1437 Visit to Constantinople and Hagia Sophia by Pero Tafur

CHAPTER XIII: Voyage to Constantinople - Shipwreck - Tafur is almost drowned - A fight between Catalans and Genoese - Two embassies arrive for the Emperor of the East - Chios - Troy - The Dardanelles - Pera.

CHAPTER XIII: Voyage to Constantinople - Shipwreck - Tafur is almost drowned - A fight between Catalans and Genoese - Two embassies arrive for the Emperor of the East - Chios - Troy - The Dardanelles - Pera.

THERE was a ship from Ancona at Rhodes, and I contracted with the captain to carry me to Constantinople, and we sailed and came to the island of Samos, which is in the Archipelago, leaving on the right hand the castle of S. Pedro, which is on the mainland of Turkey, and on the left, the island of Cos, which belongs to the Order of Rhodes. We continued our course towards Chios, where we came upon a ship of that place, and they told us that the ships and galleys, which had come from the Council to take the Emperor of Greece to Europe, were anchored in the harbor of Chios, and we set sail and passed, leaving the island on the left, but the wind did not favor us, and when it failed we had to anchor beside the island and remain there that night. The next morning we saw approaching us two great galleys, and two lighter ones, and they came alongside and ordered us to return to Chios, otherwise they would fight us, and we had to do this, as we could not resist them. This was so that we should not know what they were about, for the Genoese had taken those galleys and armed them, intending to go to the harbor of Alexandria, and to capture two Catalan galleys, the En-Casa-Sages, and the En Sirviente, which were there. We were forced to return with the galleys and to anchor in the harbor, and we remained there all day. At midnight a great storm arose, and as we were insecurely grappled, our anchor broke away and caught a carack, which had been burnt and sunk in ancient times during the war between the Venetians and the Genoese, the bows of which remained above the water, and our ship struck it, and it stove us in and we sank, and it was then day. The sailors, in great peril from the sea which was very high, reached shore with difficulty, but as for me, when the ship sank, I was left in the water clinging to a piece of wreckage. Certain gentlemen who were there, Messer Nicolao de Meton, captain general, and some bishops and French gentlemen, gave orders to rescue me, but none dared venture. Then some Biscayans took a skiff from a galley, and came out to me and carried me to shore, but I was almost exhausted by the water and the cold, for it was Christmas. I found there the Bishop of Viseo in Portugal, and he took me with him and attended to my needs. There the French gentlemen heard from me of the death of the Grand Master of Rhodes, and certain Knights of the Order arrived, and with them the Commander of Pulaque, and when the storm abated he was carried to Rhodes in a galley, and was made Marshal of Rhodes. He was that one who brought the Bull to Castile, and then he had lost one eye, but not when I now saw him, and he was a very good knight and a man of great renown.

We remained there in Chios until the galleys went out against the Catalans, and it was on this wise. When they arrived at the harbour of Alexandria they found the Catalans there, and when the Catalans saw them they ran one of the galleys aground, and the larger galley, which was very powerful, took up the men, and they fought all that day and night, and the Moors looked on. At dawn a land wind arose, and the Catalans sailed out to sea, but the Genoese did not dare to follow, since on the open sea, with a fair wind, they would have had the worst of it, and leaving the other ships well guarded, the Catalans sailed for Rhodes, and the Genoese returned to Chios, where we remained. Having dragged our ship ashore, we refitted it, but the bulk of the merchandise was lost, and I also lost many things which I had brought from the East.

The ambassadors took their ships and left the harbor and came to the Council, and disembarked at Nice in Provence. This embassy was the one which had come to the Emperor of Greece, to obtain his agreement with the Council. It was a very rich and magnificent embassy, composed of well-selected men. But when the Venetians heard of it, and saw the great prejudice which was being stirred up against Pope Eugenius, who was a native of that city, they sent out another embassy to the Emperor, and the two met at Constantinople, and there was a great dispute as to who should bring the Emperor, and they armed themselves to fight. Thereupon the Emperor let it be known that he would go with neither embassy, but that he intended to go with his own ships, and he asked them to depart and not to hinder his passage, and they had to agree. Those of the Council came to Chios, as I have related, and the Venetians made as if to enter the Black Sea. Nevertheless, an agreement was come to between them and the Emperor, and when the others had departed they returned, and took the Emperor within a few days, and carried him to Italy to the port of Venice.

I remained in this island of Chios for twenty days and had nothing to do. I then departed for Turkey, which is only a short distance away, to a place called Foja-Vecchia, which, they say, is one of the ports of Turkey, where there is a Genoese settlement, and I found there a friend of mine whom I had known in Seville, and I asked him, since he had some influence with the Turks, to send one of his people with me to Troy, and to hire horses for me, which he did. I traveled by land for two days to that place which they say was Troy, but found no one who could give me any information concerning it, and we came to Ilium, as they call it. This place is situated on the sea opposite the harbour of Tenedos. The whole of this country is strewn with villages, and the Turks regard the ancient buildings as relics and do not destroy anything, but they build their houses adjoining. That which made me understand that this was, indeed, ancient Troy, was the sight of such great ruined buildings, and so many marbles and stones, and that shore, and the harbor of Tenedos over against it, and a great hill which seemed to have been made by the fall of some huge building. But I could learn nothing further, and returned to Chios. Here I found my ship refitted, and in two days we set sail. The island of Chios yields much gum, and has been populated by the Genoese, who took it from the Greeks, and the rulers call themselves Mayoneses, and since they cannot defend the place, they pay tribute to the Genoese who raise their standard there. The Genoese have need of that island for their voyages to the Levant and the Dardanelles.

We departed and put out to sea, and a great tempest arose which damaged the ship, but the sailors, being very skilled in that art, repaired the damage as best they could, and, leaving on the left hand the island of Mytilene, which also belongs to the Genoese, we doubled the Cape of S. Maria and came to the island of Tenedos, where we anchored and disembarked. While the ship was being refitted we set out to see the island, which is some eight or ten miles about. There are many conies, and it is covered with vineyards, but they are all spoilt. The harbor of Tenedos looks so new that it might have been built to-day by a master-hand. The mole is made of great stones and columns, and here the ships have their moorings and excellent anchorage. There are other places where ships can anchor, but this is the best, since it is opposite the entrance to the Straits of Romania [Dardanelles]. Above the harbor is a great hill surmounted by a very strong castle. This castle was the cause of much fighting between the Venetians and Genoese until the Pope sentenced it to be destroyed, that it might belong to neither. But, without doubt, this was very ill-advised, since the harbour is one of the best in the world. No ship can enter the Straits without first anchoring there to find the entrance, which is very narrow, and the Turks, knowing how many ships touch there, arm themselves and lie in wait and kill many Christians. From there one sees many buildings of Troy, and certain Greeks who live there can even give some account of the place.

The next day we departed, and sailing on we entered the Straits, which are very narrow. On the Turkish side the water is very shallow. These Straits are called the Dardanelles, and here was the door and harbor of Troy. On the side towards Greece the water is very deep. Here stands the tower of Vituperio where Achilles was found with Patroclus, or so they say that wish it so. In this place the Straits are so narrow that on a clear day one can see a standard raised on the other side. So, passing through these Straits, and leaving certain villages on the Turkish side and on the Greek side, we reached the city of Gallipoli, a notable place, and a good harbour with an excellent castle. This was the first place taken by the Turks when they passed over into Greece, and they left the wall and castle standing, which they did not do elsewhere, so that if they chanced to be defeated they could be succoured from there. We departed from Gallipoli and came to the Sea of Marmora, which is an inland circular sea of about eight leagues across, and they call it Marmora, because from it came all the marble for Constantinople, as well for the walls as for the city, and it belongs to the Greeks. From there we came to a town called Eregli, and to . another called Silumbria, which two places the Turks allowed the Emperor to retain in times past out of courtesy and for his support. Departing from there, the next day at dawn, we saw a very high mountain, more than a hundred miles off, and they told us that it was St. Sophia, which is in Constantinople, and we came to a place about two miles from the city where we remained that night The next morning I sent the boat to the city of Pera, to give news of my coming to the captain of a ship, called Juan Caro, a native of Seville, who was my good friend and whom I knew to be there. He came out with his friends in their boats to greet me. I desired to go at once to make my reverence to the Emperor, but they importuned me so much, saying that I should disgrace them if I did not go first to Pera where they had their houses, that I had to comply. I and my companions entered the boats of the Castilians, and our ship came with us, and we entered the harbour of Constantinople, and we then left it and went on and anchored at the quay of Pera, which is one of the finest in the world. Any ship, however great, can lie in clear, deep water with its bowsprit on land, so that better anchorage could not be had. I landed in company with the Castilians, and with other friends of theirs of divers nations, and we went to the church to pray. There I found the podesta who governs the place, and he received me very kindly, asking for news of the West, and protesting that what ever I had need of should be supplied at once, and so we parted. I took lodgings with the Castilian captain where I had, indeed, an excellent reception, and when I arrived I found a great present of wine and fowl, which the podesta had sent me. The following day the Castilians who were in Constantinople and Pera came to see me, and I recognized some whom I had seen in Castile, among them Alfon de Mata, squire to Don Juan, our Master, whom God protect.

He begged me to present him to the Emperor of Trebizond, because he had come with the ambassadors of the Council, and was now ruined, and I did speak to the Emperor, although he was himself equally ruined, having been exiled from his country with the Empress of Constantinople, his sister, and he received him into his service, and gave me the same day a bow and arrows which I still have.

CHAPTER XIV: Constantinople - The Emperor John Palaeologus - Tafur's family tree - The story of the Fourth Crusade - Tafur's reception at Court - Departure of the Emperor for Europe

AFTER two days, during which time I rested myself, I went to make my reverence to the Emperor of Constantinople, and all the Castilians accompanied me. I arrayed myself as best I could, putting on the Order of the Escama, which is the device of King Juan, and I sent for one of the Emperor's interpreters, called Juan of Seville, a Castilian by birth, and they say that the Emperor chose him to be interpreter because he sang him Castilian romances to the lute. He came with me to the Palace, and went in to advise the Emperor that I was there to make my reverence, and they made me wait an hour while the Emperor sent for certain knights and prepared himself. I then entered the Palace, and came to a hall where I found him seated on a tribune, with a lion's skin spread under his feet. I made my reverence there, and told the Emperor that I had come to see his person and estate, and to take knowledge of his lands and lordships, but principally to learn the truth concerning my lineage, which I had been told had sprung from that place, and from his Imperial blood, and I commenced to tell him the manner in which this was said to have come about. He replied at once that I was very welcome, and that he was greatly pleased to see me, and as to that which I spoke of he would order the ancient records to be searched, so that the truth of everything might be ascertained. He asked me for news of the Christian lands and princes, especially concerning the King of Spain, my Master, and of his estate and his war with the Moors, and I replied to everything to the best of my knowledge, and so took leave of him and went to my lodging. The next day he sent for me to ask me to go hunting, and he sent horses for me and mine, and I went with him, and with the Empress, his consort, who was there, and that day he told me that he was now acquainted with the matters about which I inquired, and that on his return he would order me to be exactly informed concerning them, and I thanked him. When we returned, about Vesper time, after we had dismounted, he sent to summon before him those whom he had instructed to make search concerning my inquiries, and it was on this wise.

They say that formerly (I do not remember the actual time) an Emperor of Constantinople sent throughout his lands to order that the nobles should pay taxes and render service and make contributions, in the same way as the villeins. The nobles, in view of so great an abuse of their charters, spoke with his eldest son and heir, and persuaded him to take their part and to reason with the Emperor, his father, that he should refrain from leaving so bad a name behind him, for his proposals were against order and justice, and could only force the nobles to take up arms against him, which could not be avoided if he persisted in his evil purposes. The prince accepted the charge of the nobles, and promised to do all in his power, and he spoke to the Emperor, his father, and begged him, of his grace, not to do this against the nobles of his country, since it was due to them that he was ruler, and that they sustained and honored him; further, that if he opposed them he would involve his country in great peril and labor, and that he would find that he could not enforce his will on them. When the Emperor heard this he was very incensed against the prince, his son, and banished him from his court, and he betook himself, as they say, to the city of Adrianople, which is today the headquarters and court of the Grand Turk. When he arrived there the noise of it went throughout the Empire, and presently there was a general rising of the nobles and their adherents, and they gathered together and took the prince, and came with a great host to Constantinople where the Emperor was, a journey of about five days. The Emperor, when he knew of this, went out and encamped with all his commons, and they were thus arrayed one against the other. The prince sent once again to beseech his father that he should refrain from causing such great injury and ruin, since otherwise he would have to fight with him. But the Emperor was much more incensed than before, saying that matters must now proceed, and that he would make the prince and all those with him pay with their lives. When the prince saw this, and that a contest was imminent, he made an agreement with his father that the Emperor should withdraw to Constantinople, and that he should return to Adrianople, and that they should then come to terms. The prince did all this in order to avoid fighting with his father. And it fell out so, and each returned to his place.

Now when the prince saw that the question could not be settled without fighting, he approached one of the princes, his brother, and recommended the people to him, and he commended him to the people, and said that God would never suffer him to fight with his father, nor even to live in a country where such a thing was possible, and he departed and came to Spain, and arrived in Castile at the time when Don Alfonso was reigning, who conquered Toledo, and whom some call Alfonso of the Pierced Hand. Here the prince was known as Count Don Pedro, and was father of Don Estevan Yllan. The Greek nobles, when they found themselves bereft of such a captain, for he was a valiant knight, as he had proved himself by many feats of arms, both before and after he came to Spain, took the younger brother, although he was but a youth, and kissed his hand, and called him Emperor of Greece, and set out with him from Adrianople with all their men-at-arms. They came up against Constantinople, with intent to place this youth on the Imperial throne, and the Emperor, when he was advised of it, did as before and marched out of the city against him, and there was no course but to fight. The Emperor was vanquished and captured, and great numbers of his people were slain and taken, and the nobles entered the city as great victors and placed the young prince, their captain, whom they had brought with them, on the Emperor's throne. They set a strong guard about the person of his father, and after a few days' illness he died, and the prince remained in peaceful possession of the Empire. He repealed the laws which his father had made, and made others more favourable to the nobles than before, and for this cause they say that there is not so much liberty for nobles in any part of the world as in Greece. Nor are the villeins anywhere so much in subjection, since they are in fact slaves to the nobility. But, to-day, for the sins of Christians, both nobles and villeins are afflicted with a grievous servitude, since their lords are the Turks, the enemies of the Faith.

The other prince, when he came to Castile, was very well received and much honored by the King, and they say that the King was preparing to make war on the Moors, and he married the prince to one of his own legitimate sisters, arid left him to govern the Kingdom while he went to the war. He is said to have been a very noble knight, vigorous, frank, and very discreet. They called him Don Peryllan, and he it was, they say, who entered Toledo and set up the King there. Moreover, when the city revolted he recovered it for him, fighting against the rebels and overcoming them. For this cause, and as recompense for this deed, they say that all those privileges were granted to him, which the citizens of Toledo enjoy to this day. He is buried in the chapel of the ancient kings in Toledo, and high up in the roof he is painted on horseback with his standard and arms, the which are the same as those now borne by the most virtuous and bounteous Don Fernant Alvarez de Toledo, Count of Alva, for he is descended in the direr line from that prince of Greece who came to Castile. I also carry those arms, for I come also of that line, and that Don Pero Ruyz Tafur, who was prominent in the taking of Cordova, was a grandson of Count Don Estevan Yllan, the son or grandson of Don Peryllan, the prince of whom I am speaking. It would be fitting, but for prolonging this writing, to relate from the history of Castile, how many of them from father to son are descended from that line until now. And if I carry bars on my escutcheon, it is because by marriages the descent has become confused, but the true arms are checky.

When I was acquainted with all this, I inquired of the Emperor why he did not carry those arms which it was formerly the custom for the Emperors to wear, that is the arms of my family, and he told me that some hundred or hundred and fifty years ago, or more, the Venetians prepared a great fleet, saying that it was for the assistance of the Emperor against the Turks, and they came with the fleet to Constantinople, and were very well received by the Emperor and all the Greeks, and they lodged everywhere in the city. But it appears that they had already plotted what they put in practice, for they rose with the citizens against the Emperor, and fought with him, and since he was wholly unprepared for such treason, they succeeded in driving him out of the city, and many were slain. He fled to Morea, which was called formerly Achaia, a principality of the heirs of the Empire, and the Venetians occupied the city and remained there for fully seventy years, and they carried away many holy relics, which are now in Venice, the bodies of St. Helena and St. Marina, and many other relics. They despoiled a number of magnificent buildings, and carried off two great columns which they set up, with their Patron Saint upon them, on the sea-shore. They are as high as towers and so well preserved that it is difficult to believe they could ever have been moved. Above the door of St. Mark's are four very great horses of brass, thickly gilt with fine gold. There are also jaspers and marbles and other things, all of which they carried off from Constantinople during the time of their dominion. They were even on the point of transferring the government from Venice to Constantinople, but desisted on the advice of an elder, who said that they ought never to leave the city from which they had conquered all the others. While the Venetians held Constantinople the Emperor died, as well as his son, and there remained only a grandson, who married a daughter of the King of Hungary and became a worthy knight. He agreed with the people of Constantinople and the surrounding country that on a given day they should all rise, and he would be ready with as great a force as he could muster, and would succour the city, and when it was taken all should be his, and it was so.

On the appointed day the people rose against the Venetians, and shut them up in one part of the city so that they, could not reach the ships, and they sent for that prince, who entered the city, and killed and captured all the Venetians, and sat himself on the Imperial throne, and the people kissed his hand and acknowledged him as their ruler. They took much spoil from the Venetians and much money by way of ransom, and he held dominion in peace. Now they say that this Emperor, who thus recovered the Empire and held it, could never be prevailed upon to relinquish the arms which he formerly bore, which were and are two links joined, and to assume the Imperial arms, which belong to the throne. But he replied always that he had won the Empire bearing those arms, and nothing would induce him to part with them, and so it is to this day. Nevertheless, the old arms, which are checky, can still be seen on the towers and buildings and the churches of the city, and when the people put up their own buildings they still place the old arms upon them. I insisted, as best I could, that the Emperors should still wear those arms since they are the real arms of the Empire. Further, that it is the office which gives the authority, and not the person who restored it, especially since the people recovered the city and made him their lord. To this the Emperor replied that the matter was still being debated between himself and the people. I, having been informed of all this, told the Emperor what had happened in Spain, and he told me what had happened there. This was all I could learn of the affair of the arms, and of the manner in which it came about.

From that time onwards the Emperor treated me with great affection and as a kinsman, and he desired greatly that I should remain in his country and marry there and settle down, and I had some thoughts of doing so in view of what I have related, for the city is badly populated and there is need of good soldiers, which is no wonder since the Greeks have such powerful nations to contend with. I found in the city many Castilians and persons of other Latin nations in the Emperor's service, and while I was there they showed me great honor and esteem. That day a knight of the household who was there invited me to dinner on the following day, and I accepted. After Mass I went to his house, where he was awaiting me, and I dined with him, and he showed me his wife and children, treating me in a very friendly manner. After dinner he sent everyone away and went to his room and put on his collar of the Order of Escama, the device of our King and Master, and he came to me and said in the Castilian tongue: " Sir knight, you are right welcome. See here is my house with all that is in it at your disposal, as if for my own brother, because I have received great honor and many benefits from your King, and from the knights of your country much hospitality, and if I have not spoken to you until now in your own tongue in public, it is because we hold it for a disgrace at any time to give up our own language and speak a strange one. Nevertheless, for the great love which I have for your nation, and for you, from henceforth when we are alone I will bear myself in all things as a Castilian, like yourself." From that hour I received much honor from this knight, and he brought one of his sisters to me, a very beautiful woman, saying that while I was there I should serve her as a friend, and he commended me to her. Indeed, I believe he desired me to marry her. From this lady I received many things, especially two pavilions which I took to Castile. The one I gave to the King, and the other I still have.

This day the Emperor sent for me to go hunting, and we killed many hares, and partridges, and francolins, and pheasants, which are very plentiful there, and when we returned to the Palace I took my leave and went to my lodging, where he had ordered that I should be provided with whatever I had need of. Without doubt, it was the Emperor's wish to show me much honor and favor, and from that day onwards, when he or the Empress, his consort, desired to hunt, he sent horses for me, and I went with them, and they said that they had great pleasure in my company. After fifteen days of my visit had passed, the Emperor had to depart m the Venetian galleys to meet the Pope, and he begged me repeatedly to accompany him, which I should have done had I not been forced to excuse myself on the plea that I was obliged first to see Greece, Turkey, and also Tartary. When the Emperor saw that he could not persuade me, he commended me to the Empress, his wife, and to Dragas, his brother, who was heir to the Imperial throne - that one whom the Turks have since killed-and he departed in great splendor. There went with him two of his brothers, and 800 men, all noblemen of high rank. On the day of his going there was a great celebration, and everyone went in procession with the members of the Religious Orders to the place of embarkation, and a great company went one day's journey out to sea with the fleet, and I went also. I then took my leave and returned to Constantinople, but the Emperor gave me licence very unwillingly, saying that if I had had my people with me he would not have let me go. So I left him, he commanding me to visit him before returning to my country, which I promised and later performed.

CHAPTER XVII: Return to Constantinople - St. Sophia - The Relics - Statue of Constantine (Justinian) - A Holy Picture - The Hippodrome - The Serpent Column - A statue called The Just - The Palace - The Library - The miserable condition of the city - Summary Justice - A feint by the Turks - They are bought off

WE sailed in the same ship, and continuing our course we returned to Trebizond, where, as I have said, the Emperor did his best to detain me, but he could not succeed, and we departed and came to Constantinople. But orders having been issued that no ships coming from the Black Sea were to enter the harbor, either at Constantinople or Pera, because it was feared that they would bring the plague with them, they built a shelter two leagues from Constantinople where the ships could discharge their cargo, and where they had to remain for sixty days unless they were prepared to put to sea again. Certainly the foreign nations bring much sickness with them, and I myself saw in that lodging men dead of plague. I sent one of my men to ask permission of the Despot Dragas to enter the city, notifying him that I and my people had left the ship, and that I had not lodged with the others, but had remained two days in the fields. He ordered a boat, which was very well fitted out, to be sent for me, and certain of my friends came out to receive me. I sent my people to the place where they were to lodge, and went to make my reverence to the Despot, who received me very graciously, as did also the Empress and her ladies. The Empress inquired of me how I had fared in the Black Sea, especially if I had seen her brother, the Emperor of Trebizond, and her other brother was there at that time. I told them what had happened when I saw the Emperor, and they thanked me much, and the Empress said: "You could not have done more if you had been of our nation," and I replied: "Lady, I did that which was due from a good Christian." I then took my leave and returned to my lodging, very well attended by the nobles of the city.

On the day following I went to the Despot, and asked him if he would be pleased to direct that I should be shown the church of St. Sophia and its relics, and he replied that he would do it with pleasure, and that he himself desired to go there to hear Mass, as did also the Empress and her brother, the real Emperor of Trebizond. We then went to the church to Mass, and afterwards they caused the church to be shown to me. It is very large and they say that in the days of the prosperity of Constantinople there were in it six thousand clergy. Inside, the circuit is for the most part badly kept, but the church itself is in such fine state that it seems to-day to have only just been finished. It is made in the Greek manner with many lofty chapels, roofed with lead, and inside there is a profusion of mosaic work to a spear's length from the ground. This mosaic work is so fine that not even a brush could attempt to better it. Below are very delicate stones, intermixed with marble, porphyry, and jasper, very richly worked The floor is made of great stones; most delicately cut, which are very magnificent. In the center of these chapels is the principal one which is very large; the height is such that it is difficult to believe that cement can hold it together. In this chapel there is similar mosaic work, with a figure of God the Father in the center. From below it looks the size of an ordinary man, but they say that the foot is as long as a spear, and from eye to eye the distance is many spans in length. Here is the great altar, and here one can see all the grace and richness appertaining to geometry. Beneath this chapel there is a great cistern which, they say, could contain a ship of 3000 botas in full sail, the breadth, height and depth of water being all sufficient. I know not if such a statement can be supported, but I never saw a larger in my life and do not believe that one exists. The Despot and the others directed the clergy to bring out the holy relics. The Despot keeps one key, and the Patriarch of Constantinople, who was there, the other. The third is kept by the Prior of the church. The clergy, in their vestments, brought out the relics in procession, which were: Firstly the lance which pierced Our Lord's side, a marvelous relic; the coat without a seam, which must at one time have been violet, but which had now grown grey with age; one of the nails; and some thorns from Our Lord's crown, with many others, such as the wood of the Cross, and the pillar at which Our Lord was scourged. There were also several things of Our Blessed Lady the Virgin, and the gridiron on which St. Lawrence was roasted, and many other relics which St. Helena took when she was at Jerusalem and carried here, which are much reverenced and closely guarded. God grant that in the overthrow of the Greeks they have not fallen into the hands of the enemies of the Faith, for they will have been ill-treated and handled with little reverence. As we came out we saw at the door of the church a great column of stone, higher than the great chapel itself, and on the top is a great horse of gilded brass, upon which is a knight with one arm raised, pointing with the finger towards Turkey, and in the other he holds an orb, as a sign that all the world is in his hand. One day it was blown down in a great storm, and the orb fell from the hand, and they say that it is as large as a 15 gallon jar, but from below it looks like an orange, so that one can judge how high the statue is. They say that to secure that orb, and to fasten the horse with chains, to prevent its being blown down in the high winds, cost 8000 ducats. This knight, they say, is Constantine, and that he prognosticated that from that quarter which he indicated with his finger would come the destruction of Greece, and so it was. That day we were occupied until midday admiring the church and its circuit. Outside this church are great squares with houses where they are accustomed to sell wine and bread and fish, and more shell-fish than anything else, since the Greeks are in the habit of eating them. In certain times of fasting during the year they do not only confine themselves to fish, but to fish without blood, that is, shell-fish. Here they have great tables of stone where they eat, both rulers and common people, together.

The Despot and the Empress and her brother then returned to the Palace, and I went to my lodging. The next day I went to the church of St. Mary, where the body of Constantine is buried. In this church is a picture of Our Lady the Virgin, made by St, Luke, and on the other side is Our Lord crucified. It is painted on stone, and with the frame and stand it weighs, they say, several hundredweight. So heavy is it as a whole that six men cannot lift it. Every Tuesday some twenty men come there, clad in long red linen draperies which cover the head like a stalking-dress. These men come of a special lineage, and by them alone can that office be filled. There is a great procession, and the men who are so clad go one by one to the picture, and he whom it is pleased with takes it up as easily as if it weighed only an ounce. The bearer then places it on his shoulder, and they go singing out of the church to a great square, where he who carries the picture walks with it from one end to the other, and fifty times round the square. By fixing one's eyes upon the picture, it appears to be raised high above the ground and completely transfigured. When it is set down again, another comes and takes it up and puts it likewise on his shoulder, and then another, and in that manner some four or five of them pass the day. There is a market in the square on that day, and a great crowd assembles, and the clergy. take cotton-wool and touch the picture and distribute it among the people who are there, and then, still in procession, they take it back to its place. While I was at Constantinople I did not miss a single day when this picture was exhibited, since it is certainly a great marvel.

There was a church at Constantinople, not so large as St. Sophia, but, as they say, much richer, which St. Helena built, desiring greatly to show her power. At the entrance were certain arches which were very dark, and they say that people were found there frequently committing the offence of sodomy, and one day a thunderbolt fell from Heaven and set fire to the church, and not one of those who was surprised in that sin was spared. The church they called Blacharyerna, and it is to-day so burnt that it cannot be repaired. There is also a monastery, called Pentecatro, which belongs to the monks of the Order of St. Basil (there is no other Order in those parts), and this also is very richly adorned with gold mosaics. In it are the vessels which were filled with wine at the marriage of Architeclinos, and many other relics, and it is the burial place of the Emperors. On one side of the city, towards the sea and over against Turkey, is a monastery for women, on a wall, called St. Demetrius, and one can see Turkey across the narrowest part of the Straits. Opposite to it on the Turkish side there is a tower where a chain was stretched from one side to the other, and when it was made fast the ships could not pass. This was done partly for display, and partly in order not to lose the tolls which were collected there, and this they call the Arm of St. George. At one part the Straits are so narrow that one can see a man passing on the opposite shore. Moreover, the sea is very shallow on the Turkish side, and so deep on the Greek side that a ship of any size, and however large, can lie against the walls of Constantinople, so that it looks as if one could jump from the walls on to the ship.

There is in Constantinople a great place made by hand, with porticoes and gateways, and arches below, where the people used in ancient times to watch the games when they celebrated their holidays, and in the center are two snakes entwined, made of gilded brass, and they say that wine poured from the mouth of one and milk from the other. But no one can remember this, and it seems to me that too much credit must not be attached to the story. There is a statue of a man in the center of this square, also of gilded brass, and they say that when merchants could not agree as to price they consented to go to this statue, which they called the Just, and what it signified as correct by shutting the hand, that was the true price of the goods, and both parties accepted it. There was once a nobleman who had a horse which was valued at 300 ducats, and a gentleman of those parts desired to buy it, and they could not agree on the price. They arranged, therefore, to go to the statue to determine the question, and they went there, and the purchaser took out some ducats and laid one in the hand of the statue, which thereupon shut its hand, giving to understand that the horse was not worth more, and the purchaser had the horse and the seller the ducat, but the seller was so incensed that he took out his scimitar and cut off the statue's hand, and after that it never judged again. When the buyer reached home the horse fell dead, and the hide and shoes fetched just a ducat. But I would place more faith in anything found in the Evangelists.

On the other side of this square is a bath with doors on either side opposite each other, and any woman accused of adultery was ordered by the judges to be brought there, and they made her go in by one door and come out at the other, and if she was innocent she passed through without shame, but if otherwise her skirts and chemise raised themselves on high without her perceiving it, so that from the middle downwards everything could be seen. This also it may be no sin to doubt. In the centre of this square there is an obelisk made of a single stone, in the same manner as that at Rome, where are the ashes of Julius Caesar, but in fact it is not like that one, nor is it fine nor ancient. They say that it was made for the body of Constantine. There are also many buildings about this square, and inside it, and they call it the Hippodrome.

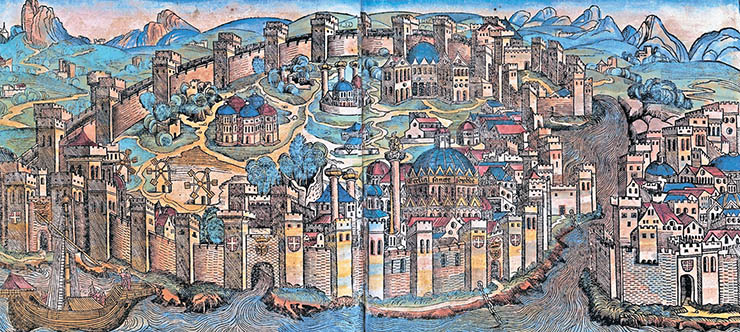

The city of Constantinople is made like a triangle, two parts in the sea and one on land. It is very strongly walled in a way that is a marvel to see. They say that the Turks came there and put the city in great straits, and he that had charge of the mines was amazed, and said to the Grand Turk: "Lord, this city is not to be taken by mining, for the walls are of steel and will never fall:" (This was said because the walls are very high and are made of great marble blocks bound together.) But as the Grand Turk was continuing his attempt, they told him that they had seen a man on horseback riding on the wall. He then asked a Greek who had been captured what this marvel was which they saw each night, namely, a knight riding round the ramparts on a horse, fully armed. He replied:

"Lord, the Greeks say as follows: when Constantine built his church, many men were employed on the work, and one day, as all were going to dinner, the chief master-builder ordered a child to stay and guard the tools. The child did so, and a very beautiful man on horseback appeared and said to him: `Why do you not go to eat with the others?' and the child replied: `Lord, they ordered me to remain here to guard the tools.' But the horseman replied: `Go and eat,' and the child replied that he dare not. Whereupon the horseman said: `Go without fear. I promise you that I will guard the church and the city until you return.' And the child went, but afterwards, being afraid of punishment, he did not return, so that the horseman remained in fulfilment of his promise, and they say that it was an angel."

But it might be said now that the child had returned, and the angel had ceased his guard, for the city is now captured and occupied. But for that time the Turk departed.

The Emperor's Palace must have been very magnificent, but now it is in such state that both it and the city show well the evils which the people have suffered and still endure. At the entrance to the Palace, beneath certain chambers, is an open loggia of marble with stone benches round it, and stones, like tables, raised on pillars in front of them, placed end to end. Here are many books and ancient writings and histories, and on one side are gaming boards so that the Emperor's house may always be well supplied. Inside, the house is badly kept, except certain parts where the Emperor, the Empress, and attendants can live, although cramped for space. The Emperor's state is as splendid as ever, for nothing is omitted from the ancient ceremonies, but, properly regarded, he is like a Bishop without a See. When he rides abroad all the Imperial rites are strictly observed. The Empress rides astride, with two stirrups, and when she desires to mount, two lords hold up a rich cloth, raising their hands aloft and turning their backs upon her, so that when she throws her leg across the saddle no part of her person can be seen. The Greeks are great hunters with falcons, goshawks, and dogs. The country is well stocked with game both for hawking and hunting, and there are quantities of pheasants, francolins, partridges, and hares. The land is flat and good for riding. The city is sparsely populated. It is divided into districts, that by the sea-shore having the largest population. The inhabitants are not well clad, but sad and poor, showing the hardship of their lot which is, however, not so bad as they deserve, for they are a vicious people, steeped in sin. It is their custom when anyone dies not to open the door of the house for the whole of that year except in case of necessity. They go continually about the city howling as if in lamentation, and thus they long ago foreshadowed the evil which has befallen them. On one side of the city is the dockyard. It is close to the sea, and must have been very magnificent; even now it is sufficient to house the ships. In the quarter over against Pera is a mole made by hand, where the ships are fastened. Here the salt water comes in and meets a river which enters the sea at that place. The distance from there to Pera is twice as far as a man could cast a stone. When the ships come to Pera to traffic with the Genoese, they first salute Constantinople and pay tribute, and criminal justice is administered from Constantinople for Pera and the whole country. These harbors of entry, the one and the other, are always full of ships, on account of the great cargoes which they discharge and load.

One day the Castilian captain who was there sent for me, because one of his men had been killed at sea by a Greek, with intent to steal his ship, and I went to him, and we took the criminal and the corpse to the Emperor that justice might be done. Although the Greeks did not wish it, yet out of his great regard for me, and because I said that our people might otherwise take vengeance upon those who were innocent, the Emperor sent at once for the executioner, and in front of the Palace he ordered the criminal's hands to be cut off, and his eyes to be put out. I inquired why they did not put him to death, and they replied that the Emperor could not order his soul to be destroyed. They told me also that when Charlemagne took Jerusalem, on the way by which his people had to return, many of them traveled through Greece and were killed by the Greeks, and that the others, when they heard of this, took the road through Tartary and Russia, where the inhabitants were Christians, and from there they passed into Hungary and Germany. It is said that the reason why the Russians of those parts are so beautiful, is that many Frenchmen settled there and married. The Emperor Charlemagne then came up against Constantinople, and made great war on the Emperor of Greece, but in the end they had to make peace, and the Emperor, as penance for the killing of those men, promised to fast during the whole of Lent, which they say is observed differently than with us (since the Greeks cannot reconcile it with their consciences to eat fish with blood, but only shell-fish, and, further, that no one, however great his crime, should be put to death, but that the punishment was to be loss of hands and eyes. In Greece, therefore, there are many maimed and blinded men. This is the manner in which the Despot gave us justice, and we were content with what he did.

During my stay in the city the Grand Turk marched forth to a place on the Black Sea, and his road took him close to Constantinople. The Despot and those of Pera, thinking that the Turks were going to occupy the country, prepared and armed themselves. The Grand Turk passed close by the wall, and there was some skirmishing that day, and he passed with a great company of people. I had the good fortune to see him in the field, and I observed the manner in which he went to war, and his arms, horses and accoutrements. I am of opinion that if the Turks were to meet the armies of the West they could not overcome them, not because they are lacking in strength, but because they want many of the essentials of war. On this day a great present was carried from Constantinople and taken to the place where the Turks were stationed. I thought that they would sit down and besiege the city, but they continued their march to the Black Sea against a people which had rebelled. It was, indeed, what I desired, for we had but few men, and it would have been difficult to make much resistance. It was, therefore, a gratifying thing to see so great a host depart without peril or labor. Would to God that the people of our country were closer at hand, for there are here neither ships nor fortresses, nor is there any protection except by fighting.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints