Verde Antique (Antico)

The most important columns in number and size are made of Verde Antique (Antico). This stone was selected not only for its color and pattern, by also for its compactness which makes it great as a structural stone and a perfect choice for columns. It comes from an important and famous quarry, operated during Roman and Byzantine times, at Chasambali, 12 km NE of Larissa city, close to the Omorphochorion village. You can see the Location on Google Maps. This quarry produced an ophiolite breccia, which was famous by ancient Romans and Byzantines, who called it “Green Thessalian”, “Lapis Atracius” or “Atracian Stone”, a name derived from the neighboring ancient city, Atrax. In modern times the term “Verde Antico” has used for this stone. One of the reasons for the great success of the quarry was the relative ease in transportation from the quarry across a dried-up lake bed and its closeness to the coast. You can still see the traces of the huge posts that were used to move the marble blocks along the ancient road. During the reign of Justinian I ships were built to transport large cargoes to support his wars. There were probably ships that had been built to carry heavy cargo like columns and other marble church furnishings. A 6th century shipwreck, called the Marzameni Church wreck, carrying 350 tons of marble, has been discovered that was carrying the complete fittings of a church from Constantinople to Italy or Dalmatia. It had sailed from the island of Proconnesian and was wrecked off the coast of Sicily.

All the pieces belonging to the ambo of the church were made of Verde Antique, while the 28 bases, 28 Corinthian capitals, and many fragments of columns shafts (with the exception of one) and decorated slabs are of white Proconnesian marble.

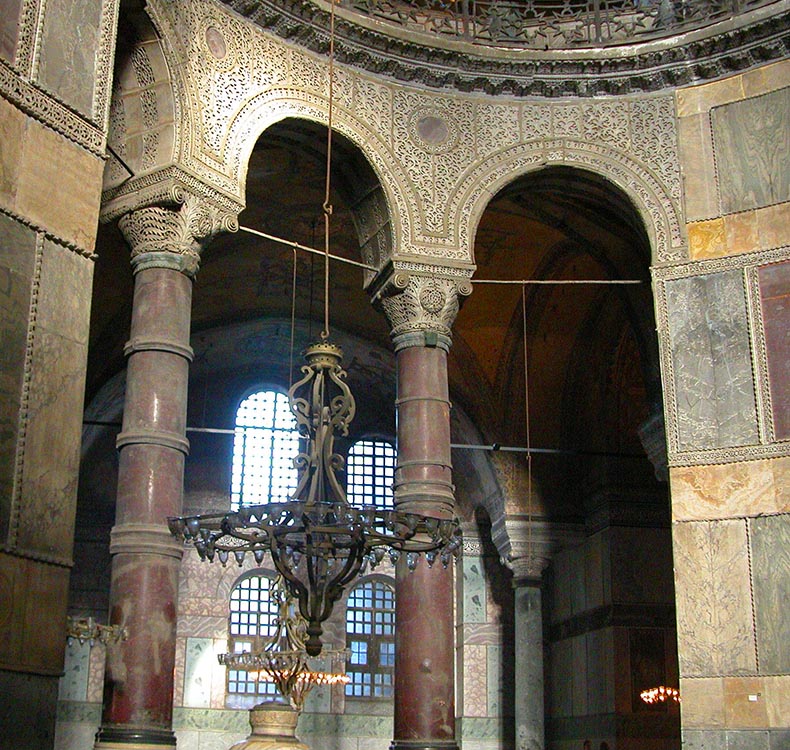

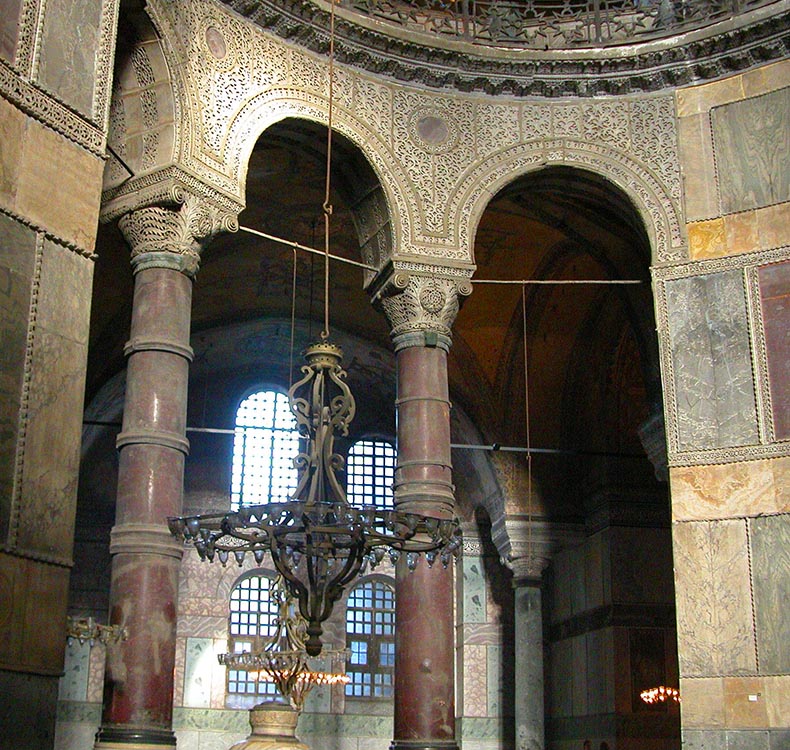

The giant Verde Antique columns on the ground floor of the nave are 34 ft tall including capitals and bases. These monoliths vary in diameter up to six inches. The shafts themselves are 28 ft tall. The Verde Antique columns in the galleries come in two sizes, 16 and 15 ft tall.

Columns and other marble blocks of Verde Antique were extracted from the quarry in slabs and massive, monolithic blocks. They were cut from the rock mass by digging out a channel, 30 to 40 cm wide, around the perimeter of blocks. Next, to separate the block from the mass of rock the quarrymen chiseled out small cylindrical cavities, 10 to 15 cm long, and then pounded wooden wedges into these holes. Water was then poured in which expanded the holes which fractured and split off the block.

You can still see the chisel and pick axe marks in the quarry where the monolithic columns were extracted. There is one vertical cavity, 9m tall, that exactly matches a column in Hagia Sophia. They came from huge horseshoe shaped quarries that had rock faces that were 35 meters tall. The are huge piles of spolia that came from the extraction and shaping of slabs and columns here to make them ready for shipment. A large Byzantine-area cross can still be seen carved on the wall of this quarry, reminding us of the dangers faced by the quarrymen. The quarrymen in these mines would have included both free workingmen and slaves. In Roman times quarries were usually worked by slaves, who were forced to produce perfect columns regardless of the costs physically or the number of hours spent on each one. By the time of Justinian there were fewer and fewer slaves to do the work. Part of the reason was Christianity brought a new morality to businesses like these. Working slaves to death was immoral. Free quarrymen would not be forced to perfection in rounding and polishing of columns. The relaxing of standards can be seen columns made for Hagia Sophia. So, the production of marble from the quarry was highly technical and required great skill and training, It was more expensive to produce when the wages of free men had to be paid. Even the work of carving out the channels around the blocks of stone, which one would expect could have been done by anyone, required an almost instinctive knowledge of the stone you were quarrying that could only come from years of hands on experience with it. Verde Antique is very hard, full of fractures in the structure of the stone that can easily crack and split.

Below is an image showing how slabs are split off the quarry walls.

All of the Verde Antique ophiolitic breccia marble used in Hagia Sophia came from came from the quarries on Chasambali hill. You can also find the same stone used in St. Demetrius and Acheiropoietos Basilica in Thessaloniki. In Constantinople it was used in the churches of Saint Sergius and Bacchus, the Church of the Holy Apostles and St. John of Studion. It was also used for Imperial tombs, you can see one that was reused for the Augusta Eirene, wife of John II Comnenus in the other narthex of Hagia Sophia. The combination of the green color of Verde Antique columns combined with white Proconnesian capitals is really beautiful.

The quarries in Chasmbaki were abandoned in the 7th century. Work stopped at most ancient Byzantine quarries at the same time. Economic decline ended huge building projects like Hagia Sophia. Wars and plagues had reduced the available workforce to work the mines and made transportation impossible. In later times Byzantine architects recycled columns, church furnishings and revetment in Verde Antique into new building projects.

In 1860 the ancient quarry was rediscovered by an Englishman and it was reopened. Work in the quarry stopped in 1980. You can see Verde Antique used in British churches like Winchester Cathedral. You can see the traces of this work in the quarries which damaged much of the traces of the work of the ancient quarrymen. You can still see huge blocks of stone lying around the quarry. You can see one below.

The columns of Hagia Sophia in Verde Antique were unloaded, brought up from the harbor to the building site and finished there. Final polishing of them was done after they had been erected in the church. The nature of the breccia stone - which is made up of hard and soft masses makes it difficult to create a soft and even surface. All the columns feel a bit lumpy to the touch. They also feel a bit greasy because they contain so much serpentine. It is possible that the columns have never been re-polished since they were installed. Around the bases of the columns you can see how the rubbing of them for hundreds of years has left its own sheen left by human hands. The Verde Antique elements in Hagia Sophia have suffered from a chemical transformation to their surfaces to talc, which makes them loose their color and look gray. The surfaces could be restored. Over the centuries parts of the columns were seen to be fracturing off. Metal clamps were applied to secure them.

Below is an example of a modern slab of Verde Antique from another nearby quarry that is currently working. You can see how bright the green is and the pretty white fractures and veins in the stone are easy to see. You can also see these masses of elements what are in the breccia I mentioned earlier. This slab has a modern machine-made polish.

I think the ambo/solea columns from the sanctuary of Hagia Sophia are to be found in Topkapi Palace. Those columns were probably made of Verde Antique. below you can see a picture of two of them. They are the right size and have attached tall bases where the parapet slabs would have been set.

Red Porphyry

These columns are from the north eastern exhedra of the nave of Hagia Sophia. There are eight of them. Porfido rosso antico were quarried by slaves at Gebel Dokhan (the ancient Mons Porphyrites) in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. The quarries stopped production in the fifth century and these columns were reused or came from existing stock. They vary in size from 24 to 25 feet tall, and the bases are of different heights to fit the column. The columns are set into soft lead blanks at their bases. This prevents earthquake damage. I have read that the columns are not all monoliths, but have been assembled in pieces and that some of the collars mark these joints. One is fractured. The stone is extremely hard and difficult to fashion into columns. It is also brittle, splits and flakes. You can see how bronze (or lead) collars have been added to stop them from cracking under the immense weight they carry. These collars were added very early in the history of the church. We don't know how they came to Constantinople or where they brought from. They could have come from Rome at the time of Constantine or have been brought from some capital during the Tetrarchy, like Nicomedia, the modern Izmit, not very far from Constantinople. Paul the Silentiary says that the columns were brought from Thebes in Egypt. It is possible there were still some porphyry columns "in stock" there that didn't need to be quarried. This would explain their different sizes. There was a contemporary story told that the columns were sent from Rome by a widow named Marcia, and they formerly stood in Aurelian's Temple of the Sun.

Manuel I Comnenus placed his enormous 4-slab, 15 ft wide, marble inscription recording the edicts of the church council of 1166 on four slender columns of Red Porphyry - around 6 ft tall - in Hagia Sophia. They were placed in the north aisle - the left-hand side as you enter the church. There is actually a spot next to the northwest pier with floor patches where the columns would have been set. The space is exactly the right size. In 1566 these columns might have been sent to the construction site of the Süleymani̇ye Mosque.

There were probably other small to medium-sized porphyry columns in the church that have not been recorded in historical accounts.

There is a really pretty altar in Red Porphyry on exhibit in the outer narthex of Hagia Sophia. Its true beauty is in the stone, not in the rather crude carving. It's a pagan altar that was used to burn incense, probably from the late 3rd or early 4th century. The laurel leaves are similar to of the decoration on the porphyry bands on Constantine's Column. Here's a picture of the altar taken by Ken Grubb:

Pilgrims who visited Hagia Sophia were very impressed by these porphyry columns, which they believed had the relics of saints in them. Is it possible that relics were attached to them? Perhaps they were attached to the collars.

Robert of Clari wrote about the columns and their healing power:

"The Cathedral of Saint Sophia was altogether round. And there were on the inside of the minster, all round about, arches which were borne up by great pillars – very rich pillars, for there was not a pillar that was not either of jasper, or of porphyry, or of other rich and precious stones, nor was there one of these pillars that had not some virtue of healing. For one there was that healed a man of the disease of the reins (kidneys)when he rubbed himself against it, and one that healed folk of the disease of the side; and some that healed them of other diseases."

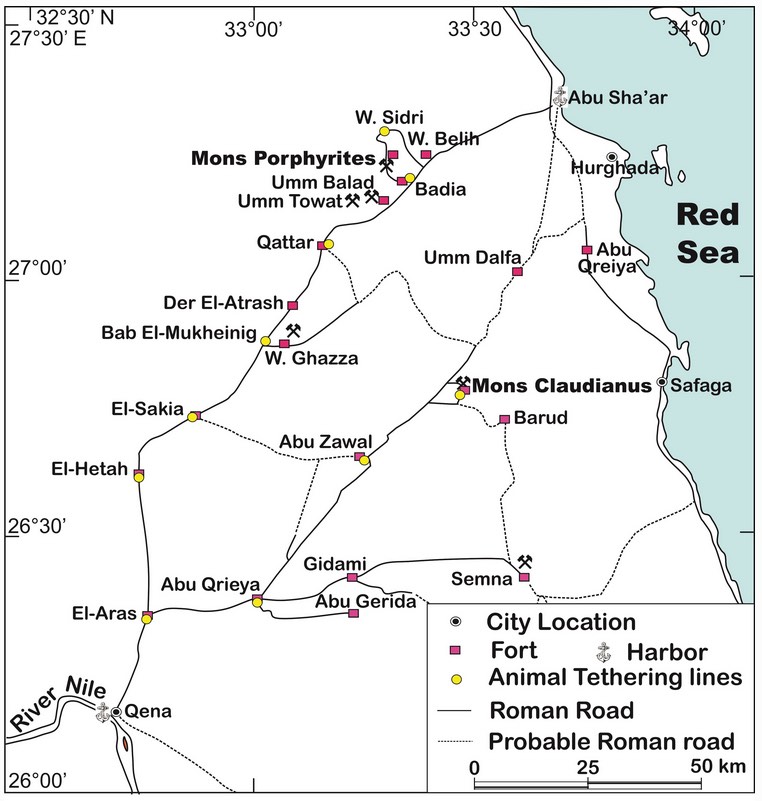

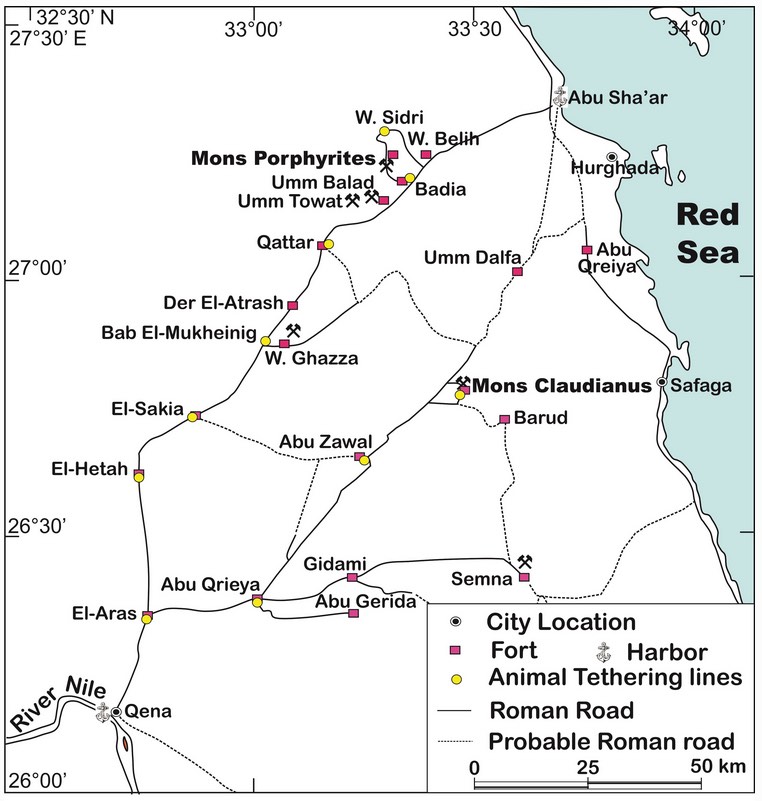

Above is a map of the quarries. In the eastern desert of Egypt are located about 45 km west of Hurghada the Mons Porphyrites quarries where our columns originated. The Roman legionnaire Gaius Comenius Leugas discovered the red porphyritic rock in 18 AD in the stony, rugged and towering mountains of Wadi Abu Ma'amel, an extremely dry desert. I have no idea how or why he found it. The quarries where worked by slaves in horrible conditions. Thousands of them must have died making columns like this. There was no water o food, everything had to be brought in. The hard stone dulled the metal tools used to work it and they had to be constantly resharpened. It must have been seasonal work - I cannot imagine the work continuing in the summer when the temperature is as high as 40 C. Below is an image of the site:

Above is a map of the quarries. In the eastern desert of Egypt are located about 45 km west of Hurghada the Mons Porphyrites quarries where our columns originated. The Roman legionnaire Gaius Comenius Leugas discovered the red porphyritic rock in 18 AD in the stony, rugged and towering mountains of Wadi Abu Ma'amel, an extremely dry desert. I have no idea how or why he found it. The quarries where worked by slaves in horrible conditions. Thousands of them must have died making columns like this. There was no water o food, everything had to be brought in. The hard stone dulled the metal tools used to work it and they had to be constantly resharpened. It must have been seasonal work - I cannot imagine the work continuing in the summer when the temperature is as high as 40 C. Below is an image of the site:

Due to the dry desert conditions the remains of the quarry and the attached settlement for the workers has been preserved and tells is a lot about the people and the working conditions. Seeds, charcoal, bones of mammals, birds and fish, shells of mussels and snails, ceramic household objects, pottery oil lamps, broken glass, stone objects such as millstones, coins, remains of metal objects, items in carved ivory, remains of wooden objects, lots of textiles and fabric remnants, sandals and baskets along with the remains of leather have been found there. In addition, numerous written accounts have been discovered there. The quarries were no longer worked after the 5th century. It was not until 1822 that the British adventurer James Burton accidentally discovered the quarries in the this remote region of Egypt.

This red porphyry has a Dacitic to Andesitic composition and comes from volcanic melts from the Ediacarium, which covered a very large area in the mountains of the Eastern Desert.

The porphyry of this region not only comes in red, but there are also black, gray, green and pink varieties, which also differ in the size of the feldspar crystals. Red porphyry is composed of the white feldspars, black amphibole crystals and the ore minerals in the red matrix. The wonderful red color is caused is a high content of hematite.

In Roman times the managers of the Imperial quarry built a 118 mile long road, called "Via Porphyrites" for the transport as well as the supply of quarry operations The road was run between the quarry and Quena located on the Nile, over which the transport of up to 45 ton heavy stone blocks were made. Parts of the up to 30 feet wide road can still be seen. We are told big wagons were pulled by donkeys; oxen could not be used in the heat.

Porphyry columns, sculpture and panels cannot be carved - especially the red imperial porphyry - which is very hard must be ground and polished; the green areas are softer. It does not weather or age, chipped splinters and broken pieces show virtually no signs of weathering even after more than 1,500 years.

The mining of columns and blocks was done in a similar way to that mentioned earlier regarding Verde Antique, but here would have been smaller channeling around the blocks and more use of wedges and splitting of the stone. The yield of the quarry was small, only 25% of what was quarried could be used. The finishing and shaping resulted in only 10% was shipped out. Working the stone in the quarry reduced the weight and made transportation to the Nile easier. We know that final finishing of porphyry was done in Rome. We are also told that Constantine imported blocks of porphyry from Rome to his new capital. It does not seem likely that the finishing work on the drums was done in Constantinople other than polishing. In order to save on the limited supplies they had to work with, the workers in the decoration of Hagia Sophia had to piece together pieces of porphyry to compose revetment panels, demonstrating amazing technical skill and precision with porphyry.

That Red Porphyry column in Constantinople was erected by Constantine the Great in his circular forum in 328, where it still stands (minus the forum, which has vanished). It was not a monolith, it was around 131 feet tall with its capital and base, the gilded statue on the top added another 20 ft to it. It was made of seven colossal 10 ft tall blocks - 63 tons each - of Red Porphyry fitted together with bands of laurel leaves. They had trouble with the column from the start. In 416 a large part of the bottom drum split off and was smashed on the floor of the forum. The gash was never filled in and the entire column was encased in a bronze lattice to keep it together. One theory about its origin is that the column parts were intended for a monument to the emperor Diocletian that was never completed. It still survives, battered and humiliated in old-Istanbul. It's interesting that Constantine's column was higher than Trajan's great column in Rome.

Here are the remains of columns in the quarry. One of them, a 60 feet long column (at the base 9 feet in diameter) was intended for the Pantheon in Rome, with a weight of 200 tons.

There were a number of huge porphyry columns in Constantinople, including the great Pillar of Constantine in the center of his circular forum. You can read more about it here. It was 165 feet tall and was originally crowned with a huge gilded statue of Constantine the Great. The statue fell down in the 12th century and was replaced by a huge gilded cross. There were also big columns of porphyry in the Philadelphion with sculptures of the Tetrarchs on them. Pieces of them have been mounted on the facade of St. Marks in Venice. Many porphyry columns were used in the Great Palace and in Blachernae Palace. Some of these were taken to Venice after 1204 and were placed on either side of the main doors to the church. They were damaged in transit. We know porphyry was used in the Blachernae palace because numerous fragments of columns and revetment panels have been found there.

There were a number of huge porphyry columns in Constantinople, including the great Pillar of Constantine in the center of his circular forum. You can read more about it here. It was 165 feet tall and was originally crowned with a huge gilded statue of Constantine the Great. The statue fell down in the 12th century and was replaced by a huge gilded cross. There were also big columns of porphyry in the Philadelphion with sculptures of the Tetrarchs on them. Pieces of them have been mounted on the facade of St. Marks in Venice. Many porphyry columns were used in the Great Palace and in Blachernae Palace. Some of these were taken to Venice after 1204 and were placed on either side of the main doors to the church. They were damaged in transit. We know porphyry was used in the Blachernae palace because numerous fragments of columns and revetment panels have been found there.

The emperor Theophilus found four large porphyry columns for an addition to the Great Palace he built, a hall with three apses called the Triconchos. The columns were set on either side of the arches of the apses.

There are 3 pair of porphyry columns in different sizes that were taken from other sites, including the ruins of the Church of the Holy Apostles and the mausoleum of Constantine; and used in the Süleymani̇ye mosque in the 1550's. Two huge ones - 19 feet tall, 6 feet shorter than those in Hagia Sophia - are on either side of the main entrance. They are not in great shape and look like they could split, shatter and collapse in the next quake. They have special collars to reinforce them, but they were obviously put on centuries ago and have done nothing to prevent the huge fissures and flaking that has occurred. Great chunks have fallen out of at least one the columns.

There are four Imperial sarcophagi in Red Porphyry in front of the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul. These all came from the mausoleum at the Church of the Holy Apostles. On the left you can see one of them.

There were nine porphyry sarcophagi, in which rested the first eight Emperors of Constantinople, and the wife of the Emperor Arcadius, Eudoxia. They were 1) Constantine the Great (324-337); 2) Constantius (337-361); 3) Julian the Apostate (361-363), 4) Jovian (363-364); 5) Valens (364-378); 6) Theodosius I the Elder or the Great (379-395); 7) Arcadius (395-408); 8) Theodosius II the Younger(408-450); 9) Marcian(450-457), the last emperor who was honored with a porphyry sarcophagus.

Five of these were found on the grounds of the Church of St. Eirene and the others were found in the 20th century on the grounds of the Old Seraglio and local mosques the other 4 were discovered.

There was a special room in the Imperial place that was decorated with porphyry. Anna Comnena describes it in her Alexiad. Imperial births took place here, which would give you the attribute "Born in the Purple" :

"This purple room was a certain building in the palace shaped as a complete square from its base to the spring of the roof, which ended in a pyramid; it looked out upon the sea and the harbor where the stone oxen and lions stand. The floor of this room was paved with marbles and the walls were paneled with it but not with ordinary sorts nor even with the more expensive sorts which are fairly easy to procure, but with the marble which the earlier Emperors had carried away from Rome. And this marble is, roughly speaking, purple all over except for spots like white sand sprinkled over it. It is from this marble, I imagine, that our ancestors called the room "purple."

Proconnesian

Hagia Sophia has many round and square columns in Proconnesian marble. The island quarries are only 70 nautical miles from Constantinople and produced huge quantities of marble for the city as well as the church. Without the availability of so many marble sources close by the emperors from Constantine to Justinian could not have created the magnificent city on the Bosphorus. Marmo di Proconneso is a coarse-grained calcite marble with grey graphite-bearing banding. It also sometimes called marmo cipolla, although it is very similar to Hymettian marble (variously called marmo cipolla, Imettio or marmo greco fetido), from famous Mount Hymettos in Attica, Greece. The floors of Hagia Sophia were paved with blue-banded Proconnesian marble that was laid to resemble waves. Below is an example:

The Proconessian columns in Hagia Sophia seem to have stood up very well to the force of the pressure of the great arches and vaults of the building. However, they are extremely dirty and need to be cleaned. Below is an image showing how some column bases have two types of collars. The large dark collar is lead and the rusty looking ones are iron.

The island of Proconnesus, today known as Marmara island, is situated in the eastern part of the Propontis Sea or Sea of Marmara. The island’s prosperity was mainly due to the marble quarries and the export marble trade which was possible thanks to its harbor. The principal Proconnesian products that were exported abroad were marble columns, bases, basket-capitals, ambos, rectangular chancel reliefs and blocks for pavement and revetment for Early Christian churches. Proconnesian quarries also produced a large number of sarcophagi and rarely statues. Those products were exported by ships mainly to Constantinople, to Europe, North Africa, Crimea and the Middle East. The famous shipwreck off the east coast of Sicily near Marzamemi, was a Byzantine ship dating from the early 6th century that departed Proconnesus, passed from a harbor of the Aegean Sea and headed to Italy or North Africa. Then it lost its way in a storm and hit the reef at Marzamemi. This ship carried a 350 ton load of prefabricated building materials, such as marble slabs, columns, 28 columns, with bases and capitals in Proconnesian marble which were intended for the interior decoration of a Christian basilica. One can only imagine the vast amounts of marble needed for the Hippodrome, the vast forums and street colonnades of the city of Constantinople from the quarries of the island.

The largest recorded Proconnesian marble columns were 8 monoliths 52 feet tall that were quarried for the Basilica of Maxentius in the Roman Forum at the beginning of the 4th century. The nearby fluted Proconessian honorific column of Phocas in the Roman Forum is 45 ft tall and not a monolith, being built from drums of marble.

It is estimated that it took a year to quarry, ship and install the columns in the Basilica. These columns weighed 100 tons each. Since the largest transport ship of the time could carry 250 tons, 4 cargo vessels would have been required. The Romans had long used Proconessian marble, the arch of Trajan in Ancona was entirely built from blocks of it. Considering the availability of local Italian marbles this means Proconessian was specifically chosen for it.

Below are two pictures one of the Proconnesian quarries today. The first one is a view of an ancient quarry with many rejected pieces strewn about. The second one is a collection of unfinished pieces from Byzantine times that have been found around the island.

The quarrymen on Proconnesus used the same technique to cut and extract blocks as mentioned earlier in describing who Verde Antique was mined. The stones they extracted were fashioned into blocks, columns and roughed-out capitals. They also fabricated architectural elements - like lintels and window frames. Items like capitals were not shipped fully carved because the details of sculpture would most certainly be damaged enroute. If their were no local carvers in the destination city, teams of carvers were dispatched to do the finish work onsite. Styles of capitals changed over time and savvy church builders wanted the latest designs from Constantinople to decorate their churches and palaces.

Marble was taken to the harbor hauled by by oxen and loaded on ships. If they were bound for Constantinople the voyage would be short. The sea transport was done by big cargo boats upon which were loaded the smaller marble blocks, whilst the bigger ones – in order to be lighter – were hung in the water with wooden beams, which were supported by two other cargo boats. The builders of Hagia Sophia were able to place special orders and get the marble really fast from here. The quarries where controlled by the government and responded quickly.

Until the mid-sixth century, during the reign of Justinian I when Hagia Sophia was built by him, church construction and export marble trade on the island remained at a high level. Justinian actually built a palace for himself here and was followed by Byzantine aristocrats who wanted to be near the emperor. The presence of the Imperial court, its servants and retainers, brought great prosperity to the island for a short period of time. However, in the early seventh century the quarries of Proconnesus were abandoned. The reason of the abandonment was the fact that building in the public sector of Constantinople had ended and would not return for centuries. Plagues, wars and economic disruption meant there was no money for new buildings and the plagues wiped out half the population leaving few survivors to work the mines. So the need for marble had vanished and orders were reduced to nothing almost overnight.

It's interesting that the last 17 monolithic Proconnesian columns from the sphendone of the Hippodrome were removed and reused in the building of the Süleymani̇ye mosque in the 1550's, where they can still be seen. FYI - the columns of Hagia Eirene and the Theotokos Peribleptos (154 cartloads of stone and marble) went at the same time.

In the Middle Ages Constantinople was able to supply its need for marble from the vast reserve in reused stock.

Troad Granite

The ancient sources tell us that Hagia Sophia had columns of Troad Granite. I have searched and searched for any in Hagia Sophia without success. There are sets of columns that have been removed from Hagia Sophia. First, there were 24 columns in the atrium, the atrium has vanished along with the columns. These were outdoors and Troad granite would have been the right choice for those conditions. We know that Troad granite was used in other outdoor colonnades. The Emperor Anastasius used dozens of Troad granite columns with Proconnesian marble capitals and bases in the circular forum he built around 500 in his hometown of Durres. Somewhere I have an old photograph of a surviving column that was built into the remains of the atrium wall. The last two columns of the atrium was removed in 1873. At the time it was reported that it was part of a supposed passage between Hagia Irene and Hagia Sophia, but no such passage existed. Now we know for sure it was the last surviving part of the colonnade of the atrium. I am still looking for the picture.

In 1740 a great 8 column fountain was built by Sultan Mahmut I next to Hagia Sophia. At least two of the columns are made of granite. Can one assume these came from the nearby atrium?

Second, there were columns in the ambo, altar canopy and sanctuary colonnade, which is called a templon. Troad granite columns are very plain, so I m certain they would have been used there. There are two columns on the southeast entrance to the church but I have not been able to find out what stone they are. This was the spot where the emperors of Byzantium normally entered the church at the so called "Holy Well of the Samaritan Woman", which was transferred here by Justinian in the sixth century. Justinian brought both the head of the well and the stone which Christ has sat upon when he spoke with her. The well has been described as a hollowed out piece of marble like a pot, however there was also a real well there which still exists. These relics were the source of many cures, especially for people suffering from fevers and chills. There were a series of chapels running along the eastern end of the church which included the Holy Well. The entrance to the Chapel of the Holy Well inside Hagia Sophia is still there at the eastern end of the south aisle. The Chapel -"passage" to be exact - of St. Nicholas was also there. Russian travelers described the Chapel of the Holy Well as being between the Chapel of St. Nicholas and the "very beautiful columns, like jasper", meaning the porphyry ones. I used to have a picture of the chapel in a book, "The Brazen House" by Cyril Mango which I have misplaced and sorely miss!

I believe the eastern chapels were messed around with when Andronikos II Palaeologus built these massive buttresses against the apse in 1317. Andronikos used the remains of the great ruined churches of the 40 Holy Martyrs and St. Mocius the Martyr to build these. Despite their ugliness, they were expensive to build, Andronikos used money from the estate of his second wife, Irene of Montferrat to pay for them. His son John V also used the stone of St. Mocius to rebuild the Golden Gate.

This eastern entrance to the church also takes you to the Chapel of St. Nicholas.

Now to return to the discussion of atrium columns - it's an interesting mystery about where the atrium columns went. In the 18th century the Ottomans built many new mosques and we know they brought columns from the Troad quarries. There are many unfinished columns just lying there, perhaps they brought those and finished them, rather than quarrying new ones.

Here is an image of the back entrance to Hagia Sophia. There are six columns here of all types and with different capitals that don't match. They are different types of marble.

It's interesting, above this entrance you can see the eastern wall of the South Gallery. You can see the famous door that once led to a spiral staircase and passage that ran from from Hagia Sophia to the Great Palace via the famous Chalke Gate. The emperors used this spiral staircase to move up and down between the nave and the South Gallery where the 2nd floor Imperial Chapel was along with the Deesis mosaic. This door now opens out into open air and is next to the mosaic of John II Comnenus and the Augusta Eirene.

There are eight Troad granite columns used in the nearby "German Fountain" which was given by Wilhelm II, the German Kaisar to Abdulhamit II in the summer of 1898. Perhaps these columns came from the atrium.

There are many Turkish fountains and gates around Hagia Sophia that have columns. Most of the columns in Topkapi Palace came from Byzantine buildings. I have always suspected that missing columns from Hagia Sophia - including the ambon - are there. I have posted a picture of them above.

Troad granite columns were produced under state control and were owned by the emperor. Concessions were granted to private businesses to exploit the quarries. It was generally used in small and medium sized columns as an alternative, much cheaper alternative to Egyptian granite. It is another stone that is found very close to Constantinople, being on the Sea of Marmara. Shipping would have been through the port of Alexandria "Troas".

Troad granite, therefore, can be considered as a replacement stone used mainly in the provinces in imitation of the growing tendency to use grey granites in the imperial architecture of Rome. While granito del Foro would have been almost exclusively used in grand imperial architecture, private, civic and provincial projects would have had access to Troad granite, which was very similar, but much cheaper. There were many quarries in the large district of Troad; a certain number of columns have been connected for each of them, which allows us to draw some conclusions. For example, in the Koçali quarry at least twenty 40-foot-high column shafts are preserved similar therefore to an example still preserved in the ruins of the port warehouses of Alexandria Troas where columns were stored before shipping.

Granito violetto, marmor Troadense, comes from Çigri Dâg, Canakkale and the Sea of Marmar. It is a medium-grained quartz monzonite with large violet-grey megacrysts of potash feldspar in a groundmass of quartz, plagioclase, biotite and hornblende. It is believed to be a dark variety of granito violetto, also known as granito Troadense or marmo Troadense. Although this description sounds very colorful the stone is not very interesting and is a rather plain granite. It was exported to Rome between the second and sixth centuries and was said to have been widely used in Constantinople. I think some of the great commercial colonnades around the Forum of Constantine may have had columns of Troad granite. I also think there are some built into the walls of the Blachernae.

Below are two images of the Troad quarries today showing these unfinished column shafts still in place:

An example of a "wind-blown" acanthus capital on a column of verde antico.

An example of a "wind-blown" acanthus capital on a column of verde antico. Here is capital carved in proconnessian white marble with eagles.

Here is capital carved in proconnessian white marble with eagles. Here in place of eagles we see ram's heads.

Here in place of eagles we see ram's heads. Another example of "wind-blown" acanthus on a column of white proconnessian marble.

Another example of "wind-blown" acanthus on a column of white proconnessian marble. All of these capitals are carved in white proconnesian marble.

All of these capitals are carved in white proconnesian marble. This battered capital was found on the grounds of the Mangana Palace and Church of Saint George of the Mangana. It's now in the Istanbul Museum.

This battered capital was found on the grounds of the Mangana Palace and Church of Saint George of the Mangana. It's now in the Istanbul Museum. A basket capital.

A basket capital. This capital originally had a peacock in the center which has broken off. It is on the exterior of a Byzantine building in Thessaloniki.

This capital originally had a peacock in the center which has broken off. It is on the exterior of a Byzantine building in Thessaloniki. This is a beautiful lace capital with grape vines, grapes and birds eating them. The top of the capital is wrapped with the body of a snake. It is now in the Istanbul Museum. Perhaps this is the most beautiful capital that has survived from Constantinople.

This is a beautiful lace capital with grape vines, grapes and birds eating them. The top of the capital is wrapped with the body of a snake. It is now in the Istanbul Museum. Perhaps this is the most beautiful capital that has survived from Constantinople. A beautiful Theodosian capital from Thessaloniki.

A beautiful Theodosian capital from Thessaloniki. A wonderful "Green Man" capital in the Istanbul Museum. Green Men can be seen in the floor mosaics of the Great Palace.

A wonderful "Green Man" capital in the Istanbul Museum. Green Men can be seen in the floor mosaics of the Great Palace. An ionic impost capital with a peacock.

An ionic impost capital with a peacock.

Above is a map of the quarries. In the eastern desert of Egypt are located about 45 km west of Hurghada the Mons Porphyrites quarries where our columns originated. The Roman legionnaire Gaius Comenius Leugas discovered the red porphyritic rock in 18 AD in the stony, rugged and towering mountains of Wadi Abu Ma'amel, an extremely dry desert. I have no idea how or why he found it. The quarries where worked by slaves in horrible conditions. Thousands of them must have died making columns like this. There was no water o food, everything had to be brought in. The hard stone dulled the metal tools used to work it and they had to be constantly resharpened. It must have been seasonal work - I cannot imagine the work continuing in the summer when the temperature is as high as 40 C. Below is an image of the site:

Above is a map of the quarries. In the eastern desert of Egypt are located about 45 km west of Hurghada the Mons Porphyrites quarries where our columns originated. The Roman legionnaire Gaius Comenius Leugas discovered the red porphyritic rock in 18 AD in the stony, rugged and towering mountains of Wadi Abu Ma'amel, an extremely dry desert. I have no idea how or why he found it. The quarries where worked by slaves in horrible conditions. Thousands of them must have died making columns like this. There was no water o food, everything had to be brought in. The hard stone dulled the metal tools used to work it and they had to be constantly resharpened. It must have been seasonal work - I cannot imagine the work continuing in the summer when the temperature is as high as 40 C. Below is an image of the site:

There were a number of huge porphyry columns in Constantinople, including the great Pillar of Constantine in the center of his circular forum.

There were a number of huge porphyry columns in Constantinople, including the great Pillar of Constantine in the center of his circular forum.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints