Andronikos I Komnenos - Revolts and Seizes Power From Alexios II and Maria of Antioch

From O City of Byzantium by Niketas Choniates

While at Oinaion, he heard of Manuel's death and received detailed information of the disorders within the palace, how Emperor Alexios entertained himself with horse races and was given to amusements in which childish minds delight, how some of his noble guardians, like bees, frequently winged their way to the provinces and stored up money as though it were honey while others, like goats, craved after the young shoot of the empire and continually desired to gain possession of it; still others, emulating hogs, fattened themselves on the most sordid revenues and, choosing not to lift their heads and look at anything laudable or beneficial for the common fatherland, rolled about in their filthy deeds, rooting like swine after every evil gain.

While at Oinaion, he heard of Manuel's death and received detailed information of the disorders within the palace, how Emperor Alexios entertained himself with horse races and was given to amusements in which childish minds delight, how some of his noble guardians, like bees, frequently winged their way to the provinces and stored up money as though it were honey while others, like goats, craved after the young shoot of the empire and continually desired to gain possession of it; still others, emulating hogs, fattened themselves on the most sordid revenues and, choosing not to lift their heads and look at anything laudable or beneficial for the common fatherland, rolled about in their filthy deeds, rooting like swine after every evil gain.

Andronikos searched very meticulously and thoroughly to find an opportune and plausible excuse for seizing the throne. After much thought, and after contriving every possible scheme, he finally came upon the written oath he had sworn to Manuel and his son Alexios. There he found inserted among the others the following clause (he was bound not to distort the words by false interpretations but to take them at face value): "And should I see or perceive or hear anything bringing dishonor to you or inflicting injury to your crown, I shall relay this information to you and thwart any such attempt as far as I am able."

Brooding on these words like a fly on an open wound, he found them extremely useful for achieving the despotic rule for which he had so long been laboring, the rule due him for his dignified bearing and commanding disposition. He sent successive letters to his nephew Emperor Alexios, to the patriarch Theodosios, and to the remaining devoted friends of the deceased Emperor Manuel, relating his distress over the ugly gossip and professing his indignation lest the protosebastos should not be removed from control over the throne and relegated to a lesser rank, not only because of the approaching, indeed, the already manifest, destruction of Emperor Alexios from that quarter but above all also for the unseemly and unacceptable rumor to gentle ears being proclaimed from the wall

tops and lying in wait at the gates of princes and being echoed throughout the universe.' Expressing and writing these things with great conviction and charm (for he was, if anything, well versed in letter writing, ever quoting from the Epistles of Paul, the orator par excellence of the Holy Spirit), he won everyone to his views so that they concurred that he was the only true friend of the Romans who, over a long period of time and because of his hoary experience, had carried off the highest prizes.

Andronikos left Oinaion and made his way toward the queen of cities. On the way, he administered his own oath to whomever he met and explained the reason for his revolt to those who questioned him. Those who nurtured a desire to overthrow the government were eager to believe the ancient prophecy that Andronikos would some day reign as emperor; they swarmed about him excitedly like jackdaws around a soaring eagle with crooked talons. Thus did the Paphlagonian faction behave toward him as he made his way, receiving him with great honor as though he were a savior sent from heaven.

The protosebastos Alexios raged furiously; confident of his own power and his great influence over the empress, he was like the serpent which, having fed on an abundance of evil herbs, is terrible to look upon. Nothing whatsoever could be done except through him. And if someone accomplished something in secret by begging a favor from the empress or by having his petition granted while the emperor was engrossed in playing with nuts or casting pebbles, even this did not escape his attention. To assure that the accomplishments of others would be returned to him for review like the whirl of eddying waters, he had the emperor promulgate a decree that henceforth no document signed by the imperial hand would be valid unless first reviewed by Alexios and validated by his notation "approved" in frog green ink. He made his moves freely as though playing a game of draughts, and all the revenues which had been collected with much sweat by the preceding Komnenian emperors who, I might add, stripped even the indigent, were channeled to the protosebastos and the empress; and that was fulfilled which Archilochos plainly wrote, that what has been amassed at the expense of much time and labor often flows into the belly of the whore.

Henceforth, the entire City looked to Andronikos, and his arrival was regarded as a beacon and bright shining star in the moonless night. The mighty and the powerful encouraged Andronikos by dispatching letters in secret to hasten his entry, telling him that there was no one to oppose him or even to obstruct his shadow, and that they were waiting to receive him with open arms and to take him readily to the heart.

Henceforth, the entire City looked to Andronikos, and his arrival was regarded as a beacon and bright shining star in the moonless night. The mighty and the powerful encouraged Andronikos by dispatching letters in secret to hasten his entry, telling him that there was no one to oppose him or even to obstruct his shadow, and that they were waiting to receive him with open arms and to take him readily to the heart.

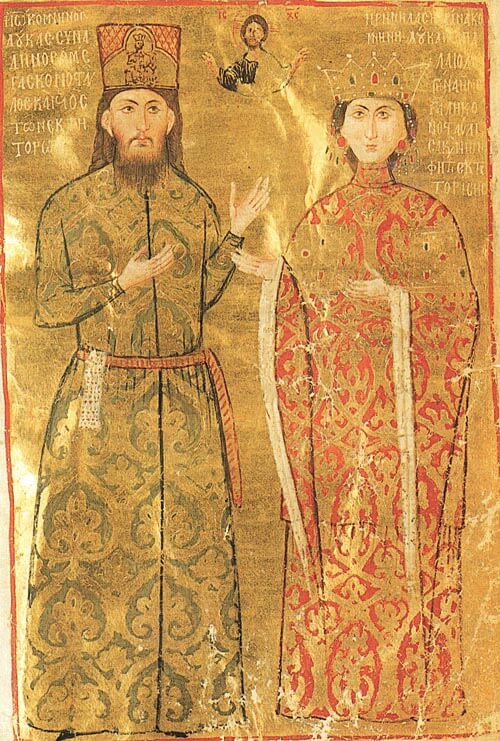

It was preeminently the porphyrogenita Maria, Emperor Alexios's half-sister, who, together with the kaisar, her Italian husband [Renier], encouraged Andronikos to step forth bravely. Maria nearly choked with rage at the thought of the protosebastos wickedly cavorting in the paternal marriage bed. Reckless and masculine in her resolution, by nature exceedingly jealous of her stepmother, and unable to endure that she had been bested and was held suspect as a rival, Maria dispatched letters to Andronikos prodding him like a horse at the starting gate anxious to run the race, delighting in the evil joy of her own making and bringing on her own ruin. Unable to conceal her hatred for the protosebastos, she opposed him openly and never ceased from plotting to do him injury.

She won over to her side several of her kinsmen, in particular those whom she knew to side with Andronikos and to be hostile to the protosebastos (these were Alexios Komnenos, begotten of Emperor Manuel through his niece Theodora; Andronikos Lapardas; Andronikos's two sons, John and Manuel; the eparch of the City, John Kamateros; and many others). Conspiring to confirm the oath of allegiance to her brother and emperor while endorsing the death of the protosebastos, she awaited the opportune moment for his overthrow.

She won over to her side several of her kinsmen, in particular those whom she knew to side with Andronikos and to be hostile to the protosebastos (these were Alexios Komnenos, begotten of Emperor Manuel through his niece Theodora; Andronikos Lapardas; Andronikos's two sons, John and Manuel; the eparch of the City, John Kamateros; and many others). Conspiring to confirm the oath of allegiance to her brother and emperor while endorsing the death of the protosebastos, she awaited the opportune moment for his overthrow.

She deemed that the appropriate occasion would be the procession of the protosebastos, together with the emperor, to Bathys Ryax [Deep Stream] to perform the sacred rites pertaining to Theodore, the Martyr of Christ, on the seventh day of the first week of Lent [7 February 1181]. Thus she made preparations for the undertaking and suborned ti, the cutthroats of her opponent to lay bare the murderous knife, but because of an unexpected turn of events, she was thwarted in her plot. When both the deliberation and the plot were exposed a short time afterwards [1 March 1181], the conspirators were brought before the imperial tribunal. The trial, although conducted pro forma, was not based on the determination of the facts; the sentence followed immediately, and the accused were carried off to prison like speechless fishes without being given the right to answer the charges.

The porphyrogenita fled with her husband to the Great Church [before Easter, 5 April 1181], asserting that she was escaping her exceedingly wrathful stepmother and her violent lover. Not only did she excite the pity of the patriarch and the clergy but she also moved the majority of the promiscuous rabble to such a degree that they very nearly shed tears over her. A good portion of the indigent populace was angry on her account because she had plied them with gifts of copper coins, thereby inciting them to rebellion and showing contempt for the special privileges accorded those who seek asylum. Thus she took new courage, and when she was offered amnesty for her crimes, she turned a deaf ear and also demanded a new trial for her fellow conspirators and their release from prison. She could not bear that the protosebastos should be in control of the administration of public affairs and asserted that he had transgressed and offended against the law and, in consequence, had sullied the dynasty. She insisted, furthermore, that he be ejected from the palace and uprooted for causing the emperor's ruination like a tare growing along- side the noble plant and choking the wheat.

She openly pursued ends that were not to be realized. The protosebastos clung to the palace apartments like an octopus clamping its suckers on a rock. And when her brother, the emperor, threatened to evict his sister the kaisarissa from the temple by force if she did not voluntarily remove herself from the sacred precincts (by saying emperor, I mean that the demands were made by the protosebastos and the emperor's mother), she replied that she would never depart of her own free will.

Fearful lest she be seized and arrested, Maria stationed guards at the church's portals and posted sentries at the entranceways, converting the house of prayer into a den of thieves or a well-fortified and precipitous stronghold, impregnable to assault. Her actions became more and more reprehensible. She enlisted mercenaries and transformed the sacred courtyard into a military camp. Italians in heavy armor and stouthearted Iberians from the East who had come to the City for commercial purposes were recruited, as was an armed Roman phalanx, and all the while Maria paid no heed to those who exhorted her to sue for peace, nor did she give way to the patriarch himself, who pressed her vehemently to the point of becoming exceeding wrathful, often censuring her in a passion.

The entire populace from the other side of the City rejoiced without reason and could not be constrained. The excessively tumultuous rabble of Constantinople, which rejoiced in rashness and was perverse in its ways, was comprised of diverse races, and one could say that it was as fickle in its views as its trades were varied. And since it has ever been the normal course of events for the worst cause to triumph, and for people to seek the single sweet grape among many sour ones, the rabble is impelled by no reason whatsoever, nor does it take precautions to restrain agitators. At times disposed to sedition on the basis of mere rumor, it is more destructive than fire, throwing itself, so to speak, against drawn swords and senselessly resisting projecting headlands and the soundless swell, while, at other times, cowering in fear at every noise, it bends its neck so that whosoever desires may trample upon it. It was fairly accused of inconstancy of disposition and of being extremely untrustworthy. Neither were the inhabitants of Constantinople ever observed doing what was best for themselves, no did they heed others who proposed measures for the common good, and they were forever resentful of those cities flourishing nearby which, safeguarded by land and sea, distributed and poured out their goods in abundance to other cities of foreign nations. Their indifference to the authorities was preserved as though it were an innate evil; him whom today they extol as an upright and just ruler, tomorrow they will disparage as a malefactor, thus displaying in both instances their lack of judgment and inflammable temperament.

The entire populace from the other side of the City rejoiced without reason and could not be constrained. The excessively tumultuous rabble of Constantinople, which rejoiced in rashness and was perverse in its ways, was comprised of diverse races, and one could say that it was as fickle in its views as its trades were varied. And since it has ever been the normal course of events for the worst cause to triumph, and for people to seek the single sweet grape among many sour ones, the rabble is impelled by no reason whatsoever, nor does it take precautions to restrain agitators. At times disposed to sedition on the basis of mere rumor, it is more destructive than fire, throwing itself, so to speak, against drawn swords and senselessly resisting projecting headlands and the soundless swell, while, at other times, cowering in fear at every noise, it bends its neck so that whosoever desires may trample upon it. It was fairly accused of inconstancy of disposition and of being extremely untrustworthy. Neither were the inhabitants of Constantinople ever observed doing what was best for themselves, no did they heed others who proposed measures for the common good, and they were forever resentful of those cities flourishing nearby which, safeguarded by land and sea, distributed and poured out their goods in abundance to other cities of foreign nations. Their indifference to the authorities was preserved as though it were an innate evil; him whom today they extol as an upright and just ruler, tomorrow they will disparage as a malefactor, thus displaying in both instances their lack of judgment and inflammable temperament.

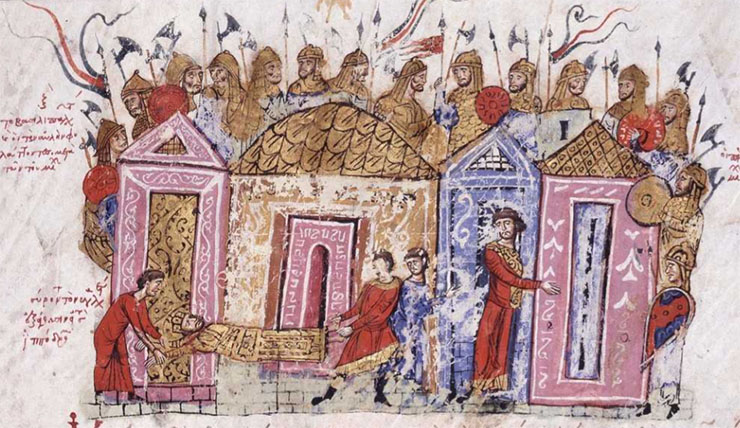

It was under these circumstances that there was a muster of forces assembled into military companies. At first they openly defended the porphyrogenita Maria, ostensibly taking pity on her as suffering undeservedly; then they inveighed against the protosebastos for behaving badly without cause and for abusing his good fortune; finally, they were vexed at the emperor's mother. Gradually they rose up in open revolt. Three priests, one bearing an image of Christ in relief into the forum, and another taking up and carrying a cross on his shoulder, and a third waving a sacred banner in the breeze, drew on the seditionists as milk draws flies. Responding as though to a prearranged signal, they shouted acclamations in praise of the emperor (this, indeed, is the sure sign of those moving to sedition; beginning with the best of principles their end is revolution) and subjected the protosebastos and the empress to anathema. They did not confine these activities only to the vicinity of the Milion but also gathered at the turning post of the magnificent Hippodrome while they faced the palace. When this was repeated over many days, the populace was incited to open rebellion. In a rage, many willfully pulled down the most splendid dwellings and plundered their furnishings while the protosebastos and the empress looked on with remarkable sang-froid. Among these was the very beautiful residence of Theodore Pantechnes, the eparch of the City, who presided over the probate court, distinguished himself on the judge's bench, and saved his own life by taking flight. The mob carried off everything within, even the public law codes containing those measures which pertained to the common good of all or to the majority of citizens; these were powerless before the craving for private gain and could not wet the winebibber's pharynx.

Seeing that matters were going from bad to worse, the supporters of the protosebastos decided to take counsel as to how to stave off ruin. Since they could not see the kaisarissa Maria changing her mind in any way or moderating her excessive demands, they decided to move against her with a military force and to drive her out of the holy temple as from some bulwark.

Seeing that matters were going from bad to worse, the supporters of the protosebastos decided to take counsel as to how to stave off ruin. Since they could not see the kaisarissa Maria changing her mind in any way or moderating her excessive demands, they decided to move against her with a military force and to drive her out of the holy temple as from some bulwark.

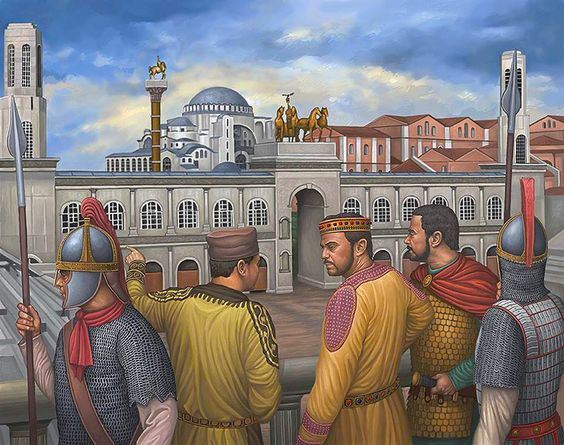

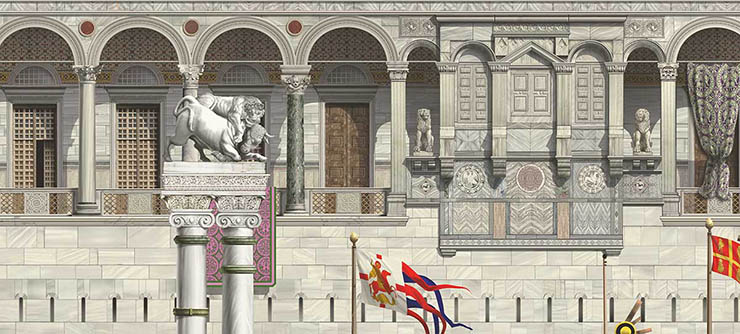

Not a few troops were assembled from both the eastern and western divisions and brought together into one camp at the Great Palace, and a reconnaisance was undertaken to determine an advantageous position whence to launch an assault upon the church while the kaisarissa deployed her troops in her desire to decide the contest in her favor. All the dwellings adjacent to Hagia Sophia and adjoining the Augousteon were demolished by her men, and they ascended the great triumphal arch which stands in the Milion and prepared to offer resistance to the imperial troops. Soldiers entered the Church of St. Alexios, which bordered on the courtyard of the Augousteon, and stood guard.

On the seventh day [Saturday], the second of May in the fifteenth indiction [1181], the imperial troops, bounding from the palace at dawn, entered first the church of John the Theologian, also called Diipeion, under their commander, a certain Sabbatios, an Armenian. Afterwards they appeared on the roof of the church and let out unintelligible cries. When the time for battle was at hand and the forum was especially full about the third hour of the day [9:00 A.M.], they inflicted no little injury on the kaisarissa's troops who fought from the triumphal arch of the Milion and the church of Alexios to take the advantage of fighting from above, hurling down their arrows like thunderbolts from on high. Other well-equipped contingents issued forth from the palace, filled the streets, and occupied the lanes leading to the Great Church, so that the populace was prevented from giving aid to the kaisarissa, as all approaches were cut off by men-at-arms. Her own troops sallied forth from the temple, crossed over the open court of the Augousteon, and engaged the imperial forces in the streets; a few contending against many, they were soon exhausted and their courage sapped.

The struggle was keenly contested, with the discharge of arrows and hotly disputed hand-to-hand combat. The moaning of the smitten and the cheering on of those spilling blood could be heard on both sides. Until high noon the battle was evenly matched, and Victory, undecided, balanced the scales equally, favoring one side and then the other, but towards sundown, she clearly favored the imperial troops. Maria's men were driven from the church, pushed from the streets into the Augousteon, and shut in, trapped inside, while those standing upon the arches of the Milion and fighting from the church of Alexios took flight. Once the imperial troops had taken possession of these positions, they fixed the standards portraying the imperial family above the arches, and the gates of the Augousteon were shattered by the axe and the stonecutter's tool. The kaisarissa's troops, bombarded by the enemy from the top of the arches, were no longer able to resist and suffered heavy casualties in hand-to-hand combat with those soldiers who had poured into the open court of the Augousteon. They slowly stole away, protected for a time by the stone missiles and arrows discharged by the defenders positioned above the gallery of the Catechumeneia (also called the Makron), which faced in the direction of the Augousteon and the building of Thomaites. Finally, the troops from the church, hard pressed by those smiting them from all sides, withdrew from the open court of the Augousteon.

"Nor should you regard it an unholy act to defend yourselves and (entered the outer narthex which displays the exquisite mosaic of the very 'first and greatest of the archangels serving God [Michael] with sword drawn, standing guard over the temple." Consequently, the imperial troops could not advance any further in fear of the temple's narrow passageways or could the kaisarissa's exhausted soldiers exit to give battle.

"Nor should you regard it an unholy act to defend yourselves and (entered the outer narthex which displays the exquisite mosaic of the very 'first and greatest of the archangels serving God [Michael] with sword drawn, standing guard over the temple." Consequently, the imperial troops could not advance any further in fear of the temple's narrow passageways or could the kaisarissa's exhausted soldiers exit to give battle.

The kaisar was afraid that he and his wife might be apprehended ignobly by their adversaries, and the patriarch was anxious lest the enemy troops enter the temple, with unholy feet trample the holy floor, and with hands defiled and dripping with blood still warm plunder the all-holy dedicatory offerings. Thus, the patriarch donned his pontifical vestments and took the Holy Gospels in his hand, and all three descended to the proskenion [outer narthex] of the temple, also called the Protekdikeion, where the troops fighting on behalf of the kaisarissa had lodged after their flight. The kaisar assembled the men-at-arms who guarded the entrances of the church and those of his Latin bodyguard who were still unscathed, as well as his wife's servants, all told about one hundred in number. He stood on a raised bench located at the Makron in the midst of his troops ready for battle and said the following:

It had been better had we donned our armor and taken up the sword against the enemies of the cross and not against compatriots and coreligionists; it is because they have badly mismanaged the affairs of the Roman empire that they must be removed, and it is by necessity and not by choice that we have sharpened our lances against them. Let us bravely oppose our assailants and reflect not that we are of the same race and religion but look upon them first as enemies of God whose holy temple they enter without shame, and then let us avenge ourselves against our adversaries. Moreover, we cannot be held responsible for the need to defend ourselves. Even though we did not give offence to them or take up arms against them, they came against us brazenly as though we had been set forth last, as it were appointed to death; they trample upon what is right and proper and desire to drag out of the temple those who have taken asylum with God. It is not right that they should do this, since there is no crime with which they can charge us; it is utter madness to reprove in any way or not to stop inflicting suffering on those who seek refuge with God, whom we put forward as mediator and arbitrator in our dissensions.

to strive eagerly against him who smites you and to return to him the death he brings you, nor must you suffer the compatriot, who attacks with sword and kills, to come and go without receiving a blow, but deem every man an enemy who is evilly disposed to kill and let him fall. God's grace will surely be bestowed upon us if we keep out those blood-thirsty murderers from this holy temple and resist those who, with mouth agape, are eager to rush upon the holy vessels and furnishings and seize them as plunder. Were this not the case, and had they made the distinction between the sacred and the profane, they would long before have given up their desire to penetrate the outer and inner narthexes, since the victory was already theirs. They are so utterly shameless that not only do they imagine themselves as taking what is ours but these stupid men are also bent on appropriating the things of God. Nay, verily by Him who was nailed to the cross and by this my lance, they will most certainly fail in their attempts because God's things will be protected from defiled hands, nor shall we be abandoned.

Having spoken these words and other similar sentiments, he went down into the outer narthex where, as stated above, stands Michael, the Prince of the Heavenly and Sacred Hosts with sword drawn. The rest followed him as their commander, all bearing shields and looking like bronze statues. The kaisar then drew up his troops in battle array, fortified himself with the sign of the cross, and sallied forth before his men. The enemy forces in the open court of the Augousteon, thrown into confusion and pressed hard by the kaisar's first assault, poured out of the entrances; many of the imperial troops were wounded, and one was run through by the sword and killed.

Having spoken these words and other similar sentiments, he went down into the outer narthex where, as stated above, stands Michael, the Prince of the Heavenly and Sacred Hosts with sword drawn. The rest followed him as their commander, all bearing shields and looking like bronze statues. The kaisar then drew up his troops in battle array, fortified himself with the sign of the cross, and sallied forth before his men. The enemy forces in the open court of the Augousteon, thrown into confusion and pressed hard by the kaisar's first assault, poured out of the entrances; many of the imperial troops were wounded, and one was run through by the sword and killed.

After this, the kaisar returned to the place from which he had set out. Then the imperial troops no longer dared to enter the open court but preferred to fight by firing As the day was already in decline, the exhausted combatants stopped fighting. The patriarch dispatched to the empress his own servant, called a palatinos because his function was to present himself to the palace and convey recommendations to their Imperial Majesties and then to return thence with their answers. After he had threatened the empress with quick-sighted divine wrath that perceives in a flash unlawful acts wherever they may be perpetrated, and he had made known the kaisarissa's cries for a truce, there arrived as arbitrator of the dispute, the grand duke Andronikos Kontostephanos, together with the grand hetaireiarch John Doukas and many other distinguished nobles adorned with the highest dignities.

Yielding obedience to night's behest rather than trusting in conciliation, they brought an end to the fighting, and on the following day [3 May 1181] they plucked up their courage to renew hostilities. But the arbitrators came before the kaisarissa and her husband and gave her pledges of good faith confirmed by oaths, assuring her that nothing unpleasant would befall her. She would not be deprived of her dignities and priviieges by her brother the emperor, or her stepmother the empress, or the protosebastos Alexios, and full amnesty would be granted her supporters and allies. Thus battle was not joined a second time. Once the oaths were sworn and peace was concluded, the troops disbanded. With the coming of night, the kaisar and his wife left the temple and came to the Great Palace where the rulers resided.

Thus ended the affair concerning the kaisar and the causes for which this inglorious war began, bringing down upon us divine retribution for the sacrilege perpetrated in the holy temple. Nor do I absolve the supplicant kaisarissa from guilt, inclined as she was towards reckless acts and agitation against the government, and one could also accuse those who refused to yield even a little to her supplications, who preferred evil strife and, as a result, filled the house of prayer with bloody murder and were thus guilty of lawless conduct. The Roman general Titus, who besieged Jerusalem in ancient times, spared the Temple of Solomon and distinguished himself in his efforts to preserve it from destruction, exposing himself to the sorties of the Jewish legion within, with substantial losses to his own troops, rather than perform any act hateful to the gods against this sumptuous and wondrous work; this even though he was a man who did not know the God from whose temple he drew back, a temple that rendered false worship to gods who did not make the heavens. How much more then should God-fearing Christians pay honor to this most beautiful and holy temple which the hands of God648 have truly constructed and fashioned into an inimitable work of art from beginning to end, a veritable heavenly orb upon the earth.

The protosebastos was very angry with Patriarch Theodosios for ardently opposing his purposes and thwarting his designs. At first he suborned many bishops against him, corrupting them with gold and drinking parties. He proposed the patriarch's deposition in absentia for supposedly siding with the kaisarissa in her rebellion against the emperor and for allowing her to use the holy temple as a base of operations and with arms to stir up sedition and foolishly and thoughtlessly to incite a revolution. The protesebastos would have ousted him from the patriarchal throne with ignominy and by force had not the kaisarissa refused to give him the opportunity to remove the patriarch and replace him with another. She diligently guarded this most holy man lest, to deliver himself from troubles, he withdraw to the monastery he had built on the island of Terebinthos to live in quietude and she then be forcibly taken from the temple and subjected to great harm. The protosebastos now was able to gratify his anger by expelling the holy man from the sacred palace and confining him to the Pantepoptes monastery. He pondered diverse courses of action and wrestled with many ideas, meeting with the most wicked members of the senate and consulting those clerics who feared neither the vengeance of God nor the wrath of men as to how this holy man might plausibly and speciously be ousted. But he failed to achieve his aim, and no cause whatsoever could be found to justify the patriarch's deposition. Moreover, the empress and almost all, if not all, of the emperor's blood relations revered the man enormously. Then, against his will, the crooked serpent, unwinding his coils and swallowing down again the venom which he had prepared to vomit all over the saint, approved of the patriarch's return to his throne.

When the appointed day for his return had arrived, all the magistrates and clerics who loved virtue and honor, as well as the entire populace of the City, assembled at the holy monastery [Pantepoptes] and escorted him in a most splendid procession, showering the streets with perfume and filling the air with the scent of Indian sandlewood and aromatic fragrances. So huge was the number of people who joined in the procession that even though the patriarch set out at early dawn from the Pantepoptes monastery, he returned to the Great Church of the Holy Wisdom of God only late in the evening. So great was the shame that covered the faces of the bishops for condoning his trial that they avoided the public byways not only because of their sin against the patriarch and the universal derision heaped on them as a result but also because they were afraid that they might be killed. Thus were these events concluded.

When the appointed day for his return had arrived, all the magistrates and clerics who loved virtue and honor, as well as the entire populace of the City, assembled at the holy monastery [Pantepoptes] and escorted him in a most splendid procession, showering the streets with perfume and filling the air with the scent of Indian sandlewood and aromatic fragrances. So huge was the number of people who joined in the procession that even though the patriarch set out at early dawn from the Pantepoptes monastery, he returned to the Great Church of the Holy Wisdom of God only late in the evening. So great was the shame that covered the faces of the bishops for condoning his trial that they avoided the public byways not only because of their sin against the patriarch and the universal derision heaped on them as a result but also because they were afraid that they might be killed. Thus were these events concluded.

Andronikos, lifted up by his desire to rule, was set on the wing by the frequent letters flying at him from afar dispatched from the houses of the illustrious, as I have already stated. Finally his daughter Maria came to him as a runaway [May 1181], proving herself worthy of such a father, and he was provided by God with a teacher who instructed him fully as to what was transpiring in the palace. Spurred on like a racehorse by the words he heard from her, which were much to his liking, he crossed the borders of Paphlagonia, arrived at Herakleia in Pontos, and continued on his way, seducing and winning over all those he met on the way by his multifarious wiliness and insidious manner and dissembling ways; who, unless he had been made of insensate stone or his heart forged on an iron anvil, could have remained unmoved by the flood of tears shed by Andronikos as from a fountain of black water,657 and who could not but succumb to the deceitful, enticing, silver-tongued wheedling with which he professed his zeal on behalf of the right and expounded on the need to liberate the emperor [beginning of 1182?],

The protosebastos did not completely ignore these events, even though he was unmanly and not only spent the early morning in sound sleep but also wasted most of the day sleeping. So that the sunlight, so welcomed by other men, should not force open his eyes because of its brightness, he darkened his bedroom with opaque curtains and made the darkness his secret place659 whenever dealing with important matters. It would be closer to the truth to say that, delighting in dark deeds, he dispersed the nocturnal darkness with artificial light, and when the sun rose in the eastern horizon, nudging the wild beasts from their lair, he shut out the light with carpets and purple curtains. An effeminate dullard, he made the majority of the nobles dependent upon him in a novel fashion by washing clean the mouths of those whose teeth had rotted and smearing with pitch those men who [like corroded bronze statues] had been cast out long ago. By and large, he used the emperor's mother as an advance fortification or, to tell the truth, as an irresistible mollification (for she pulled in everyone as though on a line by the radiance of her appearance, her pearly countenance, her even disposition, candor, and charm of speech), winning over with bribes those who had suffered arbitrary treat- ment and lulling them to sleep with lavish gifts so as to gain their allegiance to himself as second in command to the empress. So no one who was enjoined to resist Andronikos, who was now in reach of the throne, went over to him, thus spurning the protosebastos, and none was taken in by Andronikos's masquerade as tyrant-hater.

The protosebastos did not completely ignore these events, even though he was unmanly and not only spent the early morning in sound sleep but also wasted most of the day sleeping. So that the sunlight, so welcomed by other men, should not force open his eyes because of its brightness, he darkened his bedroom with opaque curtains and made the darkness his secret place659 whenever dealing with important matters. It would be closer to the truth to say that, delighting in dark deeds, he dispersed the nocturnal darkness with artificial light, and when the sun rose in the eastern horizon, nudging the wild beasts from their lair, he shut out the light with carpets and purple curtains. An effeminate dullard, he made the majority of the nobles dependent upon him in a novel fashion by washing clean the mouths of those whose teeth had rotted and smearing with pitch those men who [like corroded bronze statues] had been cast out long ago. By and large, he used the emperor's mother as an advance fortification or, to tell the truth, as an irresistible mollification (for she pulled in everyone as though on a line by the radiance of her appearance, her pearly countenance, her even disposition, candor, and charm of speech), winning over with bribes those who had suffered arbitrary treat- ment and lulling them to sleep with lavish gifts so as to gain their allegiance to himself as second in command to the empress. So no one who was enjoined to resist Andronikos, who was now in reach of the throne, went over to him, thus spurning the protosebastos, and none was taken in by Andronikos's masquerade as tyrant-hater.

Nicaea, the preeminent and greatest city of Bithynia, refused altogether to submit to Andronikos, and John Doukas, who was charged with her watch and ward, remained unshaken by Andronikos's letters, even though his arguments were more devastating than the blows of siege engines and more powerful than any battering ram. Moreover, the grand domestic, John Komnenos, the governor of the province of Thrace, stopped his ears to Andronikos's enchantments and baited him as a tyrant. Pouring over his letters as though they were a smooth and shiny mirror, he clearly recognized Andronikos as a Proteus who took on many forms and now behaved in the manner of a tyrant.

When Andronikos approached Tarsia664 and the majority of the inhabitants round about the city of Nikomedia joined him, Andronikos Angelos, whose sons Isaakios and Alexios followed Andronikos on the throne, was sent against him with a considerable force. Hostilities were waged near the village of Charax, and Angelos was resoundingly defeated, although the forces he engaged were unequal and the opposing commander no match for him in battle; the clash was with a certain eunuch who had enlisted the services of farmers unfit for warfare and a contingent of Paphlagonian soldiers.

Immediately following the defeat, Angelos retreated ingloriously to the city and was required to hand over the monies designated for military expenditures. He worried lest he be apprehended on the grounds that he sympathized with Andronikos and had worsened the conditions he had been sent to improve, and persuaded by his sons, six in number and all young in heart and brave in deed, he undertook to fortify his own house, situated outside Kionion,666 by erecting ramparts; he also won over some of the populace to his side. But he realized that he did not have the strength to resist the superior imperial force and that he could not prevail over his adversaries and made arrangements to flee. Taking his six sons and his wife, he boarded a ship and went over to Andronikos. On seeing Angelos appoaching, Andronikos declared: "Behold, I will send my messenger before thy face, which shall prepare thy way before thee.

At his cousin's arrival, Andronikos took heart and saw that his aspirations were moving towards fulfillment. He discontinued his incursions into the byways; turning his back on the cities of Nicaea and Nikomedia and putting an end to his haphazard movements, he raced on to Constantinople as though he were making his way to the land of the Philistines." He camped on a site above Chalcedon called Pefkia [Little Pine Trees] and burned many watch fires all through that night, not for the needs of his own troops, but to give the appearance of a much larger army. This thrust the Byzantines into a state of suspense. In causing them to look out in the direction of the straits to see what was going on, Andronikos hoped to have them come down to the shore or ascend the hills so that even from afar he might signal them and win them over. So far then had advanced the cause of Andronikos, whose temples had grown hoary and forehead bald.

The protosebastos Alexios had no infantry with which to ward off the advancing enemy, for some had already decided in secret to pass over to Andronikos's side, even though they could not safely cross the straits to join him, while others thought that simply staying at home and taking no sides whatsoever was sufficient to prove their allegiance to the emperor.

Thus did craftiness of mind and the Roman emperors' frequent practice of ascending the throne through murder and bloodshed instruct the many to think and say.

Alexios attempted to repel the encroaching danger in a naval battle. Triremes covered the Propontis, some propelled by Roman oarsmen and manned with soldiers on deck ready to give battle, but the mightiest part and fiercest in battle were those of the diverse Latin nations residing in the City. On these the protosebastos poured rivers of money, since he relied more on them for assistance than on the Romans. He hastened to install as captains of the triremes those men who were most loyal to him and to entrust the fleet to his closest kinsmen, but when the grand duke Kontostephanos, who was in sole command of the fleet, proved adverse, Alexios was compelled to change his mind. Andronikos Kontostephanos took command of the entire fleet and blocked the passage across the straits from the eastern shore; with Kontostephanos were some of the protosebastos's kinsmen and domestics.

Shortly thereafter, the emperor dispatched a member of the clergy as his envoy to Andronikos. This was George Xiphilinos who, when he came into the presence of the tyrant, handed over the emperor's letters and elaborated on their contents. Included were promises of more bountiful gifts and greater dignities and the favor of God, the Prince of Peace, should he desist from his present plans, leading to civil wars, and return to his former way of life. It is said that Andronikos undermined the negotiations undertaken by the envoy Xiphilinos and refused to yield wholly or in part to the exhortations directed at him. He rejected the appeal and delivered a vaunted harangue to the envoys and angrily de- manded that if they wanted him to return whence he had come, let the protosebastos be cast out from the center of authority and account for his wrongdoings and let the emperor's mother confine herself to the monastic life, receiving the tonsure once and for all. As for the emperor, let him rule in accordance with his father's testament and not be choked, like an ear of corn by darnels, by those who share his reign.

Not many days afterwards, the grand duke Andronikos [Kontostephanos] defected to Andronikos, taking with him all the long ships manned by Romans. This act, more than any other, elated the rebel and utterly crushed the protosebastos; despairing of all hope, his spirit was broken. No longer did Andronikos's supporters meet in secret, but openly reviling the protosebastos and delighting at the turn-of events, they sailed over to Chalcedon. When they met Andronikos in troops, they marveled much at his noble stature, his comely form, and his venerable old age. Tasting of the honeycomb of his tongue and captivated by his grandiloquence, like water-grass drinking in the rain or the mountains of Sion soaking up the dew of Hermon, they returned rejoicing as though they had found the celebrated golden fleece, or the repast of ground meal cited in the myth, or the renowned table of the sun set before them and at which they were sated. There were those, however, who recognized at first sight the wolf in sheep's clothing and the serpent who attacks as soon as he is made warm and does evil to them who have taken him to their bosom.

After these events, Andronikos's sons, John and Manuel, and all the rest whom the protosebastos had incarcerated, were released, while his own favorites, supporters, and kinsmen were imprisoned. The protosebastos, who had been apprehended in the palace and placed in the custody of the Germans who carry on their shoulders the one-edged axes, remained in confinement. In the middle of the night he was furtively removed from the palace to the sacred palace built by Patriarch Michael, and his guard was increased for greater security.

0, how the course of events is reversed and sometimes is altered quicker than thought! He who yesterday initiated an undeclared war against the church, he who was insolent and self-willed and inordinately over-proud, dragging the refugees thence in defiance of propriety, he who had countless throngs buzzing around him, today is a captive without hearth or home, without follower, aide, savior, or redeemer. The protosebastos endured these things with great difficulty and was made to suffer even more: his guards would not allow him to sleep, and whenever he was about to doze off they fell upon him and compelled him to hold his eyes open as though they were horn or iron. The patriarch, who bore no malice but pitied the man's reversal of fortune, attended to his needs and relieved his distress by conversing with him. He urged the guards to treat him reasonably and not to make his lot worse than it already was.

Several days later, the protosebastos, sitting on a pony and preceded by a banner on a reed blowing in the wind, was led out of the temple in the early morning; abused in this fashion, he descended towards the sea. There he was thrown aboard a fishing boat and transported across the straits to Andronikos. Afterwards, his eyes were gouged out; all those in authority, who assembled publicly, sanctioned this act together with Andronikos.

Thus ended the joint reign of the protosebastos or, rather, his tyranny which was never firmly established. Had his hands been armed for battle and his fingers instructed for war, and had he not been a weakling warrioru4 and a stammerer spending half the day snoring, he could have barred Andronikos's way into the City and preserved himself from the evil of that time. He could have used the imperial treasury as he liked, and he could have employed the triremes, manned by Latin troops, to subdue his adversary Andronikos, as the Latins, wrought of bronze and delighting in blood, were superior to the Roman naval forces. But in their confrontation with destiny, the protosebastos, so it seems, lost his nerve, while Andronikos, exerting himself greatly, tripped him up at the heels as he came running against him and carried off the splendid victory.

While Andronikos was still biding his time across the straits, he dispatched all the triremes under the command of the grand duke, and with his elite troops that had been selected from among the soldiers who had enlisted in his cause as he made his way through the provinces, he mounted a war against the Latins in the City. The City's populace regained their courage and incited one another to fight side by side, and strife broke out on land and sea. Surrounded and hemmed in by both throngs, the Latins were unable to resist. They attempted to save themselves as best they could, leaving behind their homes filled with riches and treasures of all kinds such as are sought by men bent on plunder; nor did they dare to remain where they were or to attack the Romans or to submit to, and endure, their onslaught. Some took their chances by scattering throughout the City, others sought asylum in the homes of the nobility, while yet others boarded the long ships manned by their fellow countrymen and escaped being cut down by the sword. Those apprehended were condemned to death, and all lost their properties and possessions. The triremes, loaded with refugees, put out from the City's harbors in the direction of the Hellespont and spent the rest of that day anchored at the seagirt islands which are neither far from the queen of cities nor far out in the open sea: I speak of Prinkipos and Prote and all the islands around them rising up from the deep. The next day, after burning down and destroying several monasteries on these islands, they departed, plying all oars and with sails unfurled. Pursued by no one and putting in wherever they wished, they inflicted as much injury as possible on the Romans in these parts.

While Andronikos was still biding his time across the straits, he dispatched all the triremes under the command of the grand duke, and with his elite troops that had been selected from among the soldiers who had enlisted in his cause as he made his way through the provinces, he mounted a war against the Latins in the City. The City's populace regained their courage and incited one another to fight side by side, and strife broke out on land and sea. Surrounded and hemmed in by both throngs, the Latins were unable to resist. They attempted to save themselves as best they could, leaving behind their homes filled with riches and treasures of all kinds such as are sought by men bent on plunder; nor did they dare to remain where they were or to attack the Romans or to submit to, and endure, their onslaught. Some took their chances by scattering throughout the City, others sought asylum in the homes of the nobility, while yet others boarded the long ships manned by their fellow countrymen and escaped being cut down by the sword. Those apprehended were condemned to death, and all lost their properties and possessions. The triremes, loaded with refugees, put out from the City's harbors in the direction of the Hellespont and spent the rest of that day anchored at the seagirt islands which are neither far from the queen of cities nor far out in the open sea: I speak of Prinkipos and Prote and all the islands around them rising up from the deep. The next day, after burning down and destroying several monasteries on these islands, they departed, plying all oars and with sails unfurled. Pursued by no one and putting in wherever they wished, they inflicted as much injury as possible on the Romans in these parts.

During these days a comet appeared in the heavens, a portent of future calamities which clearly pointed to Andronikos. Now the fiery mass appeared to be stretched out, portraying a serpent's sinuous shape, and now it contracted into coils; at other times, opening up into a yawning chasm as though it were about to swallow from above everything below, thirsting after human blood, it struck terror into those who gazed at it. It continued on its course that day and through the next night, and then it vanished. And a hawk trained to hunt, with white plumage and feet shackled with thongs, that often molts in its nest and rejuvenates itself, swooped down from the east upon the Great Church of the Logos [Hagia Sophia]. It entered into the building of Thomaites, where it attracted many spectators who looked upon it as an omen. There were those who contrived means to capture him. The hawk rose up and flew down towards the Great Palace; coming to rest on top of the chamber where the newly crowned emperors were customarily acclaimed by the entire populace,688 it returned after a short time to the temple. Having thrice flown this same circuit, the bird was caught and taken to the emperor. The majority regarded this as a portent that Andronikos would be apprehended forth-with and subjected to violent punishment, for the omen of the bird's flight, they contended, clearly referred to Andronikos, since he had been frequently cast into prison, and the hair of his head was snow white. Others, more clever and discerning in their interpretation of the future, maintained that the threefold flight to the same destination augured that at the end of Andronikos's reign as emperor of the Romans he would once again be subjected to imprisonment and the stocks.

Everyone was ferried across to Andronikos, and the last to cross over was Patriarch Theodosios, together with the distinguished members of the clergy. When Andronikos heard that the great high priest was approaching his tent, he immediately went out to greet him, wearing a violet-colored garment of Iberian weave, open at the sides and reaching down to the knees and buttocks and covering the elbows; on his head he wore a grayish black headdress shaped like a pyramid. Throwing himself down in front of the horses hooves, he lay outstretched, mighty in his mightiness.689 Shortly afterwards, he rose up and licked the soles of the patriarch's feet, proclaiming him savior of the emperor, defender of virtue, champion of truth, and rival of John of the Golden Tongue [Chrysostom] and bestowed upon him every title of honor. The patriarch looked upon Andronikos for the first time and perceived his vicious glare as he scrutinized him, his insidious effrontery, his self-serving and affected manner, his stature reaching a height of slightly less than ten feet, his strutting, and his supercilious leer. He saw that Andronikos was a calculating man ever-wrapped in thought, who deplored those who so foolishly befriended him to their own utter ruin, and he declared, "Heretofore, I had only heard the report of you; now I have seen you and have come to know you very well." Quoting from the Psalm of David, he said, "As we have heard, so have we also seen," Thus artfully upbraiding Andronikos for this theatrical antics of throwing himself on the ground and fawning like a dog and associating what he saw with what he had heard from Emperor Manuel, who had so portrayed Andronikos in words that although he was unknown to the patriarch it was as though he were standing before his eyes. However, the equivocal meaning of the patriarch's words did not escape Andronikos of many wiles, who well understood the concealed meaning of the patriarch's words that pierced his soul like a sword bran- dished with both hands. Perceiving that the patriarch's thick brows knitted in anger revealed his innermost feelings, Andronikos remarked, "Behold the deep Armenian," for it was rumored that the patriarch's paternal family were Armenians.

Andronikos derided the patriarch yet another time. During a conversation with him, he appeared vexed and complained that he was the only remaining guardian of Emperor Alexios and that there was no one to share his toil and trouble, not even his holiness, even though the emperor [Manuel], Emperor Alexios's father, had entrusted his son to the patriarch's care and the administration of the state to him. The patriarch replied that he had long ago laid down his responsibility for the emperor and that from the time that Andronikos had entered the queen of cities and taken control of the government, he had been counted among the dead. At the patriarch's reply, Andronikos, turning red in the face, asked what he meant by laying down his charge and, pretending not to understand, asked him to explain his barbed statements. The patriarch, who did not want to enrage the beast and bring him roaring against him, or to make the camel vomit by forcing open its mouth, as is the custom, did not give the true meaning of his words but interpreted them differently, re- plying that he would no longer look after the emperor but would ignore his charge, for Andronikos alone was capable of caring for him.

Andronikos derided the patriarch yet another time. During a conversation with him, he appeared vexed and complained that he was the only remaining guardian of Emperor Alexios and that there was no one to share his toil and trouble, not even his holiness, even though the emperor [Manuel], Emperor Alexios's father, had entrusted his son to the patriarch's care and the administration of the state to him. The patriarch replied that he had long ago laid down his responsibility for the emperor and that from the time that Andronikos had entered the queen of cities and taken control of the government, he had been counted among the dead. At the patriarch's reply, Andronikos, turning red in the face, asked what he meant by laying down his charge and, pretending not to understand, asked him to explain his barbed statements. The patriarch, who did not want to enrage the beast and bring him roaring against him, or to make the camel vomit by forcing open its mouth, as is the custom, did not give the true meaning of his words but interpreted them differently, re- plying that he would no longer look after the emperor but would ignore his charge, for Andronikos alone was capable of caring for him.

Once the affairs of the palace were being managed by Andronikos's sons and supporters according to his will and pleasure, he finally departed from Damalis [April 1182]. As he was crossing over the the straits, he cheerfully recited under his breath the verse from David, "Return to thy rest, 0 my soul; for the Lord has dealt bountifully with thee. For he has delivered my soul from death, mine eyes from tears, and my feet from falling." When Alexios and his mother Xene left the palace and moved into the imperial buildings of Manganes in Philopation, Andronikos went there and made a profound obeisance to the emperor, embraced his feet, beating his breast as he was wont to do, and shed tears; paying his respects but perfunctorily to Xene, he left shortly afterwards. When he entered the pavilion which had been readied for him nearby, he was surrounded by the pitched tents of every noble and notable even as hens gather under their wings their chickens.

Once the affairs of the palace were being managed by Andronikos's sons and supporters according to his will and pleasure, he finally departed from Damalis [April 1182]. As he was crossing over the the straits, he cheerfully recited under his breath the verse from David, "Return to thy rest, 0 my soul; for the Lord has dealt bountifully with thee. For he has delivered my soul from death, mine eyes from tears, and my feet from falling." When Alexios and his mother Xene left the palace and moved into the imperial buildings of Manganes in Philopation, Andronikos went there and made a profound obeisance to the emperor, embraced his feet, beating his breast as he was wont to do, and shed tears; paying his respects but perfunctorily to Xene, he left shortly afterwards. When he entered the pavilion which had been readied for him nearby, he was surrounded by the pitched tents of every noble and notable even as hens gather under their wings their chickens.

At that time, a certain man, another Iros, a homeless and filthy wretch, was caught in the dead of night roaming around Andronikos's pavilion; his arms were bare to the shoulder and he was squint-eyed. At first, he was accused by Andronikos's attendants of resorting to sorcery, and then he was delivered over to the city populace; collecting dry wood and fagots in the theater, they burned him without benefit of a trial.

After spending many days with the emperor in Philopation, Andronikos decided to enter the megalopolis to see the tomb of his cousin, Emperor Manuel. He arrived at the Monastery of Pantokrator and inquired where the corpse was entombed;'" standing before the sepulcher, he wept bitterly and wailed piteously. Many of those who were standing nearby, not knowing what a dissembler Andronikos was, admired him greatly and remarked, "0, how wondrous! How he loved his kinsman, the emperor, even though he persecuted him relentlessly and showed him no mercy!" When several of his kinsmen tore him away from the tomb, saying that he had mourned enough, Andronikos gave no heed to their pleas and requested that he be allowed to abide a while longer by the grave as he had something to say alone to the deceased. He raised his hands as in supplication with his palms turned outwards and lifted up his eyes towards the marble sarcophagus, and moving his lips but making no sound that could be heard by his companions, he carried on a discussion in secret. To most, it appeared as though he were muttering some barbarian incantation. Others, especially those who wished to show off their wit, declared that Andronikos, to mock Emperor Manuel, clearly attacked his corpse by saying, "You have been my persecutor and the cause of my many wanderings, and you have made me the subject of nearly universal gossip as I miserably followed the course of the sun's chariot. And now this marble with its seven clusters of ivy holds you as a prison from which there is no escape while you sleep the sleep from which there is no waking until the last trumpet is sounded; I shall fall upon your family like a lion pouncing on a large prey, and I shall exact fitting revenge for the injuries I have sustained at your hands when I enter the splendid seven-hilled megalopolis."

Thereafter, he made his way to every illustrious and splendid dwelling, and stopping off as passers-by do, he conducted the affairs of state according to his will and pleasure, while encouraging Emperor Alexios to devote himself to the chase and indulge in vain pursuits. The guards he set over Alexios supervised his coming in and going out. with greater vigilance than the mythical many-eyed Argos and allowed no one to meet with him alone to discuss any matter whatsoever. Andronikos himself was wholly concerned, not with how to promote the welfare of the Romans, but how to remove from the palace the virtuous counselor and the devotee of the war god, mighty in combat, and anyone else who had distinguished himself by some exploit.

Thereafter, he made his way to every illustrious and splendid dwelling, and stopping off as passers-by do, he conducted the affairs of state according to his will and pleasure, while encouraging Emperor Alexios to devote himself to the chase and indulge in vain pursuits. The guards he set over Alexios supervised his coming in and going out. with greater vigilance than the mythical many-eyed Argos and allowed no one to meet with him alone to discuss any matter whatsoever. Andronikos himself was wholly concerned, not with how to promote the welfare of the Romans, but how to remove from the palace the virtuous counselor and the devotee of the war god, mighty in combat, and anyone else who had distinguished himself by some exploit.

He rewarded the Paphlagonians for their goodwill towards him and everyone else who joined him in his rebellion, honoring them with dignities and lavish gifts. Splendid dignities and magnificent offices were transferred to certain individuals according to whim, and he promoted his own sons. Stripping others of their offices, he awarded these as suited him to those who followed after him in the same way that those apostates of the living God in former times followed after Baal and preferred his glory to the praiseworthy honor formerly given to the righteous man as his portion.

Some of these men were expelled from house and native city and separated from their loved ones, while others were given over to prison and iron manacles, and still others had their eyes gouged out without any formal charge being brought against them. They were accused in secret because they were scions of nobility, and the fact that they were often victorious in warfare or distinguished by noble stature and excessive elegance, or by some other praiseworthy trait, nettled Andronikos and inspired in him no great expectations; instead, this only kindled the embers of old vexations, causing the ashes of forgotten wrath slowly to ignite.

The flux of those times was irresistible and the mutual distrust, even among the most genuine friends, an intolerable evil. Not only did brother ignore brother and father neglect son, if such was to Andronikos's liking, but they also cooperated with the informers in bringing about the utter ruin of their families. There were those who personally informed against their relatives for scoffing at Andronikos's actions or for being devoted to Emperor Alexios's hereditary rule, thus shaking themselves free from Andronikos's grip. In the very act of making accusations, many were themselves accused, and while exposing others as workers of evil against Andronikos, they themselves were denounced by the accused or by others who were present; both accusers and accused were led away to the same prison.

John Kantakouzenous attested that having struck with murderous fists a certain eunuch by the name of Tzitas, knocking out his teeth and bloodying his lips because he was discovered discussing the calamities that had befallen the commonwealth, he himself was seized on the spot, blinded, and cast into a dark dungeon for having sent a greeting through the jailer to the prisoner Constantine Angelos, his wife's brother.

For these reasons, therefore, the whole head was in pain, and these works were performed in the open as though they could never be verified, like the monstrosities subtly contrived by Empedoclean Strife. It was not only every man of high degree and distinction of the opposing faction who suffered most piteously; he was also most unfaithful to his own attendants. But yesterday he had fed them the finest wheat and set before them the fatted calf and mingled stronger drink of the finest bouquet, including them in the circle of his closest friends; today he treated them in the worst way possible. On one and the same day, one would often see the same man, like Xerxes' helmsman, both crowned and butchered, praised and cursed. Many who had sided with Andronikos, if they were at all perceptive, deemed praise from him to be a deliberate insult, the conferring of any human benefit the prelude to vomiting up one's possessions, and a show of regard, certain ruin.

When he had established his tyranny, it went unnoticed at first that he was a pernicious poisoner, but after an interval of some days, it was potions. The first to take this ruinous descent to Hades was the kaisarissa Maria, Emperor Manuel's daughter, who more than anyone longed to see his return to his country. By seductive promises he corrupted a certain eunuch by the name of Pterygeonites, Maria's father's attendant now in the woman's service, to pour the baneful drug into her cup; the poisonous potion was not the kind that brought on instantaneous death but lulled its victims little by little and drained their lives unhurriedly.

Not long afterwards, Maria's husband, the kaisar, followed the same fate as his wife. It was said that he too, did not die naturally but that man-slaying"' Andronikos was also the cause of his death, and it was conjectured that one wine cup had snuffed out the life of the two anointed ones."'

Andronikos wished to give his daughter Irene to Alexios in marriage. He had begotten Irene through his niece Theodora, the child of Emperor Manuel's brother; Theodora had given birth to her after having sexual intercourse with him. He drew up a laconic petition and, signing his name in ink at the bottom, submitted it to the holy synod for a hearing and deliberation. The petition dealt with the question of whether it was permissible to negotiate the marriage contract if only a slight impropriety were indicated, for the marriage would do much to unite the eastern and western parts of the empire, many captives would be rescued, and a host of other benefits would accrue to the public welfare. And this terse document, like some wide-mouthed soup ladle, or Poseidon's trident, or Discord's shapely apple, stirred up the synod and caused division among those senators who served as judges; it would be truer to say it armed them against one another and divided them into opposing factions. After they had been bribed with money and appeased by being promoted to higher dignities, the majority gave their approval. Would that they had not done so! They acted as though the marriage were not prohibited. The more insolent of the judges, accustomed to giving their votes in exchange for banquets as they went begging like vagabonds among the houses of the notables, and those members of the synod who were fond of gold and hucksters of divine things evaded the issue by contending that since the couple to be married were both born of illicit unions, the laws view such offspring to be unrelated and without any connection whatsoever, and they said that it was a sign of ignorance even to think of subjecting to inquiry a matter which is as clear as the day. The opposition would not even deign to give ear to such arguments. Using the laws as their weapons in close combat, they turned back the attacks and refused even more vigorously to condone so unlawful an act. Those who advocated this excellent judgment and supported the better cause were a few bishops and clergymen and several prudent members of the senate. The patri- arch's indignation rallied them and stirred them up, preventing them from siding with the impious and going astray. Neither did Andronikos's rant- ing perturb the patriarch, nor did the forcefulness of his words discomfit him, nor did threats confound him. He was as unshakeable as that jutting rock around which the high-rising wave is ever stayed and the brine roars and boils, dissolving the water into spray, making the sounding sea to howl loudly and afar as the rock remains firmly fixed on its foundations.

Realizing, therefore, that he could not prevail and that calamity was manifestly imminent and the worst evils were carrying the day, the patriarch rose up and departed from the sacred palace and came to the island of Terebinthos [September 1183], where he had prepared a place of refuge and a burial place for his body. Andronikos regarded Theodosios's unexpected and voluntary withdrawal as a great stroke of luck and completed the marriage contract, designating the archbishop of Bulgaria, who was present at that time in the City, to solemnize the marriage. He also deliberated on a candidate of his choosing to succeed to the patriarchal throne. He selected Basil Kamateros to become ecumenical patriarch [II, August 1183-February 1186]; it was stated that Basil enticed Andronikos to choose him by being the only hierarch who agreed in writing to do whatever was pleasing to Andronikos, even though these things be utterly unlawful, and also to abhor whatever was displeasing to Andronikos.

Not only were the affairs of the City in such turmoil, but the provinces suffered even worse, thanks to the evil spirit who overturned everything undertaken by the Romans to their disadvantage. The sultan of Ikonion, like Tantalos [Sisyphos?], forever in dread of the rock suspended above his head (I speak of Emperor Manuel), on learning of the latter's departure for the nether world took possession of Sozopolis by the law of warfare, and pillaging the surrounding towns, he brought them under his dominion. He afflicted the most splendid city of Attaleia with a long siege, sacked Kotyaeion [Kutahiya], and compelled many other cities to submit to him.

While residing in Philadelphia, John Komnenos, whose surname was Vatatzes, a man not lacking in military skill and one who had carried off many victories against the Turks, nobly set himself against Andronikos and took no heed of his orders. When the latter threatened him harshly, he rebuked him in turn even more sternly; distressed by the news that Andronikos was attempting to establish a tyranny, he roundly admonished and upbraided the tyrant as a demonic adversary intent on exterminating the imperial family.

As a result, the Asiatic cities were fraught with internal strife and wars. The actions now taken were more grievous than those undertaken by the neighboring enemies; in other words, whatever the hand of the foreigner did not pluck, the right hand of the inhabitant reaped, the kinsmen, ignoring the laws of kinship, went to war against one another as though they were barbarians.

Andronikos decided to arm Andronikos Lapardas, a man short in stature but enterprising in warfare, against Vatatzes and enlisted a sizeable force to serve under him. At this time, John Komnenos, who had taken ill and was encamped somewhere near the city of Philadelphia, marched his sons Manuel and Alexios against Lapardas. Vatatzes, who knew of the frequent turns taken by the conflict and that many on both sides were slain in these internecine struggles, was aggrieved and saddened by the malady that confined him to his bed at a time when he should have been defending the public good by displaying his military prowess. Then he would have received the customary acclamations from the eastern cities on the occasion of his victory and his deeds would have told the sort of leader with whom the old and decrepit Andronikos had matched himself. But eagerness resurrects even the dead, and there is nothing stronger than a sensitive heart '12' and thus he gave orders that he be lifted on a simple cot and carried to a hill whence the battle's progress would be visible. After he had instructed his sons as to how he wished them to array the troops, his forces won a notable victory, and Lapardas's men turned their backs and were pursued some distance and cut down.

A few days later Vatatzes died. After mourning bitterly, all of the Philadelphians decided to go over to Andronikos and eagerly winged their way to the imperial city. As they paid court to Andronikos, they croaked like cawing crows at the eagle Vatatzes and his eaglets and like drones buzzed around the streets and the palace, which is the practice of those who are mischievous and speak with forked tongues. The sons of the grand domestic, afraid lest they be apprehended and delivered over to Andronikos, departed and took refuge with the sultan of Ikonion, but what they were to suffer later makes it clear that no one is allowed to jump over the snares or to slip through the net cast by Divine Providence. Displeased after a lengthy sojourn with the sultan, who was unwilling to defend them against their enemies, they decided to set out for Sicily. With a fair wind, their ship sailed across to the Cretan sea, but a contrary wind blew up during their passage, and they were compelled to land on Crete where they were recognized by one of the sentries, an ax-bearer of Celtic origin. They were apprehended and reported to the exactor of tribute, who attempted to send them forth from the island safe and sound and furnished them with barley, wine, and with whatever other provisions were necessary for the voyage. But their presence had become known to everyone, and Andronikos was informed of the whereabouts of the wretched Komnenians, whereupon he who hated the light begrudged the men their eyesight and deprived them of the light.

Then Andronikos, who regarded the death of Vatatzes [Pentecost, 16 May 1182] as a divine visitation, added another deceit to the rest of his duplicities and advised Emperor Alexios that he should be crowned emperor. Shedding hot tears, he lifted him onto his shoulders'' and carried him up the pulpit of the Great Church in the presence of countless wit- nesses, both citizens and foreigners; carrying him back in the same manner, he appeared to be more affectionate than a father, one who accepted the charge to protect the youthful scion of the empire with his right hand and clearly fulfilled the saying of David, "For thou has lifted me up, and cast me down.

Zealously banishing everyone [from the court], Andronikos, now the lord of all, administered the affairs of the empire as he liked. His first objective was to remove the emperor's mother from the emperor. To accomplish this, he continually made accusations against her and threatened to leave because she was openly opposed to the common good of the state, saying that her every action was devious and that she actively conspired against the emperor. To incite the populace's outrage against her, he brought them together in the sacred palace on many occasions and, using the arts of the demagogue, persuaded them, to seize eagerly upon the resolution he had taken against the empress. He compelled the excellent Theodosios against his will to agree in writing to her removal from the seat of government and to her expulsion from the palace; shameless from among the base populace would have seized Theodosios by the beard in complete disregard of his famed piety if he had not acceded to Andronikos's demands and thus averted the danger of violence [August 1183].

From among the judges of the velum, Demetrios Tornikes, Leon Monasteriotes, and Constantine Patrenos, who had not as yet been added to the lists of those who belonged to Andronikos's circle not openly and servilely subscribed to his every whim and bent their knees in submission, very nearly lost their lives. When they were required to prosecute the empress for the charges brought against her, they responded that first they wanted to ascertain whether this tribunal and trial were taking place according to the will and pleasure of the emperor. Andronikos, as though pricked with an ox-goad by this query, declared, "These are the men who incited the protosebastos to perpetrate his foul deeds. Seize them." Forth- with, the bodyguards removed the two-edged swords from their shoulders as though to strike them down, and the populace, grabbing hold of their cloaks, insolently pulled them hither and thither so that they barely escaped with their lives.

Andronikos next attacked the grandees. The latter, who deemed such deeds intolerable and beheld the Cyclopean feast taking place before their very eyes, pledged to give no sleep to their eyes nor rest to their temples to insure that Andronikos would be dead and stained by his own blood before he should dye his garment with the purple he coveted. With fearful oaths they ratified their alliance against Andronikos, who, like some ferocious boar on a rampage of destruction, was bent on uprooting the imperial family. The conspirators were Andronikos, the son of Constantine Angelos, the grand duke Andronikos Kontostephanos, and their sixteen sons, all in their prime, with swords drawn for battle. They were joined by the logothete of the dromos, Basil Kamateros, and many other kinsmen and notables.