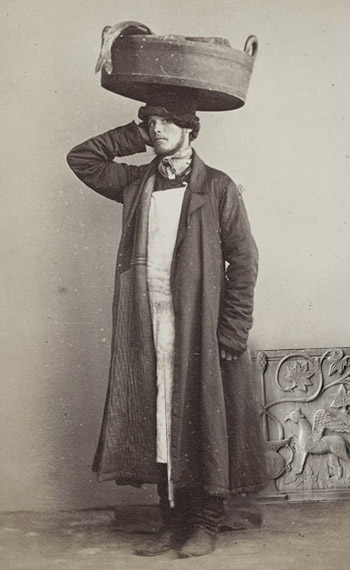

The streets were full of people who delivered fresh and prepared foods or every kind. Water was also delivered right to your door.

The streets were full of people who delivered fresh and prepared foods or every kind. Water was also delivered right to your door. Constantinople was a late antique city of columns, forums and paved streets. Some streets and shops were lit at night.

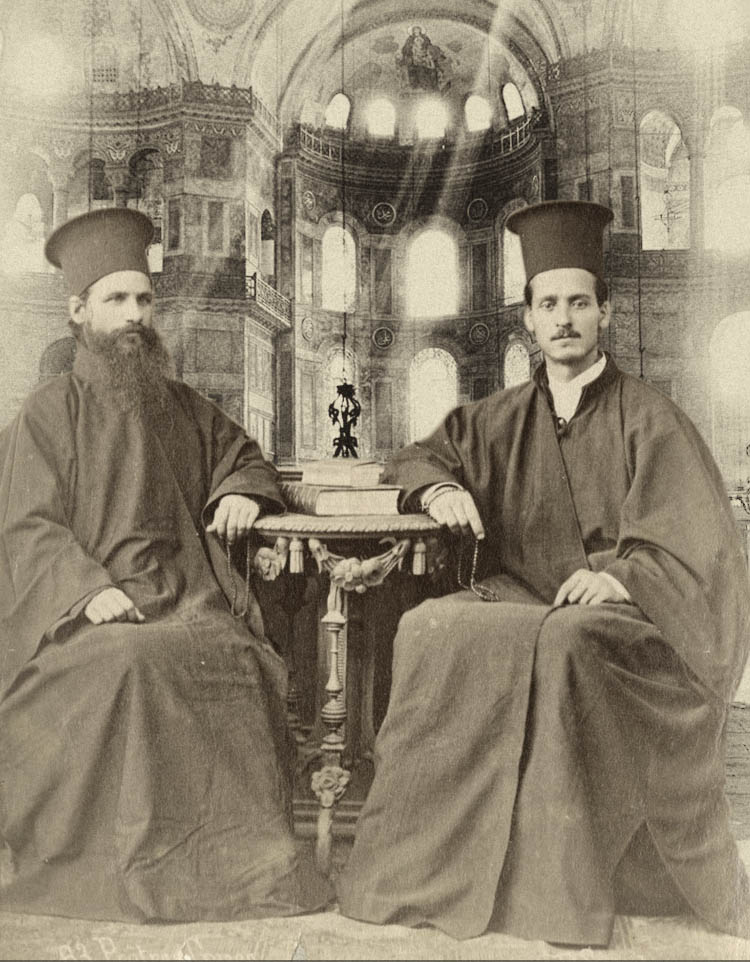

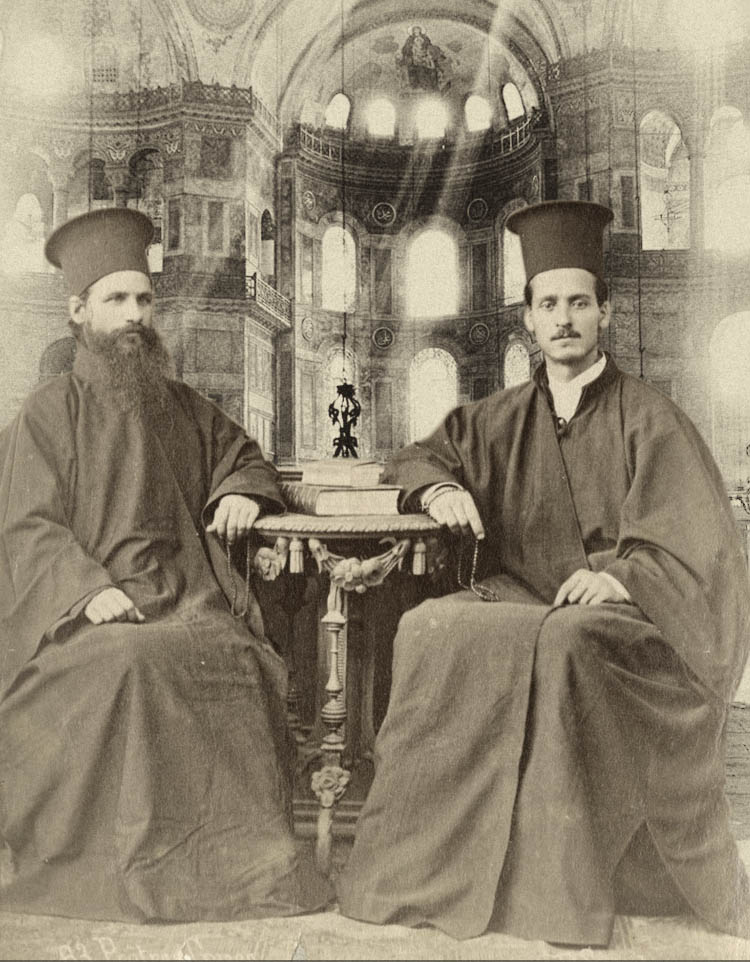

Constantinople was a late antique city of columns, forums and paved streets. Some streets and shops were lit at night. There were many priests, monks and nuns. Aristocrats and rich merchants founded and endowed convents for the female members of their family to retire to. Not all of them became nuns. Women could spend long periods of time living in nunneries as places of refuge.

There were many priests, monks and nuns. Aristocrats and rich merchants founded and endowed convents for the female members of their family to retire to. Not all of them became nuns. Women could spend long periods of time living in nunneries as places of refuge. The city was the destination of pilgrims from all over the world. Every year, at Easter, the relics of Christ's Passion were exhibited in Hagia Sophia. Hundreds of thousands of people viewed them.

The city was the destination of pilgrims from all over the world. Every year, at Easter, the relics of Christ's Passion were exhibited in Hagia Sophia. Hundreds of thousands of people viewed them. Women were very involved in the production of textiles and clothing. They also operated shops.

Women were very involved in the production of textiles and clothing. They also operated shops. Fashions changed rapidly in the 12th century. Men's fashions could be outlandish - even foppish. All men wore hats or turbans. Belts were decorated with buckles of bronze, silver and gold.

Fashions changed rapidly in the 12th century. Men's fashions could be outlandish - even foppish. All men wore hats or turbans. Belts were decorated with buckles of bronze, silver and gold. Imperial clothing was made in specialized shops near the Great Palace.

Imperial clothing was made in specialized shops near the Great Palace. Women wore beautifully ornamented clothes. Much of this work was done at home. Byzantine women were expert seamstresses and tailors.

Women wore beautifully ornamented clothes. Much of this work was done at home. Byzantine women were expert seamstresses and tailors. Hauling water and food was a hard job which was done by both men and women. Many of them could serve you wine, bread or fried delicacies in the streets. Some of them were attached to taverns.

Hauling water and food was a hard job which was done by both men and women. Many of them could serve you wine, bread or fried delicacies in the streets. Some of them were attached to taverns. Most Constantinople homes had courtyards. Residents would get water here, do cooking or their washing here. Since people normally lived in family compounds or near their work these activities could be communal.

Most Constantinople homes had courtyards. Residents would get water here, do cooking or their washing here. Since people normally lived in family compounds or near their work these activities could be communal.

A living history and art museum

A living history and art museum

The citizens of Constantinople were sophisticated consumers of wine of all kinds. Grapes were grown on low stakes and as rampant vines and in trees. The best wines came from nearby Bithynian Bursa, Cyzikus and Nicaea. The finest Bithynian wine was the white theraia ampelos grape, sweet and thick like honey. It came in three grades with the finest being reserved for the Imperial court. The rarest wines were created in small batches and came in small amphora, they were described as being "fit for a king". Cheaper wines were described as watery. Sweetness was what made a wine more desirable. in 1307 the Ottoman Sultan Osman ordered the destruction of the Bithynian vineyards in order to drive all of the Christian farmers from the land. The Turks were nomadic herders, not settled farmers. This created the first-ever shortage of wine in Constantinople. It also increased the cost of wine and the value of vineyards. Another result was the migration of wine production to coastal producers and the shores of the Sea of Marmora. Soon after the Turkish conquest of Asia Minor they became passionate consumers of Bithynian wines themselves, which could only be grown by Christians.

The citizens of Constantinople were sophisticated consumers of wine of all kinds. Grapes were grown on low stakes and as rampant vines and in trees. The best wines came from nearby Bithynian Bursa, Cyzikus and Nicaea. The finest Bithynian wine was the white theraia ampelos grape, sweet and thick like honey. It came in three grades with the finest being reserved for the Imperial court. The rarest wines were created in small batches and came in small amphora, they were described as being "fit for a king". Cheaper wines were described as watery. Sweetness was what made a wine more desirable. in 1307 the Ottoman Sultan Osman ordered the destruction of the Bithynian vineyards in order to drive all of the Christian farmers from the land. The Turks were nomadic herders, not settled farmers. This created the first-ever shortage of wine in Constantinople. It also increased the cost of wine and the value of vineyards. Another result was the migration of wine production to coastal producers and the shores of the Sea of Marmora. Soon after the Turkish conquest of Asia Minor they became passionate consumers of Bithynian wines themselves, which could only be grown by Christians.

Above is a wonderful reconstruction of the Chalke - Bronze - Gate to the Great Palace Above the door on the right is the famous mosaic icon of Christ. The Chalke Gate was decorated with bronze and marble sculptures and had huge bronze doors. On the left is the famous elevated passage that led from the Great Palace to the

Above is a wonderful reconstruction of the Chalke - Bronze - Gate to the Great Palace Above the door on the right is the famous mosaic icon of Christ. The Chalke Gate was decorated with bronze and marble sculptures and had huge bronze doors. On the left is the famous elevated passage that led from the Great Palace to the

On the right you can see an image of a Byzantine doctor in his official uniform (notice the turban), he is holding medicine in a glass or metal vial. This is a portrait of a real man. He must have been very proud of his forked beard. Doctors would have carried medical handbooks like this.

On the right you can see an image of a Byzantine doctor in his official uniform (notice the turban), he is holding medicine in a glass or metal vial. This is a portrait of a real man. He must have been very proud of his forked beard. Doctors would have carried medical handbooks like this. The twins are seen in the streets of Constantinople. A man drags them to a hospital.

The twins are seen in the streets of Constantinople. A man drags them to a hospital.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints