The rare and exotic marble revetment of the church - which was assembled from all over the Roman world - was considered the greatest glory of its original decoration. In covering the walls of the church with it Justinian was following in the long tradition of Roman Imperial gifts of prestige colored marbles. The Roman Emperor Hadrian gave colored marble columns to his favorite cities, like Athens, which received 100 columns in Phrygian marble for a temple of Hera and Zeus from him. Hadrian had toured extensively throughout the empire and had probably visited many of the quarries. It is believed that Hadrian made the quarries of Verde Antico and the violet-colored Troad granite state-owned enterprises in the second century. He also made extensive gifts of green-veined cippolino verde marble for the embellishment of public buildings, like baths.

The rare and exotic marble revetment of the church - which was assembled from all over the Roman world - was considered the greatest glory of its original decoration. In covering the walls of the church with it Justinian was following in the long tradition of Roman Imperial gifts of prestige colored marbles. The Roman Emperor Hadrian gave colored marble columns to his favorite cities, like Athens, which received 100 columns in Phrygian marble for a temple of Hera and Zeus from him. Hadrian had toured extensively throughout the empire and had probably visited many of the quarries. It is believed that Hadrian made the quarries of Verde Antico and the violet-colored Troad granite state-owned enterprises in the second century. He also made extensive gifts of green-veined cippolino verde marble for the embellishment of public buildings, like baths.

When construction on Hagia Sophia was in the planning stage the project managers and contractors had to assess how much marble they would need for the project based on the plans for the church. This was fairly easy to do since it was simply a matter of wall acreage. Then the next assessment would have been of the colored stone that might be already in-stock in Constantinople marble yards. It must have been obvious from this point that the vast size of the church would exhaust existing stores and require new stone.

Justinian's Imperial bureaucracy - primarily organized to levy and collect taxes - could quickly inventory what stone was in the provinces from known sources, the difficulty of obtaining it and the cost. They would have reported what had already been quarried - lying around in "ready-to-go" blocks and determining what would need to be ordered new. Some of the quarries had large numbers of roughed-out marble blocks and columns lying around in the 6th century. New quarrying would be ordered where needed. Marble could be delivered in blocks or slabs based on the cost and difficulty of transport. Imperial marble hunters were especially on the lookout for any stray blocks or columns of Red Porphyry.

In order to save time local authorities and quarry operators would have been given orders for the most desirable marbles immediately. Many of the quarries were state-owned and operated which was a cost factor. Shipping was also a critical factor; fortunately there were many sources for beautiful marbles that were along the shores of the Aegean Sea and in nearby places like Bithynia and western Asia Minor. The agents were also looking for marbles with dramatic colors and patterns. There are lots of book-matched black and white breccia panels from France in the nave. These blocks must have already been in Constantinople, since transport from the high mountain quarries of the Pyrénées would have been next to impossible to deliver in the 6th century.

The revetment decoration of Hagia Sophia was planned for each section of the church, starting withe the apse, then the nave, followed by the ground floor aisles, then the narthexes and finally the upper galleries. One can see certain marbles - like Giallo Antico - a pale yellow color - being used in the narthex in broad borders next to green Verde Antico - only here in this space. There could be many reasons for it being used there specifically, perhaps it was because this spot - the entry into the nave was extra important, or perhaps it was the light there. There may not have been enough Giallo Antico to use elsewhere; it came from an unstable province - North Africa - Tunisia - and probably was being supplied from existing stock, rather than being quarried for the job. In the Roman Empire Giallo Antico was commonly used in large architectural elements and some of the revetment in Hagia Sophia was reused.

The marble blocks were assembled on the building site, sawed into panels, polished and then mounted onto the walls with clamps and mortar. Every stone was different and had factors that had an effect on its final form. Some stones were harder than others to cut while others were more difficult to polish. For example, Verde Antique is composed of elements that are both hard and soft; when you polish it it comes out somewhat lumpy. The builders had to wait until the stone and brickwork were fully dry before mounting the revetment. Even though it's a marble veneer mounted on a flat surface some stones were better suited for the job than others. Some stones - like Verde Antico - were compact and reliable, while others, like onyx, were subject to fracturing and flaking.

I have l ready mentioned that the decorators of Hagia Sophia planned the placement of stones for their color and how they reflected light. They placed certain colors next to each other for their effect on each other. They choose others based on how dramatic their veining was. Some stones, like onyx, are translucent - like gold mosaic - and absorb and both reflect light. Placing them next to a flat breccia like white and black Celticum creates an interesting contrast of surfaces in a bright interior like Hagia Sophia. One can actually watch how light moves across the walls of the nave and see many interesting effects on the surfaces of different stones.

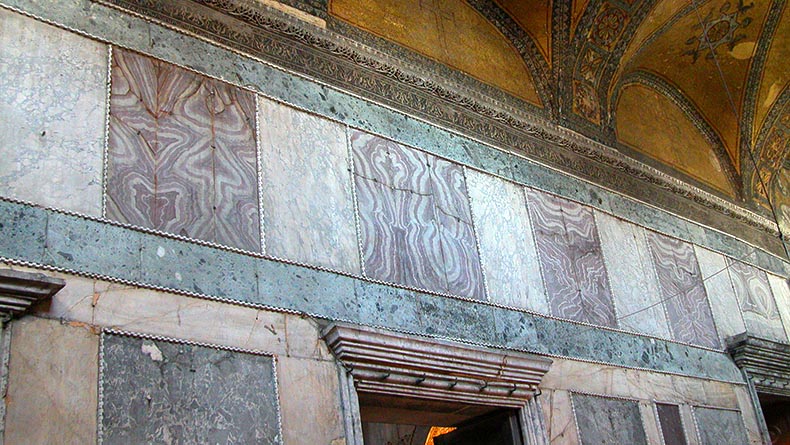

Concerning the marble revetment in the church we can find the green marble of Karystos, rose-colored from Phrygia, red Imperial Porphyry from Egypt, Green Porphyry from Sparta, buff lassikos from Caria, white-yellowish marble from Lydia, gold-colored marble from Libya, chunky black and white breccia Celticum from France, honey-colored onyx from Pamukkale, green Verde Antique from Thessaly, white marble from Proconnesos and the grey-colored marble from Vosporos, which have all been used. The position of each piece was carefully selected to create patterns and color harmonies. Some sections of revetment have patterns that resemble hanging curtains and others resemble human faces and angels. The mosaics in the arches and vaults were color-keyed to enhance the revetment near it. The huge golden bands of onyx would have echoed the mosaics above.

About the revetment of the church Paul the Silentiary wrote in 563:

"Upon the carved stone wall curious designs glitter everywhere. These have been produced by the quarries of sea-girt Proconnesus. The joining of the cut marbles resembles the art of painting for you may see the veins of the square and octagonal stones meeting so as to form devices: connected in this way, the stones imitate the glories of painting. And outside the divine church you may see everywhere, along its flanks and boundaries, many open courts. These have been fashioned with cunning skill about the holy building that it may appear bathed all round by the bright light of day. Yet who, even in the thundering strains of Homer, shall sing the marble meadows gathered upon the mighty walls and spreading pavement of the lofty church? Mining [tools of] toothed steel have cut these from the green flanks of Carystus and have cleft the speckled Phrygian stone, sometimes rosy mixed with white, sometimes gleaming with purple and silver flowers. There is a wealth of porphyry stone, too, besprinkled with little bright stars that had laden the river-boat on the broad Nile. You may see the bright green stone of Laconia and the glittering marble with wavy veins found in the deep gullies of the Iasian peaks, exhibiting slanting streaks of blood-red and livid white; the pale yellow with swirling red from the Lydian headland; the glittering crocus-like golden stone which the Libyan sun, warming it with its golden light, has produced on the steep flanks of the Moorish hills; that of glittering black upon which the Celtic crags, deep in ice, have poured here and there an abundance of milk; the pale onyx with glint of precious metal; and that which the land of Atrax yields, not from some upland glen, but from the level plain: in parts vivid green not unlike emerald, in others of a darker green, almost blue. It has spots resembling snow next to flashes of black so that in one stone various beauties mingle."

The revetment has been laid in broad horizontal layers of contrasting colors and patterns, like the striking red cippolino rosso. The contrast with the oceans of plain gold mosaic in the vaults can no longer be appreciated.

Over the centuries, some parts of the revetment have degraded and have lost their color. For example some of the panels of Verde Antique (see above) have lost their color, turning gray, and have degraded, in parts, to talc (this has also happened to some of columns of Verde Antique). Due to the physical stress the church has constantly been under since its construction, revetment panels have cracked all over Hagia Sophia and some have become fragmented or fallen down, even in the nave. Panels have been moved from the aisles and galleries to replace these. As a result a significant part of the revetment has been lost in the aisles and has been replaced with painted plaster. It would be easy to replace the missing slabs, many of the quarries can still be worked or are operating today. The Fossatis speculated that the revetment in the aisles and galleries was lost during a botched restoration in 1815.

You would probably be surprised to know that the large parts of the revetment have their original surfaces and have not been cleaned and polished in more than 1,000 years! You can still find the undisturbed history of the church in the layers of oil, grime and candle soot there.

The Byzantine Institute began to polish and clean the revetment starting with the western nave wall in 1958, but the work stopped. Continuing the polishing would remove the gray dusty blanket that covers the revetment and bring out the colors and contrasts that are missing today. One can single out the change that would occur in the appearance of the now dingy-gray looking black and white Celtic marble from France that would shine like a mirror if it was cleaned as an example.

The Red Porphyry panels in Hagia Sophia were considered the most rare and valuable. A lot of it was used in the sanctuary. Although it looks solid red it actually can have inclusions, white crystals, like snowflakes. Red Porphyry, porfido rosso antico, comes from Gebel Dokhan, in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Because of its purple color it was associated with the Imperial family. It was cut very thinly and some of the panels were pieced together so that the seams were invisible. Red Porphyry is very hard, but brittle. The precarious state of the Red Porphyry columns of Hagia Sophia and their reinforcement with bronze-plated iron rings shows the danger of believing that hardness equals structural strength. Porfido rosso antico is incredibly difficult to carve or cut and has to be sawed or modeled by grinding, which can takes a long time. It results in its own "style" of sculpture which is difficult to mold into classical shapes and figures. In the late third and forth centuries this rather barbaric style came into its own during the brutal, militaristic days of Diocletian and the Tetrarchy. The quarrying of this stone stopped in the fifth century. The panels are surrounded with marble inlaid panels of urns, acanthus and crosses. It is remarkable that these have survived since most of the crosses in Hagia Sophia were destroyed or covered over. They must have been so beautiful that even the Muslim Ottomans were too ashamed to destroy them. You will notice that the porphyry panels are different sizes. The porphyry was treated like a semi-precious jewel and the borders its setting. The Romans treated rare revetments in a similar fashion.

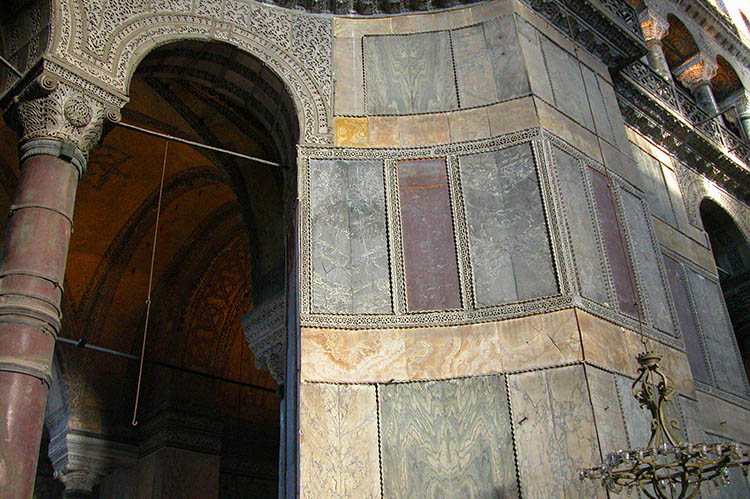

In this image were have backed to show the position of the panels on the wall of the nave of Hagia Sophia. The great green panels are made of Verde Antique marble from Thessaly in Greece. During the reign of Justinian these quarries were a reliable source because of their management from the nearby fortified citadel of Kerkinion Kastri in the Valley of Larissa. Hagia Sophia is full of enormous columns in this stone. The Verde Antique panels in Hagia Sophia used to have an intense green color, but have turned gray through a chemical transformation that is turning them into talc. You can also see this happening to Verde Antique panels in the Chora Church. Verde Antique is a "noble" serpentine stone and is greasy to the touch. In the lower right, near the door you can see a marble panel has been replaced and is mismatched. It looks like the white marble panels here have been reset. You can also see there has been damage to the floor in front of the panels. There must have been some Christian installation here that the Turks have removed.

Here is a huge wall in Hagia Sophia showing marble revetment.

Here is a close-up of the great, book-matched double panel of cippolino rosso in the center. Cipollino rosso, also called Carian or Iasos marble, comes from Kiyi Kislacik in Mugla province, Turkey and is mined today. This would be a very bright and striking panel if it were polished.

Other rosy red panels are made of a breccia marble from Lydia.

Here is carved low relief panel in Green Porphyry. A number of these have been set into the revetment of Hagia Sophia. Green Porphyry, called Porfido serpentino antico or porfido verde agatata, comes from Krokees, Laconia, in the Peloponnese, Greece, which is near Sparta. Green Porphyry was considered the second most valuable marble used in Hagia Sophia. The relief design has lifted and fallen away in numerous places and has been replaced with painted plaster, which is now discolored. These panels are really filthy and in bad condition. Green Porphyry is a beautiful stone that looks like jade. It usually comes in small blocks, these six foot tall panels are unique for their size.

The large panels with black and red veining are Dokimeion Pavonazzetto marble, from Iscehisar (Synnada), in Afyonkarahisar province, Turkey. The Dokimeion quarries were under Imperial control so it is no surprise that large quantities and a variety of colors and veining patterns of this fine polychrome marble were used in Hagia Sophia. The surface transport of Dokimeion marble to the coast was expensive, so it always was a luxury material. There was still some quarrying of this stone in the tenth and eleventh centuries. The beautiful columns supporting the nineteenth century Sultan's Box in Hagia Sophia are Dokimeion Pavonazzetto marble.

The panels with black and white masses are Celticum marble, "petit antique", from area around St. Girons Hèche and Hèchettes, in Hautes-Pyrénées, France. They are also called "bianco e nero antico". This was the only Western European marble known to be used as revetment in Constantinople. It is a breccia of black and grey limestone clasts in a compact white granular calcite matrix. The production of this marble in France stopped by the sixth century.

The black panel in the lower right is a nineteenth century painted plaster replacement for a missing one in green-gray cippolino - which means onion - marble. "Marmor carystium" - which looks like it has many layers that could peel off like an onion - was quarried in several locations on the south-west coast of the Greek island of Euboea and is a folded medium-grained calcite marble with layers rich in green iron-bearing silicate minerals including chlorite and epidote. The heavily pattered variety was quarried on the slopes of Mount Okhi and the ancient quarries can still be seen today. There are many panels of it in Hagia Sophia, which are usually book-matched with wild ghostly figures like birds, angels and monstrous faces in the veining. The Romans really liked this marble and used it a lot in Trajan's Forum, not only for architectural elements like columns, but also for sculpture (check out the monolithic Dacian captives now on the Arch of Constantine for examples). There was probably a lot of this stone lying around the marble yards in the sixth century.

Here are more panels in red-veined Pavonazzetto marble, a center double-matched panel in green cippolino and some huge bands of golden onyx, which are Alabastro fiorito, from the Pamukkale area in Denizli, Turkey. This onyx is actually a banded travertine. Pamukkale is the site of the ancient city of Hierapolis, and travertine, deposited by hot springs, forms huge terraces from which stone was extracted in ancient times, and is still quarried to this day. Ancient quarries have been located near the ruins of Hierapolis and near the village of Gölemezli. Recently it has been noted by experts that the variety of the veining and color of the onyx in the church means that some might be Egyptian alabaster or have come from other sources in Asia Minor, not just Pamukkale. Paul the Silentiary only describes the onyx used in the ambo as being from Hierapolis. Perhaps even he wasn't sure where the onyx came from. One complicating factor is that the Fossatis used new sources for some of their repairs. Recent research has also pointed out that some of the sixth century onyx panels in the church are reused.

As mentioned earlier the pale yellow marble revetments are either plain giallo antico, or when they have red veining, giallo antico brecciato, both from Tunisia. Other yellow marble revetment found in Hagia Sophia is Italian "giallo d' Siena" and these must be more nineteenth century repairs.

These bands are around 6 feet tall. Originally they were set in matched wavy patterns. Much resetting has taken place. They fracture easily and there are some losses. The bands are set apart by white marble carved framing. The background of the carved marble bands was painted royal blue while the marble was gilded. All of this needs a cleaning.

The golden bands of onyx with Red Porphyry panels nearby, adds to the overall richness of the decoration of Hagia Sophia that has so impressed visitors to the church over the centuries.

The Red Porphyry panels are the same width as the Porphyry columns in the semi-circular exhedra. The panels were probably cut from columns. You can see here how the flat panels were used on curved surfaces.

Here is a picture of the left wall in the West Gallery. The white marble in the center is Proconnesian marble, marmo di Proconneso, from the island of Marmara, which is 100 miles from Constantinople. It is a coarse-grained calcite marble with grey graphite-bearing banding. Especially fine examples of Proconnesian revetment like this can have a crystalline structure that adds a deep soft flash to the stone. This marble is found throughout Hagia Sophia and has been used as revetment, flooring, columns and carved architectural elements. The Proconnesian quarries were under Imperial administration. This marble was extensively used all over the late Roman Empire as semi-finished and fully carved elements. Production seems to have stopped in theseventh century. At the top is a frieze of cipollino rosso. Below the Proconnesian is a band of Pavonazzetto marble, and below that a broad-banded base pal also in Proconnesian. You will notice that thee panels have been reset. The third and forth panels in the broad center band are upside down.

Another wall from the galleries showing a broad-banded set of Proconnesian book-matched panels. You can see the marks were the panels are attached to the wall with iron clamps. The second panel from the left has the remains of a hook in its center. Below it is a band of red-veined Pavonazzetto marble and rosy breccia, which has been messed around with and has been patched. Below that is another broad-lined band of Proconnesian marble.

This is from the right wall of the West Gallery. The Procconesian marble revetment is book-matched and heavily figured. The Byzantines saw figures in the revetment patterns. Here we can see winged angels. Near the bottom is a row of 5 crosses, which were inlaid into the stone and removed by the Turks. These crosses are in the direction of the South Gallery and would have been venerated by pilgrims and worshipers headed to the location of the Deesis. Below them is a band of Pavonazzetto marble. The crosses are at 'kissing' level which gives you an idea of the scale. Above is a close-up of the cross on the far left. The cross is larger than your hand. These crosses were set into the bases of columns and are inset into walls. The crosses on column bases are all on the ground floor of the church and are placed only on the bases of porphyry columns in the exhedra facing east. The cases of the columns are higher than other bases in the nave and could be kissed. The porphyry columns of Hagia Sophia were always singled out for special attention by pilgrims. Those in the northwest bay were thought to be the location of miraculous cures. There is another cross inserted into the revetment of the nave closest to altar, just to left of the curve of the porphyry columns. Relics were attached to all of the columns of Hagia Sophia above their capitals. All of the crosses inserted into the walls are at the same height so they could be kissed by the faithful, around 55 inches. Two of the crosses are in the north part of the narthex between the doors marking the spot where pilgrims entered the nave of Hagia Sophia. You can look for these in the green band of marble, the third one from the floor. Pilgrims would kiss these crosses before entering. We don't know the date of any of the crosses, but they must all be post-iconoclasm.

Above is a close-up of the cross on the far left. The cross is larger than your hand. These crosses were set into the bases of columns and are inset into walls. The crosses on column bases are all on the ground floor of the church and are placed only on the bases of porphyry columns in the exhedra facing east. The cases of the columns are higher than other bases in the nave and could be kissed. The porphyry columns of Hagia Sophia were always singled out for special attention by pilgrims. Those in the northwest bay were thought to be the location of miraculous cures. There is another cross inserted into the revetment of the nave closest to altar, just to left of the curve of the porphyry columns. Relics were attached to all of the columns of Hagia Sophia above their capitals. All of the crosses inserted into the walls are at the same height so they could be kissed by the faithful, around 55 inches. Two of the crosses are in the north part of the narthex between the doors marking the spot where pilgrims entered the nave of Hagia Sophia. You can look for these in the green band of marble, the third one from the floor. Pilgrims would kiss these crosses before entering. We don't know the date of any of the crosses, but they must all be post-iconoclasm.

Above is an example of ancient graffiti scratched into the revetment of Haghia Sophia. There are thousands of these, most of which cannot be seen. Is that a face in the center?

Above is a set of revetment below the mosaic of the Emperor Alexander. At the top is a band of red cippoliono, below that a set of cool Procconesian book-matched panels. Look in the pattern and you can see a number of bearded faces. Below is a row of red-veined Pavonazzetto and rosy breccia, along with other miss-matched marbles, which means they have been reset.

A close-up of the pattern so you can see the faces better. The holes mark the position of iron claps, which have been pried out.

Here are a couple of pictures of revetment in the narthex below. Those big gray (they are really black) and white panels need cleaning and polishing - they are more of Celticum marble from St. Girons Hèche and Hèchettes, in Hautes-Pyrénées, France. The broad framing bands are pale yellow giallo antico, which was used in the narthex instead of golden onyx.

Here is a view of some of the splendid carved and inlaid marble paneling in the apse of Hagia Sophia. The light flat and raised bands are in yellow Phrygian marble, which are set with rich, Red Porphyry bands, the large center panel is also Red Porphyry (the top fourth is missing. At the very top is a wonderful inlaid band with urns and red porphyry discs in opus sectile which has been set in pitch. These panels are huge, six feet or more in height. The walls of the apse hve the richest revetment ornament in the entire church.

Here's a close-up.

This panel comes from the western wall of he nave above the Royal Doors. At the top left and in the lower right are two panels of green Verde Antique. The walls here were cleaned and restored in 1958 by the Byzantine Institute. The bottom panel of Verde Antique has been moved there to replace a life-sized mosaic icon of Christ Chalkis that was here when Hagia Sophia was a church. The bodies of the dolphins are of Green Porphyry with Red Porphyry used in the curving parts of the bodies near the tails, but, whereas the thin lines that delineate the bodies and tails in the left panel are made of very narrow pieces of white (dolomite?) rock, most of the equivalent lines in the dolphins of the right panel are executed in nacre (mother-of-pearl). In the latter panel nacre is also used in the outlining of the eyes, the small circular dots grouped around the eyes, the main body of the bands that bind the tails of the fish, and in the diagonal pieces in the shafts of the tridents that indicate their spiral treatment. Whereas very little red (porphyry) is used in the fins marking the gills of the four fish in the right-hand panel, the treatment of the eyes and fins of the left-hand panel is more colorful. Here, the areas surrounding the eyes are inlaid with bright green, the centers of the eyes are bright red, almost vermillion, and the fins behind the eyes are of darker red. The jewels in the bands with which the tails of the fish are bound are variously disposed stones of red and green.

This is the most ornate marble panel in the revetment of Hagia Sophia. In the center at the top, immediately below the cornice, is a panel which represents an aedicula surmounted by a dome-like canopy. Like most of the marble slabs that compose the revetments of the church, this panel was framed by a projecting double billet molding of Proconnesian marble. Within this is the outer border made up of short lengths of a red stone. This red border is set with its narrow edge flush with the surface of the panel, and because of its great depth, which nearly equals the total thickness of the panel, it forms the outer frame of the panel itself. All other pieces of surface stone that make up the design within this outer frame are very thin and are set into a very hard adhesive bedding of a thick and of a brown color, which is made of a compound of a resin, or pitch, and what is believed to be marble dust. This bedding is backed by pieces of slate. The canopy is indicated as a kind of ribbed dome by means of eight strips of white stone that curve upward to converge at the top, and by two shorter curved strips in the center.

Above the latter is a small equal-armed cross whose arms are formed of isosceles triangles. Within narrow borders at the sides of the canopy stand two birds which face inward toward one another.

Below the cornice two parted curtains, each supported by three rings on a curtain rod, hang suspended between the two Ionic columns at the back. The curtains are knotted in the center and are fringed at the bottom. In the space between the curtains is a large jeweled cross which stands on a trapezoidal base composed of four horizontal bands of dark gray marble separated from one another by narrower bands of white stone. The sides of the base are also outlined in white stone. The cross has flaring arms with serifs at the corners in the form of teardrops. At the center was a large square gem. Each of the two vertical arms had one rectangular and one ovoid gem as well as six small circular ones, while the lateral arms had single rectangular gems surrounded by four small circular ones. Suspended from the two side arms were six pearls. In the course of its cleaning and repair it became evident that efforts had been made to disguise the existence of the crosses and the two birds, which were removed.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints