Ikon History - Golden Age of Russian Ikons

During the late 12th and early 13th centuries Russia was racked by internal divisions. Petty local princes fought for political supremacy and destroyed the economic strength and unity of the nation. Outside forces were eager to exploit these divisions and in 1237 the worst possible calumnity befell Russia when the Mongol Khan and his Muslim army fell on Russia like ravenous wolves. It was a very unlucky time for the Russia. On December 6, 1240 the great city of Kiev fell to the Muslim Mongols. After a ferocious siege of the city the defences suddenly were breached. Thousands of Muslim soldiers poured into the Kiev hungry for loot, rape and destruction. Ignoring the sanctity of shrines of Kiev, the churches and cathedrals of the city were set aflame by the Mongols with full knowledge that the people of the city - innocent men, women and children - were huddled within, praying for deliverance. Meanwhile, tens of thousands perished in their homes and the streets of the city, cut down indiscriminately by the Mongols. It was the blackest moment in the history of ancient Russ.

For sixty years the Mongols continuously pillaged the country at leisure. After they had carried off everything of value they could get their hands on, the Mongols of the Golden Horde settled down in their domination of Russia. They began a program of extortion, exacting ruinous yearly tribute from the population. During the period of Mongol occupation all of the arts, including ikon painting suffered. The Mongols bled the country dry, but they were prepared to leave the population alone as long as their heavy taxes were collected and delivered to them by their Russian vassals. Lucky for Russia the Mongol forces were unable to subjugate the entire country. In the north the famous merchant city of Novgorod the Great maintained its independence in the face of the Mongol hordes from the east and the Teutonic Knights pressing from the Baltic. In Novgorod and in the nearby city of Pskov, Russian culture went on in uncertain and perilous times. In both cities local schools with unique characteristics in ikon painting emerged. Very little of the artistic output of this period has survived, but remaining examples tell us the deep well of classicism, which had flowed from Byzantium into Russia had been cut off by the Mongol conquest. Novgorod and Pskov ikons of this period are often harsh and austere. Bright red backgrounds become commonplace, outlines become simpler, and the modeling of figures is noticeably flat and abstract. The overall effect of ikons of this period is direct and no-nonsense.

This period also saw the rise of the Muscovite state where a new center of ikon painting emerged. The new Moscow style of ikon painting was heavily influenced by foreign Greek and Serbian artists who were imported by the relatively wealthy Moscow Princes to paint the new churches of their city. In 1378 Theophanes, a Greek artist, painted the church of the Transfiguration in Moscow. His work in Russia was greeted with astonishment by local artists. Theophanes worked very fast and his style was extremely expressive and mystical. He could draw a large figure in fresco on a wall with guide books or drafts, a bravura performance which dumfounded the Russia artists, who had been trained to careful copy from pattern books. Local artists tried to imitate his style, but their work shows how difficult it was to master his free and easy-flowing style.

During the period from 1350 through the fall of Constantinople in 1453 contacts between Byzantium and Russia again became frequent. Churchmen, merchants and artists from Russia were able to see, first-hand, the splendors and ancient Christian art of the city. Many ikons of in the distinctive Paleologian style were imported to Russia. These had a tremendous influence on taste and painting styles.

The Royal Doors at upper left date from around 1425 and show how deeply the Paleologian style permeated Russian art of the time. "Royal Doors" lead from the center of the church through a screen of ikons into the altar area. They are a primary focus of the liturgy in Orthodox churches. At the top of the doors is the familiar scene of the Annunciation shown in two parts. Below are ikons of the four Evangelists. All the figures show the small head, tiny feet, hands, swelling bodies and fantastic architecture that are the signature of the Paleologian style. However much they follow Byzantine models, the Royal Doors are completely Russian in feeling, color and rhythm. The Russian palate was different from the Byzantine. In Russia some pigments - such as bright blues - were difficult to locate and very expensive. They were reserved for paintings of Christ of the Theotokos. Use of local materials leans the Russian palate of the time toward bright cinnabars, golden ochres and dark greens. There is also a noticeable tendency toward wide expanses of pure color without dark underpainting.

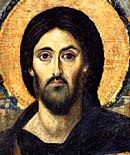

The third ikon at left shows Christ in Glory and dates from around 1410 and is the work of the great Andrei Rublev, a monastic painter who has been recognized as a saint by the Russian church. The ikon shows Christ enthroned on a heavenly throne. In the blue halo around Him fly angelic cherubim. In the red corners are symbols of the four Evangelists. The small ikon is of extraordinary quality and deeply spiritual. The technique and drawing are superb. Many of Rublev's ikons have been damaged by repainting and excessive restoration. This is one of the few examples which retains its surface and hence shows us the original appearance of Rublev's masterful work.

The next ikon at left is called the "Trinity" and it originally adorned the ikonstasis of the church in the holy St. Sergius Monastery near Moscow where the body of the St. Sergius lay in a silver coffin. The ikon has been heavily damaged by the attachment of a heavy silver cover, repainting and overzealous restoration in the Soviet Era. The paint surfaces are heavily abraded and it is difficult to appreciate the original state of the ikon today. masterful drawing, intense spiritualism and love of the classical beauty of old Byzantium still shines through. It was painted in 1411 and shows the three angels who visited Abraham at Mamre and are symbols of the Holy Trinity. In the center is the angel representing Christ. This is evident from the purple and blue garments. To the right is the angel who represents the Holy Spirit. Both angels bow before the third, who represents God the Father and the senior member of the Trinity. The ikon at bottom is a much reduced copy of the Trinity dating from the late 1400's. The technique does not compare to Rublev, but the colors give some hint of the intensity of the hues in the Trinity when it was first painted.

Next chapter: Twilight of Byzantium