<

Alexander I, a handsome Byzantine playboy and polo player with thick blond hair to his shoulders and beard, was co-emperor with his brother Leo VI and they hated each other. Leo was first named co-emperor in 870 with his father Basil I, and Alexander was added as co-emperor 9 years later. Basil I was a professional wrestler and polo player who rose though the imperial court to seize the throne from Michael III, who was nicknamed the Drunkard. In a strange story Michael was Leo's father and Alexander was Basil's. They had the same mother. Everyone knew the truth of their parentage and it poisoned Leo's relationship with his family. Basil went out of his way to be mean to Leo.

Alexander I, a handsome Byzantine playboy and polo player with thick blond hair to his shoulders and beard, was co-emperor with his brother Leo VI and they hated each other. Leo was first named co-emperor in 870 with his father Basil I, and Alexander was added as co-emperor 9 years later. Basil I was a professional wrestler and polo player who rose though the imperial court to seize the throne from Michael III, who was nicknamed the Drunkard. In a strange story Michael was Leo's father and Alexander was Basil's. They had the same mother. Everyone knew the truth of their parentage and it poisoned Leo's relationship with his family. Basil went out of his way to be mean to Leo.

Alexander was only 41 when he ascended the throne, he must have thought he had many years ahead of him in power.

There was a famous zykanisterion, the Byzantine name for polo field, right in the Great Palace, that had been built by Theodosius II around 420. Basil I and two of his sons, Alexander and Constantine, were nuts about all sports especially polo. They hung out with other men with similar interests and promoted them at court, giving them patronage jobs.

Alexander was well educated, the sons of Basil were assigned the top scholars of the time as tutors.

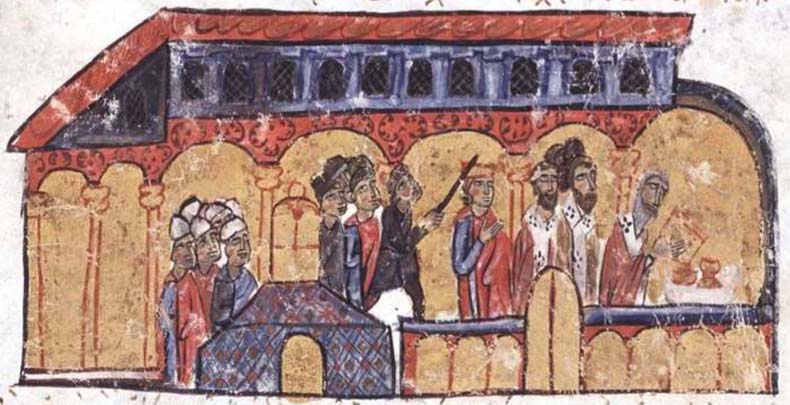

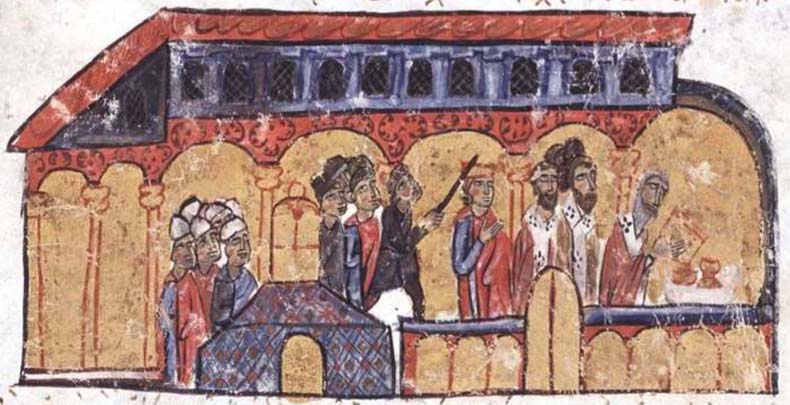

Alexander was rumored to have been in on an assassination plot against his half-brother in the Church of St. Mokios. Alexander was supposed to have joined his brother in the service, but he didn't show up, sending a message that he was ill. The assailant approached Leo as he stood before the Holy Doors of the Sanctuary during the Offertory and whacked at him with a club. He swung too high and the club glanced off a chandelier. This blunted its force. The club came down on Leo, hitting him in the head which left him bloodied, lying on the marble floor of the church, but still alive. Chaos erupted in the church. The court officials and clergy who had accompanied Leo into the church panicked. Leo should have died and was only saved by the chandelier. The emperor's attacker was seized and interrogated, but would not reveal who his accomplices were even under terrible torture. He was taken to the Hippodrome where his hands and feet were cut off before he was burned alive. You can see a manuscript illumination of the event below. It comes from the Madrid Skylitzes:

After Leo died Alexander reigned as sole Emperor for only a year 912-913. It is worth noting that Halley's Comet appeared that year and was seen as an omen of blood in Constantinople. Alexander consulted wizards about the comet to find out what it meant for him and his reign.

After Leo died Alexander reigned as sole Emperor for only a year 912-913. It is worth noting that Halley's Comet appeared that year and was seen as an omen of blood in Constantinople. Alexander consulted wizards about the comet to find out what it meant for him and his reign.

Further offending the clergy, Alexander took religious tapestries and silver candelabra from churches and used them to decorate chariot races in the Hippodrome.

The Patriarch Nicholas allowed him to get rid of his wife by sending her to a convent and marrying his mistress.

Unlike Leo, Alexander had absolutely no interest in high culture or leaving a legacy of laws and good governance. No writings of his survive or any record of speeches he made. Of course he only reigned for a year, perhaps he had no time to do so.

Alexander systematically rid himself of those who had been close to Leo VI, starting with the patriarch Euthymios; then his wife the empress Zoe. The Patriarch was insulted, abused, beaten, slapped around, and his beard was torn out. He remained silent and meekly endured the torture, knowing his suffering was a way to share in Christ's suffering. He was exiled and died shortly thereafter.

Alexander had two other brothers, Constantine had been his father's favorite and the second Stephen, had been castrated by their father, Basil I. What compelled Basil to castrate his son? When Leo became emperor in 866 he had his brother installed as Patriarch even though he was only 16. Surprisingly he seems to have been very religious and a success in his appointment.

Alexander had been spoiled by the luxuries of the palace and the flattery of courtiers. He was said to have been sexually debauched, licentious and immorally involved with dozens of women. He spent most of his free time hunting and playing polo. In his short reign of one year he made his polo buddy, John Lazares, rector of Hagia Sophia. The non-theological teachers of the Patriarchal School attached to Hagia Sophia were paid for by the emperor and he was involved in the selection process. The clergy were outraged when Lazares was killed playing polo at Hebdomon palace. Polo in Byzantium was a deadly sport. John died just a couple of months after his appointment and in the same year that Alexander died. John Lazares and Nicholas Mystikos were most likely responsible for this mosaic which would date it to 912. One wonders why it was placed in this out-of-the-way location in the North Gallery. The clergy would have been involved in the subject matter and design of mosaics that were set up in Hagia Sophia. They were a highly educated lot with a long tradition. Perhaps they are showing their dissatisfaction with Alexander by sticking him in a dark corner where no one could see him. Perhaps this was not the only one of him and there were others mosaics that have vanished.

Alexander would have seldom worn the Imperial vestments shown in the mosaic, but he started when he was young. These ornate and uncomfortable clothes were a part of the job of being a ruler. Although he must have felt like he was dressed up like a doll, these clothes impressed the people and were a sign of legitimacy. They were difficult in get in and out off and took special servants to dress you. In Hagia Sophia there were special chambers on the ground floor of the nave and in the galleries for changing. Before and after services - even during them; they could last hours - the emperor and his wife would use these vesting chambers to lighten the burden of these clothes and the regalia, taking items off, setting them aside and then putting them back on before they would emerge from the chambers. The Imperial family would also have a buffet here for breakfasting after liturgy. They would invite members of the court to join them.

These clothes would have been made of silk, heavily embroidered in gold thread and set with peals, enamels and gemstones. They were made in the Imperial workshops. There were two of them that made them; one tailored the dress in silk and the other would have applied the ornament. The more emperors there were at one time the more sets of vestments like these that would be required. Since emperors could be of different ages and sizes court officials would have had to had a number of sets available. They were actually lighter than they appear, because so much gold thread being used. There were two types of gold thread used. One was made of thin pure gold wire that was either used twisted around silk or linen thread or used without any thread. There was a second type made of flattened silver wire that was gilded; which was cheaper but it was heavier and could tarnish, requiring more attention to keep it clean and bright. These Imperial clothes were repaired, re-cut and recycled from reign to reign as needed and stored in special chambers near the palace.

Every co-emperor would need his own crown. There were Imperial workshops that made gold and jeweled things like diadems and chalices. They were the source of the famous Byzantine enamels. They made things not only for the court, but also treasures to be sent as gifts to foreign courts. One of the regular chores of the gold workshops was the maintenance and refurbishment of the crown jewels.

The image on the right shows how Alexander would have dressed from day-to-day. It is a silk kaftan and the form originated in the steppes of Central Asia where it was worn by horsemen. It was a versatile garment that was tailored to closely fit the wearer. The silk was a thick 6 strand twill weave called Samite. Each stand could be of a different color and worked into beautiful patterns. Kaftans like this were worn by Byzantine polo players.

The image on the right shows how Alexander would have dressed from day-to-day. It is a silk kaftan and the form originated in the steppes of Central Asia where it was worn by horsemen. It was a versatile garment that was tailored to closely fit the wearer. The silk was a thick 6 strand twill weave called Samite. Each stand could be of a different color and worked into beautiful patterns. Kaftans like this were worn by Byzantine polo players.

Alexander would have sent gifts of clothes made in the Imperial Tailor Workshop to generals in the field, foreign rulers, personal friends (including wives and mistresses) and other members of the aristocracy. They covered all types of clothes, hats , shoes and boots - even hand towels. The fine linen undergarments made there were especially esteemed. Clothes were made to different standards or quality, colors, patterns and value of the materials. Production in a year could be enormous. If an emperor wanted to show an exceptional level of honor he could send clothes from his own personal wardrobe. Alexis I Comnenus sent personal garments to Georgian nobility, which ended up be passed down as heirlooms by the family.

On 6 June Alexander bathed, dined, drank plenty of wine and when he had slept came down to play polo at Hebdomon. A pain arose in his entrails which had been overloaded with an excess of food and excessive drinking. He went back up into the palace bleeding profusely from his nose and his genitals; after one day he was dead after a 13 month reign. He was buried in Holy Apostles alongside his father, Basil I and his mother, Eudokia Ingerina, in a tomb of green verde antico marble.

Alexander also had four sisters; all of them were made nuns and sent to the convent of St. Euphemia.

Leo VI had a son, Constantine, who was only 6 when he died. He was crowned Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus - Born in the Purple - and co-reigned with Alexander for a year. When Alexander died the Patriarch Nicholas Mystikos became one of regents for Constantine.

Bob Atchison

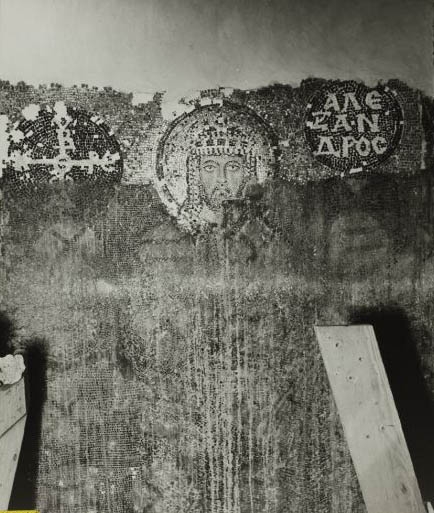

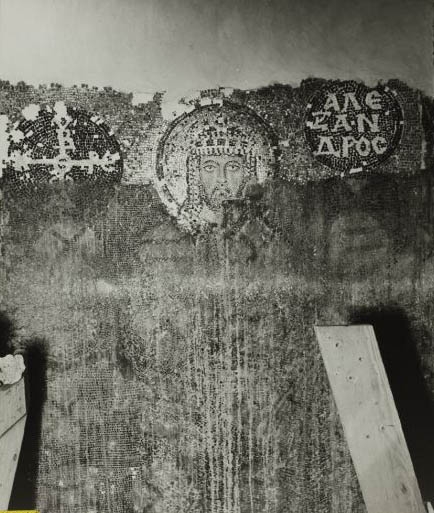

The following is from The Mosaics of Hagia Sophia at Istanbul: The Portrait of the Emperor Alexander: A Report on Work Done by the Byzantine Institute in 1959 and 1960 Paul A. Underwood and Ernest J. W. Hawkins. The photograph of the Alexander panel being uncovered is from the Robert Van Nice blog page.

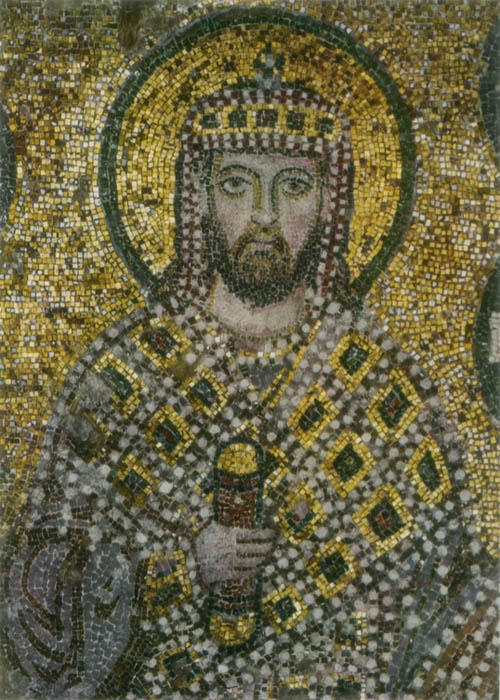

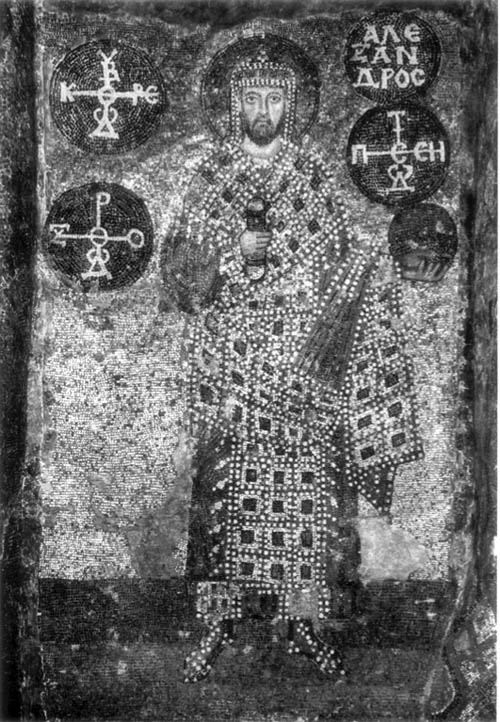

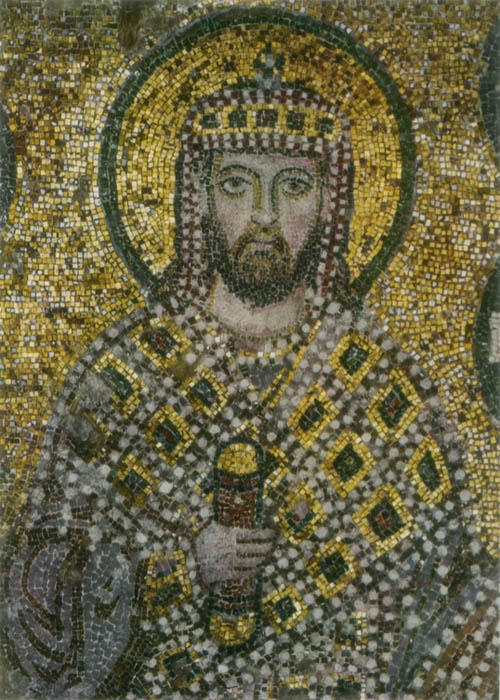

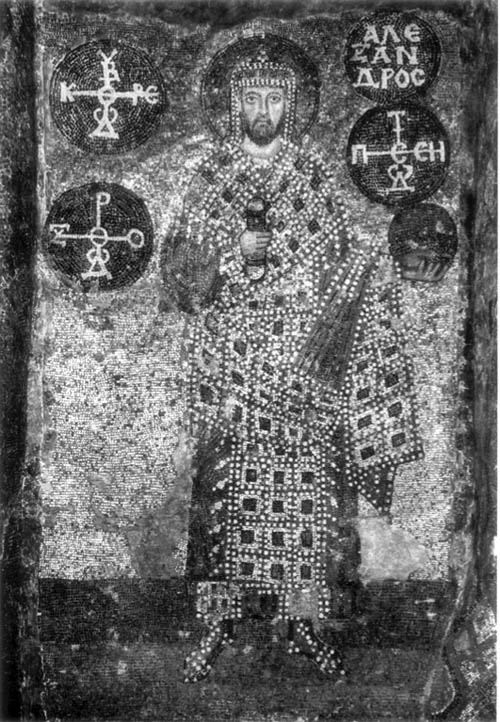

In contrast to the other imperial portraits in Hagia Sophia in which emperor and empress are depicted at each side of Christ or the Virgin, the Emperor Alexander stands alone within the narrow confines of the panel, a fact which accounts for the complete frontality of the figure. He is attired in ceremonial vestments and bears attributes in his hands that correspond rather closely to the trappings with which, according to the Book of Ceremonies, the emperors of the tenth century were equipped when they went in procession on Easter Sunday to Hagia Sophia for the services. It is said that on this occasion the emperors wore the sagion, a kind of tunic, which was bordered with golden embroideries, and the dark red skaramangion, which seems to have been put on over the sagion, for the tzizakion, which they wore up to that moment, was removed when the skaramangion was put on. The loros, a long and richly ornamented scarf, which was wound about the body, was then put on and either a white or a red crown, according to their preference, was placed on their head. Finally, a golden scepter adorned with gems and pearls was placed in their left hand and the akakia, or anexikakia, in their right.

In the mosaic all these elements of the costume with the exception of the scepter appear to be represented; instead of the scepter, Alexander holds the orb in his extended left hand, but in his right, as specified, he holds the akakia.

The undergarment (sagion) is visible only at the cuffs and hem which are, as the text described, richly embroidered and decorated with pearls. Over this is a loose-sleeved garment (skaramangion) of purple (dark red, according to the text) which is visible in the right sleeve and at the sides, from the knees downward; it is otherwise covered by the loros which is heavily decorated with gems and pearls. On his head he wears a red crown which is adorned with pearls and a golden circlet studded with gems. From the crown are suspended the perpendulia of pearls. On his feet he wears the imperial red boots, also decorated with pearls.

In the upper part of the panel, flanking the figure of the Emperor, are four inscribed discs, two on each side. The disc at the upper right presents the name of the Emperor in three lines. The other three contain cruciform monograms. The other extant portraits, if we exclude the coins on only portrait Alexander, which he appears, is in one of the miniatures of the manuscript of the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus in Paris (Bibl. Nat., gr. 510, fol. B) which depicts the Empress Eudocia Ingerina standing between the youthful figures of Leo VI on her right and Alexander, at about the age of ten, on her left.

In the upper part of the panel, flanking the figure of the Emperor, are four inscribed discs, two on each side. The disc at the upper right presents the name of the Emperor in three lines. The other three contain cruciform monograms. The other extant portraits, if we exclude the coins on only portrait Alexander, which he appears, is in one of the miniatures of the manuscript of the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus in Paris (Bibl. Nat., gr. 510, fol. B) which depicts the Empress Eudocia Ingerina standing between the youthful figures of Leo VI on her right and Alexander, at about the age of ten, on her left.

Another miniature of the same manuscript represents Basil I between the Prophet Elijah and the Archangel Gabriel. These portraits of the family of Basil I, though somewhat earlier, have very marked similarity to the mosaic in matters of costume and imperial attributes. The crowns are of the same type (low and tightly fitting, to conform to the shape of the head) with similar narrow circlets and similar perpendulia. Both Leo and Alexander hold the orb in their left hands and Leo, at least, also holds the akakia in his right hand. The only major difference between the vestments of the miniature portraits and the mosaic is in the loros. In the former the loros is always narrower, with three instead of four parallel rows of ornaments. There is, however, the same excessive use of pearls; the shoulders are outlined in pearls and from the edges of the loros pearl fringes are arranged in the same manner.

THE DATE OF THE ALEXANDER PORTRAIT

Alexander, the third son of Basil I, was born in A.D. 870 or 871. He was crowned as co-Emperor, at about the age of nine, before November of 879 and probably before August of that year, thus sharing the throne with his father and his elder brother Leo VI. He remained co-Emperor during Leo's life despite the hostility that existed between the brothers, and after Leo's death he ruled as sole Emperor for a period of thirteen months, from II May 912 until his death on 6 June 913, at which time, therefore, he must have been about forty-two or forty-three years of age. The mosaic portrait shows Alexander as a man of mature years and must, therefore, be ascribed to the late years of his life. It seems most probable, however, that it represents him in his capacity as sole Emperor and should be dated in the brief period of his reign. We incline to this conclusion by analogy to the other imperial panels in Hagia Sophia in which Constantine IX Monomachus, John II Comnenus, and his son and co-Emperor Alexius were depicted after their coronations. If this analogy applies also to the Alexander portrait, it would have been executed, in all probability, in 912.

It might be objected that in the portrait Alexander is called by the title of despot rather than basileus, the title used in the inscriptions of the later emperors portrayed in Hagia Sophia, and that he was, therefore, not the ruling emperor. The latter title, however, was conferred upon a co-emperor as well as upon a senior emperor just as the term despot, as we have seen, was used for both.

DESCRIPTION

The Background

The lower part of the background, which forms a ground zone in which the figure stands, is composed of three horizontal bands of green glass, each of a different value and character, the darkest at the top and the lightest at the bottom. The uppermost band consists primarily of emerald green tesserae, the middle band of pea green, and the lower one mainly of yellow-greens.

Above the ground zone, the background is laid in horizontal rows of gold and silver tesserae which are set normal to the plane of the panel; the rows are far from straight and are rather widely separated. The proportion of silver to gold is about 2 to 5, or about 30 per cent silver. Only in the ground of the nimbus and a few other areas is gold used without an admixture of silver. The plaster setting bed in which the metallic cubes are laid had been painted yellow ochre before the tesserae were inserted.

The Face

The areas of flesh in the face and neck are set in three colors of the usual (Tunisian?) marble: white, warm off-white, and pink. Pale green glasses are used for the shading of the face and neck. Across the brow, the edge of the lining or padding of the crown is indicated by short diagonal strokes of pale yellow-green glass alternating with black-violet glass and the purple cartoon paint on small patches of unset plaster. The shadow is then drawn by the black-violet line that forms part of the outlining of the face.

The eyebrows are drawn in black and violet glass tesserae and the shadow lines beneath are of pale green-umber glass. The upper eyelids are in off-white marble, the eyelashes and pupils in black. The whites of the eyes are of white marble at the left sides of the eyeballs and of bluish gray Proconnesian marble at the right. The irises were left unset in the cartoon paint of light brown. The lower eyelids are in pale violet glass and the shadow lines below in pale yellow-green glass.

The ridge and tip of the nose are white marble with a line of off-white marble at the left side. At the right side of the nose are three lines: the inner line, beside the ridge, in pink marble; the middle line, which continues the line of the eyebrow, in pale violet glass; and the outer line in light green glass. The shading of the nose at the left, is done in two lines of yellow-green and one of light green glass adjoining the ridge. The tip of the nose is highlighted by a large polygonal stone of white. The shadows beneath the nostrils are violet glass and a rather large square violet tessera marks the shadow below the point of the nose above the lips. The surrounding shadows are in pale green and yellow-green glasses. Each of the lips is drawn by a single row of pink marble with the shadow between them in pale violet glass.

The ridge and tip of the nose are white marble with a line of off-white marble at the left side. At the right side of the nose are three lines: the inner line, beside the ridge, in pink marble; the middle line, which continues the line of the eyebrow, in pale violet glass; and the outer line in light green glass. The shading of the nose at the left, is done in two lines of yellow-green and one of light green glass adjoining the ridge. The tip of the nose is highlighted by a large polygonal stone of white. The shadows beneath the nostrils are violet glass and a rather large square violet tessera marks the shadow below the point of the nose above the lips. The surrounding shadows are in pale green and yellow-green glasses. Each of the lips is drawn by a single row of pink marble with the shadow between them in pale violet glass.

The beard is of violet and black glasses lighted with yellow-green glass. Here and there the unset cartoon paint of purple and green is to be seen.

The Nimbus

The nimbus is outlined with two rows of emerald green glass tesserae; the field is of gold tesserae set in concentric circles except for the two innermost rows which follow the contour of the crown. This manner of setting and the fact that no silver tesserae are used serve to differentiate the nimbus from its surroundings and give it a warm brownish tone that is markedly different from the paler color of the background.

The Right Hand and the Akakia

The right hand, which clasps the akakia, is outlined with a row of red glass and filled with marbles: pink on the lower sides of the fingers and back of the hand, and off-white on the upper sides. The tip of the thumb protruding from behind the right side of the akakia, above the clenched fingers, was set with only a single tessera which is of silver and is laid in reverse. The outline of the tip of the thumb is the cartoon drawing in purple paint.

The akakia, which was probably a small pouch of silk filled with dust and wrapped in a purple kerchief, is represented as being cylindrical in form, with rounded ends. It is outlined in violet-black glass, its rounded top and bottom are of gold tesserae, and the kerchief is represented in red glass. Two horizontal rows of violet-black glass, separated by a row of red glass, border the edges of the kerchief.

The Left Hand and the Orb

The left hand, held out to one side, balances the orb. The outline of the orb is a single row of the same dark blue glass that is used to fill the field of the lower half; the upper half is filled with emerald green glass. The division between the two halves is not a straight line but a double curve that dips downward in the center.

Only the four fingers and the back of the hand that were exposed to view in front of the orb are set in mosaic tesserae. The thumb and palm of the hand, as though seen through the orb, which is indicated, therefore, as being trans- parent, are left in the unset plaster of the setting bed, painted here in terra verte and purple which are blended in places. Six red glass tesserae indicate the left edge of the little finger; two widely spaced red glass tesserae are set at the right edge of the index finger; and three are placed along the under side of the thumb. Six tesserae of pink marble continue the line below the thumb and another six describe the ball of the thumb against the palm. The under side of the hand and fingers are sparsely set with pink and white marble. Otherwise the outline of the hand is left mostly in the purple cartoon paint and the thumb and ball of the thumb are in terra verte.

Only the four fingers and the back of the hand that were exposed to view in front of the orb are set in mosaic tesserae. The thumb and palm of the hand, as though seen through the orb, which is indicated, therefore, as being trans- parent, are left in the unset plaster of the setting bed, painted here in terra verte and purple which are blended in places. Six red glass tesserae indicate the left edge of the little finger; two widely spaced red glass tesserae are set at the right edge of the index finger; and three are placed along the under side of the thumb. Six tesserae of pink marble continue the line below the thumb and another six describe the ball of the thumb against the palm. The under side of the hand and fingers are sparsely set with pink and white marble. Otherwise the outline of the hand is left mostly in the purple cartoon paint and the thumb and ball of the thumb are in terra verte.

The Imperial Vestments

The crown is basically red but is heavily encrusted with pearls and a golden circlet studded with jewels. It is divided horizontally into three zones. At the top and bottom are two rows of tesserae of alternating red glass and the dense mat-white rock with which pearls are represented. Between these two zones is a circlet of gold in which five square jewels are set. That at the center is of red glass shadowed by the pale amber of gold tesserae which have been set on one side or in reverse. The others are of emerald green glass shadowed by dark blue. A row of black-violet glass tesserae defines the top of the crown on which stands a cross of emerald green glass tesserae with a pearl at the center and three at the base. The perpendulia, which are attached to each side of the crown, fall in straight lines down each side of the face to the shoulders. Each is composed of two strands of alternate red glass and matte-white representing pearls. The outermost strand on each side appears to be attached to the upper band of pearls set in the crown, while the innermost attach to the lower band.

The long undergarment (sagion?), visible only at the richly decorated cuffs and hem, was worn beneath an outer garment, and like the outer garment, it appears to have been of purple, as is indicated by the background on which the embroidered and encrusted ornaments are worked. The purple is rendered in tesserae that are chips of a light purple local stone.31At the hem, the under- garment is decorated with two vertical bands of gold, above the feet, in which four rectangular jewels, rendered in green and red glass, are set. The bands are bordered at the sides by double rows of pearls and below by a single row. The jeweled band at the right has lost the tesserae with which it was set. Between the two bands, and again at the far right, are three vertical double rows of pale greens and ambers, in indication of folds, which are in reality metallic cubes set on one side or in reverse. The cuff of the garment's right sleeve is of gold with two rectangular jewels, one of green glass and the other of large red tesserae of terracotta. Along the very end of the cuff, next to the hand, is a single row of pearls. The tesserae of the left cuff, at the far right, have fallen, except for a border of pearls at the wrist similar to that of the right cuff. In all probability the two cuffs were originally alike.

The outer garment (skaramangion?), covered in very large part by the loros, is visible in the wide sleeve, at the left, and over the lower legs at both sides of the lower end of the loros which is suspended down the center of the figure. In these areas it is not decorated and is indicated as a purple garment by the use of the same pale purple local stone, mentioned above, that was the basic material of the undergarment. The outline drawing and the folds of the outer garment are indicated by single, double, or triple rows of metallic tesserae set in reverse or on one side to produce a brown amber color. In a small V-shaped area at the neck, the garment was bordered at the neck line by a row of alternating pearls and red glass tesserae, like the strands of the perpendulia; this is separated by a single row of gold from another row of pearls which alternate with metallic cubes set on one side or in reverse. This border has suffered losses.

Wrapped about the body of the Emperor is the unusually broad and heavy loros. This long scarf, with one end hanging at the same level as the bottom of the outer garment, extends vertically up the front of the figure and seems to have been passed over the right shoulder whence it presumably continues down the back of that shoulder to emerge under the right arm and then pass upward over the left shoulder. It then seems to have been drawn diagonally across the back and brought forward around the right hip to fall diagonally across the front where it is folded to reveal the back, or lining, of the scarf as it is draped upward over the extended right arm. Finally, the end of the loros falls over the left wrist and hangs in a vertical fold with its ornamented face exposed to view. The edges of the loros are bordered, and the field divided into squares, by double rows of pearls. The rows of pearls, as also the individual pearls in each row, are separated by metallic tesserae set in reverse or on one side. The tesserae of these borders are rather widely spaced, and it can be seen that the setting bed is painted a light purple color. Within each of the squares into which it is thus divided is a large square jewel surrounded by one, two, or three rows of metallic tesserae; in the upper parts of the figure these are entirely of gold, but in the lower part a few silver tesserae are here and there inserted. The jewels are alternately red and green glass outlined by a single row of blue glass, with the exception of the vertical row of three jewels at the far left under the sleeve and the jewel under the cuff at the left, which are composed of terracotta. These exceptions are, however, also outlined with blue glass. The jewels in the loros are so arranged that the red and green colors alternate in both the longitudinal and transverse directions on the scarf. Along each side of the loros is a kind of fringe

consisting of widely separated sprays of three pearls that are attached at intervals to the edges. Some of these, along the lower, vertical, part of the loros, have large pear shaped pearls, of from nine to eleven tesserae, which are placed at the centers of the sprays.

The boots are outlined by one, two, and in some places three, rows of red glass with a few interspersed tesserae of amber or green color which are metallic cubes set in reverse or on one side. The lighter areas of the boots are of terracotta. Intermingled with these materials, as decoration, are a number of round mat-white stones representing pearls.

The Inscribed Discs

The backgrounds of the four inscribed discs which flank the upper parts of the figure are set in dark blue glass; in the inscribed disc at the lower right the rows are horizontal, in the others, concentric. The inscriptions are made of the same dense mat-white rock with which pearls are indicated. The individual letters are fairly consistently outlined by single rows of the dark blue of the background.

TECHNICAL DETAILS

As margins at the two sides of the panel, the setting bed was left exposed in two narrow strips averaging about 5 cm. in width. While much of this plaster along the left side of the panel was lost and had to be replaced, that along the right side was in great part preserved and is a dark gray. In conformity with almost invariable practice, the contours of all parts of the figure were bordered with one or, more usually, two rows of the materials with which the surrounding background was to be set. Throughout most of the contours that were to be relieved against the gold and silver background, it is evident that the rows of the metallic tesserae that follow the contours were set along with the figure itself, before the plaster setting bed for the metallic background had been applied. This is most clearly evident along the left edge of the figure from the top of the green ground zone to the projecting sleeve of the figure. In the area of lost background tesserae at the level of the knee on this side, and again at the hip, the line of juncture between the two applications of plaster setting bed is clearly visible, and in some other places where the mosaic is intact the juncture of the two has opened up slightly and can be traced on close examination. In the contours that occur in the green zone at the bottom of the panel, however, slightly open joints occur here and there between the very edge of the figure itself and the surrounding row, or rows, of green glass which parallel the contours, thus indicating that none of the background material was set here along with the figure. This is clearly observable along the right side of the hem of the garment and the right side of the foot at the right. These phenomena indicate the limits of various stages of the work in the construction of the mosaic.

Alexander I, a handsome Byzantine playboy and polo player with thick blond hair to his shoulders and beard, was co-emperor with his

Alexander I, a handsome Byzantine playboy and polo player with thick blond hair to his shoulders and beard, was co-emperor with his  After Leo died Alexander reigned as sole Emperor for only a year 912-913. It is worth noting that Halley's Comet appeared that year and was seen as an omen of blood in Constantinople. Alexander consulted wizards about the comet to find out what it meant for him and his reign.

After Leo died Alexander reigned as sole Emperor for only a year 912-913. It is worth noting that Halley's Comet appeared that year and was seen as an omen of blood in Constantinople. Alexander consulted wizards about the comet to find out what it meant for him and his reign. The image on the right shows how Alexander would have dressed from day-to-day. It is a silk kaftan and the form originated in the steppes of Central Asia where it was worn by horsemen. It was a versatile garment that was tailored to closely fit the wearer. The silk was a thick 6 strand twill weave called Samite. Each stand could be of a different color and worked into beautiful patterns. Kaftans like this were worn by Byzantine polo players.

The image on the right shows how Alexander would have dressed from day-to-day. It is a silk kaftan and the form originated in the steppes of Central Asia where it was worn by horsemen. It was a versatile garment that was tailored to closely fit the wearer. The silk was a thick 6 strand twill weave called Samite. Each stand could be of a different color and worked into beautiful patterns. Kaftans like this were worn by Byzantine polo players.

In the upper part of the panel, flanking the figure of the Emperor, are four inscribed discs, two on each side. The disc at the upper right presents the name of the Emperor in three lines. The other three contain cruciform monograms. The other extant portraits, if we exclude the coins on only portrait Alexander, which he appears, is in one of the miniatures of the manuscript of the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus in Paris (Bibl. Nat., gr. 510, fol. B) which depicts the Empress Eudocia Ingerina standing between the youthful figures of Leo VI on her right and Alexander, at about the age of ten, on her left.

In the upper part of the panel, flanking the figure of the Emperor, are four inscribed discs, two on each side. The disc at the upper right presents the name of the Emperor in three lines. The other three contain cruciform monograms. The other extant portraits, if we exclude the coins on only portrait Alexander, which he appears, is in one of the miniatures of the manuscript of the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus in Paris (Bibl. Nat., gr. 510, fol. B) which depicts the Empress Eudocia Ingerina standing between the youthful figures of Leo VI on her right and Alexander, at about the age of ten, on her left.

The ridge and tip of the nose are white marble with a line of off-white marble at the left side. At the right side of the nose are three lines: the inner line, beside the ridge, in pink marble; the middle line, which continues the line of the eyebrow, in pale violet glass; and the outer line in light green glass. The shading of the nose at the left, is done in two lines of yellow-green and one of light green glass adjoining the ridge. The tip of the nose is highlighted by a large polygonal stone of white. The shadows beneath the nostrils are violet glass and a rather large square violet tessera marks the shadow below the point of the nose above the lips. The surrounding shadows are in pale green and yellow-green glasses. Each of the lips is drawn by a single row of pink marble with the shadow between them in pale violet glass.

The ridge and tip of the nose are white marble with a line of off-white marble at the left side. At the right side of the nose are three lines: the inner line, beside the ridge, in pink marble; the middle line, which continues the line of the eyebrow, in pale violet glass; and the outer line in light green glass. The shading of the nose at the left, is done in two lines of yellow-green and one of light green glass adjoining the ridge. The tip of the nose is highlighted by a large polygonal stone of white. The shadows beneath the nostrils are violet glass and a rather large square violet tessera marks the shadow below the point of the nose above the lips. The surrounding shadows are in pale green and yellow-green glasses. Each of the lips is drawn by a single row of pink marble with the shadow between them in pale violet glass. Only the four fingers and the back of the hand that were exposed to view in front of the orb are set in mosaic tesserae. The thumb and palm of the hand, as though seen through the orb, which is indicated, therefore, as being trans- parent, are left in the unset plaster of the setting bed, painted here in terra verte and purple which are blended in places. Six red glass tesserae indicate the left edge of the little finger; two widely spaced red glass tesserae are set at the right edge of the index finger; and three are placed along the under side of the thumb. Six tesserae of pink marble continue the line below the thumb and another six describe the ball of the thumb against the palm. The under side of the hand and fingers are sparsely set with pink and white marble. Otherwise the outline of the hand is left mostly in the purple cartoon paint and the thumb and ball of the thumb are in terra verte.

Only the four fingers and the back of the hand that were exposed to view in front of the orb are set in mosaic tesserae. The thumb and palm of the hand, as though seen through the orb, which is indicated, therefore, as being trans- parent, are left in the unset plaster of the setting bed, painted here in terra verte and purple which are blended in places. Six red glass tesserae indicate the left edge of the little finger; two widely spaced red glass tesserae are set at the right edge of the index finger; and three are placed along the under side of the thumb. Six tesserae of pink marble continue the line below the thumb and another six describe the ball of the thumb against the palm. The under side of the hand and fingers are sparsely set with pink and white marble. Otherwise the outline of the hand is left mostly in the purple cartoon paint and the thumb and ball of the thumb are in terra verte.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints